Life Through A Lens

Inventors of the point-and-shoot camera, and tireless in their quest to improve them, Leica are the custodians of photo-reportage: a responsibility they take very seriously indeed.

“Shooting with a Leica,” as the late master of humanist photography Henri Cartier-Bresson put it, “is like a long tender kiss, like firing an automatic pistol, like an hour on the analyst’s couch.”

Indeed, Leica doesn’t simply make cameras: their wares are the conduit via which the souls of the world’s most gifted photographers, and their human subjects, connect.

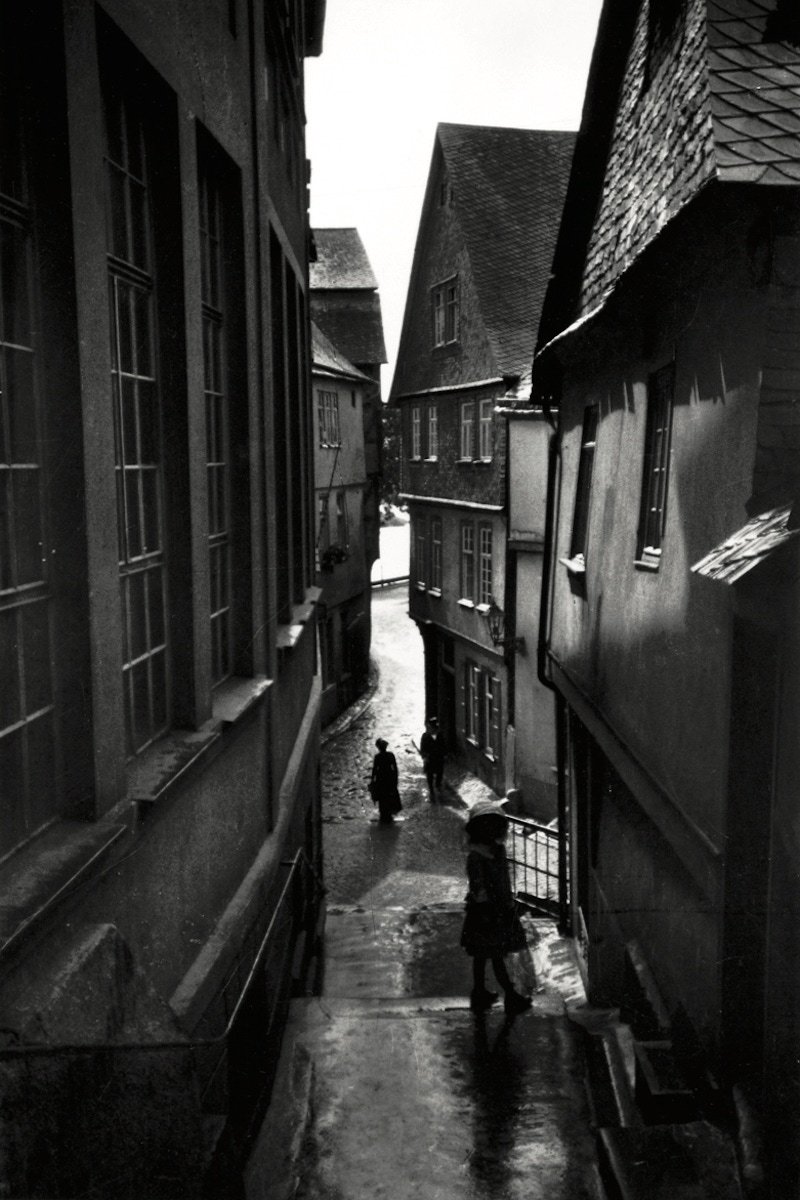

Their story begins in 1914 when Oskar Barnack, an optical engineer at a local microscope maker, came to a halt on the cobbled streets of Wetzlar, a small metropolis in the German state of Hesse. Having briefly surveyed the building in front of him - one of the thoroughfare’s many half-timbered structures from the Middle Ages - he took a small device from his pocket, held it aloft and, in an instant, made photographic history. Photojournalism was born.

It had taken just shy of a century to pass, since the moment Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the first ever photograph - a view from a window of his house in Chalons-sur-Saône - for this seminal moment in photography to occur. By the early 20th Century, cameras were still almost invariably cumbersome, heavy and unwieldy, whilst Barnack - who suffered from asthma - wanted to take his camera with him everywhere he went and capture images spontaneously.

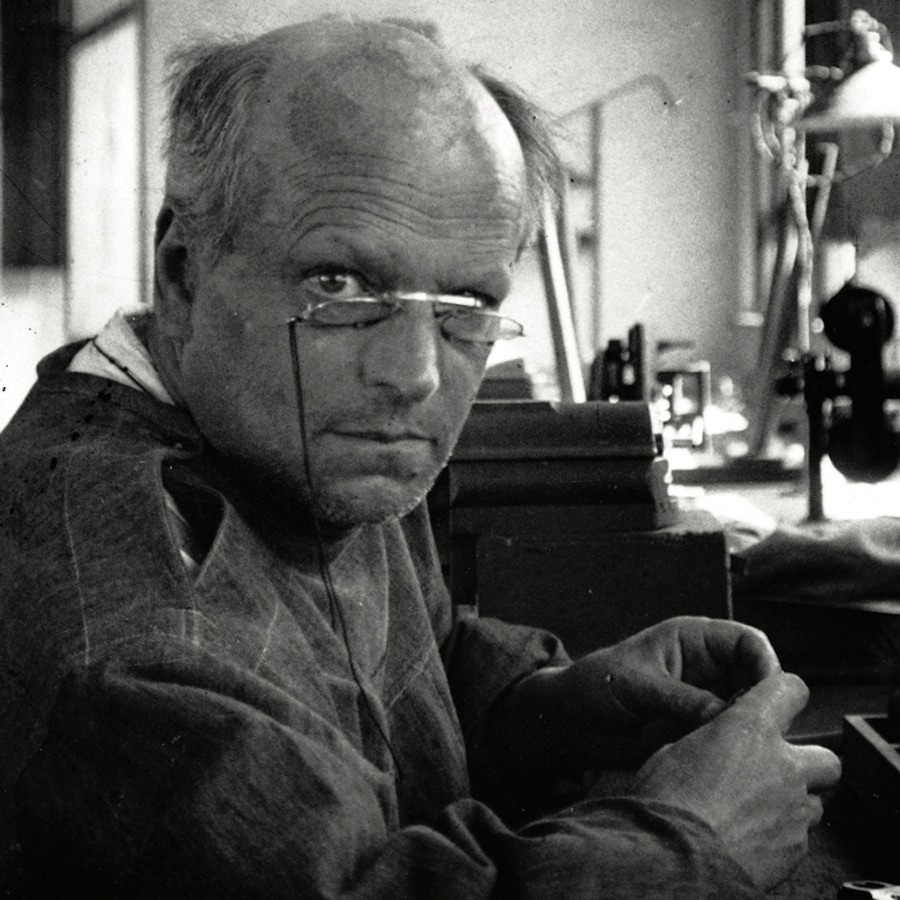

He achieved his goal by adapting 35mm cinematic film for still-camera use, a game-changing a masterstroke (the single line in his workshop journal alluding to his triumph - “Lilliput camera for cine-film completed” - seems almost comically modest). Barnack’s prototype, the Ur-Leica, was introduced to the market as Leica I at the 1925 spring fair in Leipzig - but he wasn’t done yet.

Having bestowed upon budding photographers freedom to capture moments spontaneously, dynamically, and in extremely high quality, he then developed a coupled rangefinder with interchangeable lenses, vastly increasing what photographers could capture, with clarity, within their surrounds. The third iteration of his invention introduced a separate slow speed dial, taking shutter speeds down to one second.

The German brand’s story since then is one of linear improvement, with nary a blip or a wasted second from Leica’s tireless R&D department. Breakthrough after breakthrough has come, milestone after milestone been laid: from Visoflex technology (which brought out all new opportunities for macro-photography) to the bayonet mount (enabling faster changing of lenses) to, more recently, mind-boggling innovations such as the ContentMapper, an airborne imaging sensor for large-scale geospatial mapping projects.

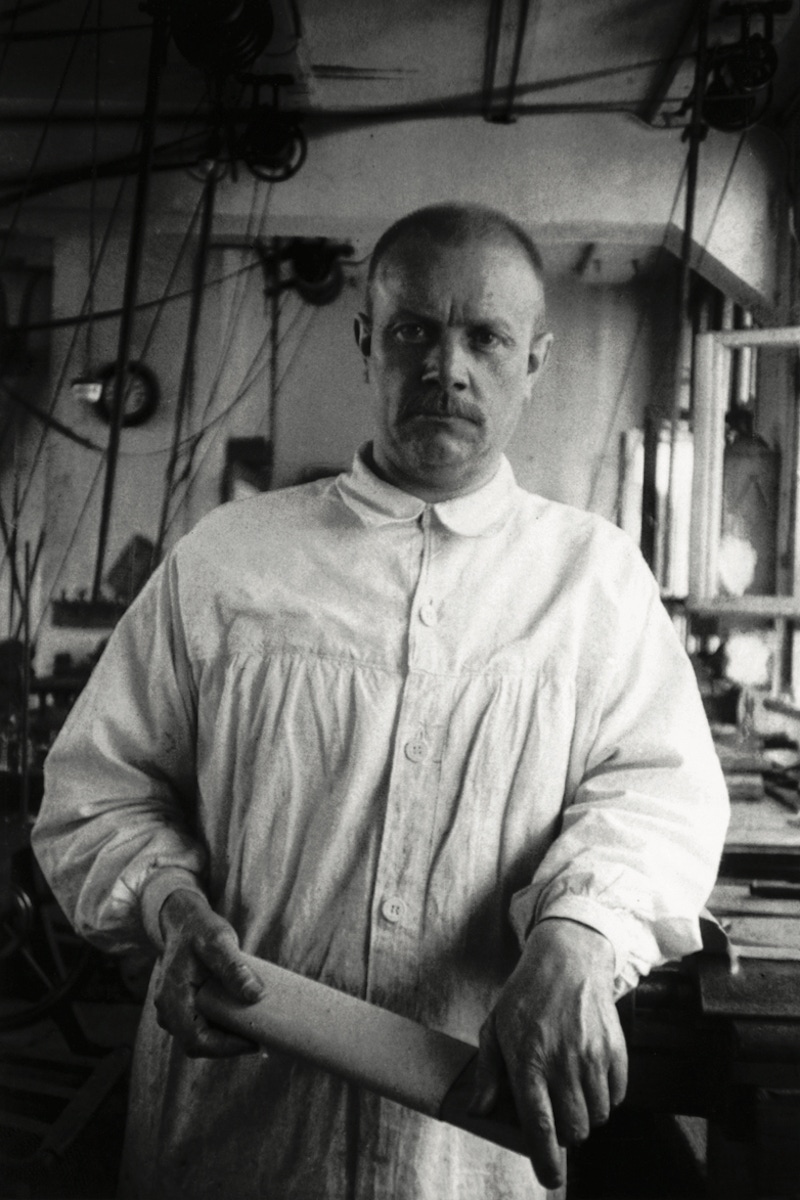

Today Leica is celebrated for, amongst other facets of its engineering prowess, the quality of its lenses. “Optics,” Dr Andreas Kaufmann, chairman of the supervisory board of Leica Camera AG, tells The Rake, “is all about how to capture light and how to paint with light”, and the passion, precision, innovation and expertise - built up over a century and a half - that goes into the hand-making of Leica lenses today is unsurpassed.

The obsessive attention to mathematically underpinned detail here speaks for itself: around 100 different types of glass are selected for the production of around 360 different lens elements; stray light around the lens is eliminated by precision coating and meticulous barrel construction; glass surfaces are treated with high-performance anti-reflex coatings, formulated especially for each glass type using geometrical calculations; aspherical surfaces minimise aberrations; even the water used in the jet-cutting of the glass is PH tested to ensure micro-perfection in the results. “Our R&D department of 180 people - software guys, artificial intelligence guys, censor guys, processor guys, and so on - is like witnessing witchcraft,” laughs Kaufmann.

There’s more than just the hardware, though, to a brand whose cameras have captured iconic images including Robert Capa’s The Falling Soldier, Cartier-Bresson’s Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare and V-J Day in Times Square by Alfred Eisenstaedt. “What’s a camera without the person behind it?” asks Karin Rehn-Kaufmann who, as Art Director & Chief Representative of Leica Galleries International, is custodian of the vast repository of creative endevour carried out using Leica cameras and presides over initiatives such as the annual Leica Oskar Barnack Awards. “Part of our mission is to take so much care of anyone who has a love for photography,” she says. “A camera is not just for taking pictures - it’s an instrument that should help people learn how to look at life.”

It is also an instrument which should, in stark contrast to the smartphones stuffed into our pockets, offer maximum creative autonomy to the user. Over, again, to Dr Andreas Kaufmann: “If you want life’s moments to become a little bit longer lasting, then you should want to do this with a camera with which you can collaborate with the laws of physics.”

No wonder the commemorative plaque which sits on that cobbled street in Central Wetzlar, where Oskar Barnack first held aloft his prototype hand-held camera, is a place of pilgrimage for those who truly understand the scientific, as well as the emotional, dynamics of photo-reportage.