The Style of the Olivier Awards

The Rake explores the red carpet style quirks seen at this year’s Olivier Awards, and considers why it's worth paying attention to them.

I much prefer the style of the Oliviers to the Baftas and the Oscars. Though the ceremony is more understated than it’s film related counterparts, from a sartorial perspective its far more curious – populated as it by those actors who have chosen to at least partially shun the silver screen and instead commit themselves to a life spent treading the boards, in pursuit of dramatic perfection. Clichéd though this might sound, there is most certainly a sense of theatricality about the tailoring on show, notably more so this time around than there has been before and from a position of complete ignorance, one can’t help but think rather romantically that the expressive nature of theatre performance lends itself to experimenting with the traditions of red carpet formalwear.

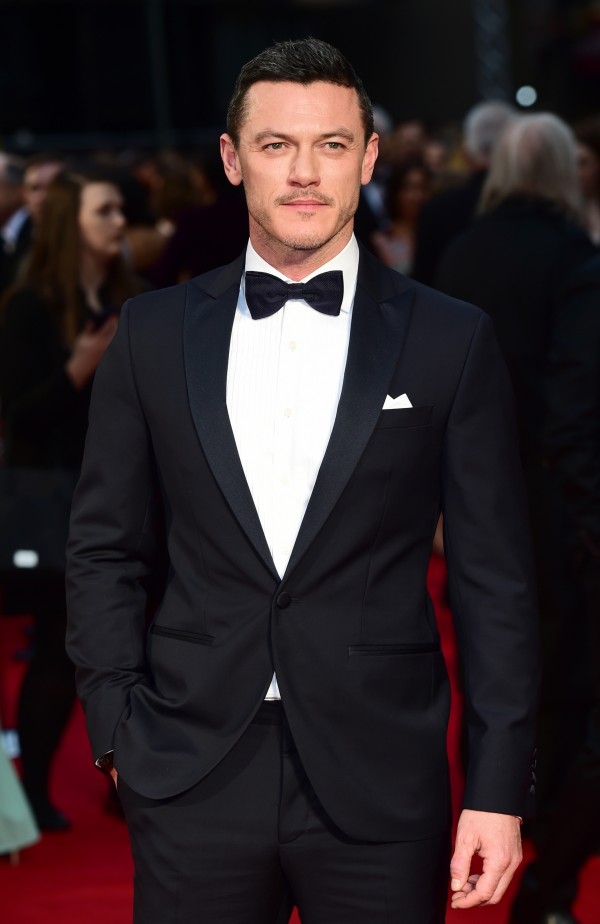

This year’s awards in particular presented a veritable raft of polished evening dress, with just about every variant of the dinner suit on display from the perfectly executed classic shawl or peak lapelled black two piece, to a number of slightly more outré, yet beguiling cocktail looks. Luke Evans in a slim, trim black two-piece dinner suit from Hackett looked rather fine. As did James Norton, who opted for a true midnight blue three piece, cut by contemporary British tailors par none, Thom Sweeney. Lent a natural suavity thanks to his suit’s well balanced lapels, smooth waist run and soft lines, Norton made a particularly elegant impression, thoroughly reinforcing the timeless appeal of midnight blue.

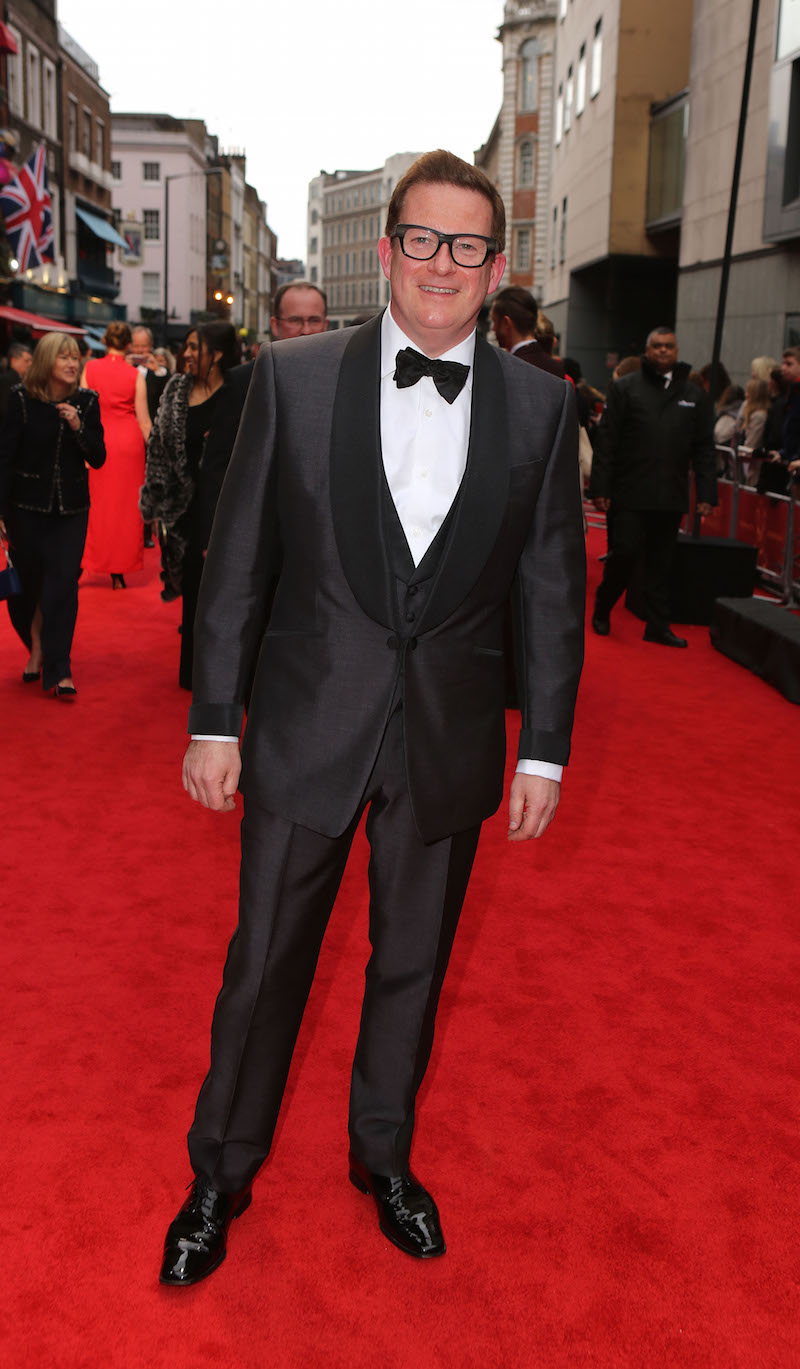

Many more perspicacious gentlemen, including winners of the award for Best Actor Kenneth Cranham, and Best Supporting Actor Mark Gatiss, displayed a similarly refined aesthetic; both in clean-cut coats paired with traditional white Marcella fronted dinner shirts. The devil here is very much in the details; Savile Row’s Chester Barrie cut both these suits and the coat’s fit and lines in both instances were crucial to the overall composition of each look. Both suits were ventless, as is traditional, helping each jacket’s skirt to hug the hips for a clean line, which was complimented by the fact that both coats fastened just below, rather than on or above the natural waist, for a louche attitude which also offers the added bonus of elongating the line of one's lapels. Both suits were faced not in grosgrain, but a rich Mogador twill, which whilst unorthodox, lent both garments an undeniably superior sheen and significant depth of texture. Pockets were bound in the same facing without flaps for a polished finish.

That’s classical black tie covered, but having sponsored the Oliviers for the past five years, Chester Barrie has also set a precedent for immaculately conceived yet unconventional red carpet attire, cocktail dress and comparatively contemporary, fluid eveningwear. For a lesson in modern dinner dress done well, one could refer to the exquisite French blue three-piece suit with full bellied lapels, turn-back cuffs and slanting jetted pockets worn by Rory Kinnear, which was paired with a powder blue voile pleated dress shirt. Alternatively one might reflect upon the sumptuous, smoky grey Loro Piana silk-cotton-cashmere velvet smoking jacket donned by David Gandy. Quite apart from the coat’s glorious sheen and the superior quality of the velvet itself, its exquisite ground mother of pearl buttons (which are made exclusively for Chester Barrie) the low-buttoning waist, heavily expressed chest and the rich belly on the coat’s shawl collar all channeled a touch of that retro glamour which the house is so well known for.

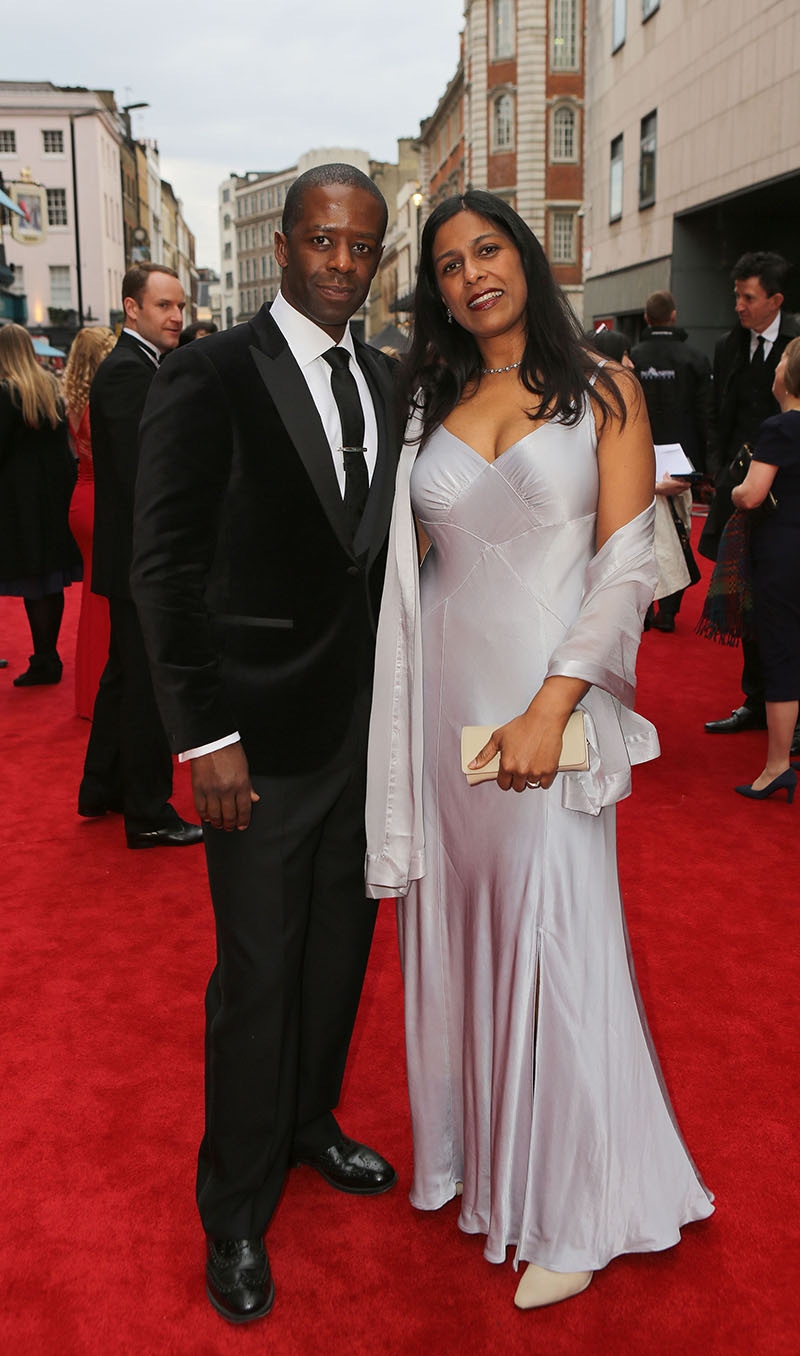

Ensembles like this reposition and contemporise black tie in fine style, without compromising on a sense of tradition or integrity. The most evolved take on this theme was another Chester Barrie look, Alfred Enoch’s fearlessly crisp claret mohair two piece suit with a burgundy velvet top-collar, which was much more a cocktail suit than a Tuxedo, with it’s long skirt and slim lapels. Nevertheless, this bold choice garnered a deserved amount of attention and when paired with a soft white evening shirt and classic black satin bow tie, all necessary conventions were observed with aplomb.

But why should we choose to dwell on the style of the Oliviers? Put simply, black tie is a difficult and mysterious dress code to either conform to, or experiment with successfully, so to witness an event where black tie is worn well en masse nowadays is a rarity. The Oliviers then, demonstrates the value of observing sartorial tradition; the aesthetic nuances affected by faced lapels, ventless coats, jetted pockets and piped trousers, but thanks to the work of tailors like Chester Barrie, it also offers a lesson in how to manipulate and even transcend tradition; experimenting with blue or burgundy mohair, velvet, low-fastening coats, slanting pockets, the expression of a jacket's chest or skirt and so on.

It’s a subject that The Rake is going to be exploring in more depth over the next couple of weeks, and with this in mind, we wholeheartedly suggest that the Oliviers should be the starting point for all those thinking of exploring the expressive possibilities of the dress code this season.