Sex, drugs & Moroccan roll

First there was Sodom and Gomorrah, then Babylon – the great cities of vice. But human history is replete with hedonistic hangouts, and in the 1960s, writes Nick Foulkes in Issue 38 of The Rake, Morocco opened its arms to the jet set and famous.

“If you are someone escaping from the police, or merely someone escaping, then by all means come here: hemmed with hills, confronted by the sea, and looking like a white cape draped on the shores of Africa, it is an international city with an excellent climate eight months of the year.” So wrote an excitable young Truman Capote of Tangier in 1950. “Before coming here you should do three things: be inoculated for typhoid, withdraw your savings from the bank, say goodbye to your friends – heaven knows, you may never see them again. This advice is quite serious, for it is alarming, the number of travellers who have landed here on a brief holiday, then settled down and let the years go by. Because Tangier is a basin that holds you, a timeless place; the days slide by less noticed than foam in a waterfall; this, I imagine, is the way time passes in a monastery, unobtrusive and on slippered feet.”

There was a time when the seductive, addictive quality of life on the north African shores of the Mediterranean had a powerful hold upon the imagination of the more louche members of what Ian Fleming called the ‘international set’. In a time long before the Arab Spring and Aman resorts came to the Maghreb, it was the destination of choice of those among the beautiful people for whom the Riviera proved insufficiently hedonistic and exotic. Of course, in those days, north Africa was still European: Algeria was a department of France and would have to fight a bloody war against its colonial master before it could achieve independence in 1962, while both Tunisia and Morocco were French protectorates until the mid fifties.

But, at the same time, it was also Africa: moral standards, at least for European and American expats, were relaxed to the point of non-existence. Much in the way Americans used to visit Cuba to sate themselves on the island’s pleasures, northern Europeans headed to Tangier in search of a more forgiving moral and meteorological climate – the place was apparently a seething fleshpot where every depravity was catered to. The city’s wartime status as an international zone, which it would retain until 1956, added to its appeal.

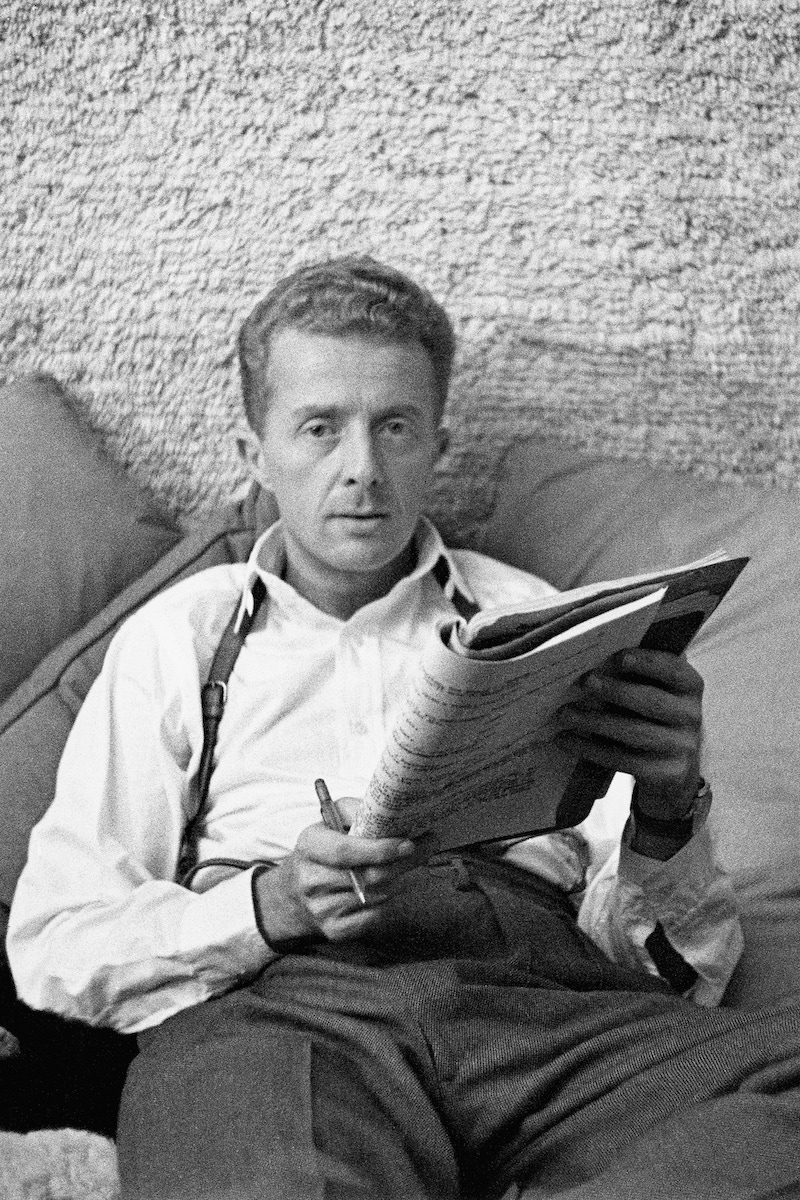

For many, it was Paul Bowles who opened their eyes to the beauty and decadence of this part of the world. He first visited at the beginning of the 1930s; he would settle there in the forties and take up residence until his death at the end of the century. It perfectly suited his métier of writing novels that – in the words of Sir Cecil Beaton – were composed of “an up-to-the-minute formula for decadence and isolation” and tended to be variations on a theme that Sir Cecil described as “the white man, faced with the impact of an exotic culture that appeals to his latently destructive sensuality, goes to seed, falls apart or dies, while cynically enjoying his detachment from his own world”.

Tangier was a place for seedy sensualists who wanted to live large on a modest budget, and it was during the thirties that the place was also discovered by the Hon. David Herbert, the elegant, indolent second son of the 15th Earl of Pembroke. Described in one of his obituaries as “immaculate in green cravat, his fingers heavy with rings”, Herbert – nicknamed ‘the Queen of Tangier’ by Ian Fleming – realised that in Tangier he could maintain an almost regal standard of living in a rambling house on the mountain overlooking the city. And for decades he held court in a warren of opulent rooms stuffed with 18th-century furniture, grand portraits, and sundry other jetsam from the world of privilege and convention on which he had turned his back, serving dinner with porcelain glasses and silver bearing the Pembroke crest.

Typical of the aristocratic expatriates that the young Capote described as having found a home in Tangier was Lady Warbanks, who would be seen around town breakfasting on fried octopus and a bottle of Pernod with her two lovers. Capote’s description of her reads like some far-fetched invention of a fevered mind. “Lady Warbanks was considered the greatest beauty in London; probably it is true, her features are finely made and she has, despite the tight sailor suits she lumps herself into, a peculiar innate style. But her morals are not all they might be, and the same may be said of her companions. About these two: one is a sassy-faced, busy youth whose tongue is like a ladle stirring in a cauldron of scandal – he knows everything; and the other friend is a tough Spanish girl with brief, slippery hair and leather-coloured eyes. She is called Sunny, and I am told that, financed by Lady Warbanks, she is on her way to becoming the only female in Morocco with an organised gang of smugglers: smuggling is a high-powered profession here, employing hundreds, and Sunny, it appears, has a boat and crew that nightly runs the straits to Spain. The precise relation of these three to each other is not altogether printable; suffice to say that between them they combine every known vice.” Woolworth heiress and prototypical poor little rich girl Barbara Hutton was another who fell under the spell of Tangier. Her house, Sidi Hosni, was a private Moorish fantasy with walls of shimmering tiles and intricately carved stucco, pierced wood screens, tinkling fountains and low divans scattered with jewel-bright cushions.

For Capote and many others, this mix of high society, low morals, hot gossip and a groaning, all-you-can-eat buffet of sexual and narcotic temptation was irresistible. But not everyone was as taken by the place. “The paint is peeling off the town and the streets are running with spit and pee and worse,” observed Ian Fleming. The creator of 007 was just as dismissive of those who lived there: “The Arabs are filthy people and hate all Europeans.” Still, at least the misanthrope was even-handed in his denigration of Tangier and its residents, confessing himself equally “fed up with buggers”, who “do absolutely nothing all day long but complain about each other and arrange flowers”.

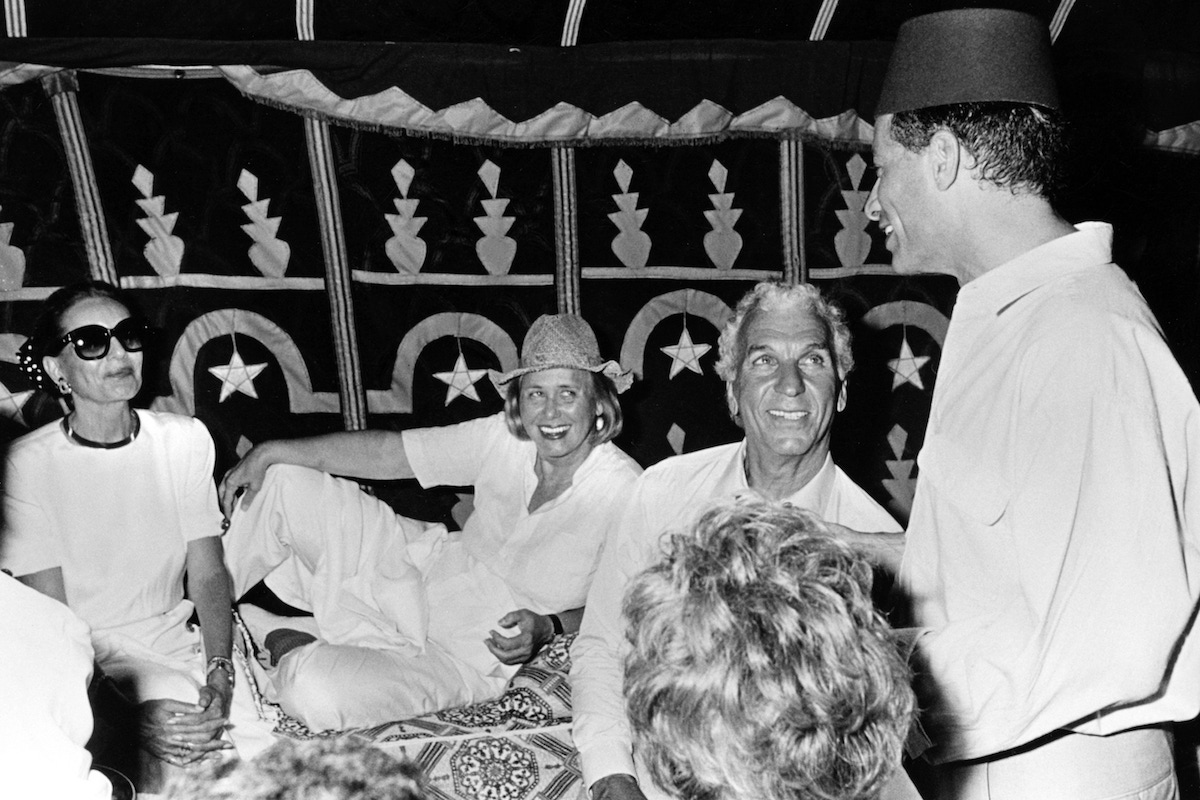

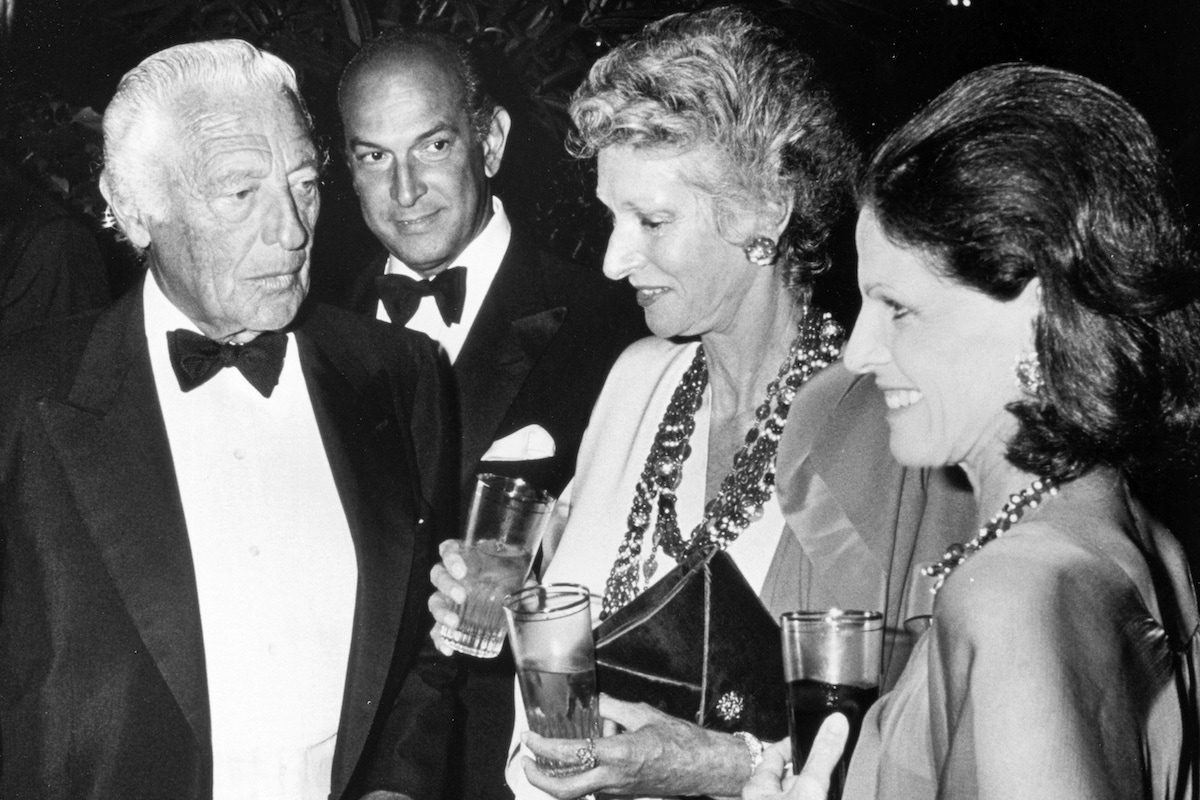

Fleming was visiting Tangier the year after the city had been reintegrated into the sovereign state of Morocco, a country that, like Fleming, took a dim view of the city’s status as a moral dustbin for dissipated Europeans and Americans. After Moroccan independence, Tangier would never be the same. It did enjoy sporadic notoriety during the sixties, when doomed British playwright and drug-fuelled sex tourist Joe Orton did his best to revive the town’s reputation as a cradle of vice and notorious British gangsters The Krays were spotted on the beach wearing suits “looking like the Blues Brothers” with knotted handkerchiefs on their heads and rolled-up trouser legs (Ronnie was cruising for underage gay sex). Then, at the end of the eighties, Malcolm Forbes held a huge party to which he invited everyone from Elizabeth Taylor to Henry Kissinger. However, the second act of the European beau monde’s love affair with Morocco would be played out almost 600km southwest of Tangier, in the ancient royal and religious city of Marrakech.

“Orangewood burning, breath of roses, mint, and spices; susurrus of leaves and fountains; music of Strauss, Wagner, The Beatles; blaze of canary-coloured walls, brass tables, flicker flame shadows; inlaid ceilings; tiles glazed acid green, eggplant and mauve; cushions embroidered a century ago by Christian slaves in Essaouira – this house in Marrakech is a house for the senses,” gushed Vogue magazine in a breathless burst of hippy hyperbole at the end of the 1960s. “Mr. and Mrs. Paul Getty, junior, would have it no other way. Between them they have kaleidoscopic talents, interests, and caches of erudition. Paul Getty, junior, who works in public relations for Getty Oil, steeps himself in music and literature. He has seen to the recordings of such rarely heard music as Mozart’s opera Il re pastore or the poetry of Christopher Logue. He cares for books and for the old, intricate crafts of their bindings. Possibly one of the least surprising things about the young Gettys is that their small son is named Tara Gabriel Galaxy Gramophone Getty (called Tara by his mother and Gramophone by his father because ‘he screeches a lot’).”

John Paul Getty, Jr. and his wife Talitha were the high priest and priestess of hippydom deluxe. Their Moroccan retreat had been built for the king’s brother in the 19th century, and with its maze-like arrangement of rooms, screens, secret doorways and tinkling fountains, it was a place in which Getty could lose himself amid the fragrant aromas of incense and hashish, and forget for a while that he was the son of the richest man in the world – Jean Paul Getty, the billionaire oil baron who was so parsimonious that he installed payphones for his guests’ use.

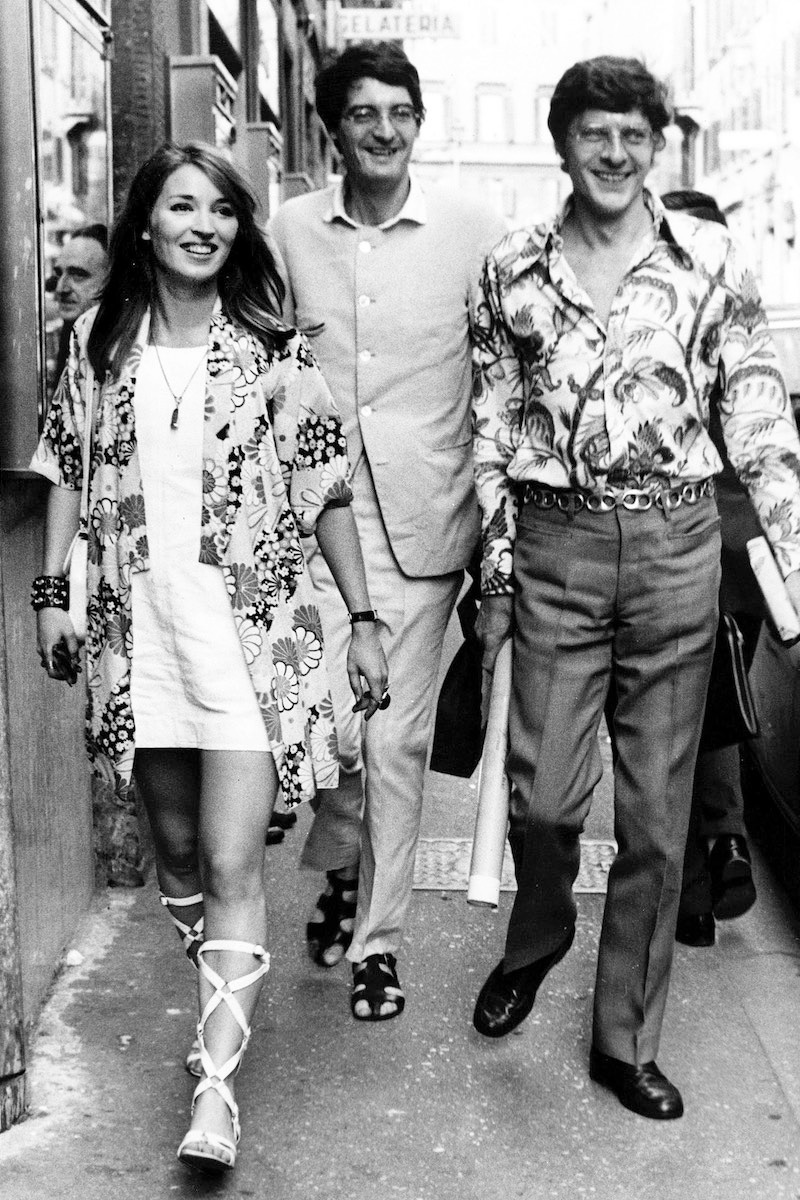

His wife had an even more tortured childhood to escape: Talitha Pol was the daughter of a Dutch painter and had been living in Bali at the time of the Japanese invasion during the second world war, and she was haunted by memories of life in the prison camp. Her mother never really recovered from the ordeal and died shortly after the war. Her father remarried Augustus John’s daughter Poppet (who had been on the Tangier scene in the thirties), and Talitha certainly made the most of this entrée into London’s artistic and social circles. By 1965 she was Tatler’s girl of the year. She crackled with an erotic charge so powerful that even Rudolf Nureyev was sexually attracted to her. She was described as “a total, complete transfixer of men”, and Getty was one of her transfixees. The couple married in Rome in December 1966, the bride wearing a white, mink-trimmed mini dress.

Each day was a trip (in more ways than one) without any fixed destination, as Vogue recounted. “She brings back entertainers – dancers, acrobats, storytellers, geomancers and magicians. A day that began with a picnic, complete with a huge onion tart, on a great flat rock near a waterfall in the Atlas Mountains may end with dinner for a houseful of young Moroccan and European friends – artists, writers, musicians, tycoons and lilies of the field – by the light of candles (‘the shadows have to be alive’) and among roses wound with mint and pyramids of tuberoses. While Salome is playing in the background, snake charmers charm and tea boys dance, balancing on their feet trays freighted with mint tea and burning candles.”

This pair of jet-set gypsies made their pilgrimage to the sacred sites along the hippy trail – Kathmandu, New Delhi, Bali, Bangkok – and returned with bric-a-brac to fill their Marrakech pleasure palace. But while they might have thought of themselves as exploring an alternative way of life, their concerns were those that had beset the idle rich for generations. “We need a thousand more cushions,” Mrs Getty told Vogue. But if getting hold of the cushions was an issue, at least she did not have to worry about having the right clothes. “You can wear anything marvellous and strange here,” Talitha said. “Everyone looks beautiful in Marrakech.”

Certainly, she did. Her looks suited the tastes of the time: long, dark straight hair; accentuated, high cheekbones; delicate arching eyebrows that seemed to have been drawn onto her flawless forehead above deep-set eyes that were made to be ringed with kohl. And in the photograph that Vogue took on the roof of their Marrakech palace, she looked comfortable enough lounging on what, it has to be said, looked like more than enough cushions. Her adoring husband, wrapped in some sort of floral dressing gown and wearing sodium-tinted glasses, looked suitably transfixed and not a little goofy in the background.

However, the defining image of the Gettys, also taken on this roof by aristocratic British photographer Lord Lichfield, featured no cushions at all. Instead, it showed a crouching Talitha, one long, beautiful white-booted leg extended, throwing open an embroidered cloak with a violet lining; one slender, ring-heavy hand gripping the elaborately crenellated parapet; her wild-eyed gaze fixing the photographer’s lens. But the biggest transformation was the husband, who had been changed, by the magic of a floor-length cowled Moroccan robe, from the awkward child of a tyrannical billionaire into a figure of sinister brooding mystery.

It was not just the defining image of the couple but one of the emblematic images of the epoch. Like Lewis Morley’s famous picture of a naked Christine Keeler astride an Arne Jacobsen-alike chair, or Peter Blake’s Sergeant Pepper album cover, it was more than just an evocative and well-composed picture, it was the distilled essence of a culture. It is an image that has gone on to inspire any number of derivative haute-bohemia magazine fashion shoots. But even if it has become a cliché beloved of a generation of fashionistas, at the time the impact of the couple – his wealth and her beauty – was explosive. The term ‘muse’ has become banal, but it is the only way to describe her relationship with Yves Saint Laurent, who had also acquired a house in Marrakech in the late sixties. “When I knew Talitha Getty,” Saint Laurent later said, “my vision completely changed.” According to Pierre Bergé, Saint Laurent’s lover and business partner, Yves and Talitha shared “the same flair – the same perception of life, more or less the same behaviour”. “It’s a decadence, a mix of Burne-Jones and Rossetti,” he said. “For these people the rest of the world is square.”

Well, not quite the rest of the world. Talitha filled the house with the elite of Swinging London: Christopher Gibbs, The Rolling Stones, Anita Pallenberg, Marianne Faithfull, Ossie Clark. And once they were there, they took drugs – lots and lots of drugs. Too stoned and too rich, the Gettys delegated the management of the household to “a marvellous secretary” who, according to a neighbour, “ran the house to perfection and with such precision, but at the same time she’d also be there cutting up hash cake for us all”. As well as cushions, the near-limitless wealth of the Gettys could buy oblivion: according to Keith Richards, Paul and Talitha Getty prided themselves on having “the best and finest opium”.

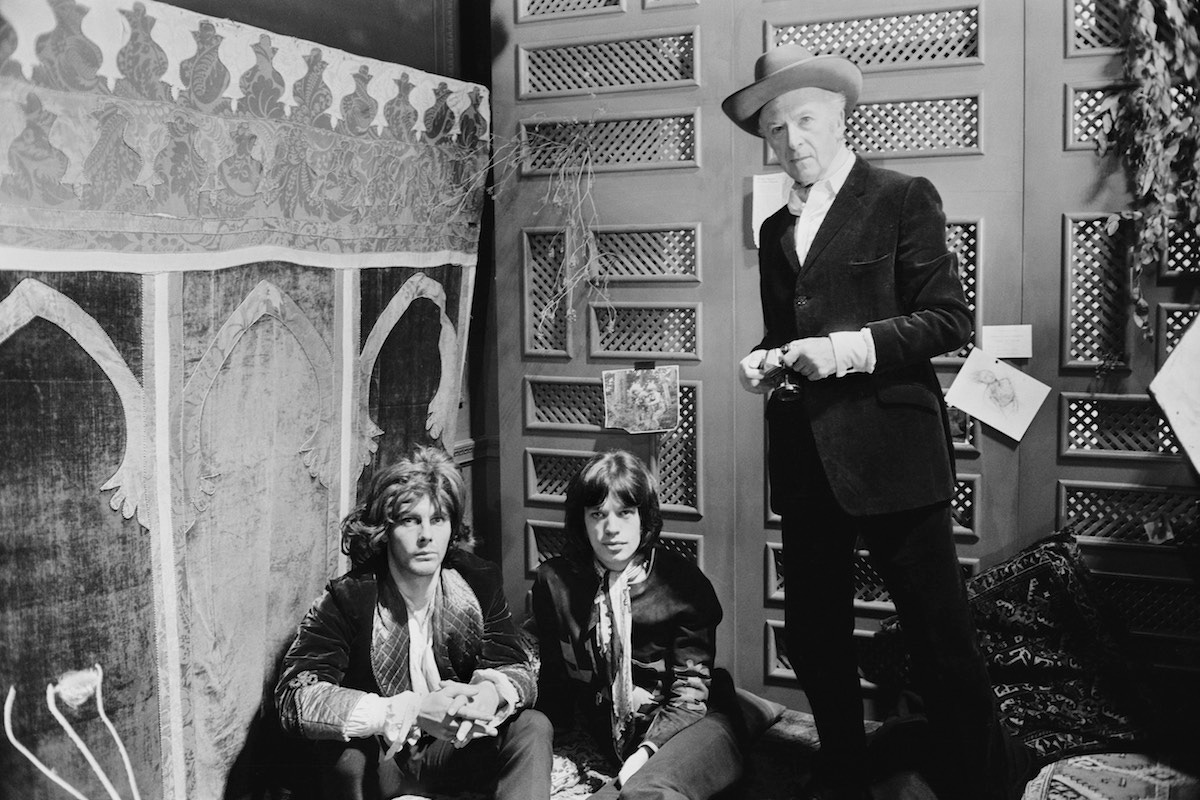

The Stones had been introduced to Morocco by Gibbs, an aristocratic Old Etonian antiques dealer as dandified as he was druggy, and who was said to have been the first man in London to wear flares. He stocked his Chelsea shop with curios and carpets sourced in Tangier, and in the summer of 1966 he took a bickering Pallenberg and Brian Jones to Morocco. This visit “affected Brian Jones more profoundly than anything since he had first heard Elmore James,” said Stones biographer Philip Norman. “It was not just the hashish, jetted up through a hookah or smouldering in the bowl of an intricately carved pipe. It was not just the clothes, caftans, djellabahs, cloaks and waistcoats, beaded with glass or silver. In Morocco, Brian found a country whose daily life, both spiritual and secular, is indivisible from music.”

And in the furore that followed the notorious Redlands drugs bust, it was to Morocco that the band headed to lie low (not that they travelled incognito: Keith Moon decided he would make the trip in his sky-blue Bentley Continental, along with Pallenberg, who had transferred her attentions to him). The car was equipped for the journey with “pop art cushions, scarlet fur rugs and sex magazines”. These priceless details are bequeathed us by Beaton, the inveterate socialite and diarist who was also in Marrakech at the time and bumped into the rock group. Beaton’s diaries record a booze-sodden madcap couple of late nights, flamboyant clothes, hash cakes and kif pipes. He finishes with the observation, “Gosh, they are a messy group. No good getting annoyed. One can only wonder as to their future. If their talent isn’t undermined by drugs, etc. They are successful rebels, all power, but no sympathy and none asked.” With the exception of poor old Brian Jones, Sir Cecil need not have worried, for almost 50 years after that action-packed Moroccan holiday, The Rolling Stones show little sign of slowing down.

By contrast, the same cannot be said of hippydom’s golden couple, the Gettys. Looking at the familiar Lichfield picture today, the young pair are preserved forever at the apogee of their psychedelic glamour. It is shocking to think that within thirty months, heroin would have claimed that beautiful woman’s life and turned her bibliophile husband into a recluse. The end of the Gettys’ marriage was as squalid as its beginnings had been glamorous. By 1971 their drug abuse had destroyed their love and he had initiated divorce proceedings. On July 10, Talitha flew to Rome to try to discuss reconciliation; they ended up arguing until three o’clock the following morning. He awoke bleary and befuddled around noon; she never opened her eyes again. Overnight, she had slipped into a coma. Heart failure ensued. By the evening, she was dead.

Getty’s hermit existence was to last a decade and a half – it is said that his recovery from addiction and seclusion was effected in great part by his love of cricket, a game to which he was introduced by none other than Sir Mick Jagger.

Originally published in Issue 38 of The Rake.

Subscribe and buy single issues here.