Reviving the Lost Art of the Bow-Tie

The classic bow-tie is the fundamental accessory for formalwear, but could it be ready for an everyday wardrobe revival? Josh Sims investigates...

Winston Churchill is rarely pictured as sentimental. But that spotted silk bow-tie that he wore - purchased from Turnbull & Asser - wasn’t simply a matter of style. If that had been the case, arguably it might well have been more co-ordinated, but the great wartime leader wore his with anything from pin-striped suit to boiler suit. Rather, that bow-tie was a reminder of his father, with whom Winston had had a difficult relationship. Lord Randolph Churchill had worn the same. But, those jowls and the cigar aside, the bow-tie became a signature for the younger statesman, so much so that the same blue and white dotted style would come to be mass-marketed as the ‘Blenheim’, after the Churchills’ family seat.

Churchill may have been the 20th century’s most famous exponent of the bow-tie, his outsized personality suiting what, today at least, can seem like one of the harder menswear accessories for mere mortals to pull off: for all that the bow-tie may have enjoyed an ironic - maybe - revival over the last decade, many have demonstrated that a fine line between between hipster and Peewee Herman. The whole point of the bow-tie is to stand out, but there’s doing that in a good way and a not so good way.

Part of the problem is that for a long time the bow-tie has seemed anachronistic, at least outside of dinner dress - for which it is (the awfulness of ‘creative black tie’ only going to prove) absolutely essential. Churchill looks the part because he was not alone among men wearing bow-ties at the time. Likewise its other exponents: Miles Davis’ early preppy style - side-vented seersucker sack coat, club-collared shirt and bow-tie - may have seen him look more jazzman meets door-to-door salesman, but wasn’t so out of keeping in the 1950s; Truman Capote may have worn a bow-tie as something of a nod towards his literary hero Mark Twain, but, again, the neckwear was still of the times.

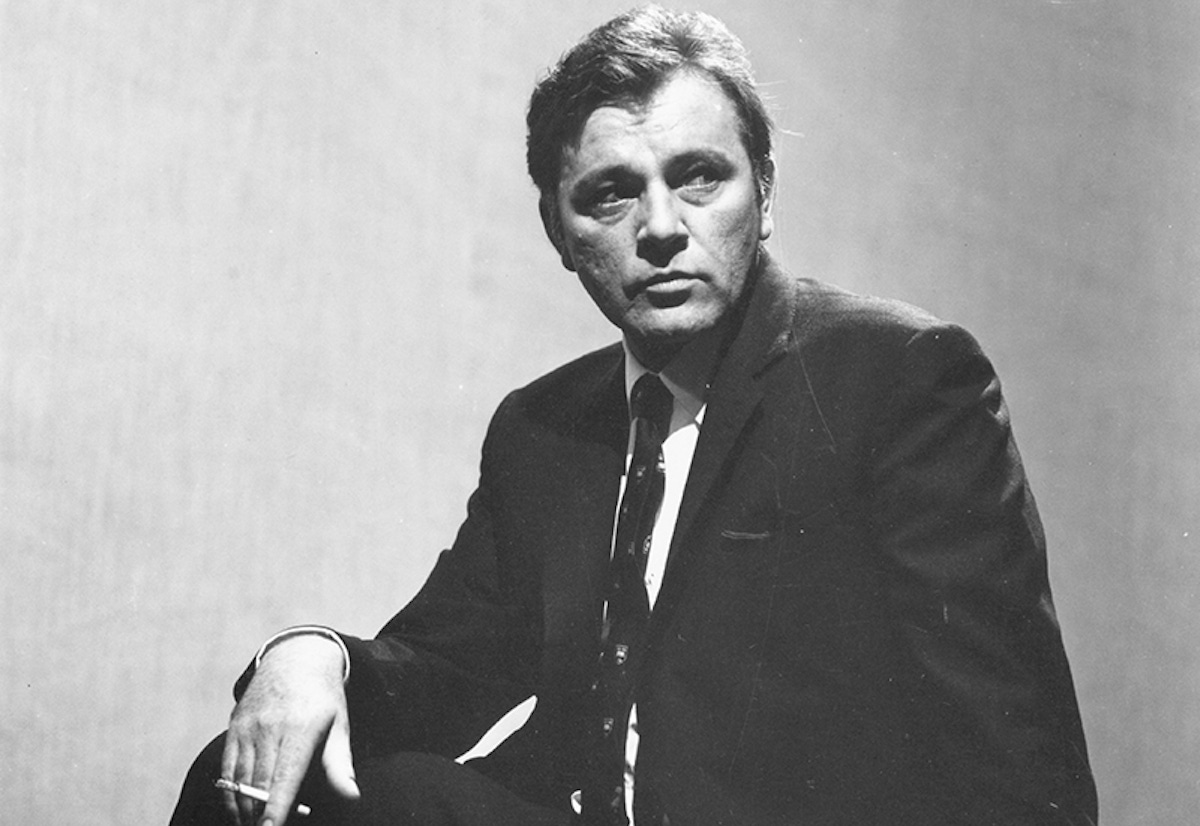

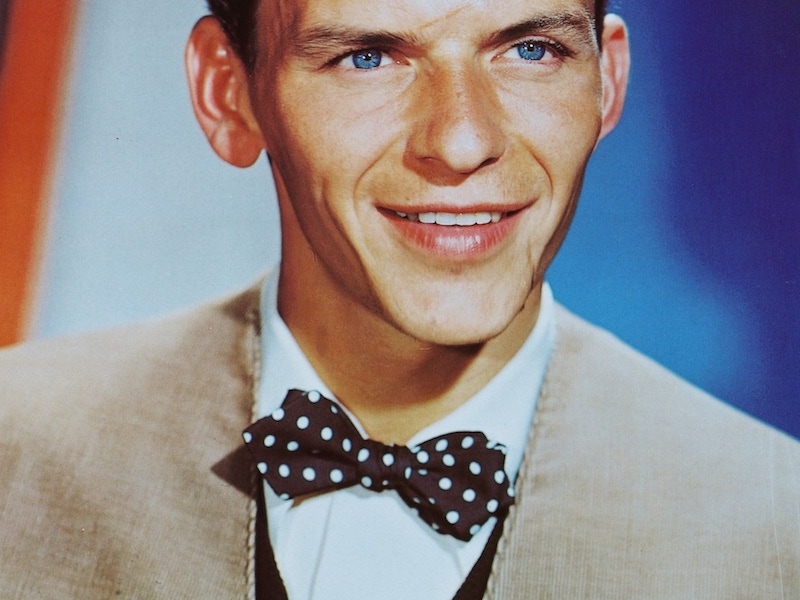

Frank Sinatra similarly looked right in a bow-tie for the early part of his career - respectable enough for all the screaming bobby soxers to take home, on an album sleeve at least, to mom and pop - before adopting the long tie, always worn loosened, collar undone, as his default look. That said, like Churchill, he looked great wearing his polka dotted bow-tie with pin-striped suit in 1955’s ‘Guys and Dolls’. But this would also mark the beginning of the end: to wear a bow-tie, rather than a sharp long tie, in the following decade was to underscore your age, more old man than Mad Man - indeed, the fact that the bow-tie persisted for eveningwear only stressed its status as a special garment worn for special occasions, further dragging it out of the wardrobe of everyday wear.

Yet the bow-tie is, in a sense, the original neckwear, pre-dating the long tie, a direct descendant of the cravat. The cravat was what upscale society made of the knotted piece of fabric worn by Croatian soldiers during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), whose necktie struck French soldiers as rather chic, taking them back home and into court fashion. This new accessory evolved over the many decades - the stock tie of the early 1700s, the Ascot of the early 1800s - becoming increasingly fanciful, until, towards the middle of the 19th century, the neat, organised bow-tie had its moment.

Then, as now, the advantages were convincing. The bow-tie framed the face and didn’t require starching. It was compact but - tied free-hand, as a bow-tie should be - also expressive, offering a decided flourish to any attire, an affect which arguably the long tie finds it harder to accomplish despite its much greater real estate. It was the proto bow-tie, not the long tie, that also first saw experimentation in the tying of knots. Come the late 19th century, advances in weaving technology allowed for the mass-manufacture of fancy fabrics for bow ties, and in turn their wearing as badges of membership for some or other club or clan. Look to the patterns possible in woven wool from a company the likes of Sera Fine Silk, or the embroidered cloths used for bow-ties from Jupe by Jackie, and it’s clear to see that textiles still make a bow-tie a great, expressive, joyful bow-tie.

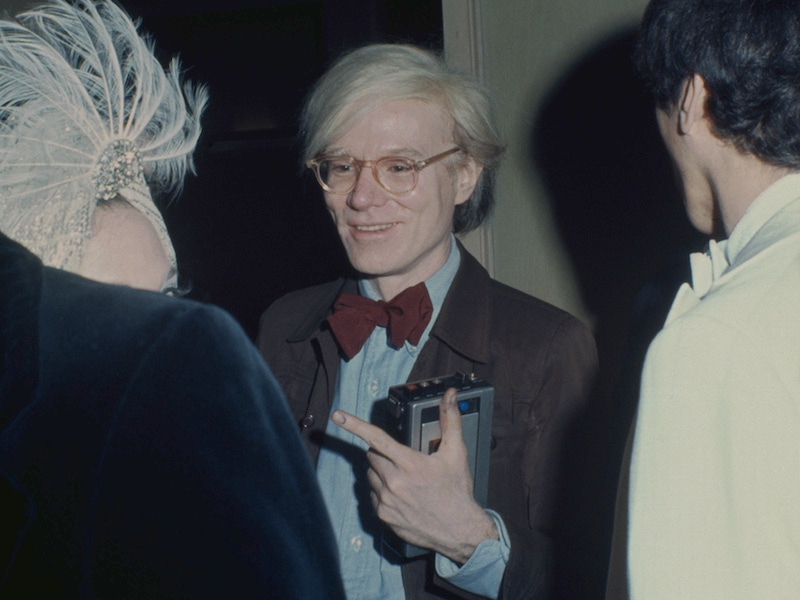

It’s hard to imagine the bow-tie re-entering the mainstream - but that’s precisely its appeal. The long tie has yet to quite dispel its association with the world of work. The long tie is, essentially, an expression of conservatism. But the bow-tie, for all its still being the unexpected choice, undercuts that: the bow-tie becomes an expression not of conformity but of individuality. This isn’t to say there’s carte blanche in wearing one - others will beg to differ, but the wearing of a bow-tie with, say, a lumberjack shirt, even with jeans or sneakers, just looks wrong. It’s bow-tie as novelty - it might as well spin in circles or squirt water too. But compare that to the way David Hockney wore a bow-tie during the 1970s and 1980s: still casually, but with a sense of mischief that went with his deliberate mis-matching of socks, patterns and anything else he could turn his artist’s eye to. Or the similar easy naturalness with which Manolo Blahnik has long worn his bow-ties - never primly, never too self-consciously, simply as a small splash of colourful fabric that signs off his look; even - although in this case it’s much more a piece of personal branding - that of science educator Bill Nye. Therein lies an example of a man who first wore a bow-tie as a bit of a joke - to play waiter at a high school banquet - but then fell in love with the accessory’s expressiveness. And the fact, as he’s noted, that it’s not so easy to get a bow-tie either in your soup or your bunsen burner. Safety first.