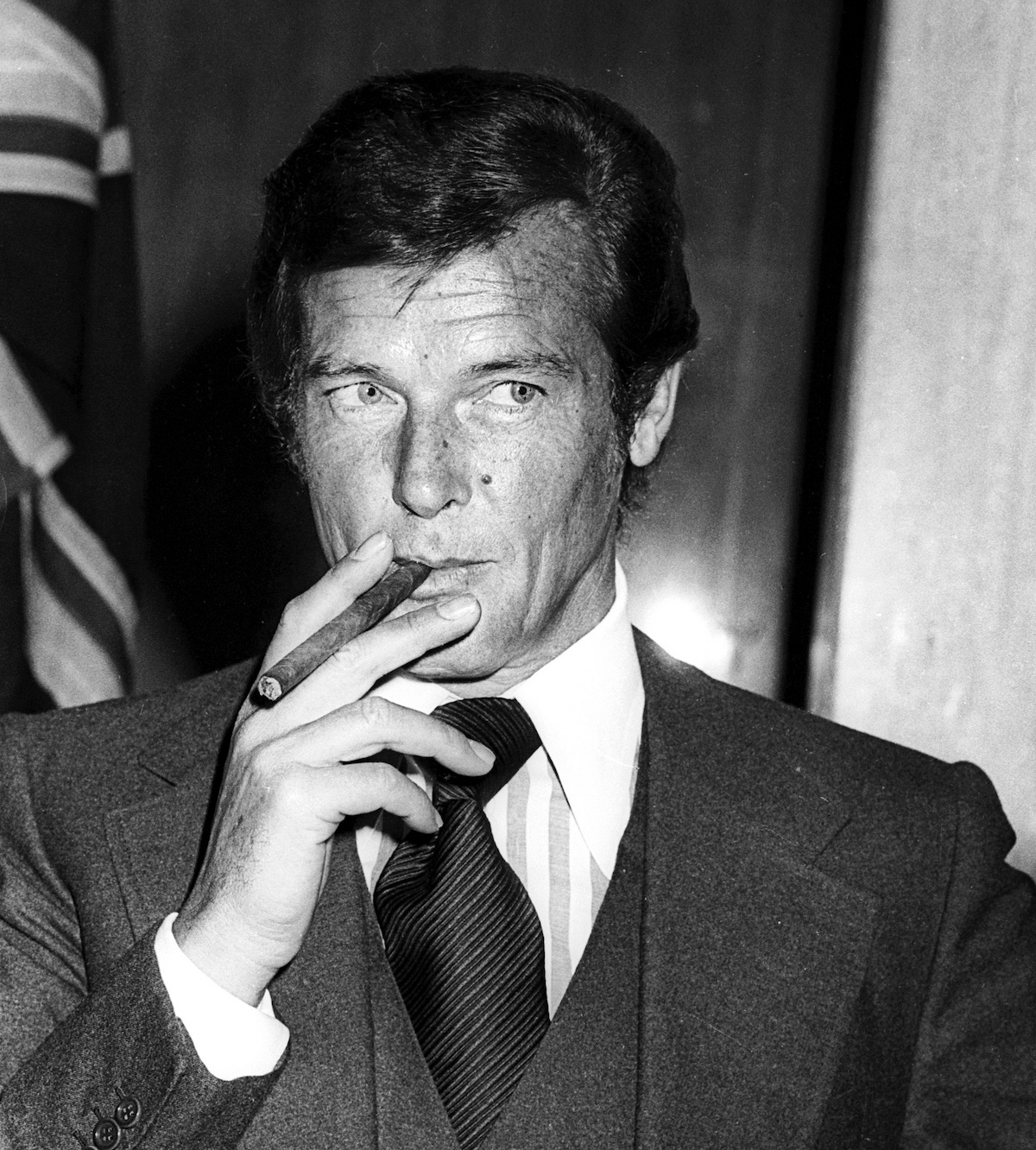

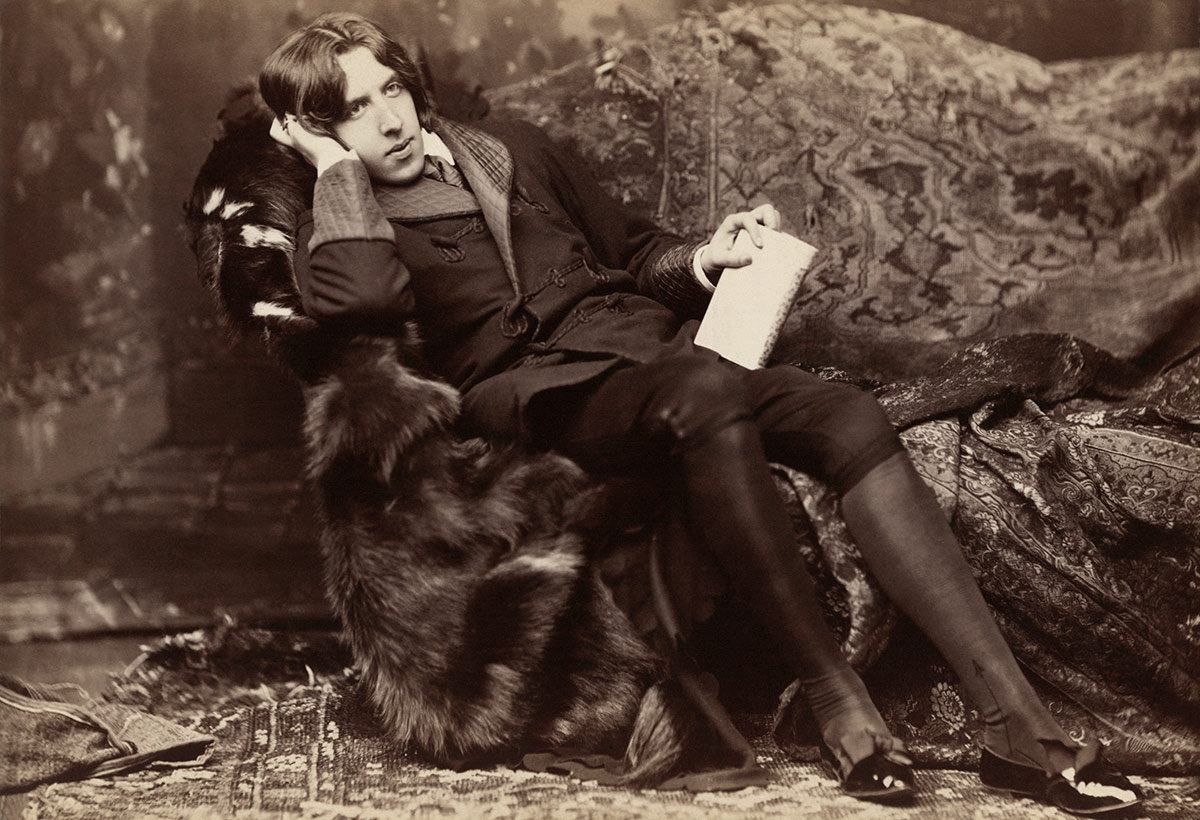

Oscar Wilde and the Joys of Smoking

In his account of the life and times of Oscar Wilde - which is witty and intelligent enough to match the man himself - Matthew Sturgis takes a look at the smoking habits of the 19th century's most renowned dandy.

‘Do you smoke?’ Lady Bracknell inquires sternly of Jack Worthing, in The Importance of Being Earnest, assessing his suitability as a suitor for her daughter’s hand.

‘Well, yes,’ he replies. ‘I must admit I smoke.’

‘I am glad to hear it,’ Lady B rejoins. ‘A man should always have an occupation of some kind. There are far too many idle young men in London as it is.’

Wilde, himself, was certainly not idle when it came to smoking. He recognised that, like all pleasures, it was something to be taken seriously. He devoted time, money and wit to matter. And, indeed, his whole career – from early promise, through initial frustrations, eventual success, and disastrous fall, to unchastened exile and early death – has to be followed through clouds of smoke.

He seems to have discovered the joys of tobacco as an undergraduate at Oxford. His boarding school in Ireland had been fiercely anti-smoking, even going to the length of printing ‘pledge’ cards for the pupils, stating: ‘I faithfully promise that as long as I am a Pupil at Portora, I shall never Smoke.’ Wilde’s Oxford contemporaries, though, recalled how, at the jolly parties he hosted in his college rooms, he would provide not only bowls of punch but also ‘long churchwarden pipes with a brand of choice tobacco’. They stimulated both merriment and wit.

For Wilde, nothing was ever done by half measures. When one young friend excused himself for being a non-smoker with the observation that he was ‘missing thereby what was, no doubt, good in moderation’, Wilde corrected him: ‘Ah Badley, nothing is good in moderation. You cannot know the good in anything till you have torn the heart out of it by excess.’

Amongst the various tobacco products available to him – pipes, cigars, cigarettes – Wilde soon settled upon the last. Cigarettes were chic, modern, and relatively expensive. (‘Give me the luxuries, anyone can have the necessities' was one of Wilde’s enduring maxims.) They also did not last too long. ‘A cigarette,’ he would in due course declare, ‘is the type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite and it leaves one unsatisfied.’

His friends describe him, when in company, with a cigarette almost always in his hand. He would light one, take only a few drags and then discard it, before – moments later – lighting another. Like many late 19th-century cigarette smokers, he does not seem to have inhaled.

One of the earliest of his sayings to be repeated in the press concerned the pleasures of smoking, and the irritation of having to wait until after dinner, before one could light up of an evening. At a London society dinner party, the hostess lamented to him that the wick of one of the lamps on the dining table had been ‘smoking all evening’. ‘Happy lamp,’ Wilde answered gravely.

Wilde came to favour Turkish tobacco, with its rich sun-dried aroma and mild flavour. One of the small vexations of his year-long lecture tour of America in 1882, was that he soon ran through his supply of Turkish cigarettes and had to fall back on the lesser pleasures of American tobacco. He came to favour a brand called ‘Old Judge’ – although a San Franciscan tobacconist paid him the compliment of mixing up a special blend called ‘Oscar Wilde’.

Wilde, throughout his life, ran up huge bills with his tobacconists. And did not always pay them. During his brief stint as editor of the Woman’s World, in the late 1880s, he greatly impressed one of his colleagues, first by smoking ‘wonderful,’ and very expensive, cigarettes, and then by declaring, ‘I can only afford them when I am in debt.’

Having achieved his first great commercial success in 1892 with Lady Windermere’s Fan, Wilde’s consumption became even more conspicuous, though his habit of not paying his tradesmen remained unchanged. He opened an account with the fashionable St James’s Street tobacconist, Robert Lewis (now J.J. Fox Cigar Merchants), and began ordering bespoke gold-tipped cigarettes, embossed with his name. Very typically, though, he matched his own extravagant self-indulgence with generosity to others. Sending his rather less successful brother, Willie, a cheque, he remarked, ‘Charming people should smoke gold-tipped cigarettes or die, so I enclose you a small piece of paper, for which reckless bankers may give you gold, as I don’t want you to die.’

Wilde recognised, though, that a cigarette was not just for smoking. It could serve as a useful prop: to punctuate a sentence or mark a moment. When faced by an importunate New York reporter asking unwelcome questions about an incident in which he had nearly been fleeced by a gang of con-artists, Wilde gained time by taking a very long drag, and an equally long exhalation, before answering cryptically, ‘I should object to losing $1,000, but I should not object to have it known if I had done so.’ The French writer Leon Daudet recorded how Wilde would always literally point out the incidents of his spoken stories and parables with his cigarette. In telling of the Fisherman and the Mermaid, for instance, ‘as he pronounced the word “sirène,” he raised his left hand up even with his right, which was holding his cigarette, and blew the smoke between them.’ The effect was mesmerising.

Scarcely less mesmerising was the practice Wilde instituted amongst his young male friends and lovers. If anyone asked for a cigarette, the giver would light it himself, take a preliminary drag, and only then pass it over to the recipient. The young Parisian poet, Pierre Louÿs, thought the custom touched with poetry. Others were less sure.

Cigarettes, certainly, possessed the power to shock, as Wilde well knew. He would, however, be both bemused and amused at the modern demonisation of smoking. Indeed, when being shown over the Cincinnati School of Design in 1882, he was amazed to see a large ‘No Smoking’ sign. ‘Great heaven,’ he exclaimed, ‘they speak of smoking as if it were a crime. I wonder they do not caution the students not to murder each other on the landings.’ In England, disapproval tended to be rather more oblique.

At the First Night of Lady Windermere’s Fan, Wilde found himself called on to the stage by the enthusiastic audience at the end of the piece. He made his bow but was immediately called back for a second. He reappeared, this time holding a lighted cigarette, from which he took the occasional nervous puff, while delivering a brief impromptu speech. It ended with the neat observation, ‘I think that you have enjoyed the performance as much as I have, and I am pleased to believe that you like the piece almost as much as I do myself.’

Although the audience greatly enjoyed the moment, some sections of the press appeared to be shocked not just by the brazen self-assertion of Wilde’s closing remark, but also by his appearing in public smoking a cigarette. It was, they claimed, both an affectation and an impertinence. Wilde was condemned by Punch as ‘quite too-too puff-ickly precious.’ And the idea that he always had a cigarette in his hand became firmly established in the public mind. Most of the caricatures made of Wilde during the 1890s depict him so. And the trope has been continued. When Maggie Hambling created her bronze sculpture of Wilde, for the Strand, in 1998, she ensured that it was holding a bronze cigarette. (The item, however, has been stolen so repeatedly that they have, sadly, ceased to replace it.)

If Wilde enjoyed smoking, he enjoyed too all the paraphernalia associated with it. Many of the journalists who interviewed him during his American tour noted his elegant amber cigarette-holder. And in an age when cigarettes were sold loose, he recognised the virtues of a handsome cigarette case. And the dangers too.

The comic action of his last play, The Importance of Being Earnest, is set in motion when Algernon reads a puzzling inscription in the cigarette case of his friend Jack. ‘It is a very ungentlemanly thing to read a private cigarette case,’ Jack protests in vain. The comedy of this line had its tragic sequel later that year (1895) when Wilde’s own habit of giving expensively engraved silver cigarette cases to the young rent-boys and pick-ups with whom he slept, was exposed in court. It was part of the evidence used to incriminate him. ‘I have a great fancy for giving cigarette cases,’ Oscar protested - but in vain. The jury was not convinced. Convicted of gross indecency with the various recipients of the said cigarette cases, he was sentenced to two years hard labour.

Not the least of the hardships of prison life was the absence of tobacco. And not least of the consolations of Wilde’s last years of freedom and exile, was being able to smoke again. Unable to work in any sustained way, bereft of congenial company for long stretches of time, smoking, as Lady Bracknell would have recognised, gave him not merely a pleasure, but an occupation.

Matthew Sturgis is author of Oscar: A Life published by Head of Zeus 4th October in hardback RRP £25