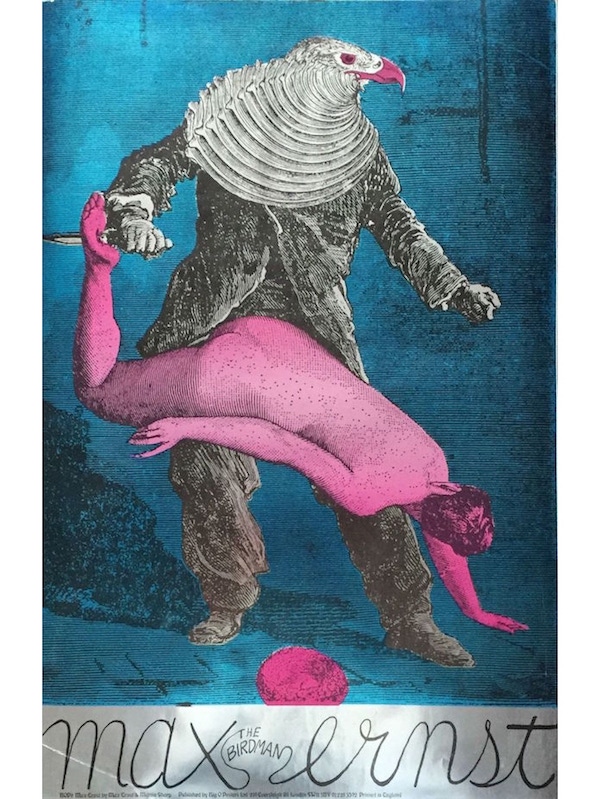

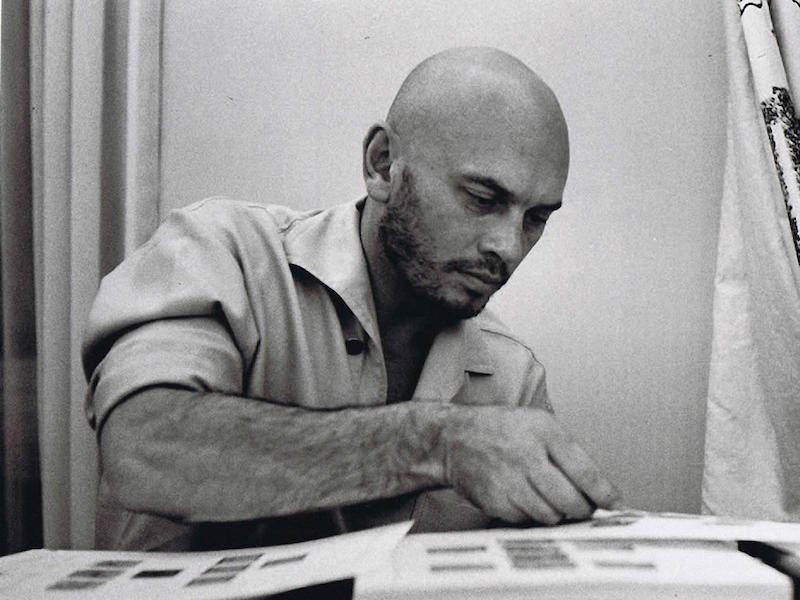

Martin Sharp: Art as Pop, Pop as Art

Australia’s greatest psychedelic pop purveyor occupied the space between sound and vision, sacred and profane, art and design.

In 1965, author William S Burroughs remarked, “I see no reason why the artistic world can’t absolutely merge with Madison Avenue. Pop art is a move in that direction. Why can’t we have advertisements with beautiful words and beautiful images?” Although he never went to work for an ad agency, iconic Australian psychedelic pop artist Martin Sharp — like his contemporary, Andy Warhol — certainly broke down the barriers between media, marketing and packaging design, with much of his most memorable work not adorning gallery walls, but instead, magazine covers, record sleeves and posters.

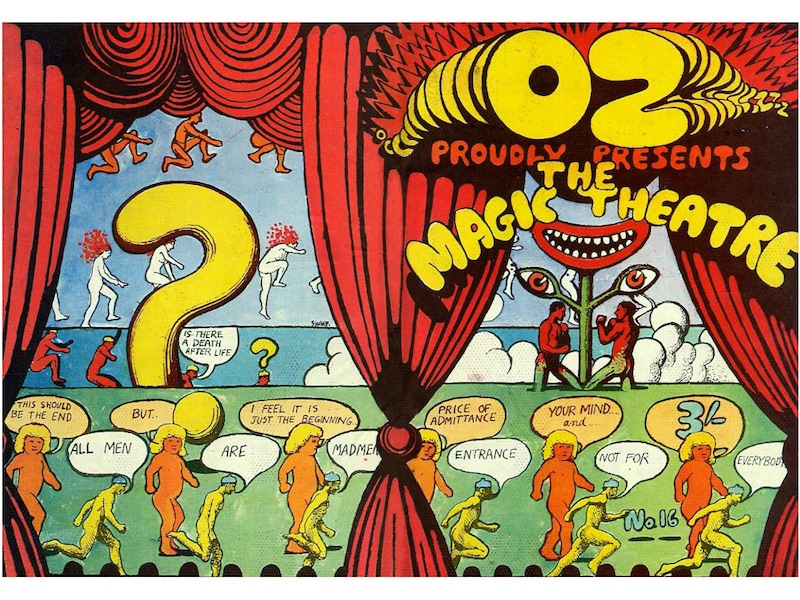

Brought up in a wealthy family, attending the exclusive Cranbrook school in Sydney’s leafy Bellevue Hill, while at art college in the early sixties Sharp fell in with writer Richard Neville, the two soon collaborating on seminal countercultural magazine, Oz, where Sharp served as art director. The publication’s irreverent content — raunchy wordsmithery and imagery that thumbed its nose at authority and conservative good taste, while taking a stand against war, corruption, gender, sexual and racial discrimination — saw Sharp, Neville and his co-editor Richard Walsh twice charged with obscenity, narrowly escaping jail and quickly beating a retreat down the hippie trail to ‘Swinging London’.

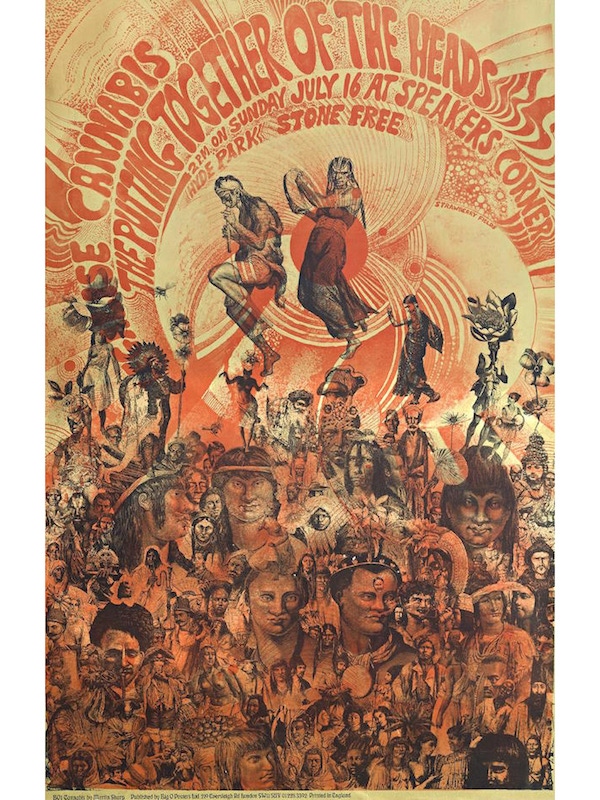

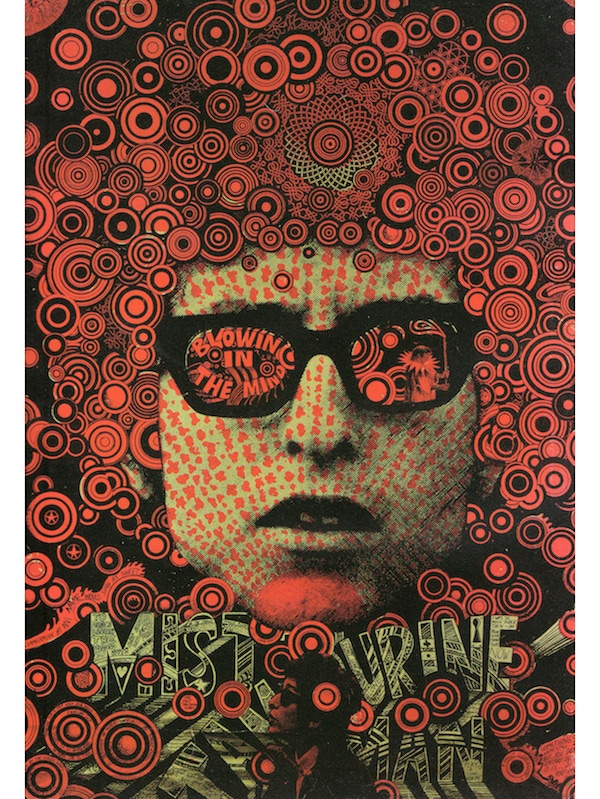

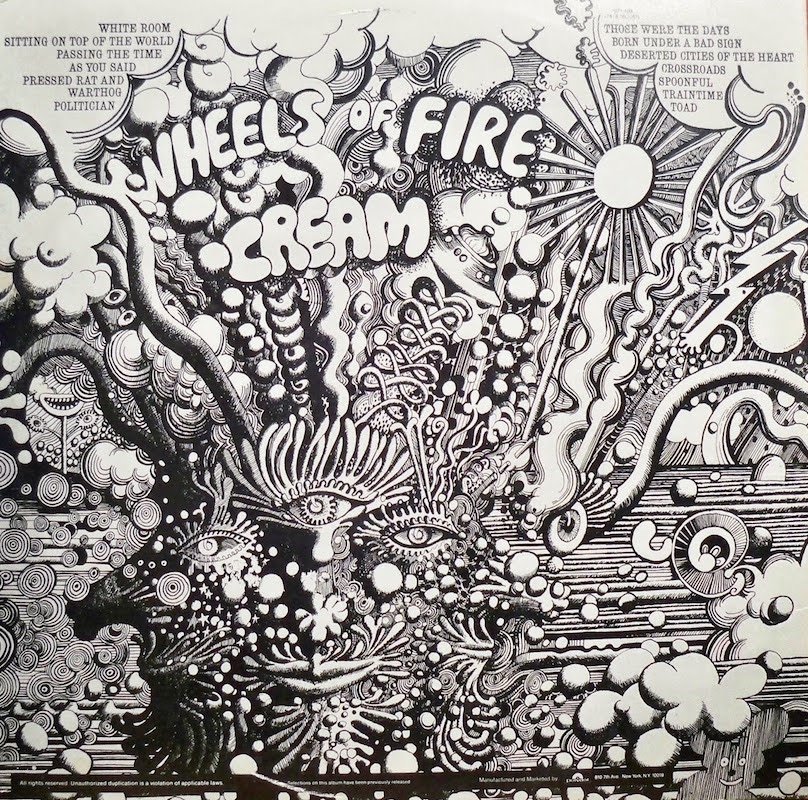

"Much of his most memorable work did not adorn gallery walls, but instead, magazine covers, record sleeves and posters."There, Sharp happened to meet a young guitarist named Eric Clapton, who mentioned he was in need of lyrics to accompany a tune he’d composed. The Australian artist jotted down some poetry on a napkin — which Clapton in short order recorded as ‘Tales of Brave Ulysses’, the B-side to his band Cream’s smash hit, ‘Strange Brew’. Clapton then commissioned Sharp to design the trippily illustrated cover for Cream’s LP Disraeli Gears, the two by this point cohabitating at Kings Road artists’ commune, The Pheasantry (alongside fellow contemporary cultural figures including writers Germaine Greer and Anthony Haden-Guest, and top rock photographer Robert Whitaker). Sharp won the New York Art Director’s Prize for his design of Cream’s third album, 1968’s Wheels of Fire, that same year finding the musical muse he’d be inspired by for the remainder of his days, eccentric American minstrel Tiny Tim. Sharp’s imagery for the falsetto-wailing ukulele stylist remains among his best-known work, alongside the seminal psychedelic rock posters he created around this time for acts including Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan and Donovan, which to this day are hallucinogenic staples on smoked-out students’ walls the world over.

Meeting up with his old partner in crime again in London, Sharp had recommenced his collaboration with Richard Neville, the duo — along with fellow Aussie expat Jim Anderson — launching a British edition of Oz in 1967, taking advantage of the superior printing available in London (as opposed to the comparatively primitive facilities accessible back home in ‘the colonies’) to seriously push the boundaries of magazine craft. Issues of the UK edition of Oz would feature then-cutting-edge novelties such as metallic foiling, fluorescent ink, adhesive stickers and pull-out posters. The publication became renowned globally as among the most forward-thinking, creative publications around, and copies from this period now shift for substantial sums on eBay.

Sharp had turned off and dropped out of Oz by the time it again fell afoul of the law, his replacement on the masthead, Felix Dennis (who’d go on make a fortune as the publisher of Maxim, Blender, Stuff and The Week) facing British courts alongside Neville and Anderson in the infamous Oz trial of 1971, charged with “conspiracy to corrupt public morals” and facing a potential life sentence over an X-rated issue of the magazine guest-edited by English school kids.

"The publication became renowned globally as among the most forward-thinking, creative publications around."The three were convicted on lesser charges and briefly jailed, but publicity resulting from the trial — and widespread grassroots yoof support for the embattled free-speech advocates — saw Oz’s circulation reach its highest ever level shortly after they’d been released and recommenced publishing. The magazine survived another couple of years, before Neville, Anderson and Dennis split to do their own thing, man. (In the latter’s case, this involved becoming the famously debauched, crack-smoking, poetry-spouting publisher of what was for a time the world’s biggest men’s magazine — a vastly wealthy sybarite who’ll forever be remembered for the quote: “If it flies, floats or fornicates, always rent it — it’s cheaper in the long run.”) Sharp meanwhile returned to Australia in the seventies, proceeding to cement his reputation as the country’s pre-eminent pop artist, holding numerous exhibitions of his work on canvas while continuing to engage in a steady stream of carefully chosen commercial jobs — most notably as the house designer of (now, highly collectible) posters and promotional materials for the lauded Nimrod Theatre Company. He played a key role in protecting the historic Sydney harbourside fairground Luna Park (which features in some of his most iconic paintings) from redevelopment, and kept up his partnership with Tiny Tim, nearly sending himself bankrupt during the decade-long process of making a film on Tim’s life. “The meeting of musician and artist directly without intermediaries is, and always has and will be, a fruitful one,” said Sharp, who passed away in 2013. The legacy of his work — occupying the space between sound and vision, sacred and profane, art and design — serves as ample testament to that statement.