REAP THE WHIRLWIND: Breguet

Two centuries after Abraham-Louis Breguet invented the tourbillon, the house that bears his name remains the mechanism’s undisputed master. A new release by Breguet and a London exhibition on the tourbillon’s evolution are testament to its enduring relevance.

The phrase ‘gravity-defying inventions’, for many, will conjure up images of the Wright brothers’ biomimetic escapades at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina; others may think of Leonardo da Vinci’s sketched-out ‘fancy-of-flight’ (to invert a popular phrase), which he called the ‘aerial screw’, and which pre-dated helicopters by half a millennium. Those whose understanding of gravity goes beyond Newton’s apple into actual equations will no doubt point to the invention of the wheel.

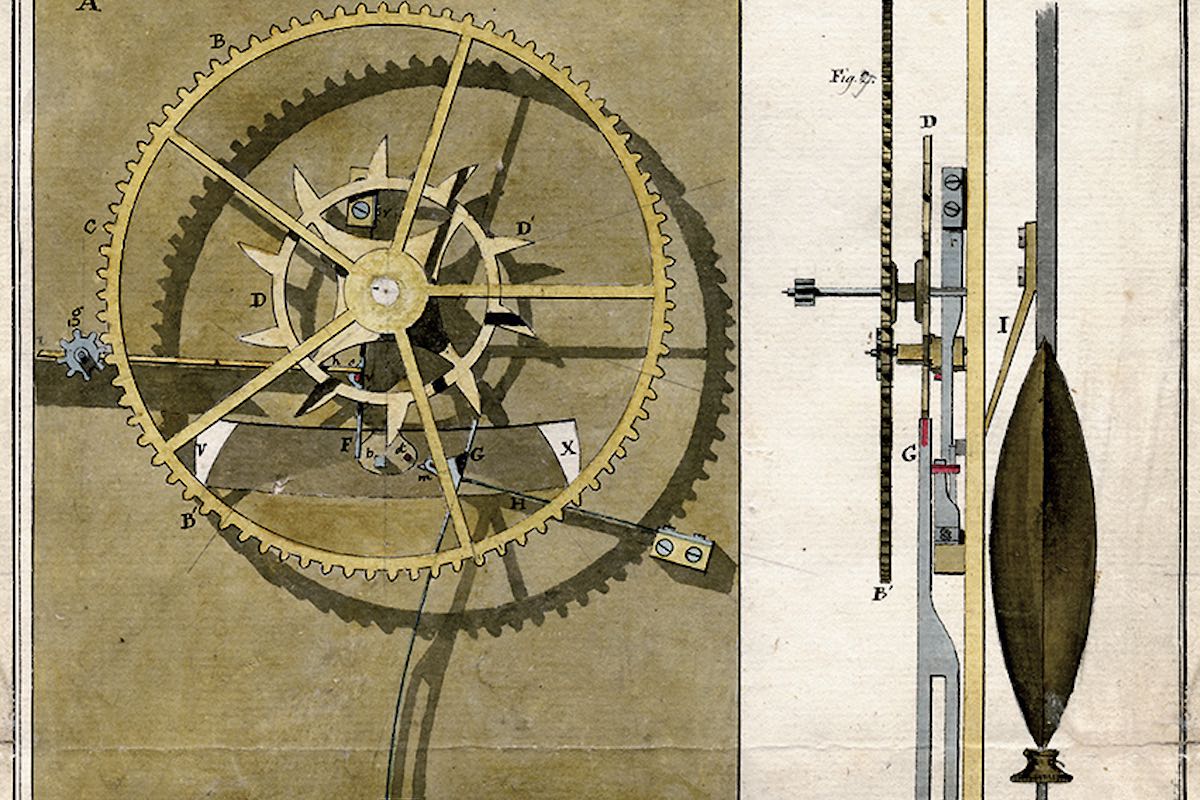

But devotees to all things horological would no doubt sooner point to a breakthrough achieved by Abraham-Louis Breguet around 1795, when watches were still exclusively worn in the pocket. Observing how gravity meddled with the performance of parts such as a watch’s pallet fork, balance wheel and hairspring — particularly when the timepiece had been laid on a flat surface — he had an epiphany that changed the course of horological history: if certain components were housed in a rotating cage, he realised, the variations in question would compensate for each other, effectively conquering one of the fundamental forces of physics.

After he patented his mechanical coup in 1801, having named it after the French word for ‘whirlwind’, he then unveiled a timepiece that would “maintain the same accuracy, whatever the vertical or inclined position of the watch” at the National Exhibition of Industrial Products in Paris five years later. The tourbillon quickly became the toast of the horological intelligentsia (Breguet’s customers by then included Marie Antoinette, the King of Spain, and Tsar Alexander I, and one particular four-minute tourbillon was sold secretly to George III, this being the height of the Napoleonic wars).

Breguet would go on to complete 35 tourbillons during his lifetime, but only 10 have survived, and the mechanism was scarce in watchmaking until recent decades, when there was a resurgence in passion for mechanical horology — a resurgence that, happily, seems to be revitalised with each passing year.

If you’re in any doubt as to how admirably Breguet’s contemporary R&D folk are honouring their founder’s famous masterstroke, a visit to the V.I.P. lounge of Watches of Switzerland in Knightsbridge is advised: there, the pieces that can be thought of as milestones leading up to the brand’s latest tourbillon offering — the Breguet Double Tourbillon 5345 Quai de l’Horloge — are being exhibited until the end of January.

The exhibition represents a Bayeux tapestry-like narrative of Breguet’s tourbillon achievements of recent years. A gripping early chapter is the Breguet Tradition 7047 with Tourbillon, Fusée and Silicon Breguet Overcoil Balance Spring, which, as the name implies, combines the tourbillon with another game-changing invention, based on movement-regulating oscillations.

From 2013 we have the Breguet Classique Tourbillon Extra-Plat Automatique 5377. A piece afforded contemporary elegance by the subtlety of the guilloché dials Breguet has become renowned for, it was, with its 7mm thick platinum case, at the time the thinnest self-winding tourbillon on the market thanks to a stroke of ingenuity of which the founding father would have approved: a peripheral rotor that winds in both directions of spin.

The following year, the world was introduced to the Breguet Classique Tourbillon Quantième Perpétuel 3797, a piece that won plaudits for the intuitive display design (the opaque sapphire hours and minutes chapter, with its metallic Roman numerals and blue steel hands, was brought to the foreground, giving appealing depth as well as legibility). Skip forwards to 2018 — but not without taking in the Marine Tourbillon Equation Marchante 5887 (with its solar time/mean time differentiating Equation of Time complication) from the previous year — and we have the arrival of the Breguet Classique Tourbillon Extra-Plat Automatique 5367. This introduced a ‘grand feu’ enamel dial to the manufacture’s Grandes Complications collection and replaced the power-reserve indicator of the watch’s predecessor with a spinel-topped, hand-bevelled tourbillon bar.

Abraham-Louis Breguet would not have imagined that his gravity-conquering innovation could be squeezed into a three-millimetre case, but that’s what was achieved the following year with the Classique Tourbillon Extra-Plat Squelette 5395, a feat achieved by, among other mini-masterstrokes, giving the silicon escapement an eye-catchingly angled shape. The piece might be called ultra-skeletonised — almost 50 per cent of the material was removed from the movement — with engraving, engine-turning and anglage (bevelling or chamfering of plate and bridge edges) making the experience of beholding it even more theatrical.

Earlier this year, a rose-gold and slate-grey dial edition of the Marine Tourbillon Équation Marchante 5887 — the 2017 release that, with its guilloché-peaked wave motif in the dial’s centre, gave a nod to Breguet’s appointment as Horloger de la Marine Royale in 1815 by the Louis XVIII — was introduced.

Meanwhile, the latest addition to Breguet’s tourbillon repertoire is the aforementioned Double Tourbillon 5345 Quai de l’Horloge. Taking its name from the gilded Conciergerie clock, installed in 1371 close to the founder’s workshop on the Île de la Cité in the middle of the Seine (Breguet was born in Switzerland, trained in Paris and Versailles, and settled in Paris in 1775), this piece is a Classique Double Tourbillon, a complication first introduced in 2006. Within that hefty yet unerringly elegant 46mm, 16.8mm-thick platinum case, a second tourbillon powered entirely by its own gear train and mainspring plays co-star in a performance that sees the entire plate rotate every 12 hours. The back plate, meanwhile, is hand-engraved with an intricate rendering of the building that housed the aforementioned workshop where the tourbillon was invented.

Breguet’s watches have captured the imaginations of intellects as diverse as Ettore Bugatti, Sir Winston Churchill and Sergei Rachmaninoff over the years, so it’s apt that the set of watches on display in Knightsbridge will delight physicists as much as F1 drivers, and engineers as much as movie stars and captains of industry.

Indeed, looking more broadly at how the mechanical watch industry keeps achieving greater levels of ingenuity, it’s as if some kind of regulating force, perhaps positioned at 3 o’clock on a disc-shaped universe, were keeping horological innovation on track and impervious to turbulent forces. A visit to the V.I.P. room at Watches of Switzerland during your next visit to London will certainly hint at such a fanciful idea.

Read the full story in Issue 73 of The Rake - on newsstands now.

Available to buy immediately now on TheRake.com as single issue, 12 month subscription or 24 month subscription.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.