In The White Chair: David Hockney

For a man who has been exhibiting his work since 1963, David Hockney still has the ability to bring 82 people together and portray them in a way that simultaneously unites and divides.

Despite the onslaught of teenage mortification it caused, my mother has three ‘artworks’ of mine hanging on the kitchen wall of our family home. Two are uninspiring carbon copies of Matisse still lifes in oil pastel, and one is a wonky Modigliani-esque acrylic ‘portrait’, abundant in colour and amateurish brush strokes. Admittedly, the embarrassment later turned to gratitude when I realised I would achieve little else worth displaying, but still it remains both a true example of motherly love equating complete delusion, and the closest I will ever get to David Hockney’s 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life (perhaps 1 Portrait and 2 Still-lifes, at a push.) Having said that, this limited early experience of some of the world’s most brilliant artists invaluably kickstarted an unending curiosity in art, and – like David Hockney – I have since regarded artists like Matisse, Modigliani and Picasso as gods of the fine art world. So I was ecstatic to learn that Hockney himself had returned to the Royal Academy with yet another exhibition, after just a four-year absence.

Now, I don’t pretend to be any sort of art expert, but a wonderful man with impeccable taste once told me “there’s no such thing as wrong or right music - only music you like”, and I like to think this is applicable to art, cinema and literature too (much to the chagrin of our Online Editor). So while I don’t have a degree in Fine Art or anything equally intellectual, I love art, I love Hockney – and I loved this exhibition.

The collection of works begins with a portrait of Hockney’s assistant, JP Gonçalves de Lima, head in hands, inconsolable after the loss of Dominic Elliot; a close friend and colleague of both artist and subject, who tragically passed away in 2013. The paint itself stands out as the most ‘worked’; the angry red zig-zag on the rug a bloody reminder of pain in its purest form, the heavy handed brushstrokes and sheer hopelessness of the subject swim in a pool of cold blue tones. It’s an incredibly sad depiction of loss – but the first of 83 paintings that would eventually make the journey from LA studio to RA showroom.

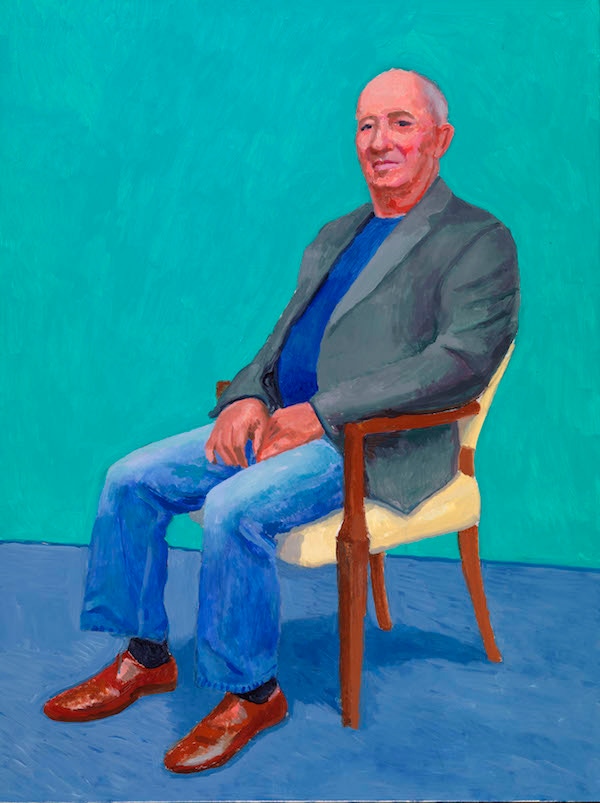

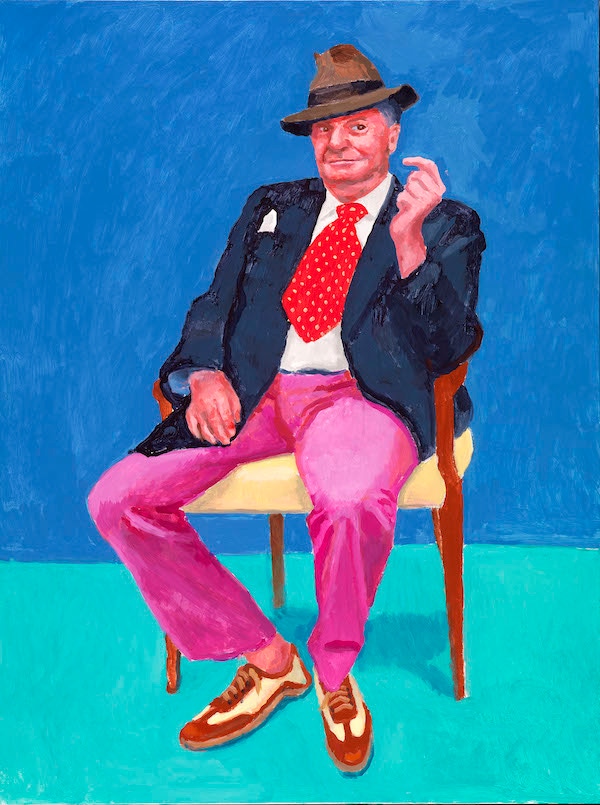

After Gonçalves de Lima’s portrait, a completely physical surrender to emotion, comes a much subtler study of body language. The early subjects (they are displayed in chronological order) show a clear sense of anticipation; excitement or interest in the process, discomfort or anxiety as a result of Hockney’s undivided attention and piercing gaze flicking only from subject to canvas and back. Joan Agajanian Quinn looks positively thrilled that she is in the presence of such genius – despite sitting for Hockney over 200 times previously. As the portraits progress, there is a sense that subjects become more comfortable – perhaps having witnessed the canvases building up in Hockney’s studio, the pressure is relieved as they realise that they are not the first. Critics have noted that although the depictions are not particularly accurate or recognisable, they maintain a sophisticated style and power in their simplicity – a stylistic trademark of Hockney’s.