Paul Robeson: THE TRAILBLAZER

Paul Robeson was the son of a former slave whose life was marked by tragedy, triumph and tribulation. Now a new biopic by Steve McQueen aims to restore his prominence in social and political folklore.

“The best-known American in the world”, was how Paul Robeson was described without irony or argument by a journalist in 1964. Yet today, among the Instagram generation, his name is mostly forgotten. That is set to change, as the Academy Award-winning director Steve McQueen has announced plans to bring Robeson’s story to the screen. It is perhaps fitting that cinema, a medium in which Robeson excelled, will restore his renown as a cultural monolith and social justice campaigner.

Paul Leroy Robeson was born in April 1898 in Princeton, New Jersey — a town known more for its redbrick university than the realities of its stark income divide. His father, William Drew Robeson, was an escaped slave who became a Presbyterian minister, while his mother, Maria Louisa Bustill Robeson, was a Quaker schoolteacher, originally from Philadelphia. But childhood happiness quickly faded: when Robeson was six, his mother’s dress caught fire and she died. The childhood loss left him bereft and perhaps forever seeking female warmth.

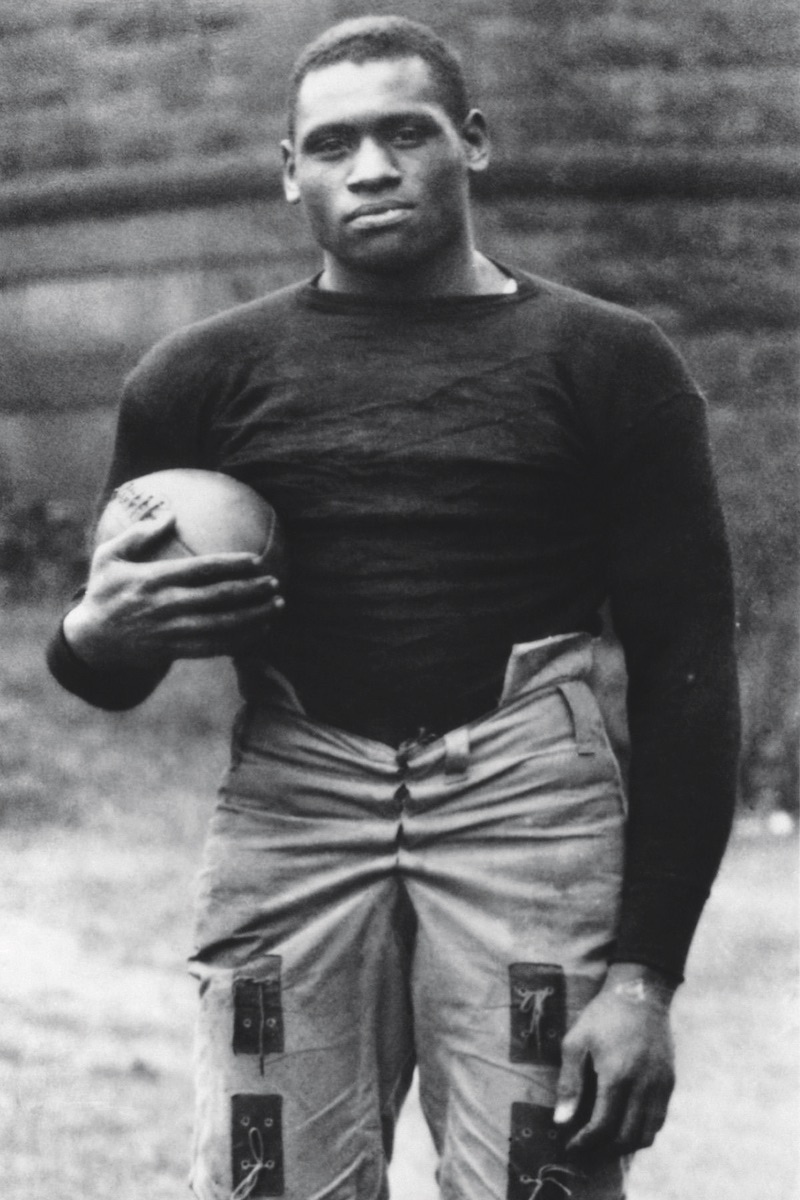

At 17 Robeson earned a scholarship to attend Rutgers, a leading university in New Jersey. Only the third African American to be admitted, he went on to become one of the institution’s most distinguished pupils. So decorated is his C.V. that if he were a character on screen or in fiction, you’d cringe at the writer’s bloated and unrealistic depiction. But of Robeson, it is all true. He was arguably the greatest American footballer of his generation; he played basketball professionally; and he was seriously considered as a contender to fight Jack Dempsey, who at the time was the world heavyweight champion. He was suave and charismatic with Ken-doll proportions. Robeson could sing in more than 20 languages, including Russian, Chinese, Yiddish, and a number of African dialects. Upon graduation he won 15 letters in four varsity sports, was elected Phi Beta Kappa — the oldest and most prestigious American academic honour — and, the prized orator he was, led his class with the final address as valedictorian.

But this achievement was not without sacrifice. On the football field — a typically sacred space of all-American-male camaraderie — Robeson was terrorised by his own teammates. He had his shoulder dislocated, his fingernails ripped off, and his nose broken. Stoicism and resilience was his father’s stance on the matter. “I had to show that I could take whatever they handed out… This was part of our struggle,” Robeson revealed in historian Sterling Stuckey’s book Going Through the Storm: the Influence of African American Art in History.

After graduating, Robeson attended Columbia University’s law school, teaching Latin and playing professional football on weekends to pay for his tuition. It was here that he met Eslanda ‘Essie’ Goode, a promising chemistry student whom he quickly married. They were an unlikely pair in many ways: Robeson was literary and creative while Goode preferred numbers and science labs. She was precise; he was convivial; he thrived at night and she preferred the early mornings. But they stuck, and it was Goode who coaxed him onto the stage — and ultimately became his manager — after he encountered crippling racism at his first post-Columbia firm.

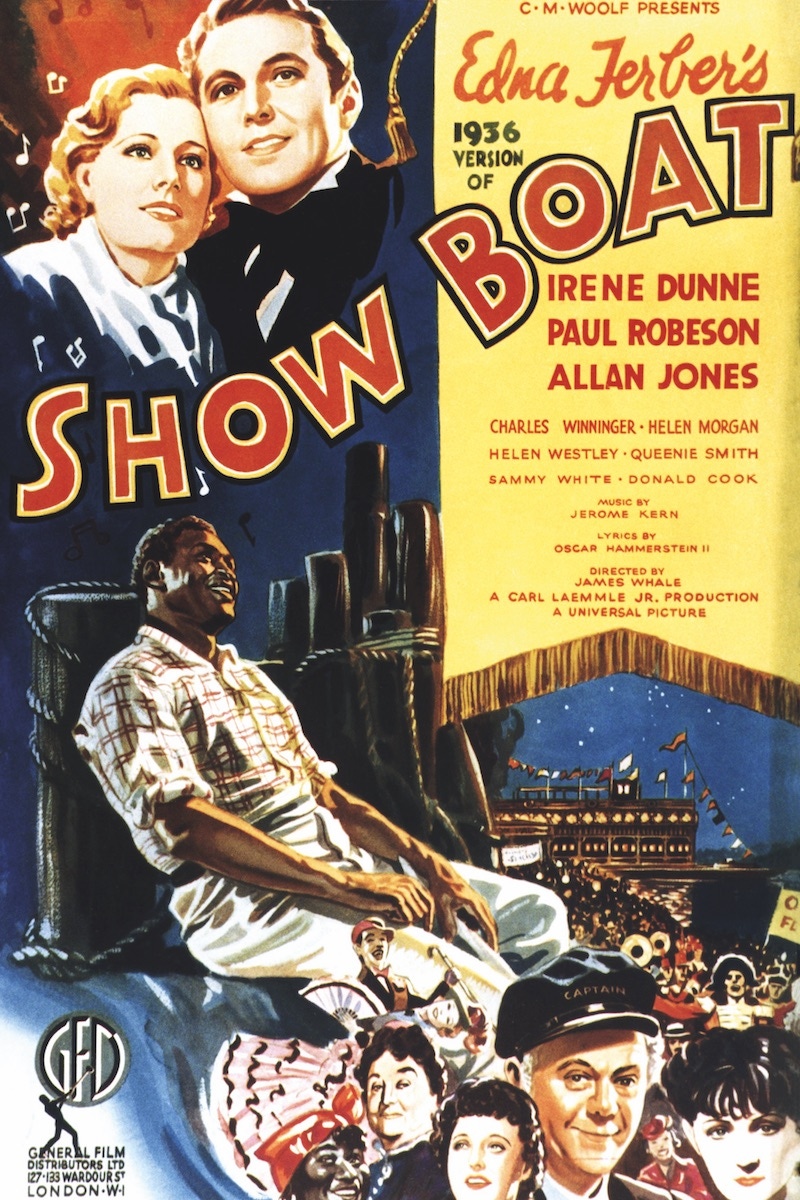

On stage, as he would have been in the courtroom, Robeson was a forerunner. In most instances he was the first, and only, black man offered serious roles in otherwise all-white productions. Lasting for nearly 300 performances, his Othello was the longest-running Shakespeare play in Broadway history. Not only did he act, but Robeson sang, gloriously — his best-known performance was Ol’ Man River from Show Boat, a courageous and controversial musical that took on racism and segregation in the Deep South. With his velvety vocals he commanded a room, on and offstage, and was befriended by a host of prestigious personalities, including Eleanor Roosevelt, W.E.B. Du Bois, Joe Louis, Pablo Neruda, Lena Horne and Harry Truman.

Robeson possessed an ineffable quality, as is the case with many individuals of talent. At all times he was perfectly turned out — typically in a three-piece suit — but that was almost secondary because he looked great no matter what. Robeson wore his clothes; they never wore him.

Read the full Paul Robeson story in Issue 70 of The Rake - on newsstands now.

Subscribe and buy single issues here.