For A Muse of Fire

Previously in the shadows, the muse—she who inspires “the brightest heaven of invention”, as The Bard put it—has stepped out once more and blossomed into a style and pop-cultural icon.

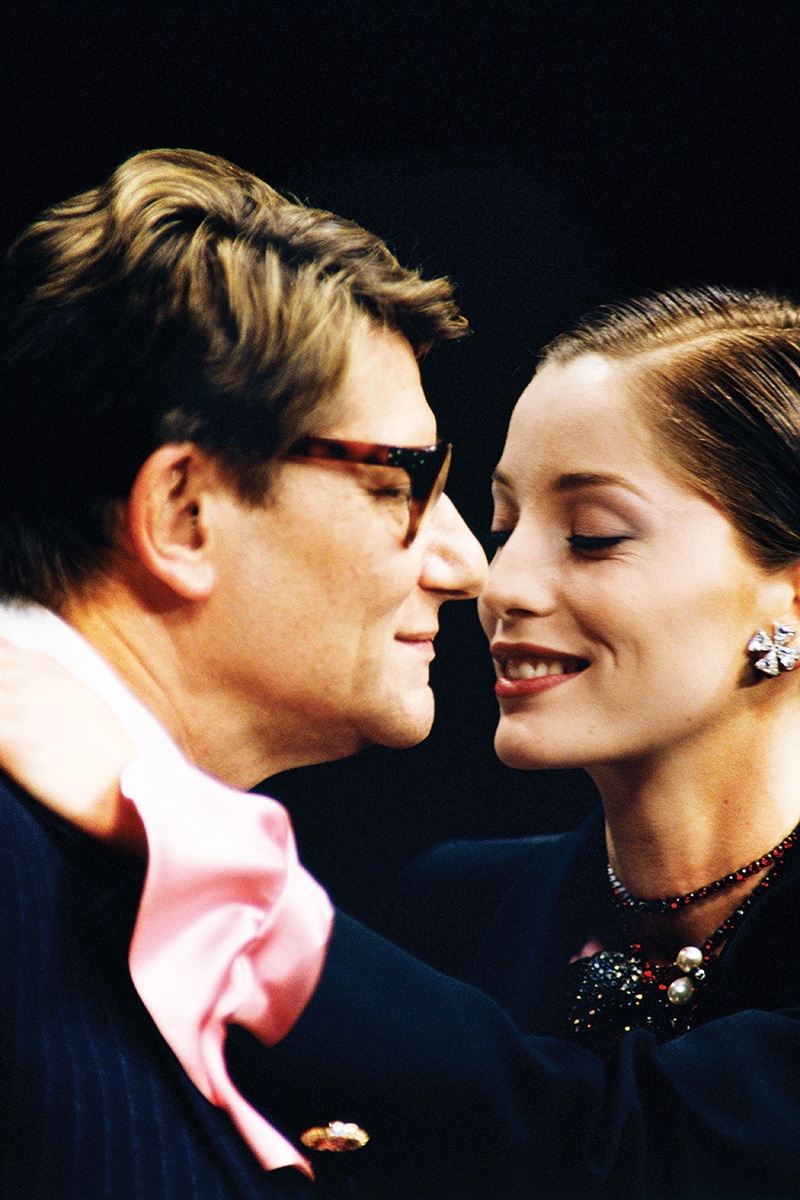

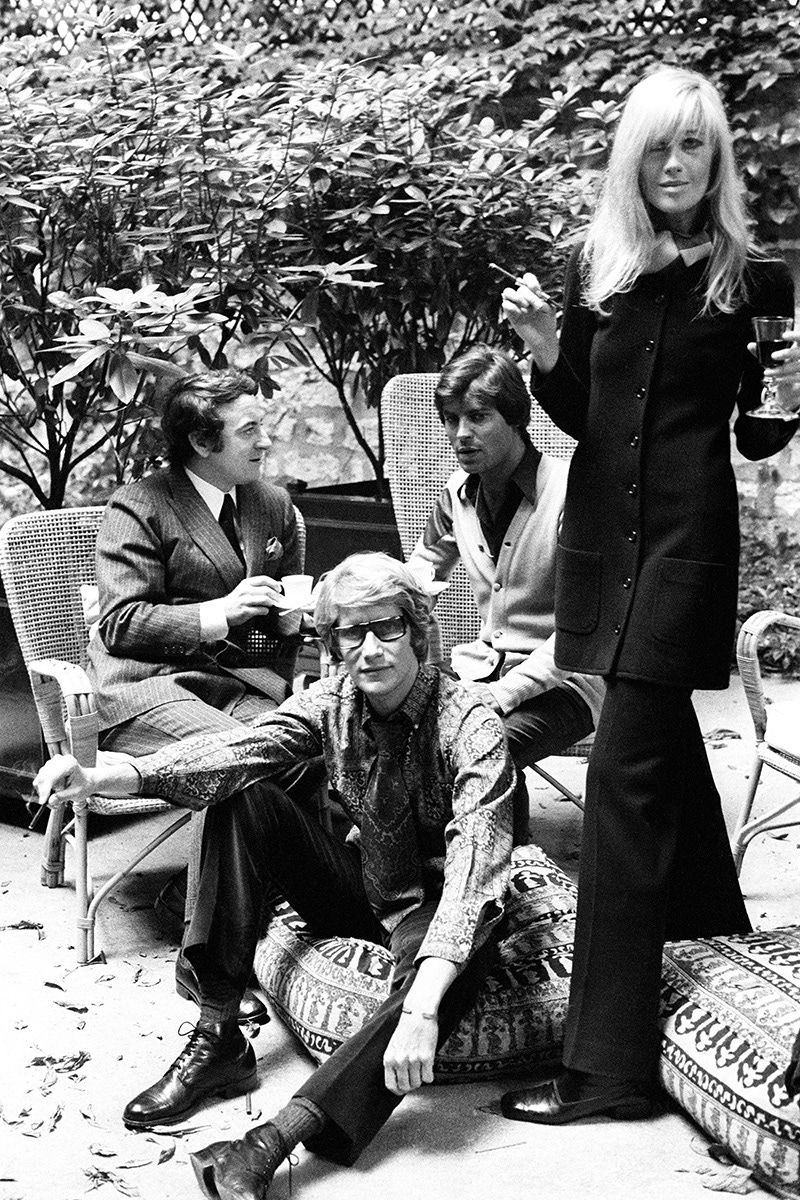

The night was young in Gay Paree, certainly for the nocturnal creatures of the demi monde who inhabited the infamous Régine, the gayest of the gay nightclubs. The year was 1967, and what happened that fateful evening across a crowded discotheque floor would mark the beginning of one of the most legendary kinships in fashion history. Through the louche haze of smoke and strobe lights, a leather-clad Yves Saint Laurent locked eyes with an impossibly languorous, leggy and platinum-tressed Betty Catroux and it was coup de foudre. Saint Laurent saw in Catroux a reflection of himself—here was his ‘twin’, his feminine alter ego.

As the feted interior decorator François Catroux (Betty Catroux’s husband) said inThe Beautiful Fall, Alicia Drake’s captivating chronicle of hedonistic 1970s fashion excess in Paris,“She was a pencil stroke that was his pencil stroke. She is what he would have dreamed of being himself, I guess.” And thus began a symbiotic relationship between fashion designer and muse which would come to span over three decades and produce tours de force such as LeSmoking, as immortalised by Helmut Newton. Woman kind has Catroux and her trademark tom boy style—sharply cut blazer plus skinny trousers, usually in black, have been her uniform of choice since the 1960s, when a woman in man’s clothing was deemed out réto say the least— to thank for inspiring Saint Laurent to use masculine tailoring tropes to revolutionise womenswear.

Geniuses of Yves Saint Laurent’s magnitude, of course, have a proclivity forgathering iconic women about them. The late Louise Vava Lucia Henriette le Bailly de la Falaise — better known as Loulou de la Falaise, daughter of the raving beauty Maxime de la Falaise, herself a muse to Elsa Schiaparelli—was Saint Laurent ’s other woman, the yin to Catroux ’s yang, and her flamboyant, accessorised-to-the-hilt, eccentrically exotic, bohemian-princess style would inspire the other strain in the manic-depressive designer’s body of work—the strain that captured the beat nikzeitgeist of the era, and which prolifically channelled Saint Laurent’s fascination with his beloved Marrakesh. Saint Laurent had first met de la Falaise in1968, and by1972, was so besotted with her, he invited her to come work alongside him designing jewellery and hats.

On her unique collaboration with Saint Laurent, she told Vogue: “We both believe fantasy is such a vital element of fashion.We tend to think of ourselves as gypsies who have just returned with a marvellous caravan of incredible finds from the exotic reaches of the earth. But we have to make the caravan ourselves. Our Orient is our imagination.” The luxe hippie- chic aesthetic came to be synonymous with beauties like Marisa Berenson, whom Saint Laurent hailed as “the girl of the ’70s”, and Talitha Getty, who is best remembered posing in a kaftan, harem pants and knee-high boots for a 1969 photograph taken by Patrick Lichfield on a Marrakesh rooftop. It’s an image so emblematic of the era that Saint Laurent has wistfully commented,“I knew the youthfulness of the ’60s: Talitha and Paul Getty lying on a starlit terrace in Marrakesh, beautiful and damned, and a whole generation assembled as if for eternity where the curtain of the past seemed to lift before an extraordinary future.” This was the late ’60s—the youth quake was rumbling underfoot, and Saint Laurent instinctively knew to dissociate himself from the stuffy ghosts of haute-couture past and embrace the future’s new generation.

The subject of the muse is an enigma that stirs in the human breast a similar dialectic of inquiry as questions such as what is art and what is beauty. Just as ordinary language is too poor to describe that which is art and that which is beauty, it often feels equally in adequate to the task of expressing the mystical cord that binds artist to muse. And in the not uncommon scenario where the brilliant artist in question is a homosexual fashion designer, where you can take away from the equation ties messily shaded by coital relations, there in lies the rub.If sex surely coloured the relationship between heterosexual painter and muse in the aforementioned art world cast of lovers and spouses,then the absence or ambiguity of sex must just as surely influence the bond between homosexualor bisexual fashion designer and muse.

The characterisation of the bond seemingly recedes from the lustily corporeal extreme of the scale and moves towards the deified, Platonically idealised,worshipped-on-a-pedestal scheme of things. Less promiscuous, more chaste — which is not to say more innocent — and apparently closer to the original invocation of the Muse. Although, if you pay any heed to psycho analytic theory, it would claim that this all still boils down to in flagrante delicto of the repressed variety that Freud with his Oedipus complex and Jung with his Electra complex had their knickers in such a twist about.

The bond may very simply be reflexive in nature. Like Narcissus gazing upon his reflection, the designer sees mirrored in his muse a kindred spirit, a woman born to look fabulous in his clothes and elucidate to the world-at-large his vision and design ethos. In which case, a designer as profligate in the anointment of muses as Karl Lagerfeld is making a statement that’s as much about his mouthy megalomania as his undeniably profuse creative output. Most memorable of them all is probably Inès de la Fressange, whose contretemps with Kaiser Karl in 1989 over her decision to lend her likeness to a bust of Marianne(a decision Lagerfeld condemned as being terribly“bourgeois”) is the stuff of fashionlore; they’ve since kissed and madeup, with de la Fressange walking the Chanel spring/summer 2011 show. She had, however, moved on quite some years ago, signing up as brand ambassador for Roger Vivier, where in an interesting twist on the designer-muse dynamic, she was the one who recommended Bruno Frisonito Diego Della Valle (Chairman of Tod’s Group, which owns Roger Vivier) as the ideal candidate for resuscitating the fabled label responsible for shodding exquisitely-YSL-clad Catherine Deneuve in signature buckled pilgrim pumps in Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel’s provocative 1967 film. These days, de la Fressange has also been roped in by Della Valle as consultant at born-again Schiaparelli alongside Farida Khelfa as spokesperson.

It is testament to Lagerfeld’s remarkable longevity in a notoriously fickle industry that his list of muses reads like an It girl directory through the ages. Lady Amanda Harlech is a long time collaborator at Chanel, so much so that her daughter Tallulah has now joined the ranks of front-row aristocracy. Actress/model muses abound, the most prominent being Vanessa Paradis, Keira Knightley, Anna Mouglalis, and Clémence Poésy. As do rock-chick/model hyphenates, like Lou Doillon, Caroline de Maigret and Alice Dellal (who fronts the Boy Chanel campaign).There’s no shortage of heiress/socialite muses; the Courtin-Clarins cousins alone already account for four. And of course, we have not even grazed the official roll call of hipster brand ambassadors, including style-mavens- about-town like stylists Vanessa Traina and Caroline Sieber, photo-agent-turned-creative-consultant Jennifer Brill, model/socialite Poppy Delevingne and DJ/model Leigh Lezark. If muse collecting were a bloodsport, Lagerfeld would be the undisputed UFC (bantam weight) champion of the universe.

Vibrant, dynamic muses like Loulou de la Falaise, Inès de la Fressange and Amanda Harlech show that the role of the muse in fashion can be far more than skin-deep, and certainly far more interesting than that of a beautiful but passive clothes horse perched atop a podium for all to admire. Her exact function, while destined to forever be nebulous in definition and varies from case to case, does not consist of being ornamental and wafting about ethereally through the atelier, as may be the popular conception. She is the hand that gently nudges in the right direction; her voice is heard, embodying as she does the woman whom the designer wants to dress in his mind’s eye. The designer defines the muse as much as the muse defines the designer. Think of Nicolas Ghesquière during his15-year tenure at Balenciaga, and you’ll think of Charlotte Gainsbourg, the unconventional yet mesmerising beauty who wears his avant-garde designs with insouciant panache. Or think of Marc Jacobs, and you’ll think of Sofia Coppola, who does ladylike-classic-with-a-twist with effortless chutzpah.

The empowered muse is not a recent development. From the outset, relationships such as that between Christian Dior and Mitzah Bricard, or Hubert de Givenchy and Audrey Hepburn (to whom lazy women the world over owe a debt of gratitude for the perennially appropriate garment also known as the ‘Little Black Dress’), were delineated by their working nature. The former is not unlike the relationship between Yves Saint Laurent and Loulou de la Falaise, a conspiratorial one between bosom friends and professional collaborators (the difference being that quite unlike de la Falaise, Bricard purportedly never ever donned any Dior).In the latter, it’s a mutually munificent relationship between designer and high-profile patroness-turned-muse.

It is this liaison between designer and patroness-turned- muse that has shaped a significant swathe of the 20th-century fashion landscape. There is no question as to who the queen bee of patroness muse-dom in the 20th century was. During its first three decades, one woman stood out as much for her generous patronage of the arts as for the scandal that trailed in her wake and her marvellously bizarre persona. In her quest for immortality, Marchesa Luisa Casati — who routinely wore live snakes as jewellery and thought no thing of walking her cheetahs on diamond-studded leashes whilst naked beneath her furs — had herself painted, sketched, sculpted and photographed by legions of artists. She patronised and inspired everyone from Giovanni Boldini to FT Marinetti to Man Ray. The original female dandy who hosted the most decadent of masquerade balls, she was dressed by Paul Poiret, Mariano Fortuny, Erté and Madeleine Vionnet.

This most original of muses may have passed away in 1957, but her artistic and cultural legacy continues to be a rich source of inspiration for fashion designers. John Galliano’s spring/summer 1998 and autumn/winter 2007 haute-couture collections for Dior were unabashed paeans to the Marchesa’s fearless style, with the 2007 Bal des Artistes collection including a gown based directly on Boldini’s 1908 portrait of his bewitching muse. Alexander McQueen’s spring/summer 2007 ready-to-wear collection and Kar lLagerfeld’s 2009 ready-to- wear cruise collection for Chanel are another two outstanding examples of the Marchesa’s ability to beguile and inspire beyond her grave — as she would surely have wished.

The Marchesa, it goes without saying, is a radical example of a patroness-turned-muse. A cursory glance through the client books of the mid-century’s most significant fashion designers will show that there was a very particular set—the so-called ‘jet set’ in the original sense of the term as coined by Igor ‘Cholly Knickerbocker’ Cassini—they clothed. Privileged beauties with purchasing power, these were women who populated a rarefied social milieu, many of them Truman Capote’s ‘swans’.These habitués of the International Best Dressed List were frequently photographed by the likes of Bert Morgan and Slim Aarons, and included among others Babe Paley, Slim Keith, Gloria Guinness, Marella Agnelli, CZ Guest, Lee Radziwill, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Pauline de Rothschild, Mona Bismarck, Millicent Rogers and Jacqueline de Ribes. Helen of Troy may have launched a thousand ships, but all it took was a photograph of someone like Babe Paley with a scarf tied to her pocket book to trigger a trend imitated by millions of women. It’s hard to imagine modern fashion muses like Lauren Santo Domingo, Alexa Chung or Daphne Guinness having the same effect, formidable as their style may be.

Somewhere in her evolution, the muse had stepped out from behind the designer and metamorphosed into a style and pop- cultural icon. So great was her charisma, she was inspiring not just the designer, but also the masses.That’s quite the change from the traditional conception of the muse, who was always in the shadows and whose function was not to inspire emulation but the creation of art.The definition of the muse became even more amorphous and all-encompassing with the opening of the 2009 exhibit‘The Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion’ at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Co-curator Harold Koda has clarified the exhibit’s definition of muse to say that the models featured did much more than inspire the designers and photographers they worked with. “There are certain women in certain periods with whom you identify with the fashion of the time...What we are saying is that she becomes the embodiment of fashion. So everybody absorbing her image uses her as a muse.”

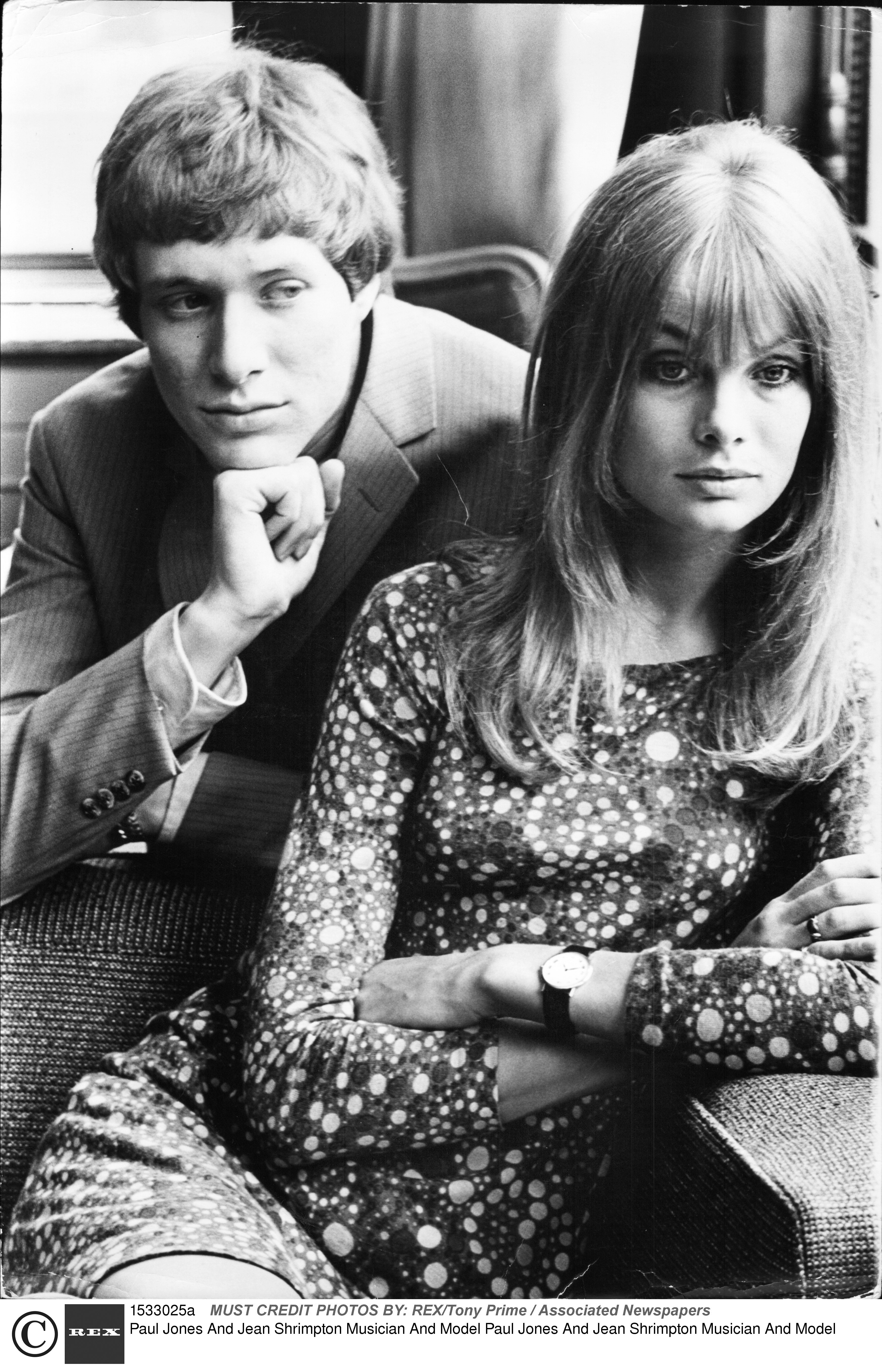

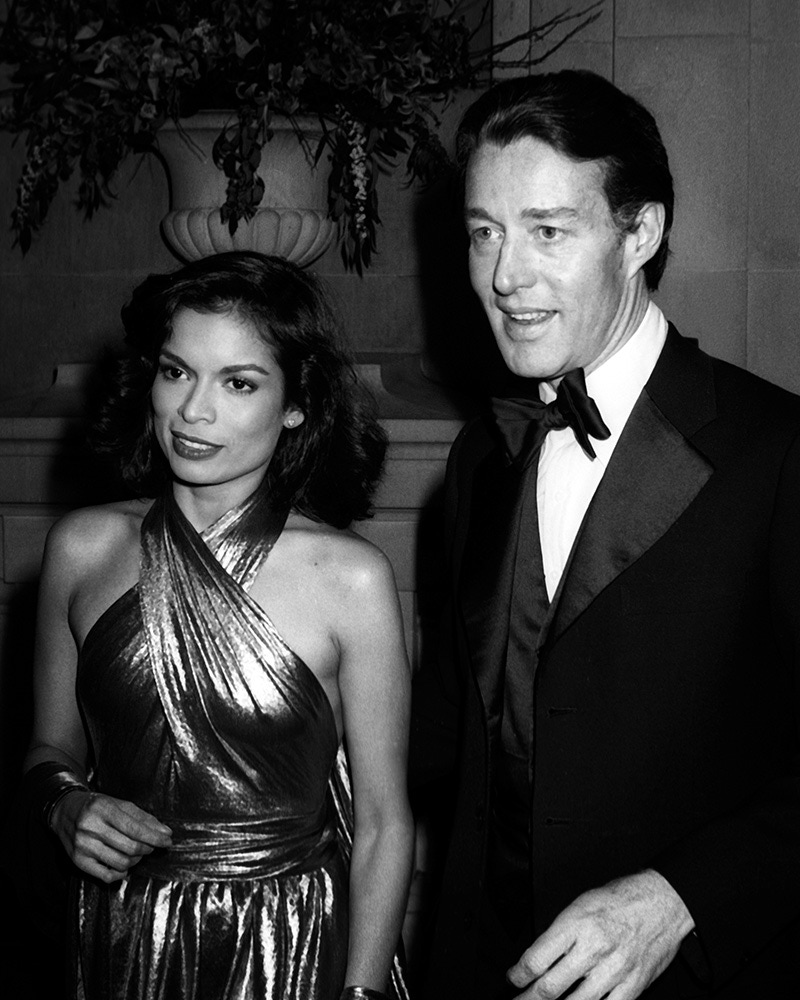

This is true not just of models. Sixties style was shaped as much by models like Jean Shrimpton and Twiggy, as it was by rock-god muses like Anita Pallenberg, Marianne Faithfull, Françoise Hardy and Jane Birkin. Bianca Jagger and Jerry Hall had more than Mick in common—Halstonettes who danced the night away at Studio54, they epitomised ’70s glam alongside ‘the fresh American face of fashion’, Lauren Hutton. The ’80s were ruled by the glamazons also known as supermodels—Christy Turlington, Linda Evangelista, Naomi Campbell, Tatjana Patitz and Cindy Crawford became household names. Kate Moss is as ubiquitous today as she was in the ’90s. As for the first decade of the new millennium, social media and the meteoric rise of street-styleblogs have put the spotlight on fashion insiders like Carine Roitfeld, Giovanna Battaglia, Emmanuelle Alt and Gaia Repossi, women whose unique personal style have greatly helped promote the idea of individualism in appearance.

Wallis Simpson once said,“I’m not a beautiful woman.I’m nothing to look at, so the only thing I can do is dress better than anyone else.” Although it certainly never hurt, beauty is not necessarily a prerequisite for becoming a muse. Through sheer force of personality and their clout as opinion-makers, women like Iris Apfel, Anna Piaggi, Isabella Blow, Diana Vreeland and Eleanor Lambert are revered for their audacious sense of style.