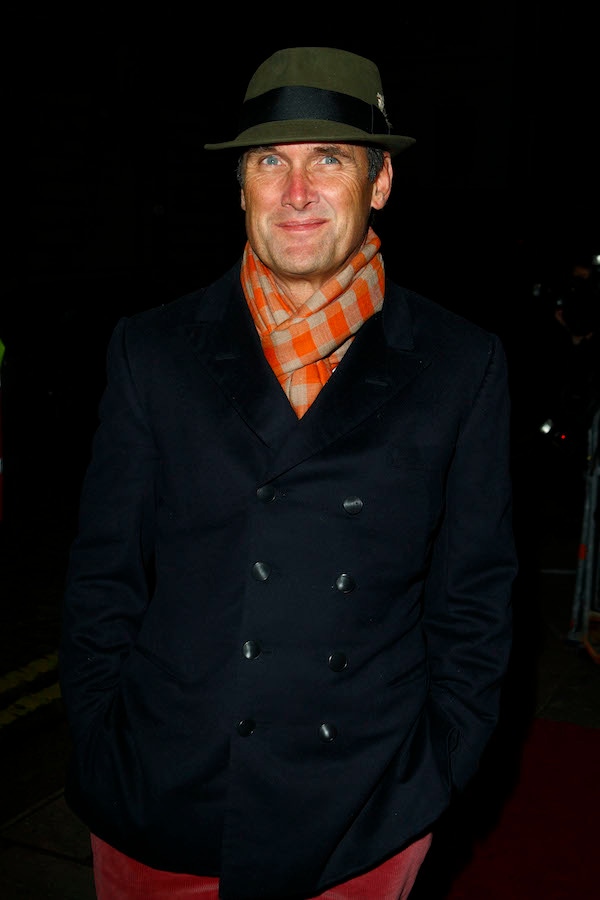

The Most Raffish Belletrist on Fleet Street: AA Gill

The Rake laments the loss of one of the most influential, acerbic and undeniably elegant journalists of modern times.

AA Gill’s writing style, like Nabokov’s or Martin Amis’s, was almost annoyingly brilliant: decadent, rhythmic, luminous, omniscient, throwaway, flowery, floury, gamey sentences and metaphors to roll around the mouth. The dyslexic dictations of an ex-stutterer were shaped into polychromatic perfection: Vanity Fair, for whom he wrote as a contributing editor, called him “a circus master with a comma for a whip”. But his use of language was immediately evocative and definitively original: it demystified rather than obscured, far from the imitation-Gill chintz of a disciple like me. He contested in an interview with BBC Storyville’s Nick Fraser that the main function of a critic was to "sell newspapers" and he was the kind of columnist, perhaps the only columnist, who wrote so well you would buy the whole newspaper just to read him.

The Sunday Times TV and food critic, who died of lung cancer on Saturday at the age of 62, could write about anything and had a particularly astute sense of place. His prose flew across the Atlantic in both directions, here an article on London for The New York Times, there a book To America With Love. A sample from the latter: “Where politer European cities might have had street mimes, New York has always had the Brechtian street theatre of pavement psychodrama: the muttering, bellowing, gesticulating and teetering looney tunes for whom the drugs are no longer working, who look like characters from Exodus, prophets of urban collapse and carnal comeuppance.” He wrote, incomparably, about war, parenthood, phone etiquette and even football: after the Champions League Final in 2011, he compared the playing styles of Manchester United and Barcelona to the art and architecture of their cities, Gaudíly-elusive tiki-taka against the ecstatic, redbrick New Order.

"He was the kind of columnist who wrote so well you would buy the whole newspaper just to read him."He could expand or distil, a double master of one-liners and prose-poetry. Lucian Freud looked like a “buzzard who’d eaten the cook”. New York was a “divorcee looking for a richer second country”. The beauty of his final piece, for Gourmet Traveller, surpasses Cawdor’s, the Scottish village from which he wrote it: “the rowan are red, like blood-splatters against leaves of tannin-yellow. It all smells of corruption here, tilth and fungus…. It's a place I love as dearly as I can love the blood-bitter peat, the mushrooms and mud and the bath-salts of wet dog.” His private life was full of contradictions. The son of Civilisation director Michael Gill and actress Yvonne Gilan (who played the flirty Madame Peignoir in Fawlty Towers), he saw himself as Scottish though his voice suggested otherwise (in Gill’s own words, he sounded like “Bertie Wooster’s homosexual friend”). He was married three times, to writer Cressida Connolly, now-Home Secretary Amber Rudd and South African model-turned-Tatler journalist Nicola Formby. A lifelong Labour voter, he lived in Chipping Norton near Jeremy Clarkson and Rebekah Brooks, both close friends. He originally trained as a visual artist at the Slade, but discovered his real calling in his thirties when Tatler asked him to write about art. His first piece moved his editor to tears, he was poached by the Sunday Times and he soon became their highest-paid columnist. According to a Sunday Times piece over the weekend, when the legendary tailor Doug Hayward started to make his suits, Gill insisted they were lined with women’s silk scarves from Hermès.

Before he became the most raffish belletrist on Fleet Street, Gill spent fifteen years wetting himself, getting into fights and drinking Benilyn through a straw. Pour Me, the memoir of the alcoholism that imbued his twenties and made him a world-class observer from an outsider’s perspective, is mordantly funny and free of self-pity. On April Fool’s Day 1984, at the age of 30, he drank two bottles of vintage champagne with his father on a train to a rehab clinic in Wiltshire and never drank again.

After Alcoholics Anonymous, Adrian Anthony became AA and food usurped drink. Jeremy Clarkson claims he was the only man who had pudding with breakfast, followed by cheese. Lynn Barber lists a few of his culinary hates as dinner parties (“the work of the devil”), balsamic vinegar, gastro-pubs (“Food and pubs go together like frogs and lawnmowers”), fat people, Christmas dinner, Greek food, Tex-Mex, Starbucks, warm salads, winkles, seasonal eating, organic food (“trying to make people feel guilty for buying cheap chickens”) and vegetarians. His wisdom had a concise Voltairean mischief. Chefs become chefs because “they’re not allowed into rooms with windows”. Pasta is eaten by “happy, smiley people having fun with people they love or fancy and are about to shag,” whereas “noodles are eaten by people who have no friends”. The most a Wiener schnitzel can hope for is “utter indifference”. But he praised with relish. One lobster bisque was as “silky as a gigolo’s compliment and fishy as a chancellor’s promise”. He loved Riva in Barnes, The Wolseley on Piccadilly and Whitby’s Magpie Café, his recent review of which revealed his cancer and lauded “without pretension but with utter self-confidence… the best fish and chips in the world”.

"The outrageous ease of his columns made so many people want to write."Everyone knows what he said about the Welsh, Clare Balding, Mary Beard and the time he shot a baboon. He also had a pop at golf, Louis Theroux, Michael Portillo. Morrissey, Doctor Who, Belgians, PRs (“the headlice of civilisation”) and Celine Dion (“a corny, calculated act for clueless, obese fans”). Some might question the moral authority of the professional provocateur, peerlessly well paid to be controversial to a deadline with the power to put a restaurant out of business with a single simile, or wince at his pomposity or his obsession with looks. But he had a disarming gift for empathy. Writer Jonathan Meades said he was “promiscuously interested in just about anything save himself”. Gill’s piece on Brexit and the “debilitating Little English drug” of nostalgia was, predictably, the most incisive take on the subject. Essays on refugees compress well-versed anger into vivid Swiftian imagery, like the Hungarians who spray water cannon and teargas at migrants through the wire “like demented cleaning ladies trying to remove stubborn stains”. He adored fatherhood, embraced the “lightning on a dark night” of Christianity and praised television as “the greatest thing of my life and the greatest cultural invention of the last 500 years”. And then there’s his astounding final Sunday Times article on the NHS, the cure that might have saved him and his gratitude he’s made it this far. “All appetite is a remembrance, the déjà vu of our mouths”, he wrote in his last ever piece. In this grimmest of years for famous losses, he was the most explicit influence on young writers. The outrageous ease of his columns made so many people want to write, an unforgettable English teacher who made you feel cleverer. AA Gill was writing as fine dining, a banquet every Sunday, iron butter in the sea jaws of the mind. Of all his aphorisms printed in the last few days, my favourite was this characteristic mix of taste, humour and refined feeling: “Kindness, like comedy, is all in the timing”.