The Congo Sapeurs: A Subculture of Style

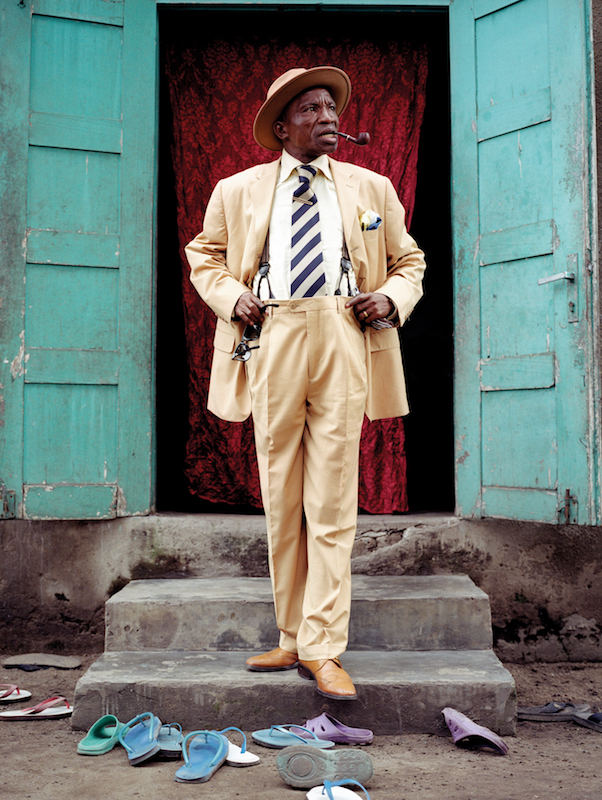

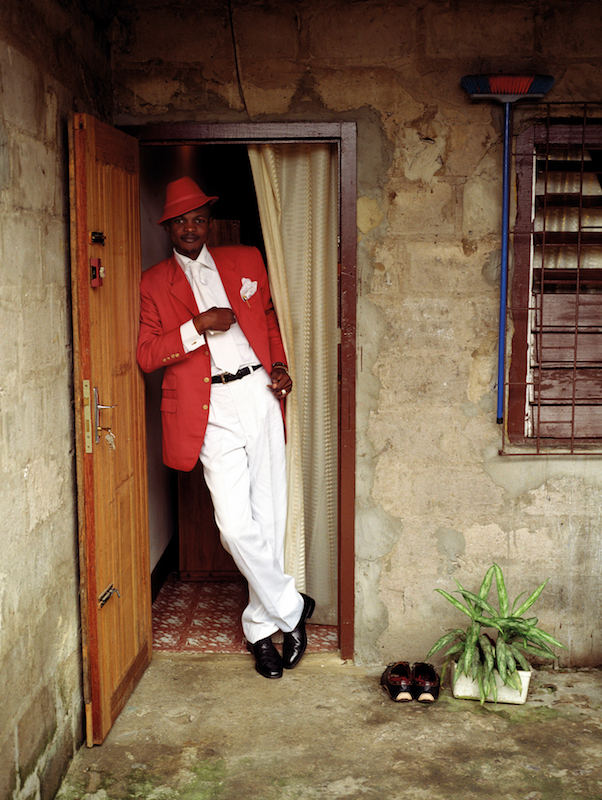

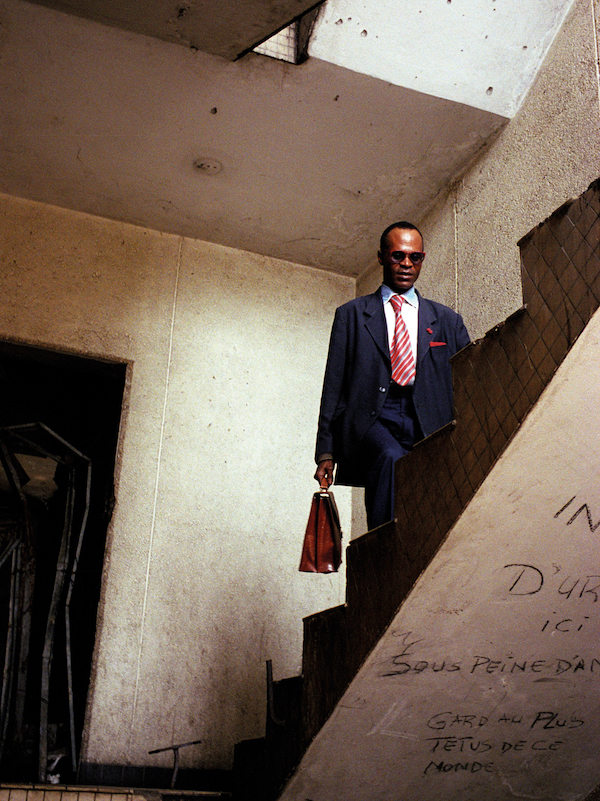

Enter Brazzaville, capital of the Republic of the Congo, and you may be greeted by something of a visual non-sequitur: local gentlemen, decked out in vibrantly hued suits with well-appointed pocket squares and ties, parading on dirt roads or mingling with their peers and puffing away on cigars outside the city’s dilapidated cafés. Their admirers, whose dramatically less refined getups wither in comparison, form clusters around these men, and trail their jaunty steps with covetous eyes.

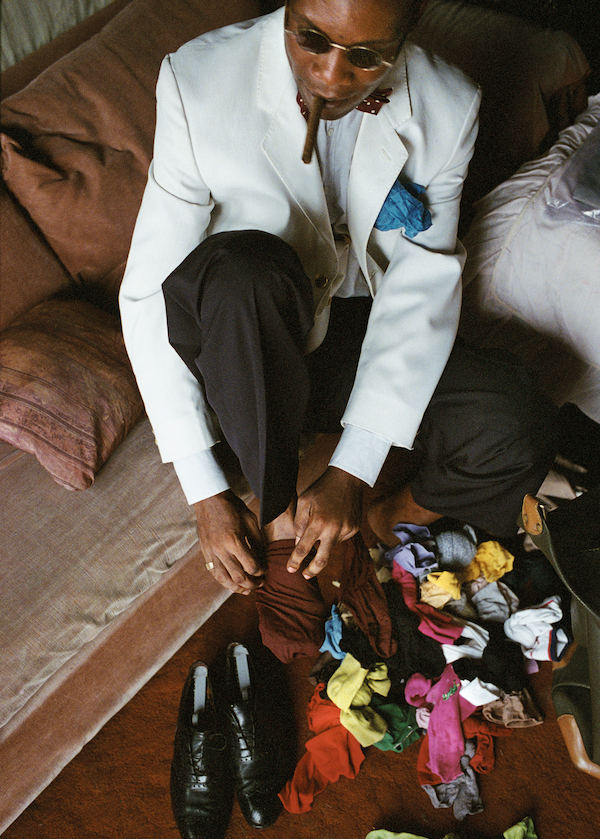

This group of extraordinary gentlemen identify themselves as members of SAPE — or Société des Ambianceurs et Personnes Élégantes (Society of Ambience-setters and Elegant People). Nicknamed ‘Sapeurs’, their mission is to promote sophistication in a country blighted by civil war and austerity. Observers might assume these characters are successful businessmen, but the Sapeurs are often either unemployed or engaged in everyday jobs — driving taxis, manual labour and so on. And, this is no elite club: anyone is allowed to join, as long as they dress the part. The only obstacle is the cost — the price of a new old-school European menswear ensemble may very well amount to a year’s income in this part of the world.

Historically, the Sapeur movement can be traced back to 1922, when ‘Grand Sapeur’ G. A. Matsoua invited widespread ridicule by becoming the first-ever Congolese man to return from Paris dressed like a French dandy. Later, in the 1970s, the Congolese ‘King of Rumba Rock’ Papa Wemba, inspired by haute couture in Paris to revive the stylish attire of his former colonisers, championed an extravagant dress code which was in direct opposition to the dictatorial decree of Mobutu Sese Seko. This forbade men from wearing Western attire to symbolise the country’s break from its colonial past; instead, men were encouraged to wear the national costume, the abacost — a short- or long-sleeved button-up jacket with a high collar, worn without a shirt.

The only instance of a shirt and tie symbolising rebellion? Possibly so, but there is more to the SAPE movement, quite literally, than meets the eye. There’s something very dignified and uplifting about these men taking such a colourful stand in the face of adversity. It’s no surprise their incongruity with their milieu has brought them fame, and that the movement is thriving. Nowadays, young Sapeurs assemble regularly to flaunt their latest accoutrements, while the older generation are more likely to suit up simply to feel inwardly good. After all, sartorial elegance is not only the raison d’être of Sapeurs — it’s also their escape from the grit and grind of everyday life.

Originally published in Issue 23 of The Rake. Subscribe here.