Live Like a King: Clark Gable

Originally featured in issue 2 of The Rake, Christian Barker expertly delves into the golden era's ‘King of Hollywood’, ever-rakish actor Clark Gable whose effortlessly balanced elegance and machismo got him far.

Few stars of the silver screen provide as ample a testament to the transformative powers of the suit as Clark Gable. Described in an early review as being “young, vigorous and brutally masculine,” Warner Brothers boss Darryl F. Zanuck put it another way, succinctly stating of Gable: “He looks like an ape.”

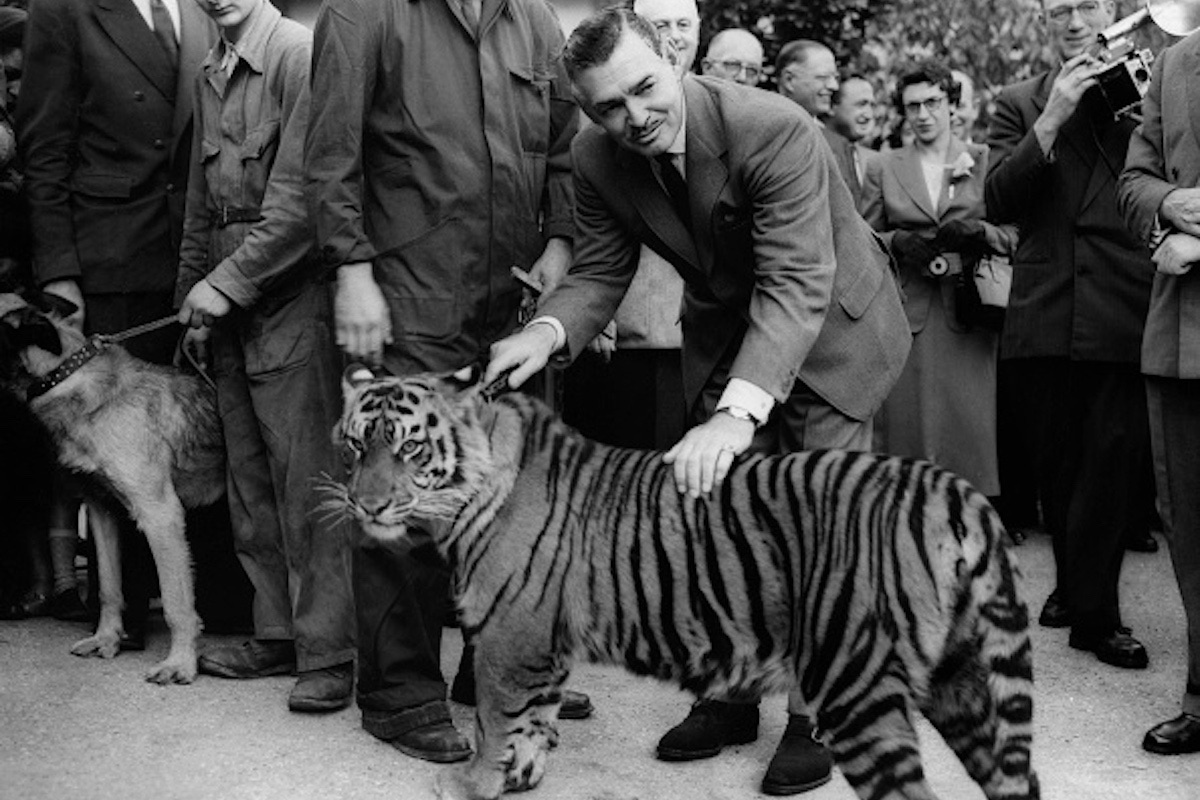

Yet it was precisely this rugged quality, offset by elegant attire and bearing, that formed the core of the actor’s appeal to the general public — in spite of his polished appearance, one could tell that beneath it all, Gable was no mincing thespian. Here was a real man — a “lumberjack in evening clothes,” as the studios’ marketing departments put it.

This dichotomy — a mix of red-blooded, outdoorsy manliness and refined sophistication — characterised Gable from his earliest years. Though, as a boy, he was encouraged by his father — an Ohio oil well driller and farmer — to engage in virile pursuits such as hunting, motor mechanics and tough manual labour, in private, Gable delighted in reciting Shakespeare’s sonnets, playing the piano and brass instruments.

Embarking on his theatrical career in his early 20s, Gable augmented sporadic income from infrequent appearances on stage not by waiting tables (as is so often the case with struggling actors), but via altogether more masculine means: working as a horse manager and labouring in the oil fields.

Women were always drawn to the rugged yet unfailingly immaculately turned-out actor, and it was thanks to financial assistance from his first wife — a Portland, Oregon, theatre manager named Josephine Dillon, who was a cougarish 17 years his senior — that Gable was able to polish his skills and physical appearance (having his teeth fixed and undergoing acting and voice training on Josephine’s tab), before eventually moving to Hollywood.

Here, after a number of inconsequential bit parts, a 1931 appearance as a villain in a B-grade western called The Painted Desert piqued moviegoers’ attention, and a flood of fan mail prompted Gable’s signing as a contract player with MGM.

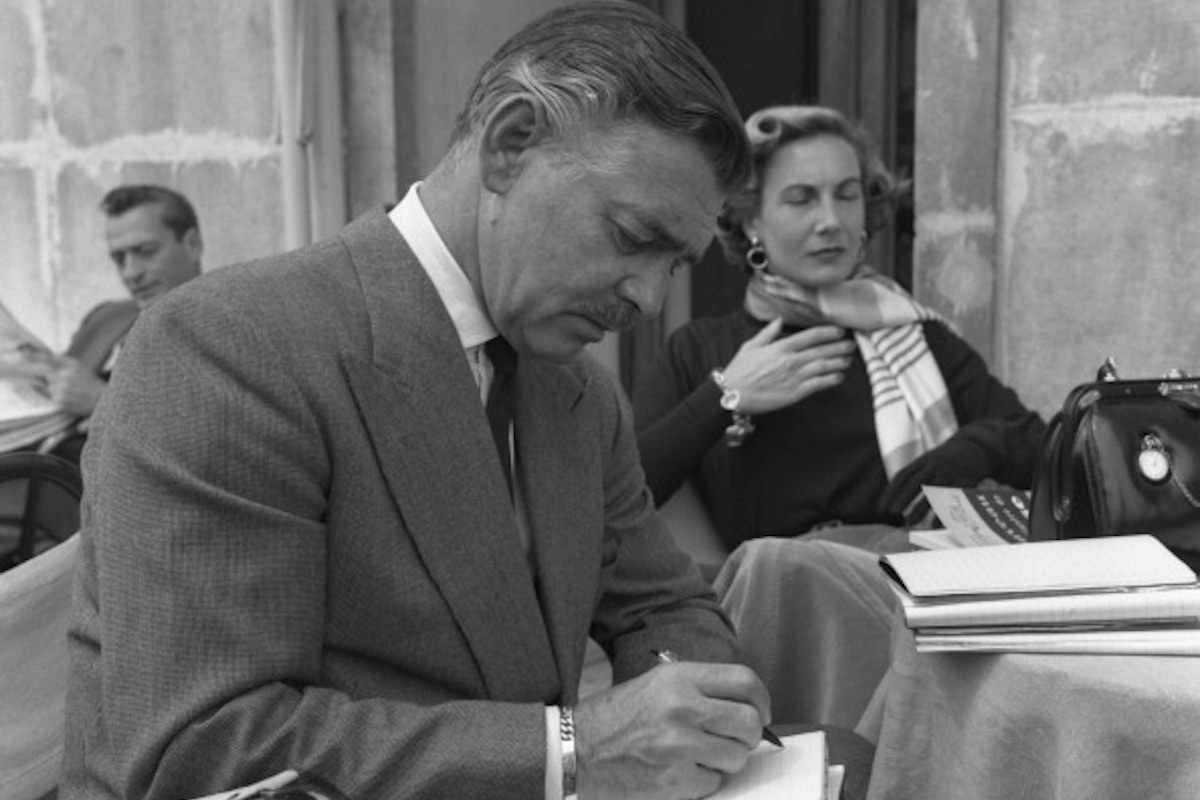

With his star in the ascendant, Gable found himself cast alongside the biggest actresses of the day, including Jean Harlow, Lana Turner, Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford — the last of whom he’d steal away from her husband, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. (no mean feat, considering Fairbanks’ status as one of the era’s leading matinee idols), and enjoy an on/off relationship with for many years to come.

A Best Actor Oscar for his performance in 1934’s It Happened One Night and a stellar turn as Lt. Fletcher Christian in 1935’s Mutiny on the Bounty cemented Gable’s status, and in 1938, he was labelled “King of Hollywood” in a newspaper poll voted on by some 20 million fans.

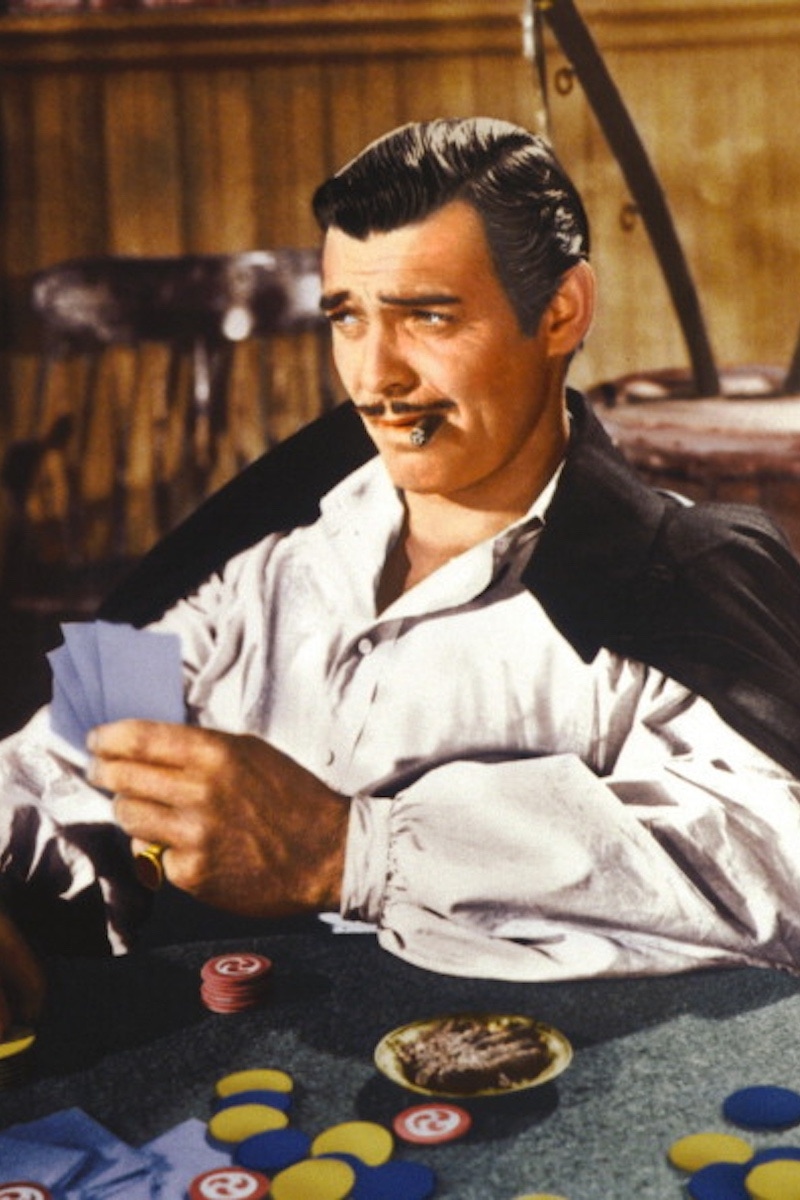

The following year’s civil war epic, Gone With The Wind, in which Gable played his most memorable role, that of roguishly irreverent, outspoken southern gent Rhett Butler, thoroughly confirmed Gable’s eminence as Hollywood’s reigning male star — and one of its greatest talents.

Regularly featuring in the top five on lists of ‘The Greatest Films of All Time’, when receipts are adjusted for inflation, Gone With The Wind remains the highest-grossing film ever. This success, we’d posit, was in no small part due to Gable’s nuanced performance, which again evidenced his ability to balance go-getting virility with a suave, cultured charm and — at times — vulnerable sensitivity.

Like the character of Rhett Butler, Gable was no stranger to tragedy, his third wife Carole Lombard perishing in a 1942 plane crash while on tour promoting war bonds. (Lombard was declared the United States’ first female casualty of World War II.) This prompted the actor to enlist — against studio wishes — for active service in the US Army Air Forces, where he served as an observer-gunner on B-17 bombers, flying several combat missions in the European theatre, winning the Air Medal and Distinguished Flying Cross in the process.

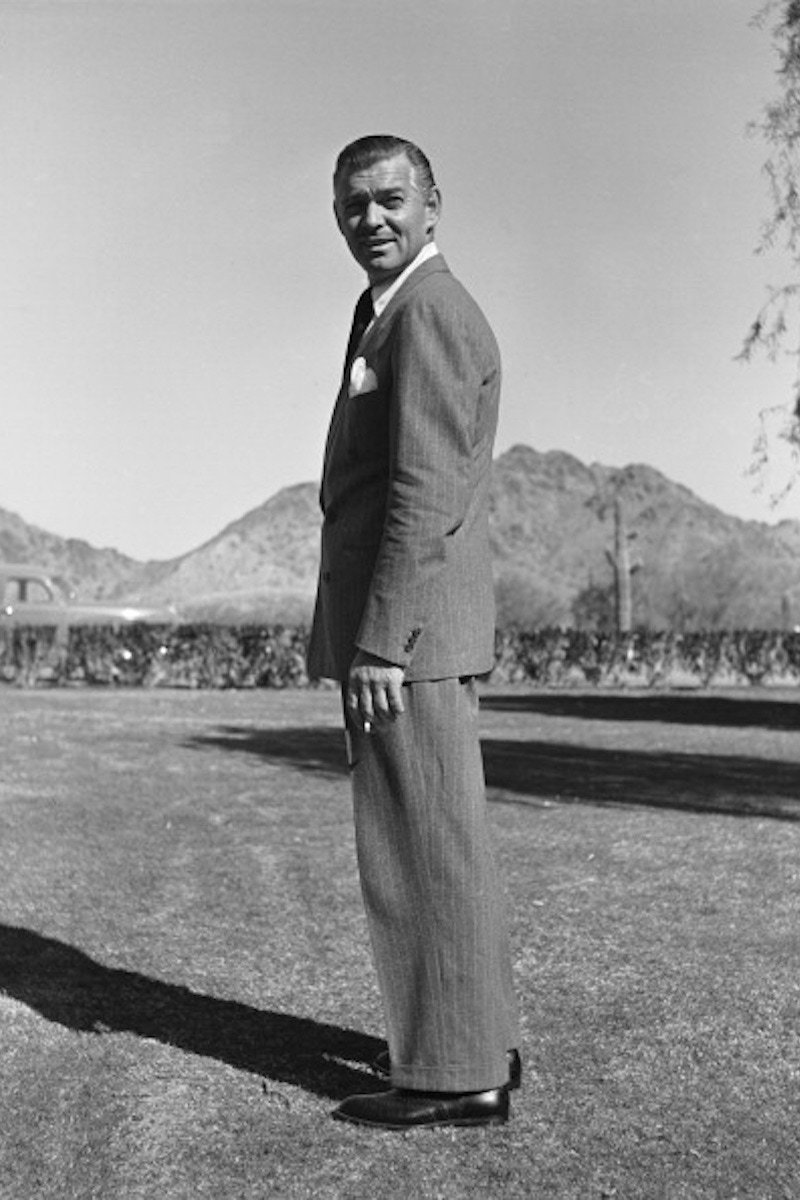

Though he continued to be a hit with the ladies (seducing a series of Tinseltown tasties including Mogambo co-star, Grace Kelly), Gable’s post-war movie career is considered fairly unremarkable, bar his final film, 1961’s The Misfits. The John Huston-directed, Arthur Miller-scripted drama (which would also be Marilyn Monroe’s final celluloid outing) produced what Gable believed to be his finest performance. However, the shoot was a taxing one — the 59-year-old actor had gone on a crash diet to get in shape for his role as an ageing cattle rustler, and with typical machismo, insisted upon performing his own stunts.

This man’s man, this “lumberjack in evening clothes” who’d smoked three packs a day, plus a couple of cigars and pipes, gasped his last just two weeks after shooting on The Misfits finished, having succumbed to a heart attack (his third) a few days after the cessation of filming.

To the end, however, he evinced a manner of graceful masculinity that any man might do well to emulate. Summing up his vision of manhood, Gable said: “The things a man has to have are hope and confidence in himself against odds... He’s got to have some inner standards worth fighting for… And he must be ready to choose death before dishonour without making too much song and dance about it. That’s all there is to it.”

Though his most famous line would have it otherwise, Gable clearly gave a damn. The man had a sterling sense of style, embodied an enviably urbane masculinity — and with parts well played and ladies well loved, his was truly a life well lived. Cowboy, playboy, soldier, star... We salute this self-described “lucky slob” — the King of Hollywood, and an archetypal Rake.