Uncommon Scents: Oud Oil

The surprisingly sensual oud oil has made its way into many major perfumiers, and despite its rarity is a staple scent on many a gentleman's dressing table.

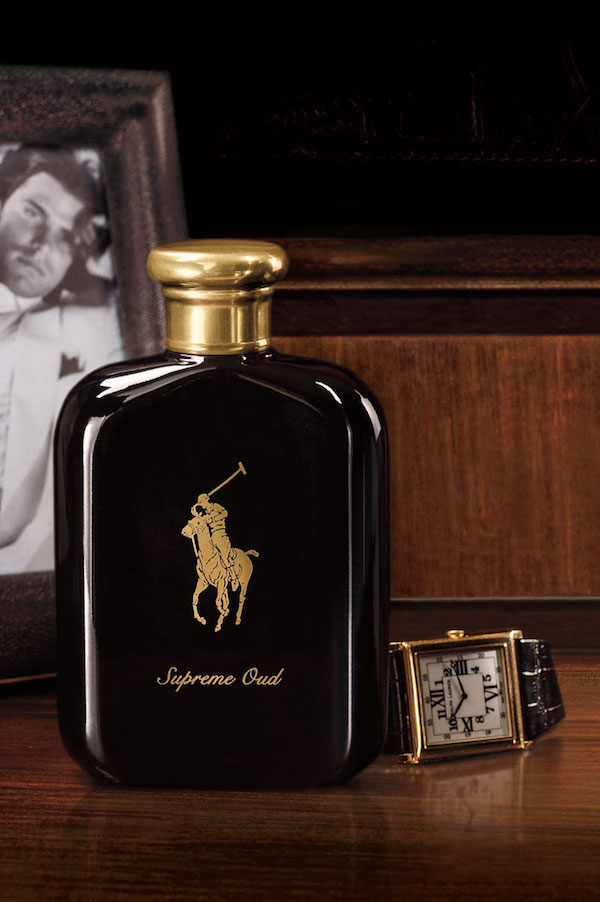

It’s an oil that is extracted from a thick, viscous black resin produced by a parasitic mould that infects aquilaria trees. It costs a fortune, at its best quality 1.5 times the price of gold. And if that wasn’t enough to put you off, to western noses at least, it smells awful - a blend of leather, wood, goat and old socks. And yet oud - the signature whiff of the Middle East for centuries - has become the defining ingredient of some of the most notable fragrances of the last few years: Tom Ford, Acqua di Parma, Calvin Klein, Dior, Armani, Van Cleef & Arpels are just some of the big names to have produced oud-based scents.

And that is all the more remarkable - global brands the likes of these typically have to strike a middle line to make the kind of sales the cost of their fragrance launches demand. Oud might be expected of more left-field fragrance houses the likes of Francis Kurkdjian, Kilian or Byredo - all of which have also used oud - but not of the more mainstream.

But oud, indeed, is the forerunner of a wider shift in thinking about fragrances: if the markets of the west have long been dominated by fresh, light, citrus-based scents - inoffensive, accessible, easy to wear, perhaps chiming with a rise in fixation on personal hygiene and a growing interest in the ‘natural’ - then recent times have seen an experimentation with ingredients that, on paper at least, would not be something anyone would want to walk into a lift wafting from their person. If certain fragrance companies, the likes of Demeter (with its Grass, and Gin & Tonic scents, for example) or Comme des Garcons (with its tar and sherbet-based ones), have pioneered the unusual for years - admired but rarely imitated - then their approach is rapidly becoming the new centre-ground.

In part this is a product of western ‘noses’ (as fragrance designers are called) opening their olfactory minds to the scents of faraway places - the likes of oud - with, as Demeter’s CEO Mark Crames notes, globalisation helping long cherished, but decidedly regional, tastes cross cultural barriers. But it’s also a product of competition: the mass-market fragrance industry has too long surfed on me-too products dependent less on inventiveness or originality as brand names and celebrity endorsement. More and more that’s a high risk strategy - these products might, literally, be on the shelves for a matter of weeks before being dropped.

Instead, fragrance houses are taking a new tack - seeking to stand out, especially to an ever more fragrance-literate consumer, with the fragrance itself, which is one reason why boutique fragrance houses are, at last, both proliferating and enjoying such boom times. The unexpected success of oud - and its subsequent widespread adoption - has, as the specialist dealer in rare fragrances Lawrence Roullier White puts it, “opened the eyes - that’s the wrong organ, but you know what I mean - to other strong notes. That just wouldn’t have happened as little as five years ago. It does make you wonder what might be next - the other ‘undiscovered’ ingredients out there”.

Some argue that Africa’s rich heritage of ‘untapped’ oils and spices may be one source of inspiration. That sounds all very luxurious. But, in the meantime, there’s also an appreciation for the purely synthetic - once a dirty word in fragrance design, now an accepted tool in the making of scents that would otherwise be impossible, and which, in a sense, as oud does, aim to divide opinion. Frederic Malle and Maison Martin Margiela, for example, have both launched a fragrance inspired by the smell of lipstick (ok, so not one for the gents, though another key trend here is the breakdown in entirely manufactured distinction between ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ fragrances). Blackbird, one of those boutique makers, has played with notes of motor oil and Play-Doh. Pencil shavings, photocopy toner, over-ripe/verging on rotten fruit have been the basis of other scents. This is fragrance as art.

That it’s hard to unpick the constituent parts of these fragrances - they play on the limbic system in ways more complex than, say, an obviously orangey or cedarwood-y fragrance - has also led to a shift in naming too, away from the descriptive, polite and exotic to the downright eccentric: one of Etat Libre D’Orange’s latest is called Fat Electrician and one of Blackbird’s called Pipe Bomb, while L’Artisan Parfumer has one with the straightforward nonsense name of Dzing!.

With both the expression of individuality and choice distinction trends that don’t look to go away anytime soon, ever more unconventional experiments in fragrance design might be expected - and might be expected to sell too, even if, superficially at least, the idea can sound forced, and the results sound hard to wear. Headspace technology makes the capturing and recreation of almost any smell feasible, and the noses - often tired of being hidden behind big brand names - are itching to stretch their creativity in pulling those smells together coherently.

Women tend to be more exploratory in their choice of scents, but this may even change the way men wear fragrances - notably by leading a shift away from safe, well-worn ‘classics’ that make them smell like every other man in the office. What might be more challenging, more intriguing, would be a fragrance that made them smell like every other man in the gym - when they’re in the office. And yes, that’s been done - sweat has already inspired one niche scent as well.