Abstract Expressionism at the Royal Academy of Arts

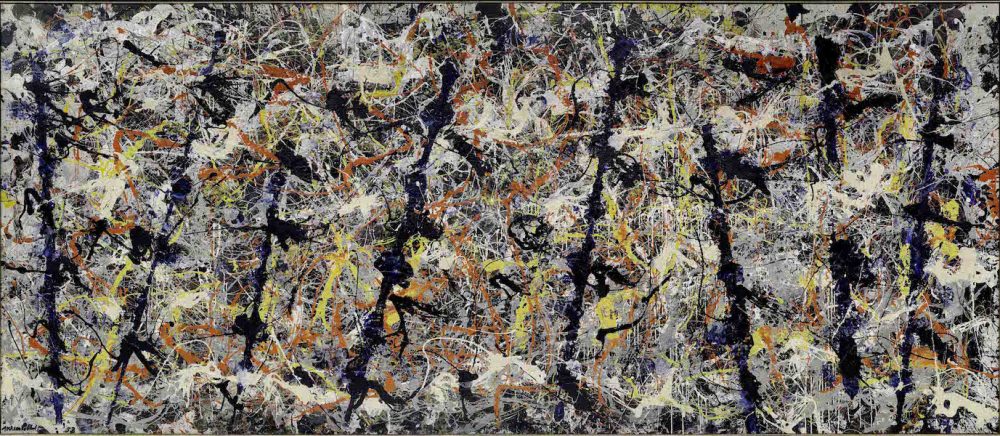

In the 1940s, Abstract Expressionism exploded in similar fashion to the way in which Jackson Pollock, a vanguard of the movement, would energetically yet thoughtfully splatter paint in a sporadic and generous manner onto his outstretched canvas. It was a cultural phenomenon, a rebellious act that vented the inner and broader societal frustrations. Yet although this occurred nearly 80 years ago, it still to this day remains utterly relevant. Abstract Expressionism, which is currently on show at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, is a certainly a once-in-a-lifetime viewing experience (the last time an exhibition of this size happened in the UK was in 1959), and the overall curation of the spectacle is so on-point, it will leave your brain perfectly scrambled as you exit back onto Piccadilly.

The breadth of this exhibition is quite astonishing. By this, I mean the expansive scope of the works on show with their eclectic spectrum of bright and visceral colours to neutral, dark and somber tones which you’re unwillingly absorbed by. The variety of mediums; painting, sculpture, photography and prints — and of course, the highly impressive list of great 20th century artists — all of which share a strand of DNA that’s riddled with such sheer complexity, you’re left stunned in the feat of trying to dissect their assemblage. For someone of my generation this is the first time I have seen such an expansive collection of Abstract Expressionist works in one go, whereas, a mature Rake reader might well differ. I’ve been fortunate enough to travel and visit museums and galleries, both in Europe and in America, but as exhibitions go in London this is without a doubt one of the most impressive exhibitions I have ever witnessed.

"It was a cultural phenomenon, a rebellious act that vented the inner and broader societal frustrations".

You’re first presented, in room one, with a selection of small-scale works from the late 30s and early 40s which are in contrast to what many people visualise Abstract Expressionism to be; large scale canvases, strewn with vibrant and energetic flows of colour straight from the subconscious. Self-portraits by the likes of Pollock and De Kooning (who headline the show, in addition to Rothko) offer an insight into the early stages of the movement and reveal the influence that European art movements such as Surrealism and Cubism had on Abstract Expressionism. This then leads to room two which features the work of Arshile Gorky, a migrant from Armenia who moved to America following the Armenian Genocide. The collection, in addition to the former room, reflect the basis of inspiration — European modernism. But it’s important to note that although Abstract Expressionism is undeniably an American creation, its forebears came from across the globe, many fleeing the atrocities that plagued Europe in the 1940s, which consequently played into the subconscious of the artists’ aesthetic.

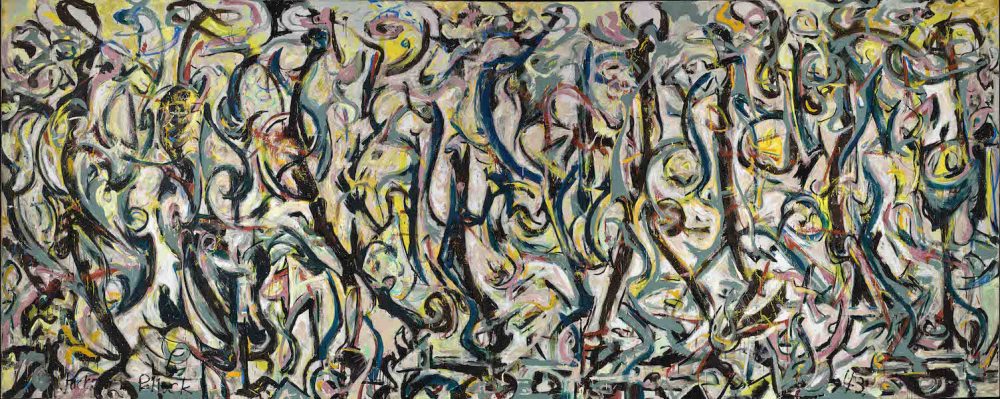

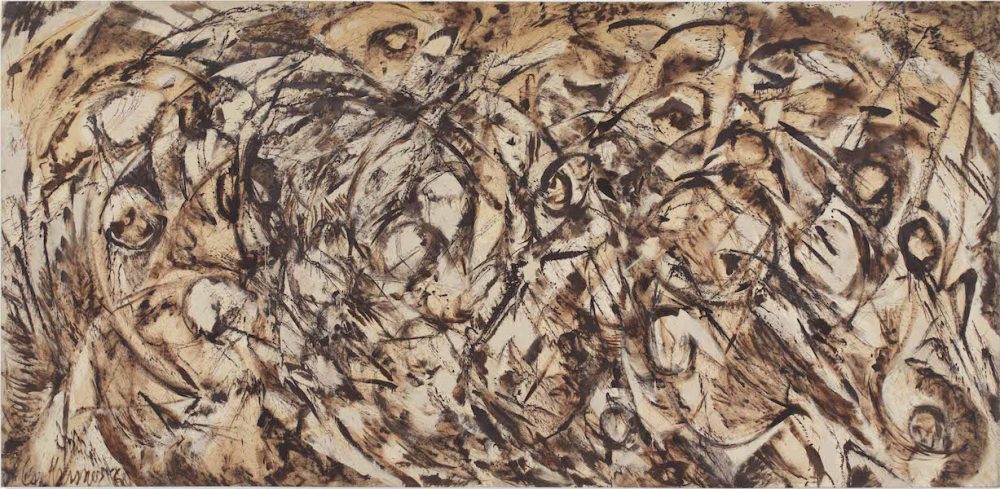

As aforementioned, Jackson Pollock steals the show. But what astonished me most was that although certain works of his are engulfing in their magnitude — such as Mural (1946), which was commissioned by Peggy Guggenheim, and is his largest work ever completed, and Blue Poles (1952), together the two works are the most heralded — a large proportion of works on show are of manageable and easy-transportable size. Pollock’s genius mixed with his inner troubles — he was a chronic alcoholic which led to his quasi-suicidal death from a car crash, symptomatic of an artist who grew up during the Great Depression — is thoroughly evident through his subconscious-energetic-expressions. The Pollock room seems by far the most popular with exhibition dwellers, yet there is no typical goer at Abstract Expressionism. That’s another reason why it’s so great and the wide demographic only speaks of the movements magnitude.

The exhibition then proceeds through a handful of rooms that are dedicated to singular artists (some lesser known) and themes. Whilst they don’t have the same ‘wow’ factor as the likes of Pollock and Rothko, they’re still intrinsic to the overall understanding of the movement and its wide range of styles and themes. One artist who I was unaware of is Franz Kline. Kline’s large white primed canvases are finished with passionate black brush strokes urging you to be able to understand the source of it all. It’s no surprise that he is known for his two-tone work, its simplicity and lack of colour is captivating.

As you wonder through the rooms, Willem De Kooning’s violent work suddenly jumps out at you. Women played a major role in his style of work, but the way they’re portrayed is awesome in its harrowing effect. Reflecting on the role of the female form, De Kooning once said: “I see the horror in them now, but I didn't mean it. I wanted them to be funny… so I made them satiric and monstrous, like sibyls.” From De Kooning you’re lead into the RA’s main room where six Rothko’s fill the walls. The room is dimly lit (Rothko insisted that when he died his work was displayed in near-darkness) and the bottom of the canvasses are a mere couple of feet off the ground. Rothko’s saturated-colour fields somehow warm the room and draw you inwards. It’s an unforgettable experience, whilst whispers of marvel provide the soundtrack.

Whilst the headliners steal the show, with their imagery forever engraved in your memory, the rest of the exhibition’s purpose serves to show the extent of its breadth, and examines the work of less-known artists. The thread that ran through the Abstract Expressionist was that they were all friends who were dependant on one another. Their work was so avant-garde — breaking social and cultural contexts, it was damned to fail. The spirit between them is so commendable, it’s unlike any other movement that’s followed or preceded it, and in many a way rakish in its social structure. The simple fact that this scale of an exhibition hasn't happened in the UK for almost 60 years should warrant enough to go, but the feelings you get whilst peering at a Rothko, or into a tangled Pollock, are almost unexplainable despite there being an infinite amount of adjectives to describe Abstract Expressionism.