RUNNING WITH WOLF

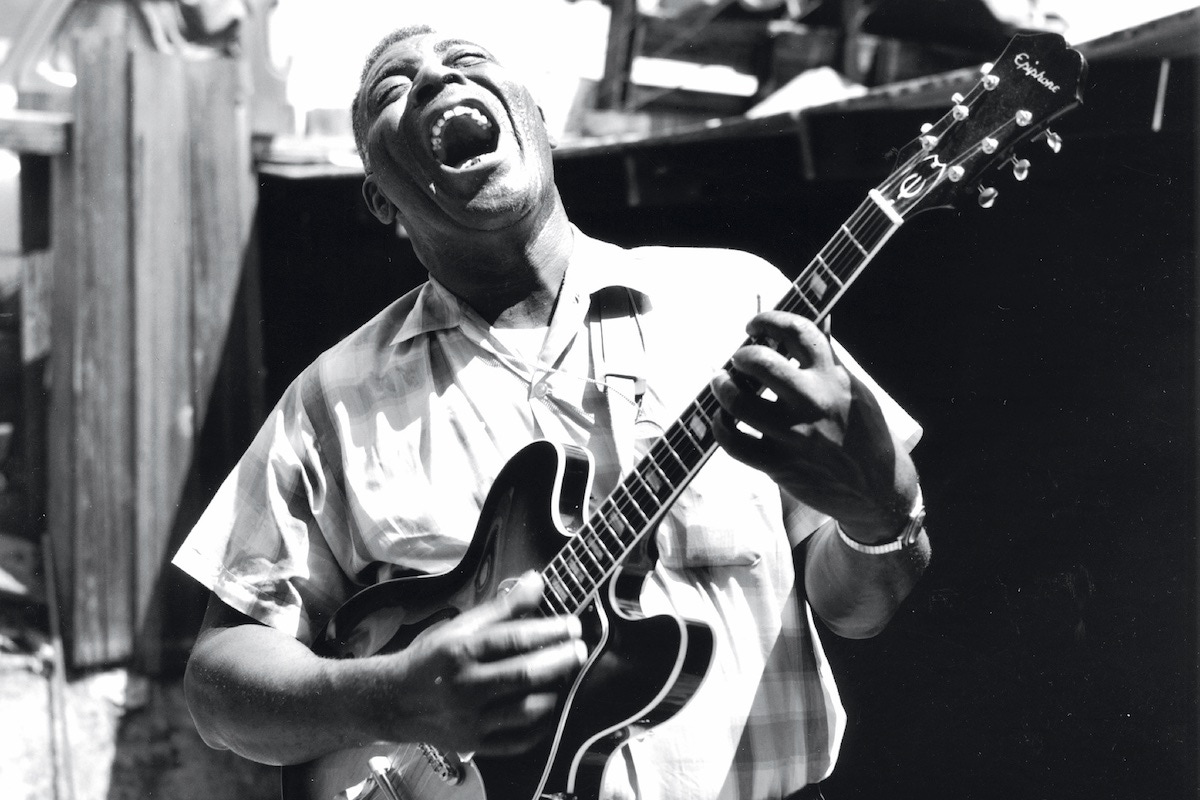

The music of the Chicago bluesman Chester Burnett retains its magnetism and vitality nearly 50 years after his death. You might know him better as Howlin’ Wolf.

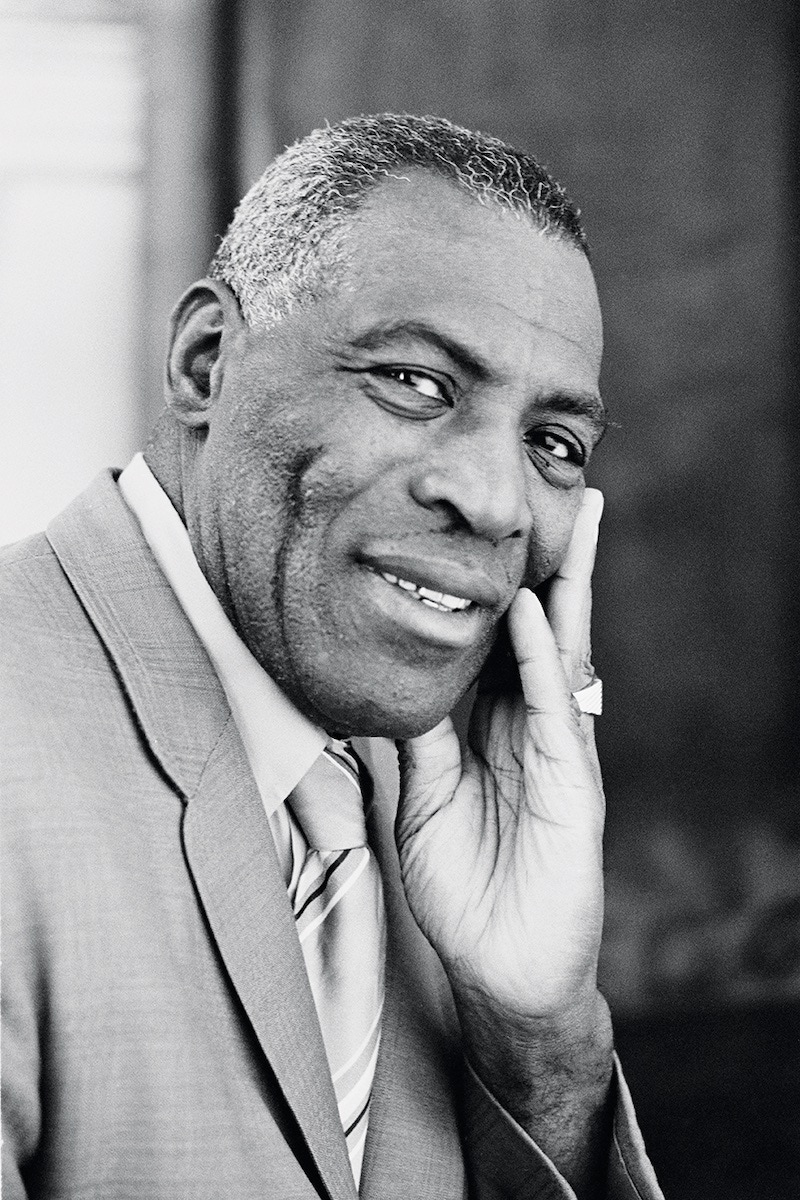

Whatever way you look at him, Howlin’ Wolf was a towering figure. At 6ft 3in and built to match, he was a seriously imposing presence, employing his physicality on stage to create a sense of authority and even threat. As a singer, his hoarse growl gave his performances an authority and drama that made them impossible to ignore. Though he dressed in sober suit and tie, his hair neatly clippered, he gave no doubt that he meant business. Even on record, the impression was the same: this was a man who could steal your woman and do you damage, and who had seen and felt things you never would.

His influence was equally heavy. British bands such as the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin formed their sound in emulation not only of his music but his charisma and mystique. Jimi Hendrix took his approach as a template, Iggy Pop harnessed his brutality, Captain Beefheart and later Tom Waits borrowed his voice, Nick Cave his darkness and mystery. And what attracted them remains as powerful as ever: listen to the astonishing, elusive Smokestack Lightnin’ and you feel the same magnetism, the timeless feeling of longing and discontent, of experience just beyond your grasp, delivered directly, as fresh and vital as anything music has thrown up in the 60 years since.

All the same, we might never have heard him. Even by the standards of the great bluesmen, recognition of his talent came late, when he was well into his forties, and partly through his own fault. For such an innovator, he was slow to seize his opportunity. Born Chester Burnett in 1910 in Mississippi, he took up the guitar at the age of 10 and picked up songs from fellow plantation workers who also happened to be the giants of Delta blues, including Charley Patton and Robert Johnson. He played in bars and on the streets but remained a farm labourer until after the war, when mechanisation meant field work was harder to find. By then he’d made a reputation for himself, and had also worked his way through a series of stage names. Bull Cow and Big Foot eventually gave way to Howlin’ Wolf, a title for which he gave several shaggy-dog explanations but which surely came from his take on the yodel of country pioneer Jimmie Rodgers.

Once he’d taken up music full-time, touring with an electric band, he was noticed by the white-led music companies that had sprung up after the war. His first sessions were at Sun in Memphis, where the resident producer, Sam Phillips, later to foster the rise of Elvis and rock ’n’ roll, recalled him as the greatest talent he encountered. From there he headed to Chicago and the Chess label, where, with Muddy Waters and others, he spearheaded what became known as Chicago blues. Loud and lively, perfect for dancing or carousing, this form was hugely popular with black audiences and then, as their attention fell away, with a new audience of white teenagers.

Read the full feature in Issue 81 of The Rake - on newsstands now.

Available to buy immediately now on TheRake.com as single issue or 12 month subscription.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.