Into The Fold: The Pocket Square

The pocket square merges purity of form with nearly unlimited creative possibility. But where did such a uniquely stylish accessory come from? And how does one truly master it?

Has ever such a simple accessory brought as much to an outfit as the humble pocket square? Little more than a square of cloth with a rolled edge, potentially - but not definitively - featuring some kind of design. And yet it’s so much more. It can break up a sombre outfit or tie together a disparate ensemble. It can add a hint of texture or a swell of colour and pattern. It can show refinement or flair - often both in equal measure. Unfurled, it can reveal a work of art.

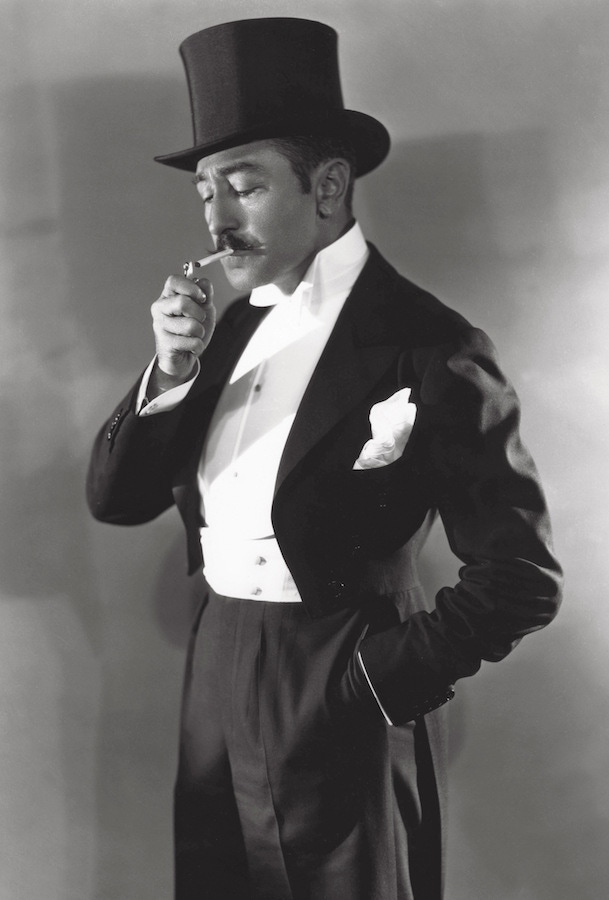

It wasn’t always such a glamorous life for the pocket square, or handkerchief. Its earliest ancestor - small squares of linen or silk first referenced around 2000BC - would be dipped in perfume and used by the wealthy to avoid the more unpleasant scents of the urban living of the day - a practice recorded across Greece, Egypt and the Middle East. Their use persisted into Rome, primarily as accoutrements to the rich. Gladiators would march the exterior of Rome’s Colosseum before matches began, halting in front of the emperor to proclaim "Ave Caesar, morituri te salutant" - "Hail Caesar, they who will die, salute you." The emperor would then produce a pocket square - the orarium - to signal the match’s commencement.

King Richard II is generally credited with the invention of the ‘handkerchief’, although its function was essentially the same - a linen square for him to wipe his nose with (an ongoing issue for the poor king, apparently). Swiftly adopted by the populace, it became a common sight in Britain and Europe over the next century, used both for wiping or covering the nose as well as for adornment. Knights would wear a lady’s handkerchief as a symbol of their favour during tourneys and the nobility would carry elaborately laced squares as signs of wealth. They found great popularity in Italy during the Renaissance, especially with women. Drawing a square - called fazzoletto at the time - across one’s cheek in conversation would signal an unspoken desire, whilst drawing one through one’s hands signalled revulsion or resentment. Women of the upper class seeking to, shall we say, enhance their assets would sometimes use their handkerchiefs to add extra volume to their bodice. This handkerchief stuffing, however, had a tendency to move about, creating some uneven and decidedly less than natural curves over the course of a day’s wear.

The Ottoman Empire of the 1800s introduced woven linen and cotton squares known as mendil. Mendil were originally religious in nature - on holy days, mendil rubbed on Prophet Muhammad's holy mantle were believed to bring abundance and good fortune, and were given as gifts to visitors. They also were common accessories with the populace, and their gifting formed part of a coded lover’s language. Notably in the context of modern pocket squares, these frequently featured embroidered designs or edges, or solid colours with contrasting coloured borders. Different colours or trims represented different messages that could be passed - white meant ‘I love you’, whilst the dreaded blue trim meant ‘you are not grateful. I am in sorrow.’

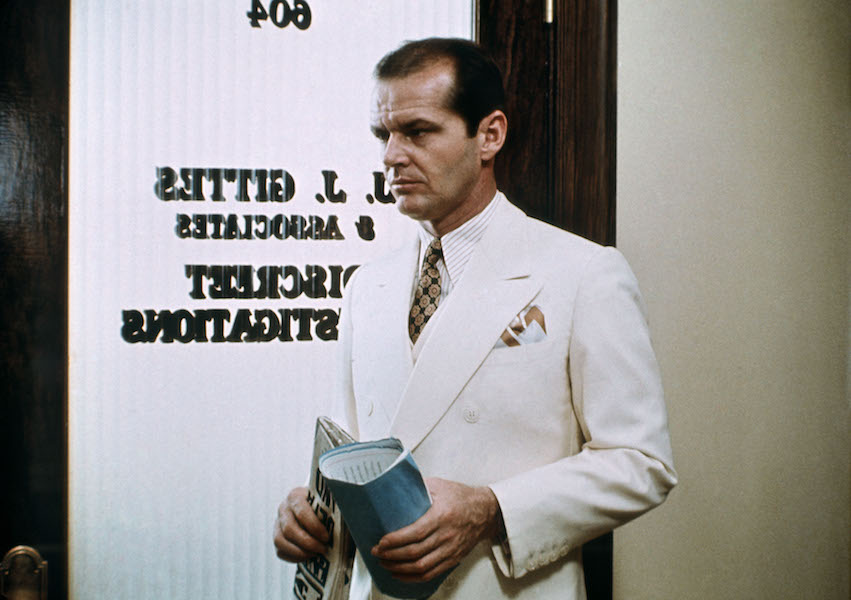

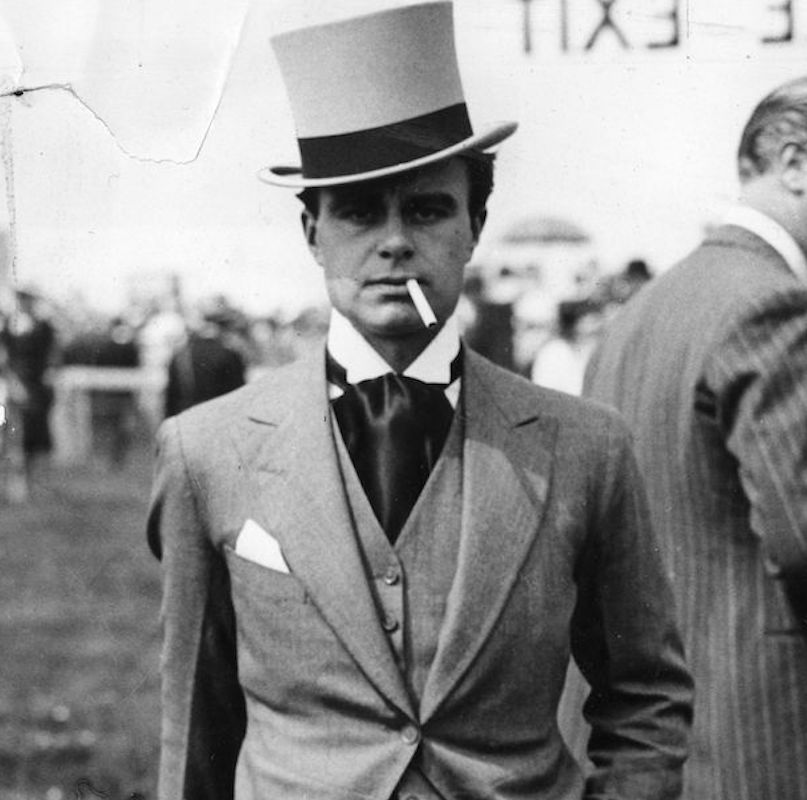

It wasn’t until the 19th century that the square became an accessory of the pocket, brought about by the popular ascent of the two-piece suit. To avoid their handkerchiefs being dirtied by coins in their hip pockets, men began carrying them in their breast pocket, often with the odd corner peeking out. Once again, this purely practical choice became synonymous with the style of the well-heeled. It became common for men to wear a square in their breast pocket purely for looks, whilst carrying a second in a hip or internal pocket for practical purposes.

20th century developments in silk printing enabled designers to add more intricacy and detail than ever before. Allied fighter pilots in the Second World War would often carry a handkerchief or silk scarf printed with a map of enemy territory. Unlike a paper map, silk wouldn’t suffer from creasing or water damage, and could be easily concealed. Silk printing also opened up a world of possibilities for pocket square design - possibilities designers in the second half of the 20th century eagerly explored. Makers began to see the small, decorative square for what it had the potential to be - a canvas, a piece of art.

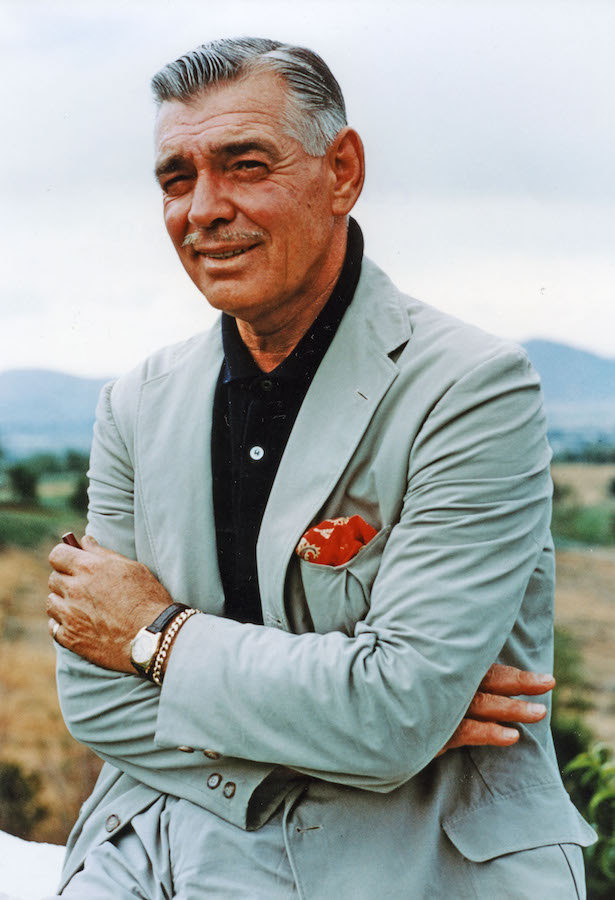

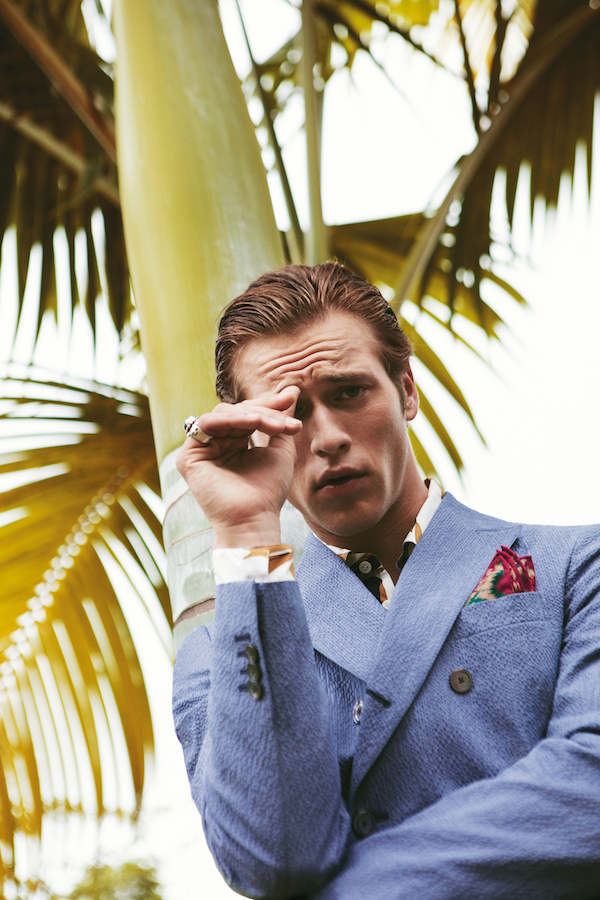

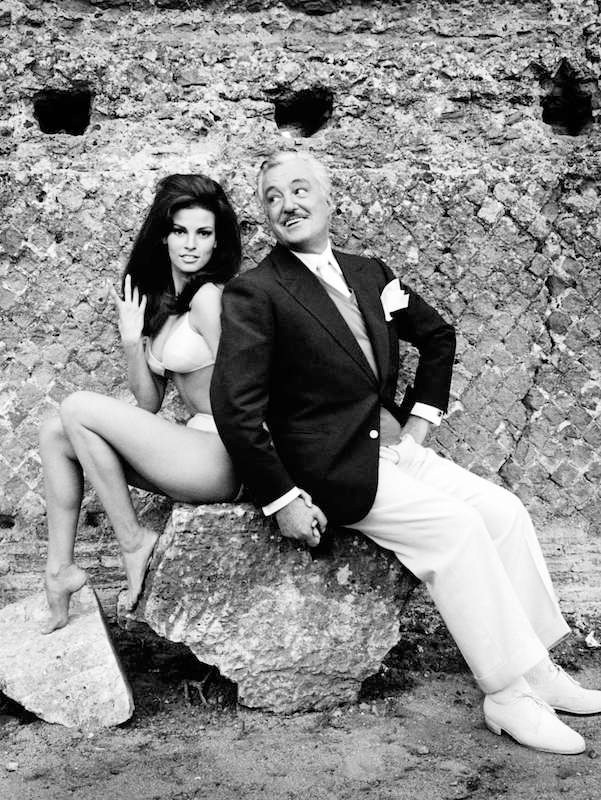

Today, the pocket square has taken its rightful place as a stalwart accessory of the elegant, the ostentatious and the just plain interesting. A plain silk, for obvious reasons, remains one of the most popular variations - perfect for accenting suiting or eveningwear. Spring for a coloured border if you can - with most outfits, bar black tie, the secondary hue adds a smart touch of contrast when worn with the edges out. Printed silk can take on any number of forms - from the indulgent Neapolitan elan of a Rubinacci number to the offbeat Britishness of an Edward Sexton square, truly anything can be possible. The central design is important, but pay as much or more attention to the border and trim - frequently these are the parts most seen. A plain or bordered linen is a great choice with seasonal separates, both in summer and winter. For colder months, wool and silk blends offer a great mixture of drape, rich colour and and a tactile handle - perfect for pairing with more robust tailoring or winter tweeds.

When choosing your square, there is one cardinal rule: it’s not meant to match. Find one that prominently features a secondary colour from your tie or your tailoring, even your sock, but avoid directly copying anything primary. Squares look best worn either puffed or with the edges out. The flat ‘TV fold’ should be relegated to TV - it’s neither elegant nor practical and it’s a complete bastard to keep looking good. Don’t fuss to much about making your square look perfect or neat either - a certain devil-may-care attitude goes a long way. And have fun with it. After all, it’s just a decorative square of cloth, right?