REEL BRITANNIA

Tea parties in the Hills, the sound of leather on willow by Sunset Boulevard … British actors might be en vogue in the U.S. right now, but it’s nothing compared with the glory days of the twenties, when Hollywood fell hard for Blighty and an army of ex-pat thespians — with their tweeds and servants and smoking pipes — turned a corner of California into a rather overwrought version of the raj.

Hollywood loves a Brit. Leading men from the British Isles have taken over the film world: look at Oscar winner Eddie Redmayne, runner-up Benedict Cumberbatch, as well as Tom Hardy and Tom Hiddleston, who will no doubt follow them. The Americans are hiring Britons to play their presidents (Sir Daniel Day-Lewis as Abraham Lincoln), their revolutionaries (David Oyelowo as Martin Luther King, Jr), and even their superheroes: a couple of years ago, Batman (Christian Bale), Superman (Henry Cavill) and Spider-Man (Andrew Garfield) were all burgundy-passport-carrying citizens of Her Majesty. Then there are the women, led by Carey Mulligan, Keira Knightley and Emily Blunt, and we haven’t even started on television, where a running obsession with the plight of the American male hasn’t hindered the recruitment of the public-school-educated Damian Lewis and Rupert Friend to serve in their marine corps and secret service in Homeland, R.A.D.A. graduate Andrew Lincoln to fight their zombies in The Walking Dead, or Hackney lad Idris Elba to run their drug gangs in The Wire.

In fact, Hollywood loves Britain so much America is starting to worry: in an article for U.S. magazine The Atlantic, headlined ‘The Decline of the American Actor’, the critic Terrence Rafferty wrote, “This is getting embarrassing”. Well, they should spare their own blushes: Hollywood has always loved Britain. A study of the first century of the film industry shows that British actors have been there all the way, beginning with the silent pantomiming of Stan Laurel (born in Ulverston, Cumbria) and the man who turned that which is filmed into an art form called ‘film’, Charlie Chaplin of south London. And if it seems as though the British are more dominant now, it’s a drop in the ocean compared with the real British ‘invasion’ in the 1920s, when there were so many of British actors ‘over there’ that they effectively built a colony in the Hollywood Hills.

While the current generation of British leading men and women has taken over in part because they’ve finally mastered the American accent, it was for their native voices that Hollywood first fell for the British. This was the start of talking pictures, and the studio heads, most of whom were émigrés from central Europe, were convinced that the Americans who had starred in their silent films could not possibly speak on film. In panic, they turned to the British stage, and so it was that a host of British character actors, some of them second-rate and resigned to running down their careers in provincial theatres, were invited to start over in the brave new world of the movies.

It wasn’t until much later that the critic Sheridan Morley — the grandson of a leading light of this British contingent, Gladys Cooper — dubbed the resulting community the ‘Hollywood Raj’. The name was all too apt: with a few exceptions, they behaved exactly as the colonialists had in India, training teams of servants in the ways of home and firmly looking down on the natives who had been so good as to employ them. Tea was taken beside croquet lawns, tweeds and moustaches were worn in spite of the heat, and, with an arrogance conferred by history, they imposed themselves. As Morley puts it in his book The Brits in Hollywood: “Like Africa and India at the end of the nineteenth century, California at the start of the twentieth century was a place where to be English, or at the very least British, was nearly enough.”

The indulgence they were shown by their hosts allowed them to play up wickedly. From the start, this was about a very theatrical idea of Britishness. Hollywood’s idea of the country was out of date before these old boys and girls arrived, but they only made it more so. Most of the actors who arrived had served in the first world war, and were rooted in an era that had already passed, of Empire, conquest and ruling the waves. They had returned from the fields of Europe to find the theatre had been taken over by a new, more subtle, psychological form of drama for which they were ill-equipped. With some irony, the virgin territory of Hollywood and the spanking-new medium of film became a refuge where they were actively encouraged to recreate a now vanished homeland, with the added advantage of infinitely better weather.

Leading the charge was George Arliss, an old West End hand who had already worked in America for some years, on stage and in silent films. His portrayal of a great British statesman in the 1929 film Disraeli won him an Oscar (in the third year that such things existed) and launched a wave of films set in the Old Country. Encouraged by the number of British citizens they had to draw from, Hollywood produced more than 150 ‘British’ pictures between 1930 and 1945, ranging from political biopics (often starring Arliss, who would simply reproduce his Disraeli regardless of the subject) to adaptations of Dickens, stagey drawing-room melodramas, adventures of Robin Hood and tales from the Empire. This in turn attracted a further wave of thespians from Blighty, among them David Niven, who, in his memoir, The Moon's a Ballon, attributed his break to what he called “a bonanza for the British character actors”.

The anglophilia extended beyond the screen, too. Every English actor in town was at some point summoned to visit the publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst’s castle in San Simeon, California, where he played the country squire with the sheepish connivance of his actress-mistress, Marion Davies. Other producers followed suit, taking up hunting and tweed and even sending their children to boarding schools in Britain. Soon, any European actor was quietly assuming an English identity, including the Hungarian-born Leslie Howard and the Russian George Sanders — and even some Americans, notably Douglas Fairbanks Jr, who went as far as serving with the British in the second world war and received a knighthood in 1949.

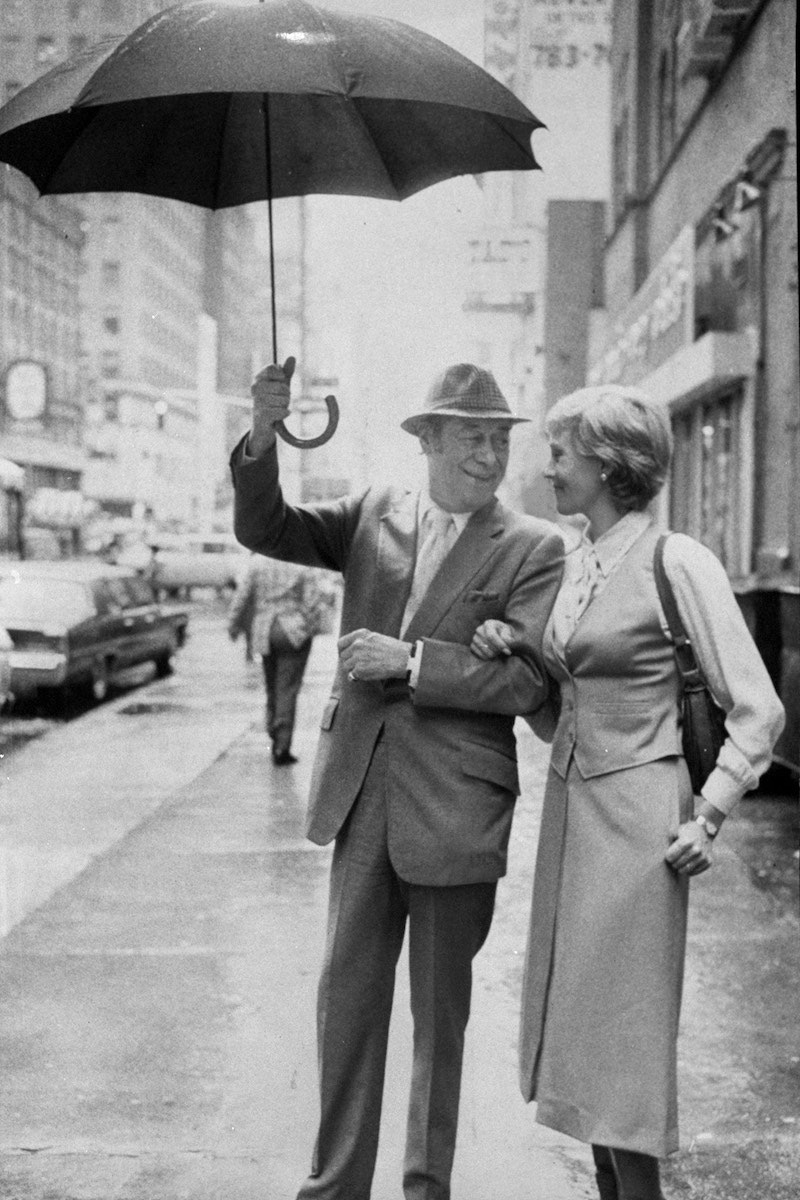

By the time Niven arrived, in 1934, the ‘Raj’ was at its height, its presiding characters in place. Chief among them, with the tacit agreement of all, was Sir Charles Aubrey Smith, then aged 71. Tall, moustachioed and pipe-smoking, with a C.V. that included Charterhouse and Cambridge and a spell fortune-hunting in South Africa, Aubrey Smith was “Great Britain personified”, The New York Times wrote in 1937. The paper continued: “Whenever he appears on the screen — his elderly figure erect, his chin up and his eyes flashing out from under those beetling brows — it is as though an invisible band were playing Rule Britannia.” When not appearing as a succession of colonels, peers, government ministers, colonial administrators and sundry other establishment figures, Aubrey Smith played host to the West End-in-exile at his villa on Coldwater Canyon Drive. Here, under a raised Union Jack, compatriots of a similar vintage — and some considerably younger — would join him for tea and polite conversation about home.

Aubrey Smith’s greatest contribution, however, was undoubtedly the Hollywood Cricket Club. While some — Ronald Colman, for example, and Basil Rathbone, known as the quintessential Sherlock Holmes — were reluctant to join the expat social circle, all reported for cricket. Smith had played for Sussex in his youth and had captained an English side in South Africa in what was later classified as a Test match; he even had a cricket-related nickname, Round the Corner, in honour of his crab-like bowling run-up, which was passed on to his house, The Round Corner, where the weathervane was made of three stumps, a bat and a ball. He founded the club — amazingly, one of 22 in the Los Angeles area at the time — in 1932, with the help of Frankenstein star Boris Karloff, whose real name was the very English William Pratt. The H.C.C. first found a home just off Sunset Boulevard, where, wrote Niven, “crashes were frequent on Sunday afternoons when amazed local drivers became distracted by the sight of white flannels and blazers on the football ground of U.C.L.A.”

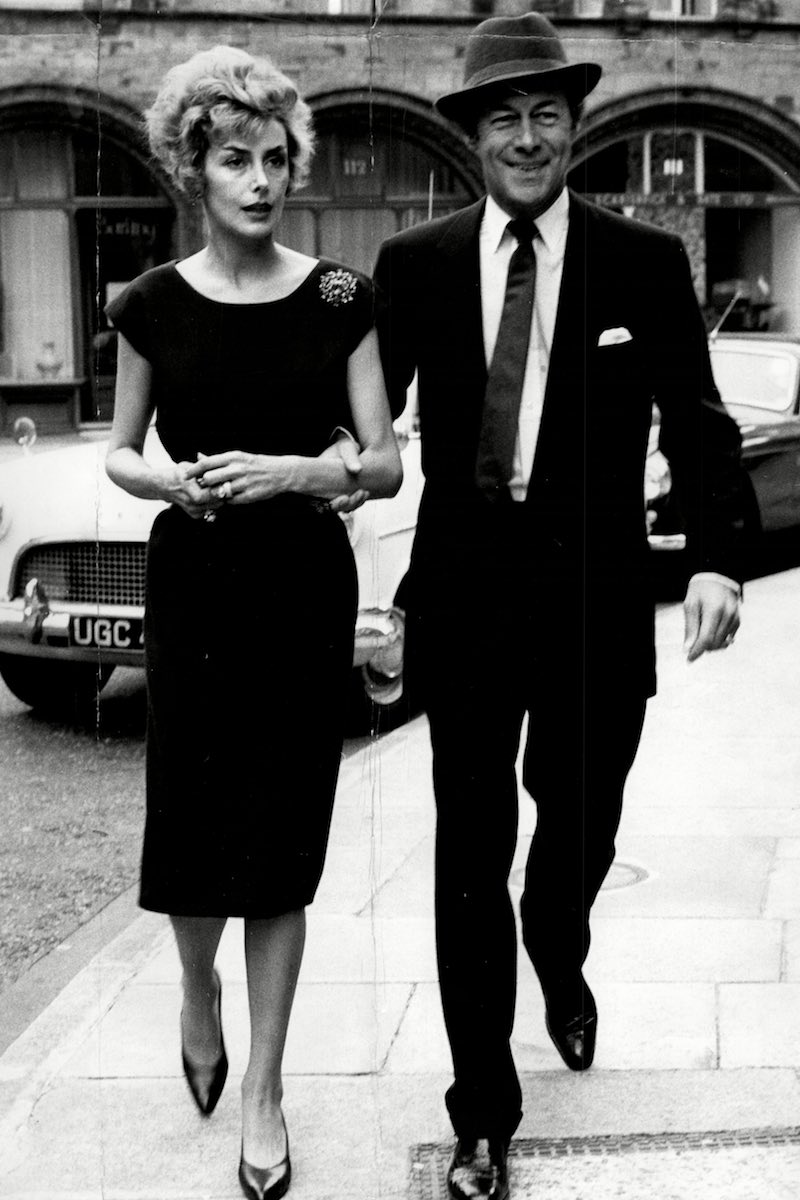

Among those who appeared in those blazers of magenta, mauve and black were Rathbone (who kept wicket), Cary Grant (a bowler), Rex Harrison and Nigel Bruce, who was Dr. Watson to Rathbone’s Sherlock. To these were added the odd token Australian (chiefly Errol Flynn) and, naturally, Fairbanks Jr. but Smith, who continued to play well into his eighties, made it clear that he considered it every Englishman’s patriotic duty to appear. Laurence Olivier, arriving in Hollywood for the first time in 1933, found a note waiting for him in his room at the Chateau Marmont that read: “There will be nets tomorrow at 9am. I trust I shall see you there.” Those who didn’t play would come to watch, including P.G. Wodehouse, who was the club’s first secretary, and leading ladies such as Elizabeth Taylor, Merle Oberon and sisters Olivia de Havilland and Joan Fontaine.

For all the tradition, this was far removed from an English village side. In the words of The Cricketer magazine, the H.C.C. was “at once rigidly British and yet gaudily American, a rich blend of country-house civility, New World chutzpah, and a discreet trysting place for the rich and famous”. Karloff drove around town in a Ford with the club’s insignia on its tyre covers — hardly the sort of thing of which his brothers, both of them high in the diplomatic service, might have approved. It was, in many ways, emblematic of the British in Hollywood, one of several equally artificial rituals that included an annual dinner for former public school boys (again, under the auspices of C. Aubrey Smith) and the New Year’s Eve gathering in a Hollywood café to hear the chimes of Big Ben on the radio. Although they carefully retained their customs and their accents, the British were altogether more influenced by the prevailing culture and a good deal more naturalised than they cared to admit.

The press loved the idea of the colony and pushed it hard, but not everyone wanted to join in. Colman, the key leading man of the 1930s, star of The Prisoner of Zenda, Beau Geste and Raffles, managed to be the archetypal Brit in Hollywood while remaining, in Niven’s words, “aloof from it all, living the life of a hermit”. He turned up for cricket and married a fellow English actor (Benita Hume), but otherwise mixed with a small group selected without bias towards home. What he did share with his compatriots, however, was a superior attitude to his host nation, a case of biting the hand that fed him (which makes the current crop of Brits and their insistence on performing in artistically cleansing arthouse movies look positively gracious). Colman was at least merely disparaging, telling a newspaper in 1926 that he loved California’s beauty, warmth and colour but that it was “almost impossible not to lose perspective out there”. Nine years later, Cedric Hardwicke went a good deal further, declaring: “I believe that God felt sorry for actors, so he gave them a place in the sun and a swimming pool; all they had to sacrifice was their talent.”

For the Hollywood Raj in general, the attitude was more straightforwardly patronising, summed up in Sheridan Morley’s story about a tea party at his grandmother’s house in the 1930s: when an unknown character appeared in their midst, one seasoned British character actor called over to his hostess, “Darling, there seems to be an American on your lawn”. The writers were much worse, led by Wodehouse, who in 1929 wrote a series of articles under the title ‘Slaves of Hollywood’, just days after he had been engaged on a salary of $2,000 a week for six months. Other literary heavyweights, such as J.B. Priestley, Anthony Powell and W.H. Auden, suffered through highly paid stints in the dream factory, though some just came to visit and sneer, including Evelyn Waugh, whose 1946 novel The Loved One included a cricket-loving old buffer called Sir Auberon Abercrombie, who was clearly based on Aubrey Smith. While this was all very well coming from the intellectual class, for the actors who indulged in such sniping there was less of an excuse. In another book about the era, Strangers in Paradise, John Russell Taylor took a more jaundiced view of the colony, asking, “Arrogance or insecurity? A little of both, perhaps”, and concluding that, “beyond their mere presence and maybe a kind of speech model they provided, [the British] had little creative contribution to make to Hollywood or the American cinema”.

Whatever their personal merits, they should have realised that they had never had it so good, never would again, quite possibly didn’t deserve it anyway — and, above all, that it wouldn’t last for ever. By the time Europe embarked on the second world war, in 1939, the British were already losing their dominance over the American psyche. Fortunately, they were distracted by the English press, who took it upon themselves to conduct a (largely misplaced) campaign to shame their actors into returning home, saying they were ‘Gone With The Wind Up’ — a particularly mean reference to Vivien Leigh’s triumph that year as the great American diva Scarlett O’Hara. In fact, most British actors of enlistment age had already attempted to sign up, and the fiercely patriotic old timers made sure the more reluctant were shamed into doing their bit.

When they returned, which almost all of them did, they found everything changed. The shattering reality of war meant that even Hollywood now saw Britain as it really was. The Victorian theme-park films it had happily churned out fell out of date and out of favour almost at once, to return, ghost-like, in popular television imports from Upstairs, Downstairs and Brideshead Revisited to Downton Abbey. Those British actors who chose to stay in Hollywood became, like Cary Grant, indistinguishable from the natives and a new generation took over, led by the still-young Elizabeth Taylor, who had grown up with Hollywood all their lives, and had barely been inside a theatre.

As the 1940s became the 1950s, mid-Atlantic accents took over from the stage-English for which the original colonists were so highly prized. Increasingly, the movies become a global industry, its stars needing to be in Rome or Berlin as often as Los Angeles. By 1960 even Niven had gone, claiming, “Hollywood had changed completely. The old camaraderie of pioneers in a one-generation business still controlled by the people who created it was gone.” Another 20 years later, it was as if the British colony had never existed. The Hollywood Cricket Club had been taken over by rock stars, and those actors who did live in the Hills — Michael Caine, for instance — did so because they liked the company better than at home. A successful actor of any nationality lived in a suitcase, or, if they were really successful, between three different homes dotted around the world.

Like them, the British stars of today, from Redmayne to Elba, are citizens of the world rather than colonists — which is another way of saying that they’re able to pass as American. Back then, there was no such pretence: America’s love for Britain was total and unconditional. Like any colony, this one was bound to reassert its independence in the end; unlike most, however, it was ruled at the request of its inhabitants, and with nothing sterner than a disapproving look. A peculiar, unreal and largely false accident of fortune it may have been, but any British heart surely feels a small glow of patriotic pride in the silly, splendid days of the Hollywood Raj.

This article originally appeared in Issue 43 of The Rake.