George Petty and The Pin-Up Girl

In times of hard porn on keyboard tap, in an age in which the erotic has been subsumed by the gynecological, it is sometimes difficult to picture the gently titillating being the product of pencil and paper. But back when more graphic stuff was printed but still considered strictly outre - brown paper-wrapped and from under the counter, if you knew where the counter was - artist George Petty helped define the American notion of sexy.

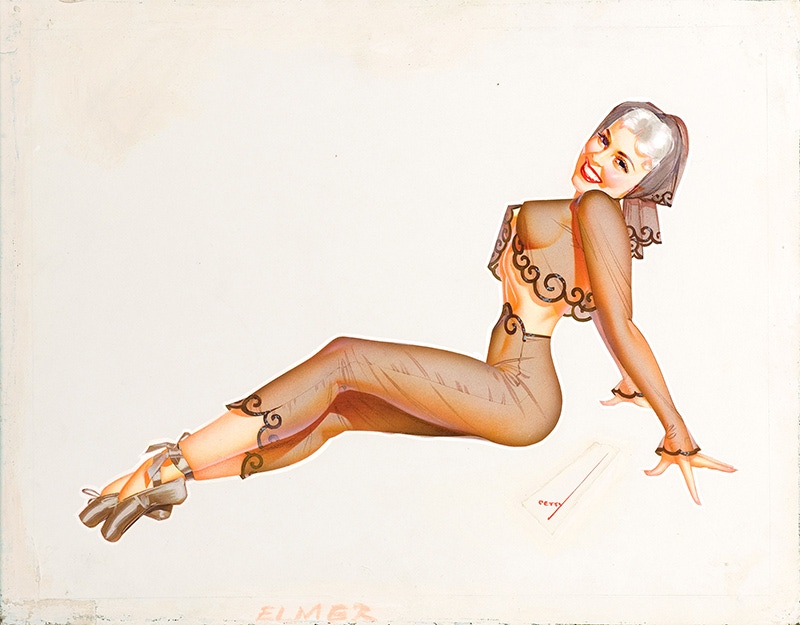

All curves and smiles, what was known as his ‘Petty Girl’ could be prim and playful, barely dressed and yet barely aware of the fact, or dressed up - for healthy sports, a swanky evening, as a cook, matador, cowgirl, even as Santa if it was the right time of year. She was less the man-eater and more the girl next door of your dreams, all the more arresting for her modesty. She spent a lot of time on the phone - just who was she talking to? - or awkwardly getting her skirt caught on a fence or fishing rod line. And she was born 90 years ago this year, when her creator opened his first studio. Within seven years she had become a staple of American ‘Esquire’, setting her on the way to becoming iconic - appearing on matchbooks and mugs, playing cards and bonnet ornaments, in special incarnations to promote everything from cigarettes to power tools - but also symbolic.

Petty was not Alberto Vargas, the illustrator whose work most often springs to mind when one one thinks of pin-up girls - which, if you’re adolescent or easily distracted, could be much of the time. But timing was on his side. Working at his prime through the 1940s and 1950s, Petty’s version of womanhood was not only all together more real - he worked from life models, but, as Hasbro would do with the Barbie doll, would typically extend the length of their limbs a touch for added litheness - but all the more sentimental.

World War Two sent many young American men away from their homes and sweethearts, and if they didn’t have a sweetheart, from the prospect of getting one. The Petty Girl was a lifeline: back to their small town lives, back to their stalled sexuality of course - contained as far as the military could manage - but also back to an innocence which war was certainly at odds. It was the Petty Girl US Army Air Force bomber crews mimicked in the curvaceous talismans they painted on the nose cones of their Liberators and Flying Fortresses. The bathing beauty on the famed ‘Memphis Belle’ B-17 was a straight copy of a Petty girl of 1941, selected by Petty himself at the request of Robert Morgan, the bomber’s pilot.

Certainly, while Petty had serious artistic inclinations - his father, George Petty III was a photographer, and Petty would go on to study at the prestigious Academie Julian in Paris, heading back to his native Chicago at the outbreak of World War One - he also intuitively understood the reach of what was, in the 1930s, a new media, the men’s magazine market. While he had drawn and airbrushed his girls for commercial purposes through the late 1920s, it was only when he joined ‘Esquire’ in 1933 that the Petty Girl became a national phenomenon.

Here were illustrated women who, while obviously targeted at men - Petty’s idea that his illustrations be positioned in the middle spreads of the magazine gave rise to the term ‘centre-fold’ - still managed to appeal to women viewers too, such that swimsuits and underwear were marketed using the Petty Girl name and imagery. Her ease and domesticity perhaps was more wholesome than threatening, a reminder of happier times, before the war, before the Great Depression. Few could be coaxed into a grin by her, all the more so given the kind of typical accompanying caption: “My talent can’t compare with Titian’s / Yet they say my composition’s / Rather bold, my tones are warm / And critics praise my line and form,” goes the ditty aside a 1955 girl dressed in beret and transparent artists’s smock, holding brush and palette.

Such was the success of this careful pitch between revealing and hiding, fantasy and fun that when, during the 1940s, Petty left ‘Esquire’ over a pay dispute, his replacement, one Alberto Vargas, was instructed to echo Petty’s style. Such was the Petty Girl’s success, indeed, that one Hugh Hefner saw an opportunity to sell a photographic take on her - his Playboy Bunny, of course, once similarly accessible and restrained before the culture shifted towards a demand for ever more exposed flesh.

Would Petty have approved of this? By the time he died, in 1975, having drawn his last, by then rather quaint girl just a short while previously, the relative chastity of the pin-up’s golden age was already long gone, only to be rediscovered decades later by the retro-fueled combination of vintage fashion and contemporary tattooing. But perhaps even the utterly sexually liberated can’t help but imagine that Petty’s more tantalising less-is-more approach might prove a welcome corrective to the numbing excesses that have followed.