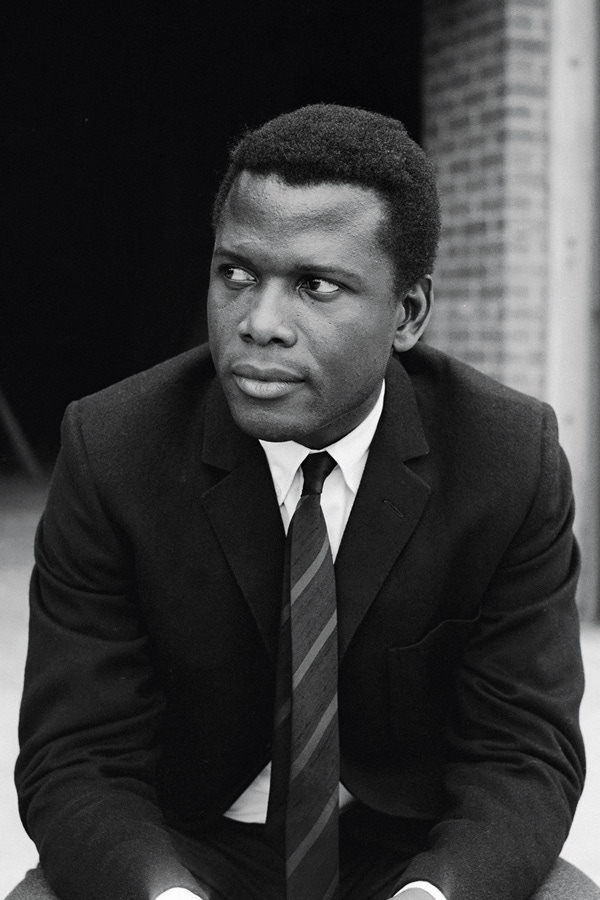

Sidney Poitier: The Defiant One

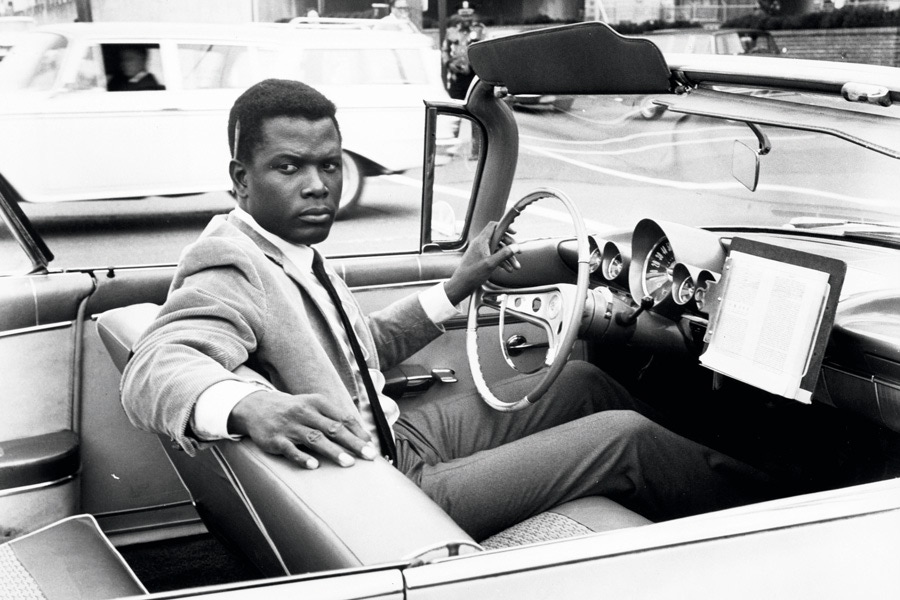

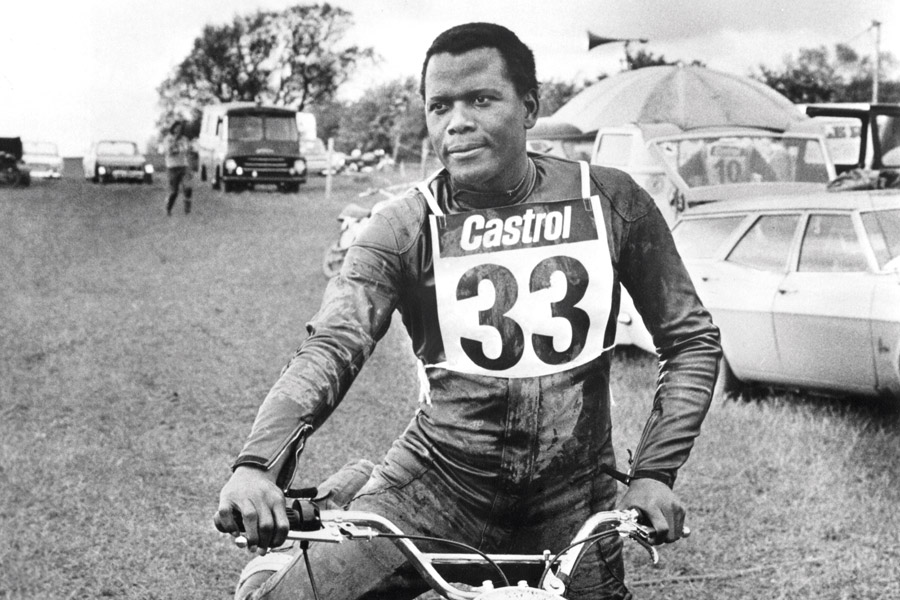

His films may feel a bit old fashioned now, but in this age of male introspection, Sidney Poitier’s uncomplicated heroism is a welcome reassurance.

The most important American film of 2017, and the worthiest successor to Moonlight’s best picture Oscar, was Get Out, a psychological horror-satire about a white woman who brings her black boyfriend home to meet her parents. It is a masterpiece: immaculately paced, queasily perceptive to the hypocrisies of white elites, a rise-through-the-octaves howl against semi-camouflaged prejudice.

The plot could also be read as a Trump-era riff on Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner, a landmark film released half a century before it with a similarly symbolic representation of the generation above. If Get Out cleverly cast actors with progressive associations (indie darling Catherine Keener and The West Wing’s Bradley Whitford), Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner chose holy cows Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy as emblems of a Hollywood establishment charmed by the courtesy, intelligence and restraint of the leading black actor of the time. That actor, of course, was Sidney Poitier.

Joseph L. Mankiewicz gave Poitier his first notable screen role, as a tolerant doctor who tends to a racist thug in No Way Out (1950), a film that climaxes with the line, “Don’t cry, white boy. You’re gonna live.” In Blackboard Jungle (1955), the best of Poitier’s early films, he played a rebellious pupil who defends the liberal teacher in a knife-fight against a violent pupil, an unusually gritty scene and an omen of his own teacher role to come.

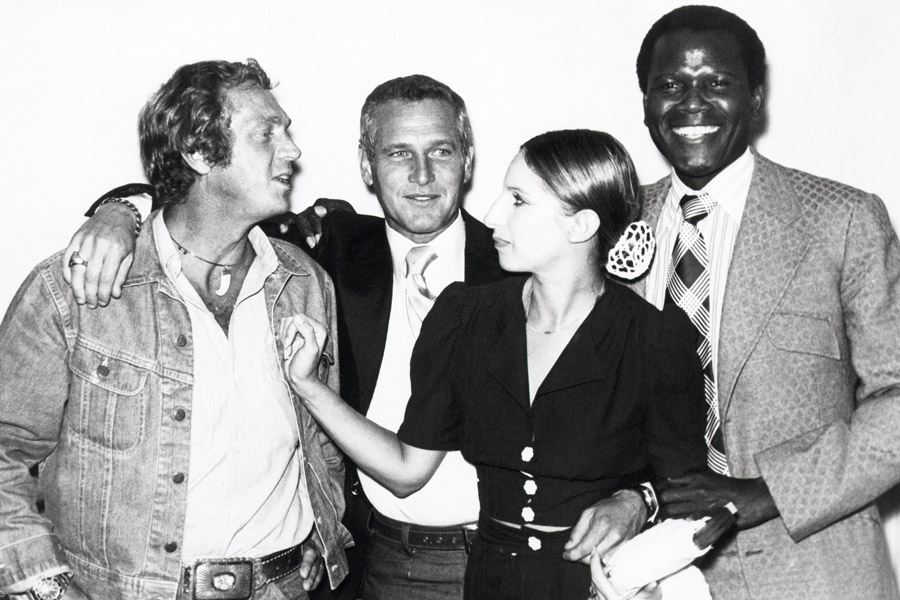

A figure of charismatic reassurance, Poitier pioneered the on-screen interracial friendship. In Edge of the City (1957), he befriends John Cassavetes’s drifter. He saves the life of Tony Curtis, the racist prisoner to whom he is chained, in Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones, a role for which he won a BAFTA and a Berlin Silver Bear. In his most stylish film, the nouvelle vague-infused, Duke Ellington-scored Paris Blues (1961), Poitier double-dates with Paul Newman and plays jazz with Louis Armstrong.

Poitier lamented that, when he started out, the roles for black actors were “always negative, buffoons, clowns, shuffling butlers, really misfits. This was the background when I came along 20 years ago and I chose not to be a party to the stereotyping… I have four children… They go to the movies all the time, but they rarely see themselves reflected there.”

His handyman-hero Homer builds a chapel for five nuns in Lilies of the Field (1963), a film that seems a little twee now, but for which Poitier became the first black winner of the Oscar for best actor, beating Rex Harrison, Richard Harris, Albert Finney and Paul Newman. Collecting his award from a delighted Anne Bancroft, he graciously stated his debt to “countless numbers of people”. Cut from a similar well-meaning, if over-literal, cloth was A Patch of Blue (1965), in which a blind woman falls in love with Poitier, unaware he’s black, despite the outrage of her mother.

Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner was a tasteful play for today, in which Spencer Tracy’s starchy patriarch softens and gives a famous monologue about love, which made his real-life wife, Hepburn, cry because she knew he was dying at the time. Criticised since for its neatness and idealism, it is a film more important for its existence in the mainstream than as a complicated work of avant-garde artistry.

In the Heat of the Night gives Poitier an even tougher time. Scored by Quincy Jones and edited by Harold and Maude director Hal Ashby, its steamy, seamy palate links the social realism of the fifties to the seventies kineticism of Sidney Lumet. Poitier plays Virgil Tibbs, a detective partnered with Rod Steiger’s bigoted police chief. Two iconic moments still reverberate. When Steiger slaps Poitier, Poitier slaps back (a vicarious riposte to the boy on the bicycle from Poitier’s youth). Then, after Steiger asks him what they call him where he’s from, Poitier baritones: “They call me Mister Tibbs!”

At the time and since, the latter two films have been dismissed in certain quarters for their sense of white liberal self-congratulation. But they were still first-time breakthroughs, unprecedented depictions of certain acts and attitudes in mainstream film, in a year when the U.S. Supreme Court had only just ruled that anti-miscegenation laws were unconstitutional.

Teacher, doctor, policeman, Poitier himself was accused of being an Uncle Tom. The contemporary black film critic Donald Bogle said that his characters “spoke proper English, dressed conservatively” and were “non-funky, almost sexless and sterile… The perfect dream for white liberals anxious to have a coloured man in for lunch or dinner.” Admittedly, the films had none of the verve or swagger of, say, Richard Roundtree’s Shaft (1971). But as Poitier said: “I’m the only Negro actor who works with any degree of regularity. Wait till there are six of us, then one of us can play villains all the time.”

Read the full story in Issue 56 of The Rake. Subscribe here.

Sidney Poitier after winning an Academy Award for his role in Lilies of the Field.

Sidney Poitier after winning an Academy Award for his role in Lilies of the Field.