Lure of Duty: The Extraordinary Life of an Immortal Soldier

In the early stages of his military career, Adrian Carton de Wiart took hits in the ankle, hip, skull and ear, and he tore off his own fingers when a doctor refused to amputate them. We revisit Issue 40 of The Rake to discover it’s a good thing bodily trauma was so much to de Wiart’s taste, for his adventures had barely begun...

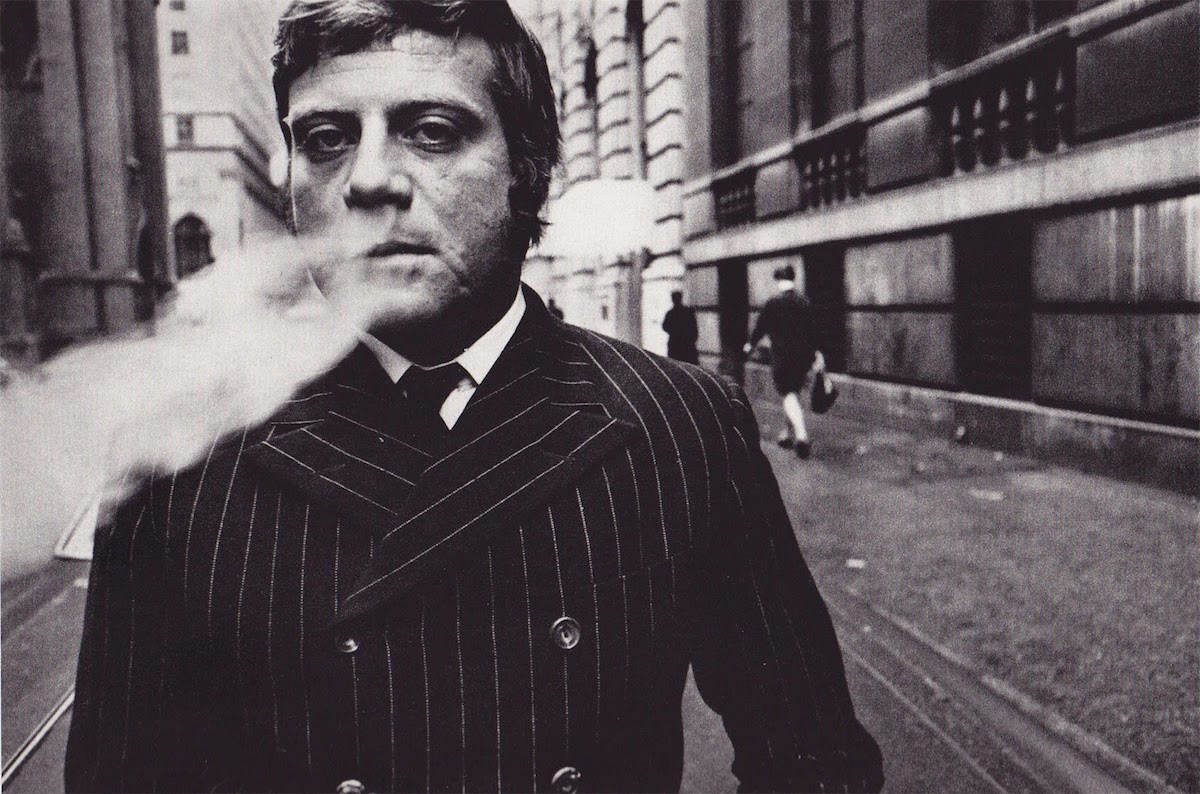

If there is one soldier in the history of military endeavour likely to make men of my ilk feel like pampered desk-jockeys, it’s Adrian Carton de Wiart: a Belgian-born British Army officer whose extraordinary life — and serial escapes from the jaws of death — prompt most who encounter his Wikipedia page to assume it’s some kind of Pythonesque satire.

Unencumbered by any ideological inclination, and narcotised by the smell of blood, de Wiart was doggedly loyal to any arbitrary cause that would pitch him against armed adversaries. In other words, he was the field-marshal’s dream and the pacifist’s nightmare. He was also utterly, resolutely unkillable: as prolific a casualty as any theatre of war has ever seen take centre stage, but never, ever to be commemorated by the blood-red flora of Flanders despite heavy involvement in three wars over four decades of military service.

De Wiart was born in 1880 in Brussels, but his family moved to Surrey, England, and then Cairo when he was a child. Like many children of well-to-do expats at the time, he was sent back to England for secondary education. He progressed to Oxford, where wine and cricket overshadowed any inclination towards academic endeavours. “I measured my contemporaries by their prowess at sport or taste in Burgundy and remained unimpressed by their mental gymnastics,” he later said of a period during which he ran up some hefty bills despite his father’s generous allowance.

Failing his law preliminary, de Wiart was drawn to the Foreign Legion — “that romantic refuge of the misfits” — but the outbreak of the Boer War sparked an epiphany in him: “At that moment I knew, once and for all, that I was determined to fight, and I didn’t mind who or what. If the British didn’t fancy me I would offer myself to the Boers.”

Having enlisted as a British subject under a false name and age, De Wiart found himself a member of a yeomanry regiment and aboard a troopship on a terrifyingly stormy voyage to Cape Town, much of which he spent cheerfully mopping up the sick of his landlubber comrades, not only impervious to the hazardous nature of his predicament but generally chuffed to be experiencing his first brush with mortal danger. On arrival in South Africa he was swiftly hospitalised with a bout of fever, but was released prematurely and randomly joined up with a bunch of local corps. Fighting with them, he copped the first of several bullets that would, over the course of his life, embed themselves in de Wiart’s corporeal form — this one in the groin.

“I do not think it possible for anyone to have had a duller dose of war,” he later wrote, having been invalided back to the nursing home on Park Lane, London, that would become his second home over the course of the next few years. “I returned [to England] bereft of glory, my spirits deflating with every mile.” Once recuperated, he journeyed to Egypt to ask his father’s permission to commit his life to martial endeavour. After some persuasion, de Wiart senior gave his blessing, and shortly afterwards the young, thrill-seeking militiaman arrived back in Cape Town to joined the Imperial Light Horse Colonial Corps, who promoted him to corporal within days, then demoted him within 24 hours for threatening to deck his sergeant.

His potential was manifest to those in senior ranks, though, and it wasn’t long before de Wiart progressed to officer. Yet this was little consolation for a life so woefully lacking in action: “My vivid imaginings of charging Boers single-handed and dying gloriously with a couple of V.C.s were becoming a little hazy.” Before long, he was gazetted to the 4th Dragoon Guards and stationed in India, where he took up horse-mounted pig sticking — a highly boisterous hobby that involved numerous high-speed falls, one of which saw his rib cage and ankle partially crushed when a horse rolled over him.

De Wiart’s time in India generated some happy memories, but not for the first time in his life, the lack of life-threatening combat left him knee-deep in nihilism. “India for me was a glittering sham coated with dust, and I hoped I should never see her again,” he wrote.

Eventually returning to what had become his motherland and joining his regiment in Brighton, de Wiart distracted himself from the vacuous banality of peacetime by taking part in polo matches (in one match he ‘bumped’ his leg, carried on playing, then realised after the game he’d broken it) and making occasional jaunts to Austria, Hungary, and what was then Bavaria to spend the interwar years shooting deer, chamois and pheasants.

Accepting an adjutancy with the Royal Gloucestershire Hussars, his plans changed in 1914 when his father broke the news that he had been ruined financially due to the crash in Egypt, and an allowance would no longer be forthcoming. Soldiering in England not being sufficiently well paid to sustain him, de Wiart again sought active service abroad. His intended destination — Somaliland, where a low-key war effort was being waged against Mohammad ‘Mad Mullah’ bin Abdullah — required a promotion to major, and despite scoring just eight out of 200 for Military Law, he set sail for the north-east African coast in July 1914.

By his own admission, de Wiart’s “cup of misery overflowed” when he discovered, during a stop-off in Malta, that England had declared war on Germany. In light of this development, his forthcoming station of duty “felt like playing in a village cricket match instead of a Test”. De Wiart’s hunger to have his mortality tested in new and interesting ways was soon sated, though, during a testy battle with bin Abdullah’s Dervish forces: one bullet whistled through his rolled-up uniform sleeve; the next went through his eye, but still he barely broke his stride; the next hit required the plucking of a bullet splinter from his elbow; the one after that required the services of a nearby surgeon to stitch up his ear.

Makeshift repairs to de Wiart’s physique done, he soldiered on and attempted to storm a blockhouse, but another bullet ricocheted through his already damaged eye. Yet what was it that eventually persuaded de Wiart and his comrades to withdraw to camp and assess their situation? Bad light. “Rather magnanimously, we offered the Dervishes their lives if they would surrender, but our generous gesture brought forth a still brighter volley of rudery as to our parentage,” he later wrote. “It had all been most exhilarating fun, and the pace too hot for anyone to have had any sensation but thrill, primitive and devouring.”

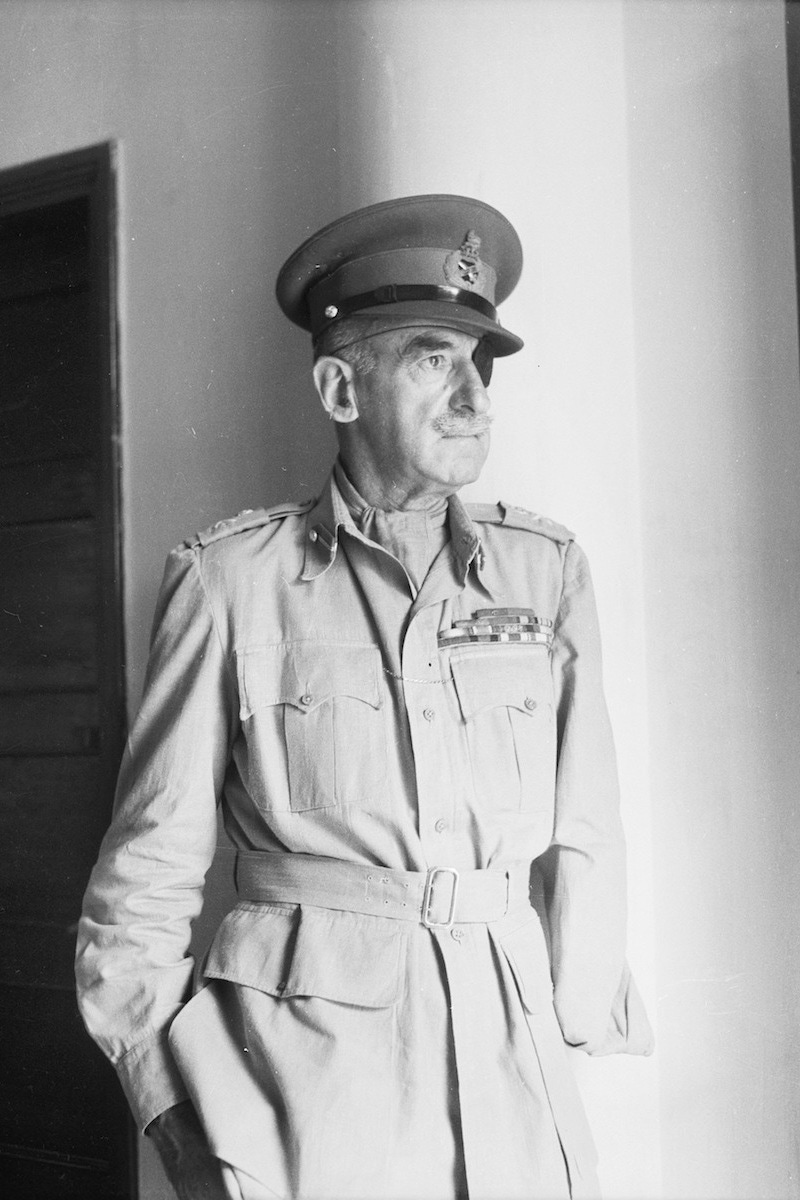

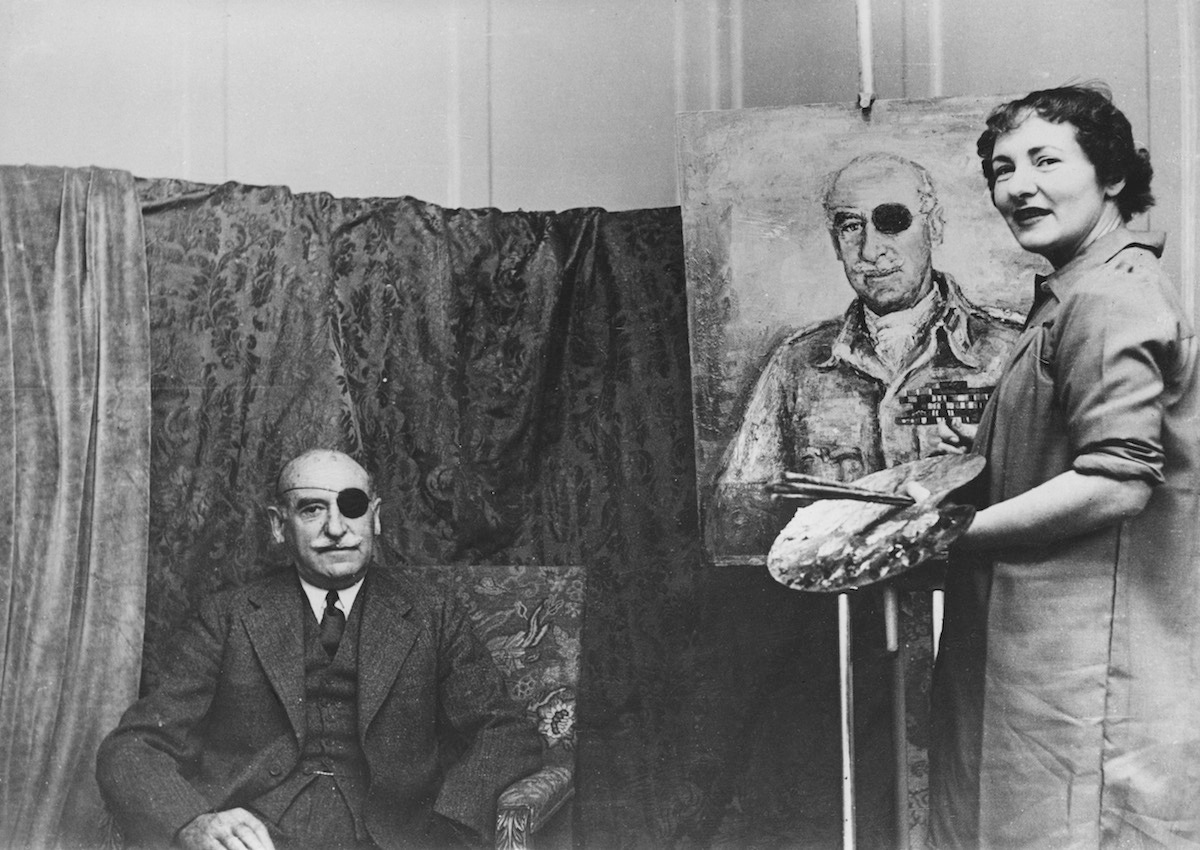

Sent to Egypt on a steamer for treatment, he refused to allow an eye specialist there to remove his mangled optic, as the injury afforded him a chance to be sent back to Blighty, where he might become a protagonist in the theatre of what he considered to be a real war. It was a wish that, once his eye had been removed and replaced with a glass one, the British military granted. Having been passed fit for service, de Wiart hurled the glass eye out of the window of his taxi home, and from then on sported the black eye-patch that, along with his empty sleeve, made up the trademark uniformed pirate look with which he is still associated today.

It was on the Western Front, in Ypres, in the summer of 1915 that de Wiart’s hand succumbed to German fire, leaving two of his fingers hanging by some skin and his palm and wrist annihilated. When the doctor refused to amputate the fingers, de Wiart tore them off himself. Invalided back to London again, he underwent numerous operations whereby more and more of his hand was chopped off. Eventually, with only a spot of laughing gas to numb the pain, they amputated his hand (“the whole entertainment was no worse than having a tooth out”, was his assessment of the ordeal).

Miraculously passed fit again for general service, de Wiart was engaged in a night raid on High Wood in the Somme when he felt a sensation like the entire back of his head being violently removed. Again he was sent back to Park Lane. “After an examination the surgeon pronounced my skull intact, ordered me a bottle of Champagne, and told me that by a miracle a machine gun bullet had gone straight through the back of my head without touching a vital part. The only after-effect of this wound was that whenever I had a haircut the back of my head tickled.” As soon as he had recuperated, de Wiart returned to the scene of the incident and promptly took a fragment of shell in the ankle and, shortly afterwards, the ear.

As well as being tenacious, it must be said that de Wiart was also fortuitous: having been shot in the hip in Cambrai, northern France, with the uniform fabric blasted into his flesh turning the wound septic, he was safely ensconced in the dressing station when his headquarters got bombed, an attack that caused several fatalities. After the first world war, stationed in Poland to help fend off attacks by Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Russians and Czechs, he survived a machine-gun attack on a train.

Around the same period, travelling up to Riga in Latvia to take on the Bolshevik machine — flying at low altitude due to bad weather — he spotted a German soldier on the ground taking a rifle shot at the plane. On disembarking, he noticed a bullet hole six inches from his seat. On another occasion he crawled unharmed out of a crash-landed aircraft only because it had run out of fuel and therefore didn’t explode. He probably offered the matter only a single raised eyebrow when, following a period in Lithuanian custody during the Vilna Offensive, de Wiart found himself reading his own obituary in a Berlin periodical.

He enjoyed a lengthy, peaceful and relatively uneventful hiatus between the wars, but de Wiart no doubt felt a frisson of excitement when Neville Chamberlain announced that the British deadline for the withdrawal of German troops from Poland had expired, and he joined the second world war effort with zeal.

It wasn’t long before he experienced his third airborne lucky escape. He was flying in a Wellington Bomber on one leg of a convoluted trip to Belgrade in order to negotiate Britain’s involvement with Hitler’s imminent invasion of Yugoslavia — by now, of course, de Wiart was a senior figure in the British military — when the pilot made an S.O.S. call and crash-landed a mile-and-a-half from the Italian coast. Awoken from unconsciousness by the body-convulsing temperature of the water, he managed to help various shattered-limbed comrades to shore only to be captured by Italian troops on arrival. Becoming one of the highest-ranking prisoners of war in the entire conflict, he orchestrated five escape attempts, the most audacious of which involved a seven-month tunnel-digging project that gave him his liberty for an entire week.

It’s easy to forget, amid the harrowing tales of a soldier who sacrificed so much of his body, that Adrian Carton de Wiart was a man of extraordinary influence. By birth he was a cousin to former Belgian prime minster Count Henri Carton De Wiart. Rumours abounded among his contemporaries that he was an illegitimate son of Belgian king Leopold II. While fighting as a brigadier general at the Battle of Arras, de Wiart met King George V, who expressed extreme displeasure that de Wiart was still not a British subject, having served in the army and risked life and limb for more than 10 years.

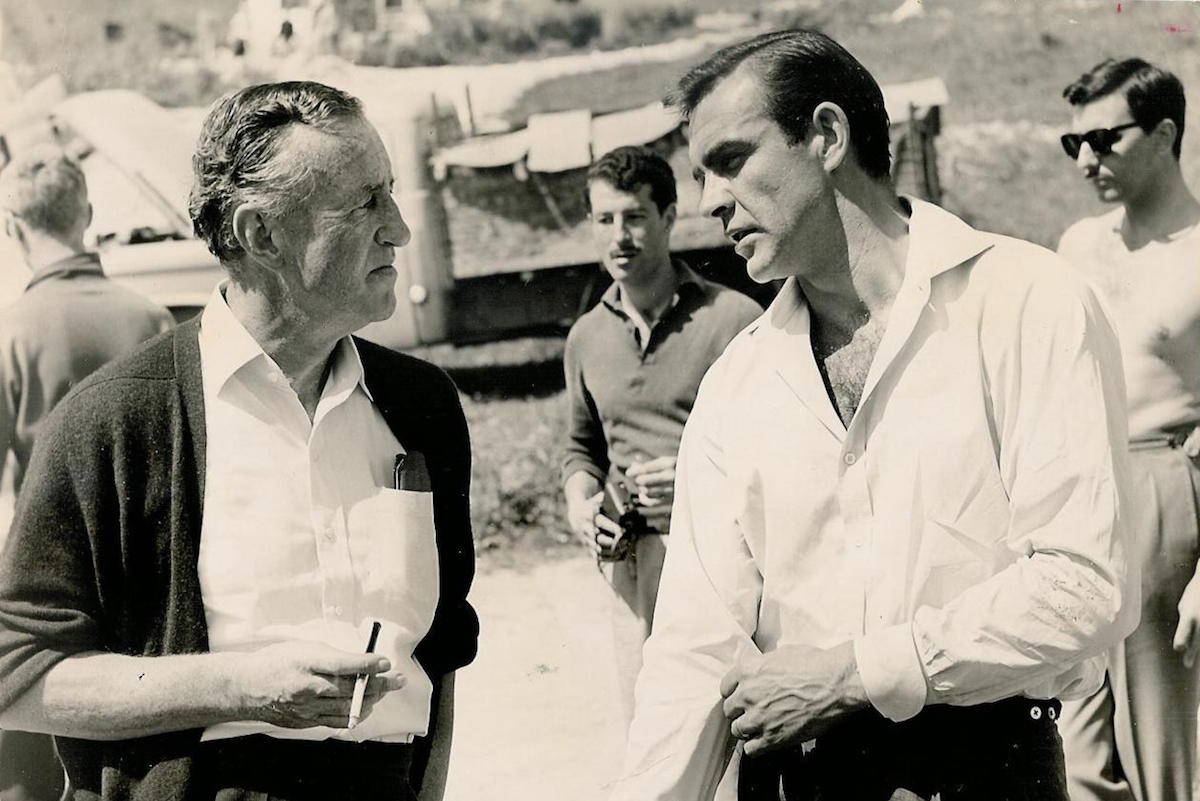

He once gained an audience with Lloyd George to try to persuade him to give Eastern Galicia to the Poles, and Winston Churchill, towards the end of the second world war, sent de Wiart to China to be his personal representative — the high point of his mission was ticking off Mao Zedong at a dinner party for China’s soft stance on Japan in the war.

Even on his retirement, de Wiart showed an insatiable appetite for injury. Having hung up his army fatigues for good, and returning home from his duties in the east via French Indochina, he stopped in Rangoon as a guest of an army commander. Coming down some stairs, he slipped on coconut matting, fell down, broke his back and several vertebrae, and knocked himself unconscious. There could not have been a more fitting conclusion to his career.

Not a great deal is known about de Wiart’s dalliances with the fairer sex. The man was a gentleman in every sense of the word in interwar Britain, and therefore discreet on such matters in his riveting autobiography, Happy Odyssey (which, incidentally, should be meted out as compulsory reading for any man who ever dares to bemoan having stubbed his toe). The same tome, though, does include a passage that offers some insight into de Wiart’s leanings when it came to gender dynamics and old-fashioned chivalry. Shortly after the first world war, a peer at his London member’s club asked him to fight a dual with a man who was giving unwanted attention to a woman of his acquaintance. De Wiart challenged the man, rebuffing his would-be opponent’s qualms about the law by pointing out that the loser could simply be taken to a secluded spot, doused with petrol and cremated. Understandably petrified, the man instantly wrote an affidavit agreeing not to trouble the lady in question again. “It was a tame end,” reflected a disappointed de Wiart. “It seemed to me that, as he did not like the lady enough to fight for her, he needed a thrashing.”

His two marriages are barely touched upon by any existing biographical material. What we do know is that his first wife died in 1949, and in 1951, at the age of 71, de Wiart married a divorcée 23 years his junior and settled in County Cork, Ireland, seeing out his days in hot pursuit of salmon and snipe. Some of his magic clearly rubbed off on his second spouse, as she lived until the age of 102.

Perhaps a fitting conclusion to any account of Adrian Carton de Wiart’s life, though, is a list of his official honours: the Victoria Cross, the Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Companion of the Order of the Bath, Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, the Distinguished Service Order, the Belgian Croix de Guerre, and Officer of the Order of the Crown of Belgium.

And not only all of that, but possibly the most eyebrow-hikingly fascinating old bruiser The Rake has had the pleasure of profiling.

This article was originally published in Issue 40 of The Rake. Click here to subscribe.