SPIRITUAL LEADER

He’d joined a sewing circle by the age of four, and by 12 he was learning the art of cutting at a tailoring house in San Sebastián. It’s no wonder that, by the end of his God-fearing life in 1972, Cristóbal Balenciaga was known as ‘the master of us all’.

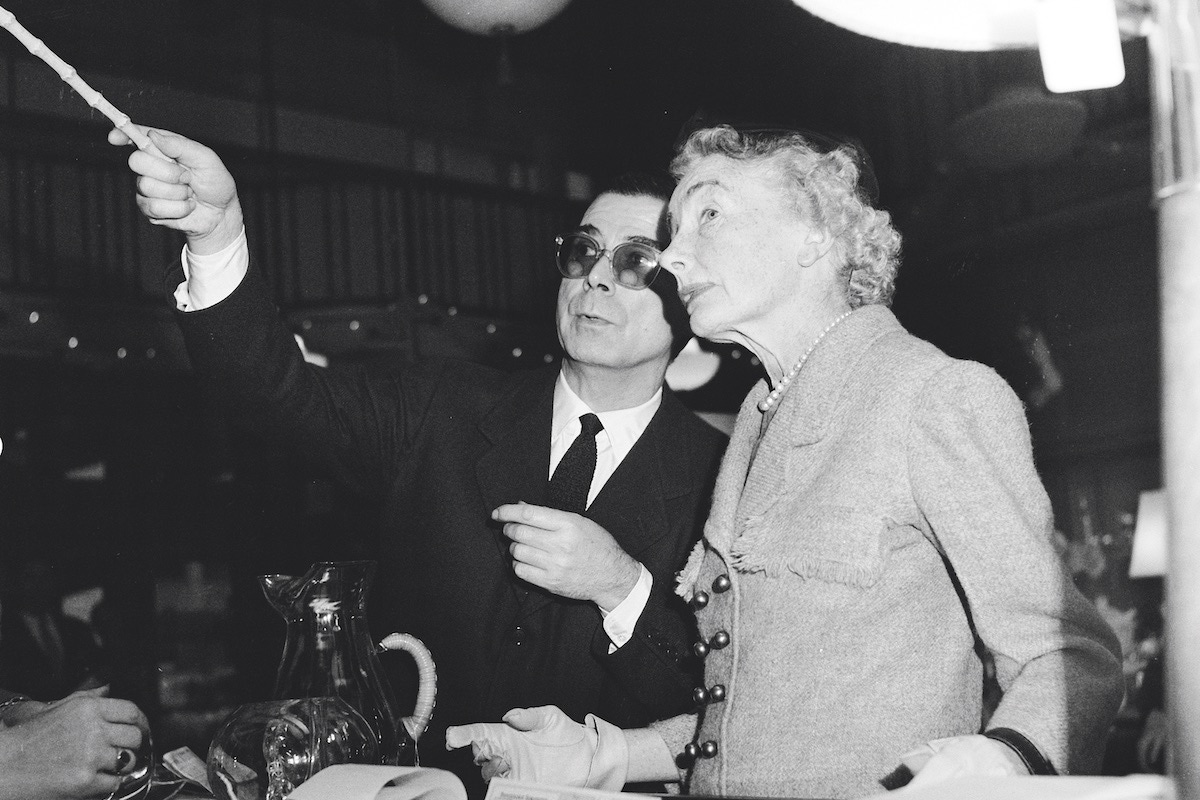

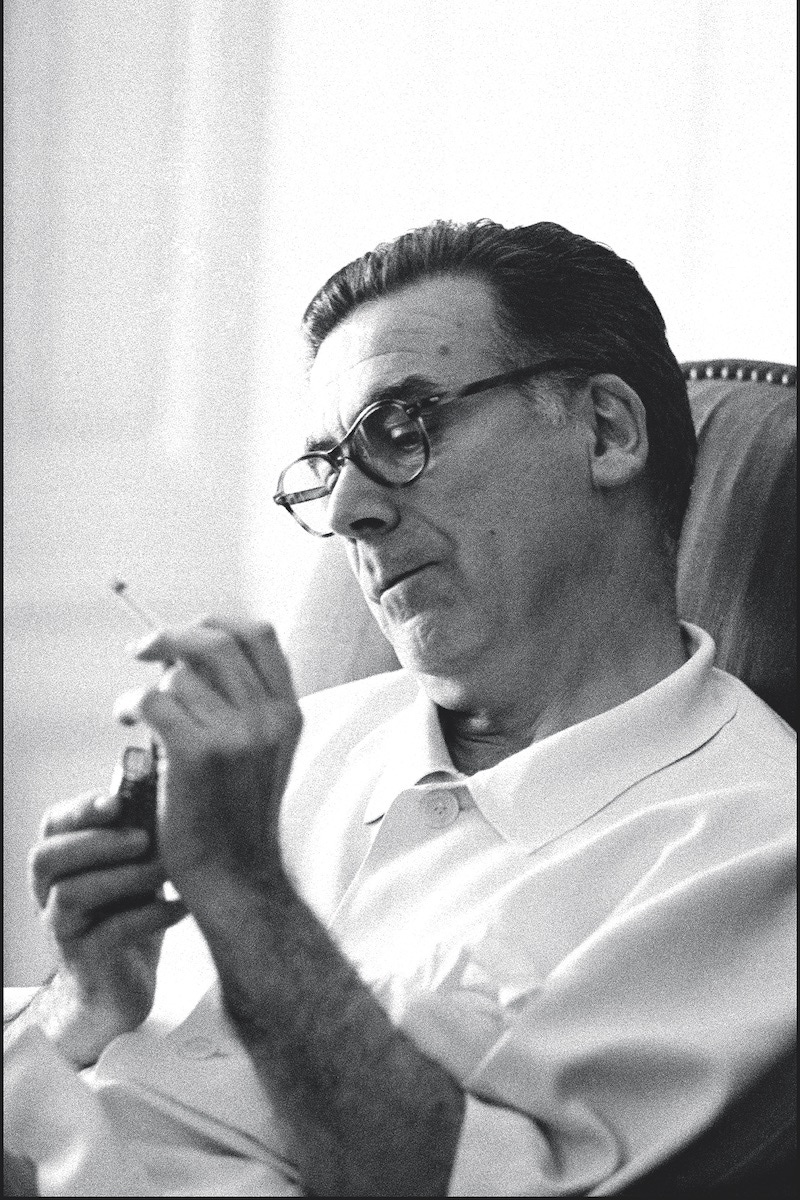

What would the venerable couture house’s creator have made of all this? Hard, if not impossible, to say, as, during his long and illustrious tenure as “fashion’s Picasso” (Cecil Beaton) and “the master of us all” (Christian Dior), Cristóbal Balenciaga made J.D. Salinger look like a blabbermouth. “He is seldom to be seen by his clients and he rarely goes out into society,” Beaton wrote. He gave only one interview, to The Times in 1971, in which he was at pains to express “the absolute impossibility of explaining my métier to anyone”. Only one official photo session exists, from 1927, in which a pensive-looking Balenciaga perches on an Ottoman, resplendent in an immaculately soft-shouldered double-breasted suit and a fluffed pocket-square whose arabesques mimic the avant-garde swirls of his most outré creations.

So we know, at least, that Balenciaga was on more than nodding terms with both the sacred and the profane; Beaton, of course, can elaborate further. “Balenciaga is a raven-haired, stolid-looking Spaniard of middle height and age,” he wrote, “with piercing eyes, hooked beak, and birdlike movements of the head. He is of humble origin, his taste is impeccable, and he expects perfection in all things.”

He was born in a Basque fishing village in 1895; his father was a sailor who died young, and his mother turned to dressmaking to make ends meet. Cristóbal, her youngest child, joined the sewing circle at three and a half, showing “astonishing skill” with the needle (he was ambidextrous, and could cut and sew with either hand). At six, he designed a collar set with pearls for his cat; this was noticed by a grand dame of the neighbourhood, the Marquesa de Casa Torres, who became Balenciaga’s first patron, getting him to copy one of her best dresses. At 12 he was apprenticed to a San Sebastián tailor to learn the art of cutting.

It was this latter skill, honed through frequent visits to Savile Row and an obsession with tweeds and wools and the creation of “the perfect sleeve”, that set him apart from his peers. “He is a tailor and cutter,” wrote Beaton. “He knows as no one else how to make stuff live — to play with material and give it articulation.” He opened his first shop in San Sebastián in 1919; by the late twenties he was running up imperial outfits for Queen Victoria Eugenie and Queen Mother Maria Christina, before the Spanish monarchy’s suspension in 1931. The outbreak of the Spanish civil war forced his transfer to Paris in 1937, to the third floor of No.10 on the new Avenue George V, and while he kept a proprietorial eye on his homeland — to the extent of dressing General Franco’s wife after the Nationalists’ triumph — he made Paris his chief base, alongside his partner Vladzio Zawrorowski d’Attainville (who designed the baroque hats that accompanied Balenciaga’s creations) and business manager Nicolás Bizcarrondo (who also, not incidentally, attended to Balenciaga’s sexual needs). He presented his first collection in August 1937, charging around 3,500 francs for a dress, and quickly picked up a stellar client roster, including the Duchess of Windsor, Countess von Bismarck (who dressed exclusively in Balenciaga, up to and including her gardening shorts), Barbara Hutton, Grace Kelly, Jackie Kennedy (J.F.K. was aghast at the bills), and Helena Rubinstein. They were captivated by Balenciaga’s revolutionary shapes and cuts: “Before Balenciaga, well-dressed women wore a good suit, a blouse, and a becoming hat,” wrote Beaton. “Balenciaga took away the blouse, pulled open the coat at the sides and back of the neck, cut the sleeves between elbow and wrist, thickened the shoulders, let out all seams, and put a dog’s hat on the head. At first, women appeared as if they had escaped from a cataclysm wearing someone else’s clothes, but the provocatively covered forms and loose-fitting slacks, in fact the silhouette of today, were all the invention of this lone mastermind.”

If Balenciaga was, fittingly, the closest fashion got to a religious experience — “Gloria Guinness was sliding out of her chair onto the floor,” reported a breathless Diana Vreeland of one Balenciaga presentation — the feeling was enhanced by the monastic feel of his atelier. While Dior’s premises were busy and buzzy, Balenciaga’s were silent, and guarded by a fierce gatekeeper, Madame Renée, whose motto was Les dames curieuses ne sont pas bienvenue ici.

Not that the place was drab. “The window decorations by Janine Janet were the best in Paris,” wrote the historian Paul Johnson in his book Creators, “featuring birch sculptures of fauns and unicorns. Inside were tiled floors, Spanish-style; oriental rugs; damascene curtains; ironwork fittings; and a great deal of Cordoba leather. The elevator was lined with leather, too, and contained a sedan chair.”

There are very few photographs of Balenciaga at work; those that exist show him in black trousers and sweater, topped with a white lab coat, presiding at a curved table piled with fabrics, rulers and set squares. “He had the manners of an old-fashioned cardinal under Pius XII,” wrote Johnson. “He was sometimes angry, but his anger expressed itself in irritable foot movements; he never raised his voice.” Off-duty, according to Beaton, he lived “an extremely quiet life in a luxurious apartment decorated with the acme of restraint in sombre Spanish taste.”

In a sense, Balenciaga was anti-fashion, finding inspiration in the Spanish old masters – Velázquez’s royals, Goya’s duchesses, and Zurbarán’s saints. No wonder he found the pop art explosion of the sixties more than a little de trop. He dismissed the new breed of designers, like Yves St Laurent, as merely “trendy” (a word that Balenciaga naturally abhorred), and abruptly shut down his atelier in 1968, declaring that there was “no one left to dress”. He retired to his house in Igeldo in the Basque country, “the centrepiece of which”, writes Johnson, “was a vast antique wall table with his mother’s old Singer sewing machine in solitary state, beneath a vast and fearsomely realistic crucifix”. They were his twinned icons, but if Cristóbal Balenciaga could be resurrected, 45 years after his death (admittedly a tall order), and could put aside what Beaton called his “oceanic reserve” (maybe an even taller one) he might enjoy a wry smile at Demna Gvasalia’s updating of his sexy priests with his own sexy execs. Balenciaga, it seems, is still a byword for radical silhouettes, avid experimentalism, and reverent irreverence.

This article originally appeared in Issue 55 of The Rake.