Riot Gear: Punk Sedition & Sartorialism

Tracing punk’s path from the slums of London and New York to the runways of Paris and Milan.

Across the street from where I once lived in London’s Bayswater, punk history was made. Unlike the nearby Orsett House — which bears a blue plaque attesting to the ‘father of Russian socialism’, wealthy exile Alexander Herzen, having resided in the grand stucco villa in the 1860s — there’s nothing to commemorate the particular moment. But in 1976, Joe Strummer of The Clash, The Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious and The Slits’ drummer Paloma “Palmolive” Romero spent an extended period living together in a derelict squat at number 42 Orsett Terrace. It’s not merely this trio of notable residents that make the address remarkable — there’s also the fact that it was here, beside the Westway, where Strummer penned the seminal ‘London’s Burning’, while shivering in an unheated top-floor room.

Today, musical seditionaries no longer illegally doss in Orsett Terrace’s Grade II heritage-listed townhouses. Originally built as urban residences for the landed gentry in the early Victorian era, before falling into neglect and becoming slums in the punk epoch, these homes have long since returned to the hands of the privileged few. A one-bedroom flat in ‘Champagne communist’ Herzen’s erstwhile gaff recently changed hands for £1 million. The chap living in 42 during my time on Orsett Terrace, some 14 years ago, would be picked up each day in a chauffeured Mercedes, and take off for his country place in a shiny Porsche 911 every weekend. The street’s been gentrified, commoditised and thoroughly luxed up. Much like the musical form Vicious, Strummer and Palmolive helped pioneer — and its attendant stylistic tropes.

The ripped ‘n’ thrifty punk aesthetic — what Television co-founder Richard Hell called its “patchy raggedness” — originated quite naturally as a result of early punks’ lifestyles. Eeking out an existence on extremely limited wages or meager unemployment benefits during a harsh recession necessitated second-hand shopping and wearing clothes until they were falling apart. Explaining the origin of that punk perennial, the safety pin, Johnny Rotten once quipped that they’d initially just been deployed as the quickest, easiest means of stopping “the arse of your pants falling out”. Messed-up bed-hair? Crashing on the floor of an unfurnished squat will do that to you. Equally, many of the punk progenitors were art students, and the DIY ethic of their personal style — cutting, ripping, stenciling; self-haircuts, self-tattooing, self-harm; hand-scrawling epithets, profanities and slogans on garments, et cetera — echoed Dada, Surrealism, Postmodernism and the French Situationists, even the Pop Art of Warhol (though Andy’s commercialism was of course anathema). The purposely shocking adoption of Nazi and Communist iconography was done with the intention of alienating the previous generation, (which had lived through World War II and was in the midst of fighting a Cold War), just as successive artistic movements so often seek to make a drastic break with the conventions of those that have gone before them.

The naturally occurring and the contrived. The artistic and the anarchic. The eminently sellable yet anti-commercial. The carefully crafted but haphazardly DIY. All these elements coalesced at the Chelsea boutique run by the grand dame of punk design, Vivienne Westwood, and her then partner in life and business, Malcolm McLaren. Initially a Teddy Boy rocker-wear shop, in 1974, the duo rebranded their premises on the King’s Road to carry the moniker ‘SEX’ above its door, stocking on its shelves a range of audacious studded leather, bondage trousers and latex fetish-wear alongside Westwood’s own provocative designs. For a time SEX outfitted US punk pioneers the New York Dolls, and in 1975, McLaren began advising members of what would become the Sex Pistols on matters sartorial, musical and self-promotional. In 1976 the shop rebranded once again, as Seditionaries, purveying a line of instantly iconic T-shirts bearing such charming prints as the word PAEDOPHILIA, Nazi swastikas and images of naked cowboys. The following year, punk reached its popular peak with the headline grabbing, “fascist regime” smashing release of the Pistols’ ‘God Save The Queen’ from their Never Mind the Bollocks album.

In late 2016, 40 years after the release of the Sex Pistols’ debut single, ‘Anarchy in the UK’, McLaren and Westwood’s son Joe Corré ritualistically burnt the vast collection of punk attire and memorabilia he’d inherited and collected over his lifetime. Lighting a bonfire valued at between £5 to £10 million, Agent Provocateur founder Corré said, “Punk has been castrated and neutered by the corporate sector and the state. Hung, drawn and quartered.” Cheered on by his mother, and in the belief that his late father McLaren, who died in 2010, would have applauded the fiery protest — “He would probably have been proud of me and think it’s hilarious” — Corré said, “Young people today, angry youth, need real solutions, not the now conformist, sanitised and sterilised uniform of punk. It has no currency any more. Punk has lost all of its bite.”

Similar remarks were made by certain observers of the 2013 exhibition Punk: Chaos to Couture at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where original punk garb and footage of Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten were shown alongside contemporary takes on punk chic by the high-priced, high-fashion likes of Alexander McQueen, Martin Margiela, Hussein Chalayan, Rodarte, Junya Watanabe, Ann Demeulemeester, Comme Des Garcons and Chanel. Oddly, given that punk was initially such an aggressive, testosterone-driven scene, the exhibition mainly featured women’s wear. Ornate frocks illustrated how luxury fashion has long co-opted punk’s “aesthetic of violence”, integrating elements such as rips and slashes, studs, spikes, zips, safety pins and razor blades to appropriate punk’s DIY, bricolage aesthetic and anti-establishment attitude into clothing made for the haute bourgeoisie — precisely the group punk’s more politicised protagonists so fiercely opposed.

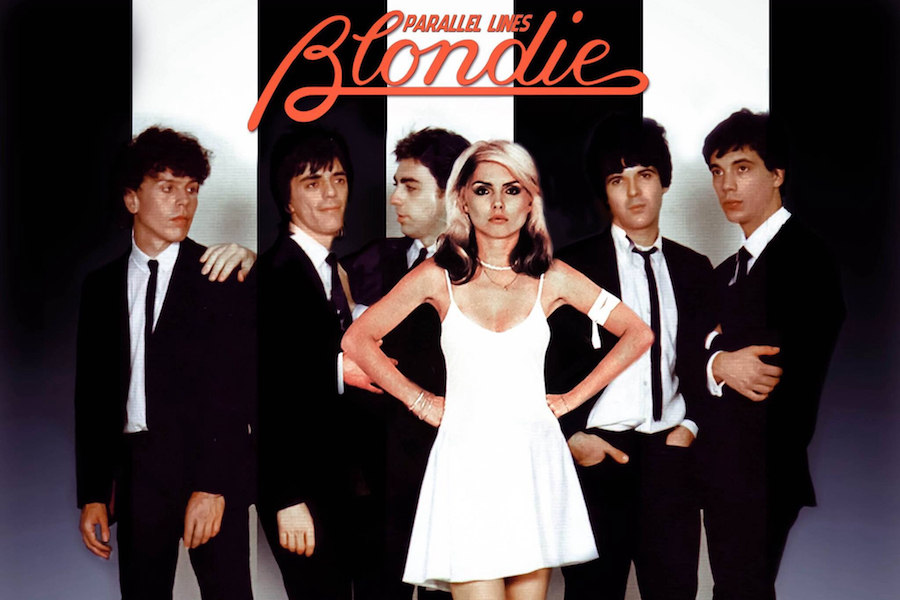

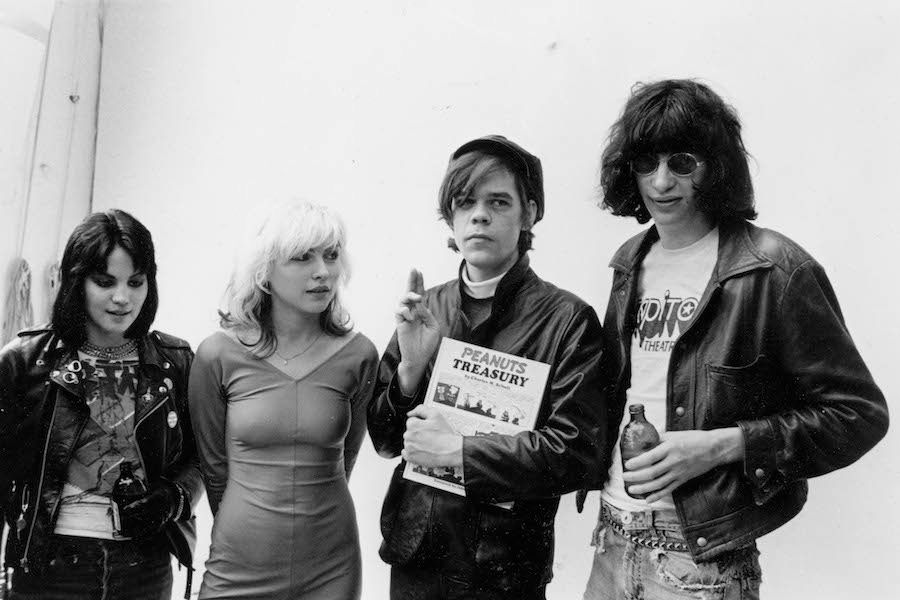

Punk’s impact on modern-day menswear, meanwhile, can be seen most vividly in the work of Hedi Slimane, whose underground rock-inflected skinny-fit styling in the early aughts at Dior Homme and latterly, Saint Laurent, has been arguably the most influential force in menswear this century. Hedi’s leather-and-denim looks unashamedly channel The Ramones redux (and luxed up), while the quintessential Slimane suit — black, slim-fit, with stingy-collared white shirt and narrow tie — is basically a recreation of the outfits worn by New York New Wave fusionists Blondie on the cover of their Parallel Lines LP. CBGB, the scuzzy Bowery slumland club where — among countless others — Blondie, The Ramones, Patti Smith, Richard Hell’s Voidoids and Television, The Misfits, and Talking Heads cut their teeth, is now a John Varvatos boutique, selling artfully distressed two-grand biker jackets. Original, authentic Westwood Seditionaries T-shirts go under the hammer on eBay for even greater sums, their rarity only increased by Joe Corré’s burn-off. And despite the naysayers’ incendiary protests, punk continues to be endlessly referenced on the runway. Notable and covetable examples from the recent top-end menswear collections included Alexander McQueen (showing padlocks, extended shirtsleeves, safety pins and profuse piercings for AW17) and Louis Vuitton (with mohair, tartan, studded collars and subtle bondage trousers in SS17).

On the edgier level, and perhaps truer to punk’s egalitarian, DIY yoof roots, up and coming British labels Art School and Charles Jeffrey Loverboy each brought a gender-bending sense of punky SEX to their 2017 London Fashion Week: Men’s outings. Her son might object, but we think Ms Westwood would be proud of these stylistic heirs. It’s true: punk’s not dead. Not by a long shot. Like those million-quid former Bayswater squats, it’s just gotten more polished and pricier.