I've Got Sole But I'm Not a Soldier

Bespoke shoemaking is not for the faint of heart. But, as The Rake's Editor, Tom Chamberlin, discovered when he collaborated with G.J. Cleverley, the journey is worth it — and the piece of art you hold in your hands will become a bridge between generations.

A love affair with shoes is not just for women — let’s get that out of the way. And men, not women, are to blame for the existence of the stereotype. For decades we have poked fun at our partners’ fascination for footwear, refusing to employ any nuance in understanding the bridge between practicality and art. This dynamic — that of practicality versus art; not of men being rude to women — is, as far as I am concerned, the beating heart of luxury. I know that, to some, luxury can be the pleasure of peace and quiet amid a household of hormonal children. It can be the privilege of a flat bed on an airplane, replete with a shower that won’t admit ‘more than two people at a time’, ahem.

While there is a subjective argument that luxury can be any one thing to any person, I stand by the theory that, in it’s truest form, luxury — through craftsmanship — bridges the gap between our everyday needs and art that reaches the same monumental heights of Bacon or Bach. This can be expressed in furniture, in tailoring, in watches and other accessories, in cigars and in various intoxicating beverages. Others have their own opinions on the matter, but if pressed lightly to make a choice, I’d say that the most profound expression of luxury in this sense is bespoke shoemaking.

In a previous Editor’s letter (Issue 60), I wrote of how my father’s collection of bespoke shoes is what effectively lies behind my path to The Rake. Wearing beautiful shoes wasn’t exactly supercharged with any social currency for me when I was young — indeed, highly polished full brogues or tassel loafers with jeans and a T-shirt didn’t bring the ladies a-flocking — but they did make me feel like the smartest person in the room, which henceforth became an objective wherever I went. I loved the idea that something so universal could be elevated to an upper echelon, a higher plain that stood out. Bear in mind that the environment I hung around in (namely Finch’s pub on the Fulham Road in south-west London) had a bus that went past the window that was dubbed the ‘Loafer Express’, so I was in good company, just a more fantastical version. The imposter syndrome did dwell on me, though: these were, after all, not my shoes, so in my mid-to-late teens I drifted into the muscularly aspirational demographic. And the desire was themed with a single name: Cleverley.

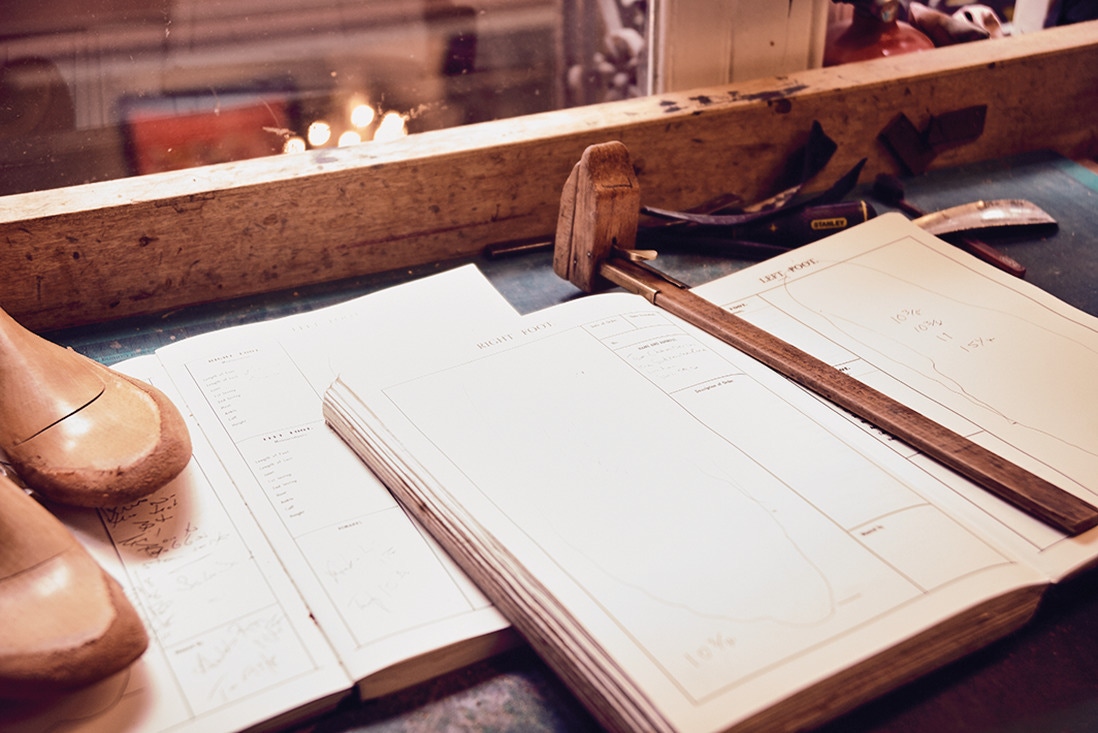

G.J. Cleverley, in the Royal Arcade, the tributary of shops between Bond Street and Albemarle Street in Mayfair, looks like it has been there for centuries. Like all the best British heritage shops, there is not much room but there is loads of character. There is a small showroom heavily laden with assorted styles of shoes, and a helical staircase in one corner that leads to the workshop, storage room and last room (depending on whether you go up or down).

The discretion is part of the appeal. A cursory look at the last room will demonstrate how Cleverley has attended to the feet of colossal cultural icons such as Ralph Lauren, Tom Hanks, Graydon Carter and Noël Coward. This is not meant to be a ‘scene’, though the popularity of the shoes around the world has made it something of a pilgrimage. And I was next.

The process of having a pair of bespoke shoes made is complex, exacting and, frankly, long. Whereas a suit will take approximately three months to make, a bespoke shoe might take a year the first time round (some brands are reported to take 18 months to two years). Now, credit to Cleverley, much of this is to do with the high volume of shoes they make bespoke, but nevertheless, there is a long wait, especially for someone with my levels of impatience and excitement.

The full version of this article appears in Issue 67 of The Rake. Click here to subscribe.