Restored and Remastered: Bringing Classic Cars Back to Life

Classic cars are increasingly being upgraded and improved to fulfil the demands of the modern driving experience whilst maintaining a certain timeless aesthetic.

David Brown’s introduction to classic cars less than impressed him. “I was really looking forward to driving this Ferrari Daytona - and it was like driving a truck,” he says. And he should know - he speaks as a man whose career has been in making lumbering earth-moving equipment. “Then it broke down,” he adds, sounding very disappointed. “Of course the car looked fantastic, but the technology was very dated. The fact is that many classic cars of the past are wonderful in terms of styling, but by today’s standards they’re mechanically awful.”

That gave him an idea: why not take a classic car and - perhaps to the chagrin of the purists - completely overhaul it, both inside and under the bonnet, with modern components? The result would be a more assured, more comfortable, more reliable and safer vehicle, but with all of the style that modern car design so often fails to offer. The result was the foundation of David Brown Automotive and an offering that now includes a Mini that would have made the ‘The Italian Job’ a done deal - it’s ‘Remastered’, as the company puts it - and the Speedback, which nods to Aston Martin’s DB series.

The restoration of vintage cars has been a thriving business for 50 years or so. But now there’s a growing market for this whole new level of upgrading. As Brown puts it, this is a less a restoration as a “re-imagining. It’s taking the original car and making it better”. That’s not to say each car is just a retro shell around modern engineering. Many original parts are retained, the likes of the gearbox and suspension, for example. But even these get worked up - stripped, re-built, glass-blasted and powder-coated. Where the original tech is salvageable but doesn’t offer the performance standard demanded by many drivers today, it’s replaced with a modern equivalent.

It’s an idea that is spreading too. Eagle, for example, is a British company that, since 2014, has done the same with the Jaguar E-Type. The UK’s foremost dealer in the sports-car that defined the 60s, the company was founded by Hugh Pearman. Like Brown’s experience, Pearman’s lightbulb moment came after a customer who’d bought an E-Type from him “complained why so often vintage cars like these are, as he put it, ‘more bank notes for the shredder’, and asked why it wasn’t possible to restore an E-Type to such a degree that it was effectively a modern car” - which is precisely what Eagle went on to do.

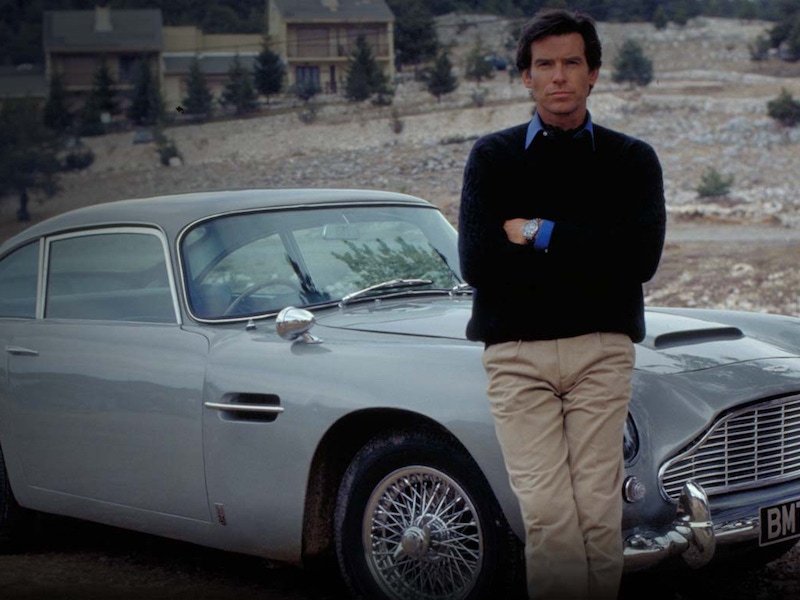

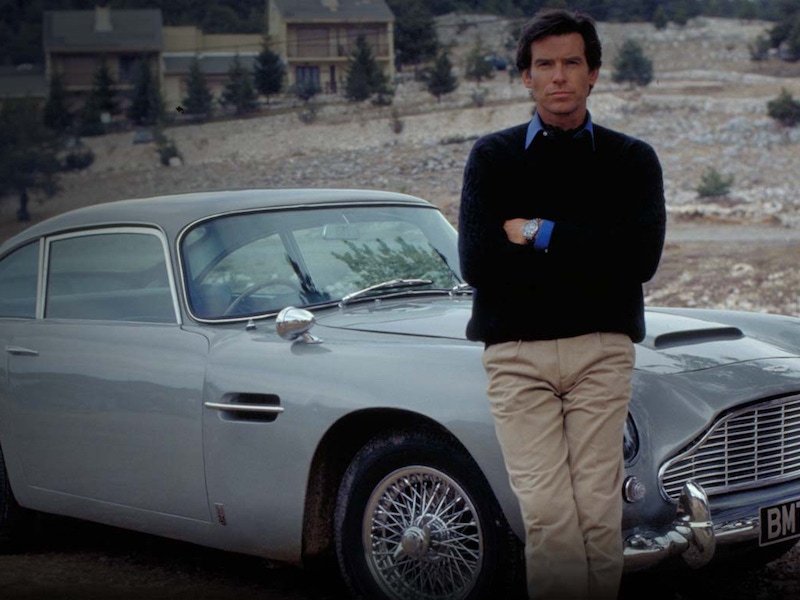

Naturally enough Jaguar itself has since launched its Reborn programme, by which the maker will offer arguably its most iconic design fully restored to the original factory specifications, improving safety aspects where necessary and, if customers request, upgrading the likes of cooling, gearbox and brakes - which is to say all of the problems with the original car. Land Rover now offers the same service for its first-generation Range Rovers. Aston Martin can re-build you a DB5 to the ‘Goldfinger’ spec, right down to all the Bondian gadgets.

If you want a Jensen Interceptor - surely one of the most striking, but also one of the most mechanically troubled of British car designs of the 1960s and 1970s - you can turn to David Duerden at JIA, which has been producing its ‘R’ version of the model for almost a decade. More recently, in recognition of the growing demand for SUVs - expect classic SUVs to the be next boom market - it’s launched the Range Rover Chieftain.

“Some of the greatest classics fail to fulfill their promise in the context of modern life,” as JIA delicately puts it; it builds cars that are “sensitive to heritage [but] tailored for the driver experience”. All of which is another way of saying it takes the rubbishness out of old cars and leaves the core design that remains alluring to petrol-heads and aesthetes alike.

“Basically we dial out the weaknesses of the 1960s models while retaining the spirit of the original cars,” as Eagle’s Pearman puts it. And that, he and Brown alike stress, is the trick: giving what have come to be referred to as ‘retro-creations’ all the benefits of 21st century automotive engineering, without ending up with an ersatz version of the original beauty that inspired the work in the first place. It’s for this reason that Brown’s Mini, for example, may have more torque than the original, thanks to improved engine management, but it’s no faster: the original may have been nippy, but speed was never its forte, and to give it that quality now would, Brown suggests, be to spoil its appeal. If Minis were noisy - because the driver was so close to the engine - better sound insulation has taken the edge off without, as could be done, virtually silencing it.

Brown compares the difference between his Mini and, say, a mint condition original as that between a Rolex and a Timex watch. “They both do the same thing, but the Rolex does it in a more appealing way,” as he puts it. “Our Mini just feels different to the original - you’re paying for a much higher overall level of experience.”

Of course, it’s the self-same kind of experience that can be found in many cars in 2019 - they’re called new cars. So it begs the question why there seems to be an buoyant demand for retro-creations that provide cars perhaps only on a mechanical par with modern vehicles, rather than superior. But we all know the answer: it’s the look, dummy. For all of the recent efforts of Ferrari, of Aston Martin and other super-car manufacturers, creating a vehicle with the spirit of those of the past is not that easy.

Perhaps time must pass for appreciation to flourish - and this in a world in which patience is in short supply; this is why, as in watches, so in cars, recent years have seen a spate of lazy heritage re-issues, the likes of Ford’s Mustang, Fiat’s Spider 124 or even its Fiat 500. Or maybe, just maybe, there just was something quintessentially cool about the cars of the 1960s and 1970s.

“It was, after all, a revolutionary period of freedom in design, which resulted in some of the most beautifully sculptural products, including cars,” argues Brown. “You know, I had a DB5 for years and, while it’s so fantastic in its style, well, it’s not a great car - it’s too complicated for its time, and yet without the reliability too. I like the look, but, driving modern cars too, I’ve become accustomed to a certain comfort and performance. And I’m not alone in that it seems.”