How Giorgio Armani Redefined Menswear

“Sartorially speaking,” Martin Scorsese once said, “there is BG, before Giorgio, and AG, after Giorgio.” This, from a man who didn’t even direct the movie which made it all happen…

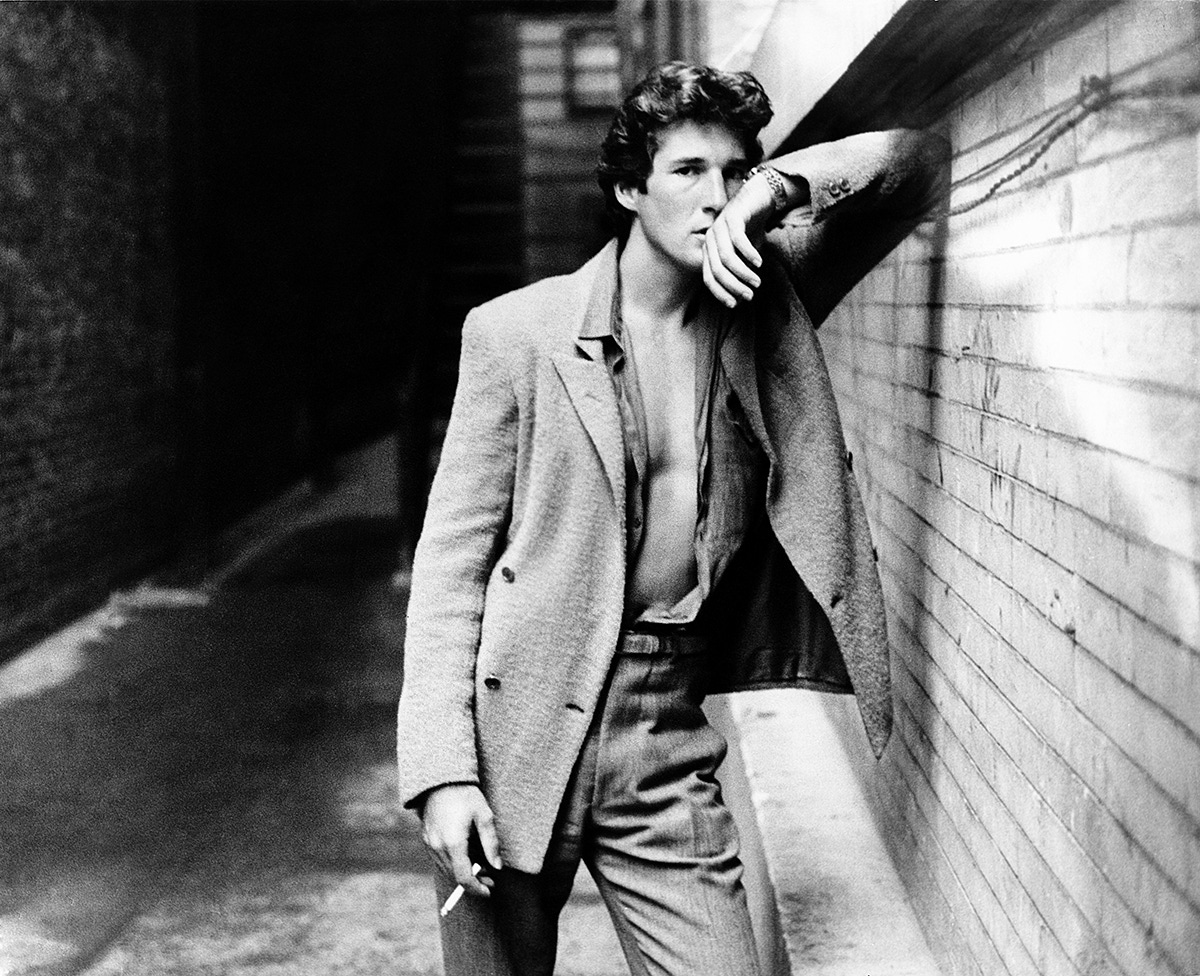

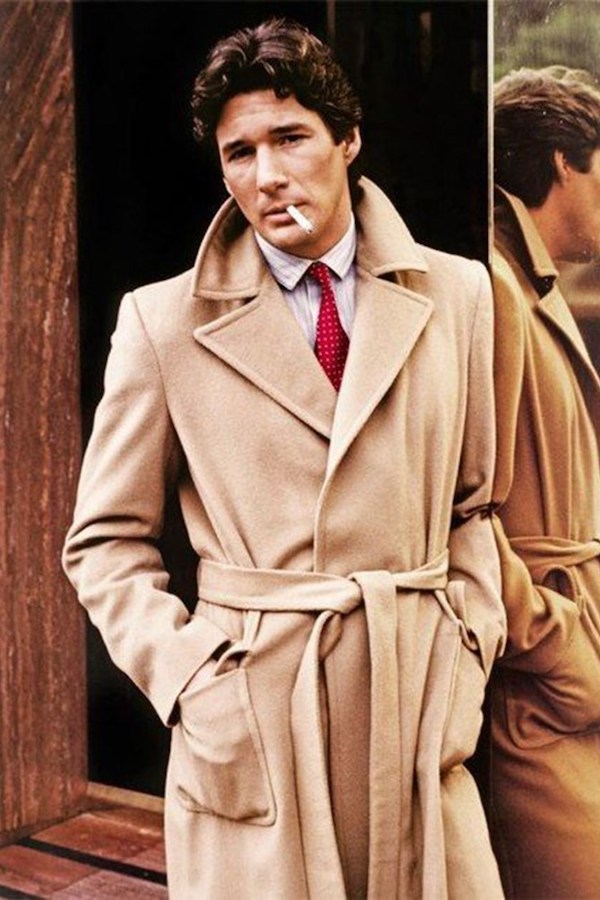

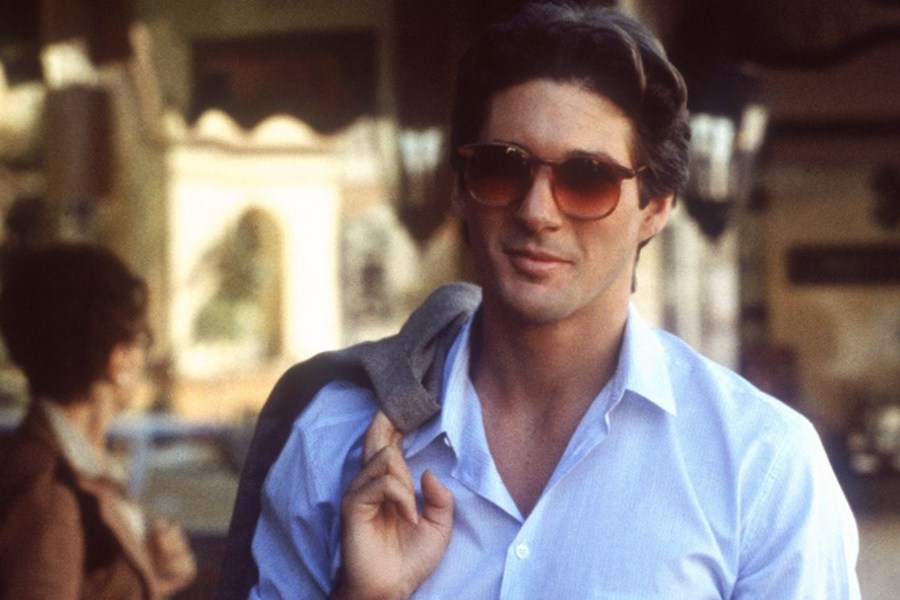

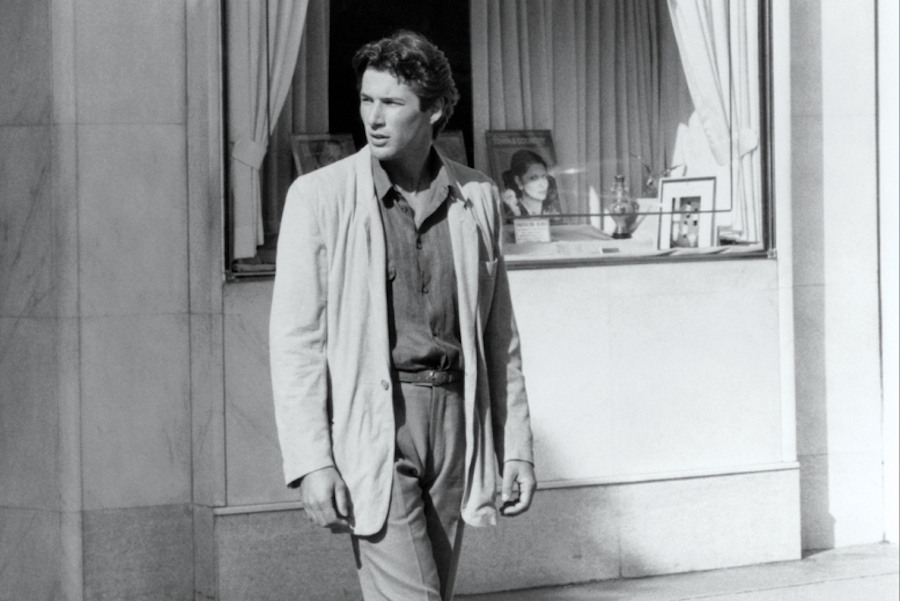

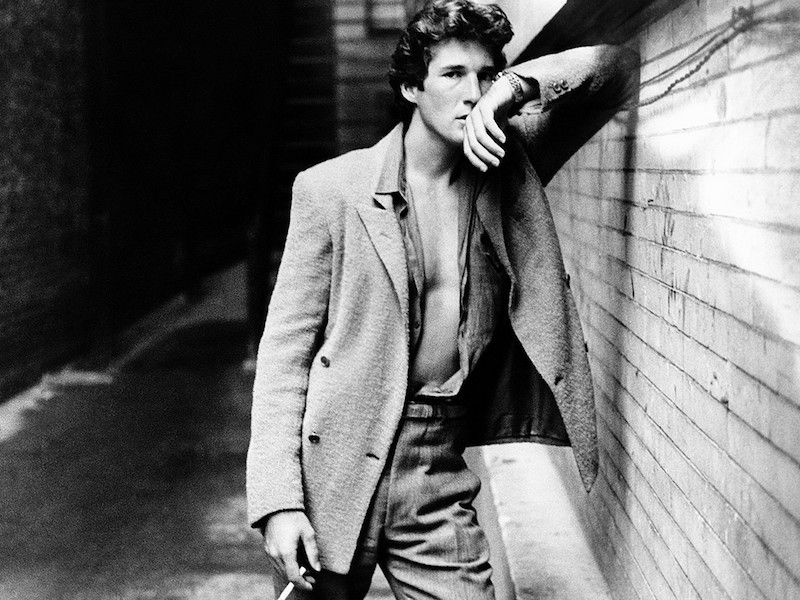

The moment American Gigolo director Paul Schrader trained his crew’s cameras onto Richard Gere’s Los Angeles male escort laying out his suits on his bed, while dabbing cocaine off a mirror and singing along to Smokey Robinson, menswear underwent a seismic shift. But the man responsible for the up-to-11-and-a-half Richter scale vibrations caused by American Gigolo was neither Schrader or Gere, but actually a man born into an Italian-Armenian family in the northern Italian town of Piacenza some 36 years prior to the movie’s release, and who found his way into fashion, following a stint in the armed forces, via a role as a window dresser in a Milanese department store.

It’s impossible to overstate just what Armani did for menswear in the 1980s. One might just, without getting a kick in the Jacob’s for lazy hyperbole, suggest that he sexed up men’s wardrobes early that decade in the same way that Deep South blues sexed up rock and roll music half a century earlier. And the core of his strategic masterstroke was the frontier dividing casualwear and formalwear.

Giorgio Armani wasn’t the first to see heavily structured clothes as inherently constricting – to note that their angular-linear silhouettes were dignified and imposing yet far from debonair and insouciant – and act on the problem. Frederick Scholte – mentor to Per Anderson of Anderson & Sheppard fame, and tailor to the Duke of Windsor – invented the British drape in order that clients might trade rigidity for fluidity, while around the 1930s, the most esteemed tailors of Naples – notably Rubinacci – began eliminating linings, canvasing and pads from their coats to create garments better suited to la dolce vita than a stiff appointment at the city’s Royal Palace.

But no one post-war has done more to transform male dress codes – and not just what men wear but, crucially, what they might be allowed to wear – than a then little-known Italian designer whose name now is among the most prestigious clothing brands in the world. Bolder colours were a big part of his revolt. Lighter fabrics including bouclé, flannel and crepe also played a huge role. The lowering of the buttons removed even more of the military sanctimony of traditional suiting. But it was those cleaner, more fluid lines that fuelled a kind of bloodless coup: one which didn’t so much tear the barriers down between formal and casual as expose the distinction as fictitious – chimerical, forced and entirely corrosive to post-war male elegance. In doing so he re-wrote the codes of masculinity forever.

“He has an incredible sensuality and wears every look so naturally, so he was a pleasure to dress,” Armani has said of dressing Gere in what turned out to be his first of over 200 involvements with movie wardrobes, over which he’s made the link between cinematic costume and character inextricable. “I was motivated by the desire to modernise menswear - in the field of men’s clothing we were still tied to more or less the same clothes our fathers and grandfathers wore. I wanted to use softer fabrics and rethink the suit, getting rid of most of the linings and fillings. The unstructured result was a truly new look that preserved its precision while becoming more body-conscious and more comfortable.”

Other movies styled by Armani include The Untouchables, Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy and Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, the latter in particular – think pronounced shoulders, oversized lapels, wool-blends, pinstripes, dark greys and V-shaped virility, as befitting of early ‘90s alpha males – showing his versatility when it comes to making on-screen attire contribute as much to character, era and narrative nuance as any script writer. But American Gigolo is the one that threw down a gauntlet. When it comes to sartorially relevant movies, it’s hard to think of one which looms larger in post-war history (Shaft, Blowup and Quadrophenia are all a little too niche to be deemed sartorially seminal, while 8 ½, Bullitt, Reservoir Dogs and Oceans 11 et al are all up there, but didn’t exactly dismantle and rebuild the fashion mores of a whole generation).

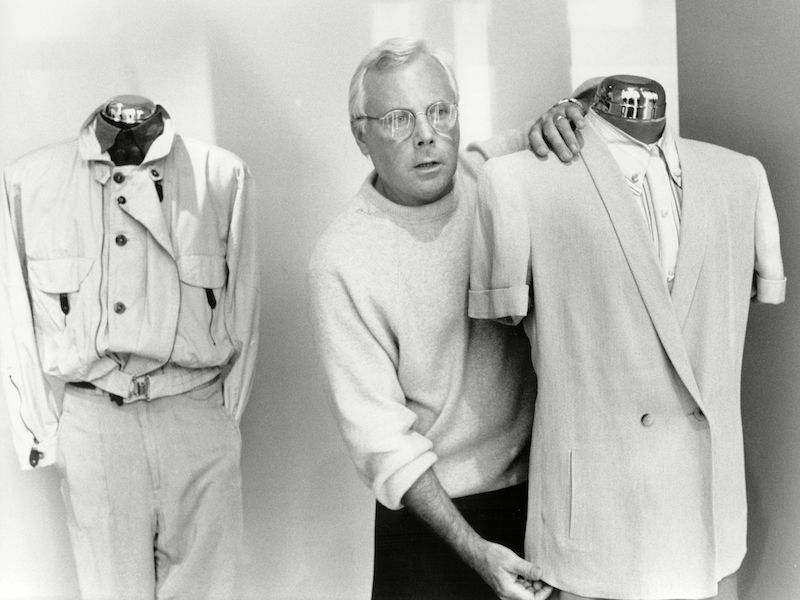

Now aged 83, the Great Man’s achievements are legion. He’s confounded fashion purists’ addiction to the transient with unswerving focus on a set creative route, which puts wearer before designer (“I try to be coherent, consistent and as democratic as I can,” he recently told The Times). From a commercial perspective, he’s the founder, chief executive, designer and sole shareholder of a brand worth perhaps $7billion, which employs 7,000 people and has 2,500 branded outlets. But it’ll be hard for Mr Armani to ever top that extraordinary feat of making men comfortable buying and wearing breezier, more fluid but no less elegant clothing.