Sica and ye shall find

Originally featured in Issue 36 of The Rake, James Medd examines how Neapolitan style icon and Oscar-winning director Vittorio De Sica imbued his work with his inimitable spirit, giving even his self-confessed “bad films” a touch of playfulness and comic flair, as well as a sense of sophistication.

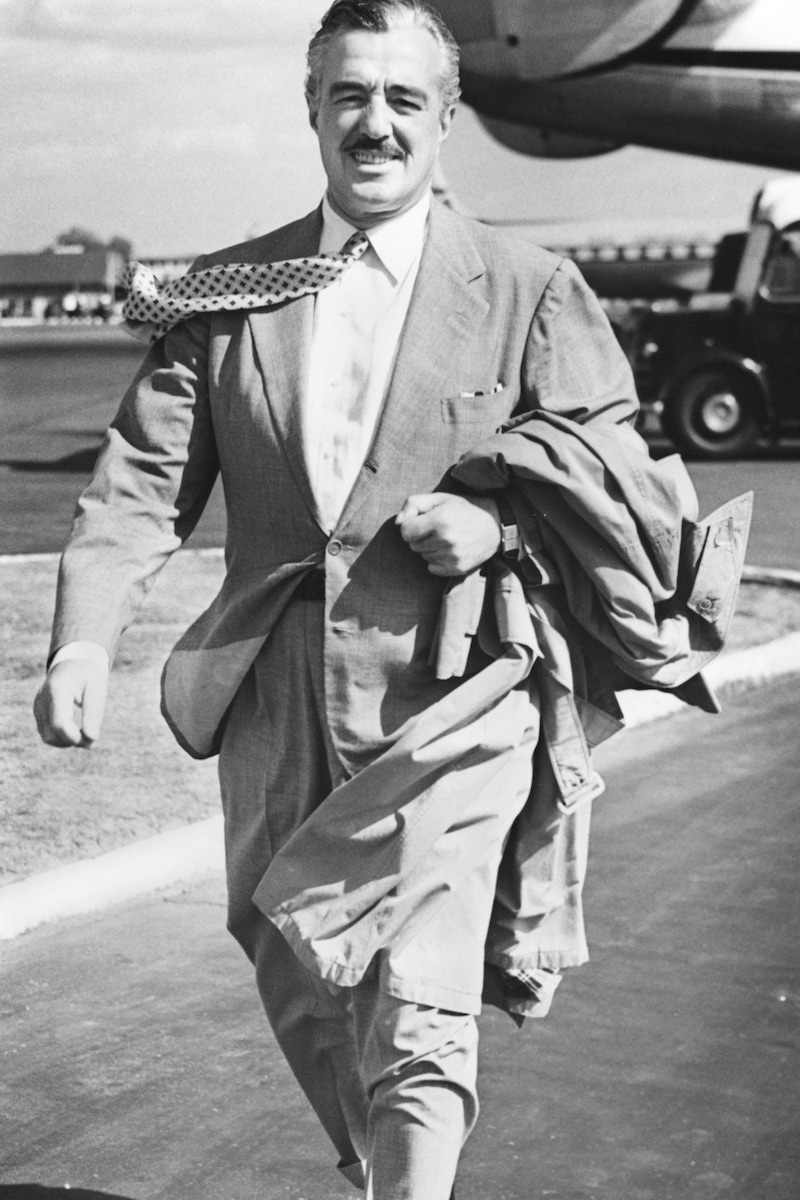

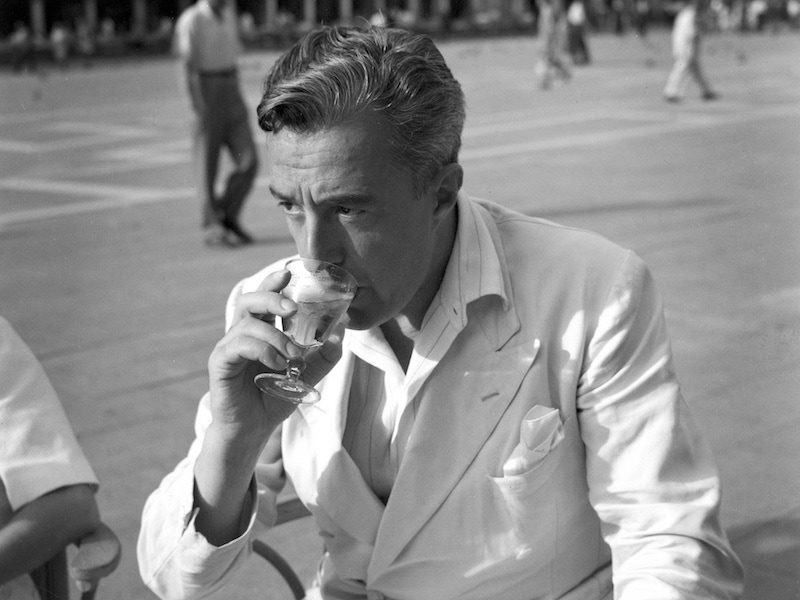

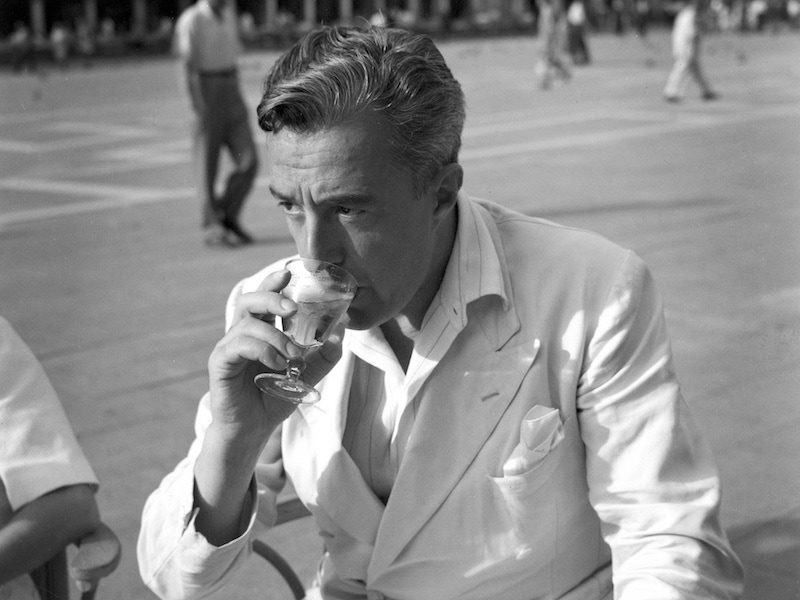

We admire the Italians for many things. For the military might of the Roman Empire, for their cuisine, for their way with coffee. Perhaps above all, though, we admire them for their art and their style. Vittorio De Sica achieved greatness in both. Over 55 years, he directed 35 films and acted in more than 150, won Oscars before foreign-language films even qualified and profoundly influenced the course of cinema as an art form. And he did this while dressed superbly, in a manner that came to epitomise modern Italian style.

De Sica first found fame as a matinee idol in the ’20s. With an elegant Roman profile, he was a romantic lead who combined an air of unruffled authority, poise and composure with wit and charm. He had been born into a poor family at the turn of the 20th century, but reinvented himself on the stage, taking up acting at an early age after his parents moved from Sora, in Lazio, to Naples. By his 20s, he was a leading man in Tatiana Pavlova’s famous theatre company and building a parallel film career that, with the success of 1932 romantic comedy Gli uomini, che mascalzoni! (What Rascals Men Are!), was to make him Italy’s answer to Cary Grant.

Both onscreen and off, he was immaculate. In suit, tie and fedora, he was always formal, but without ever looking stuffy or out of touch. In this, it helped that he lived in Naples, where a style was emerging that fitted him perfectly: a new vogue for unstructured suits, removing the stiffness and padding from English tailoring to create cuts that suited the Italian climate and temperament. (How to gesture in the appropriate Latin manner when confined by Savile Row’s strictures, after all?) With sloped shoulders, a looser fit and wider lapels, it was smart but relaxed, loose but still smooth, and more conducive to individual expression. Like King Victor Emmanuel III and the Duke of Windsor, he patronised Vincenzo Attolini of the London House, owned by Gennaro Rubinacci, Naples’s arbiter of style at the time. Although he also wore suits by Caraceni of Rome, and from all over Florence, he remains an icon of the Neapolitan style, which was soon challenging London’s domination and — taking into account the movement to a slimmer silhouette — is the dominant male fashion today.

Like his sense of style, De Sica’s genius lay in his ability to combine the formal and playful, light and shade, the happily diverting and the highly serious. By the ’40s, now working as both actor and director, he turned to weightier matters. Under the Fascist rule of Benito Mussolini, Italy became a darker place; De Sica’s sympathies were with the people of Italy and the Communist party. Having spent World War II engaged in a religious work, La porta del cielo (Doorway to Heaven), in order to avoid being conscripted, he found an outlet for this in 1946 with the extraordinary Sciuscià (Shoeshine), which told the story of two children struggling to survive in Italy under postwar American occupation. Filmed documentary-style, and improvised with non-professional actors on location, this was to be one of the foundations of what became known as neorealism.

In this, he was joined by two other great Italian directors of the time, Roberto Rossellini and Luchino Visconti, although as he said, “It isn’t as though we were all sitting around some cafe table on the Via Veneto one day and suddenly we decided, ‘Let’s go invent neorealism.’” Instead, all three were combining necessity and invention, working with the limited facilities left after the bombing of Cinecittà, Rome’s vast studio complex, but also reacting to the influence of Hollywood and of ever-weaker Italian copies, and to the overwhelming effects of war, which had left the country in poverty and despair.

Faith in man’s essential goodness was at the heart of De Sica’s films of the period, and never more so than in the immortal Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) of 1948, the heartrending story of a father’s desperate hunt for the bicycle that would mean the difference between survival and disaster for him and his family. Shot in naturalistic style against the backdrop of a city in deep crisis, it has retained its power over almost seven decades. Profoundly moving and humane but without an ounce of sentimentality, it has been an acknowledged influence on art-house cinema from the French Nouvelle Vague to Ken Loach.

Both Sciuscià and Ladri di biciclette were awarded honorary Oscars, but on the whole, neorealism made for great art and bad business. After the total commercial failure of 1952’s Umberto D., the story of a pensioner, his dog and a young maid, De Sica acknowledged that Italy wanted escapist fare rather than reflection, and he was more than able to furnish them with this. For his next movie, 1953’s Stazione Termini (aka Indiscretion of an American Wife), he went to Hollywood for a script co-written by Truman Capote and starring the incomparable Montgomery Clift. It was to be a baptism into the American way, with producer David O. Selznick insisting that the female lead be played by his wife Jennifer Jones, a diva of the worst sort. At one point, Jones tried to save herself from having to wear a particular hat by flushing it down a lavatory; De Sica, still fresh from the neorealist years of making-do and mending, noted that this hated prop, made by Christian Dior, was worth the entire budget of Bicycle Thieves.

It was not as if De Sica didn’t know what he was getting into: the same Selznick had offered to fund that very film if Cary Grant was cast as its star. De Sica had his reasons for turning his back on political art, not the least of them a terrific appetite for gambling that meant money was always needed. This was no secret; indeed gambling was a frequent motif in his films, as in 1954’s The Gold of Naples, in which he played a count who loses a card game to a young boy. He also, in rather complicated fashion, had two families to support. There was his first wife, Giuditta Rissone, and their daughter Emi, and then there was his second, Spanish actress Maria Mercader, and their two sons, Manuel and Christian. Although he divorced Rissone in 1954, he continued to celebrate Christmas and New Year with her in order to keep faith with his daughter — even going so far as to turn back the clock in his home in order to manage both.

It worked because he could carry it off, just as he carried off the differing styles and quality of his films. It was frequently said that he was underusing or had sold out his talent by making the romantic comedies in which he specialised from the ’50s. His reply, given in 1971, was that “All my good films, which I financed myself, made nothing. Only my bad films made money”. What could he do but shrug and, very elegantly, carry on? After all, these films still made use of his talents. His own acting experience ensured that he was unusually skilled at working with actors, but his sense of style and openness, his easy expression, all gave his work a touch of playfulness and comic flair, as well as a sense of sophistication.

In 1971, two years before his death, he won another Oscar for Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini (The Garden of the Finzi-Continis), an adaptation of the novel about the murder of Jews in Ferrara during the Holocaust. If its award was partly sentimental, it still suggested that quality had not fallen off entirely. And beside this, these later, lighter films introduced the world to the wonders of Sophia Loren, the greatest of Italy’s cinematic divas. She starred in 1954’s The Gold of Naples, and won an Oscar with his 1960 film La ciociara (Two Women). He paired her with the great Marcello Mastroianni in 1963’s Ieri, oggi, domani (Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow) and the following year’s Filumena Marturano (Marriage, Italian Style); she even starred in his final film, Il viaggio (The Voyage). He also made a star of Gina Lollobrigida (in Anna di Brooklyn, 1958), the only woman to challenge Loren’s crown, and worked with some of Hollywood’s leading ladies: Shirley MacLaine in Woman Times Seven (1967), and Faye Dunaway in 1968’s Amanti (A Place for Lovers).

And if this was not his greatest period for direction, then he made up for it in person, with acting performances that proved his substance. The first couple among many were Major Rinaldi in 1957’s A Farewell to Arms, which earned him an Oscar nomination, and the wartime gambler and collaborator who proves himself in Rossellini’s General Della Rovere (1959). Whatever the role, De Sica brought grace and grandeur, his youthful charm transformed into an air of nobility. His was a style that only grew richer with time, and which always enhanced his surroundings.

This article originally appeared in Issue 36 of The Rake.