Song of Himself

The birth of the Pierre Arpels watch.

At first, Walt Whitman's most seminal poem had no title. It was simply referred to in his book, Leaves of Grass, from 1855, as 'Poem of Walt Whitman, an American'. But as the poem gained traction and significance; as it grew to define a generation in search of identity amid a world divided between nature and industrialisation, between history and modernity, Whitman decided to change the title to 'Song of Myself'. And it is in this poem that he penned the phrase 'I am large, I contain multitudes', six words that a century later would also serve to express the multifaceted nature of one of the 20th century's most significant icons of style and elegance, Mr. Pierre Arpels, who was born into the legendary jewellery firm founded by Alfred Van Cleef and his father-in-law, Salomon Arpels, in 1896. Because in attempting to encapsulate Pierre Arpels, one quickly faces the descriptive limitations of the English language. He was so many things: a flâneur and an entrepreneur, a gifted designer and creator, a sportsman, a dandy, a moralist and an adventurer. He was the architect of the firm's modernity amid a rapidly changing world, even while he was its conduit for the tradition of haut de gamme gem-setting and jewellery design. In many ways, Pierre Arpels was the ultimate lightning rod, the amplifier of the zeitgeist of the times he lived in, transmitting its prevailing social mores, and refracting the ever-heightened tension between past and future through his special creative ability. He was a constant traveller in a rapidly internationalising world where the jet set and the Café Society had merged into one nonstop global parade of exuberant experiences, and innumerable nights and days of immeasurable grandeur.

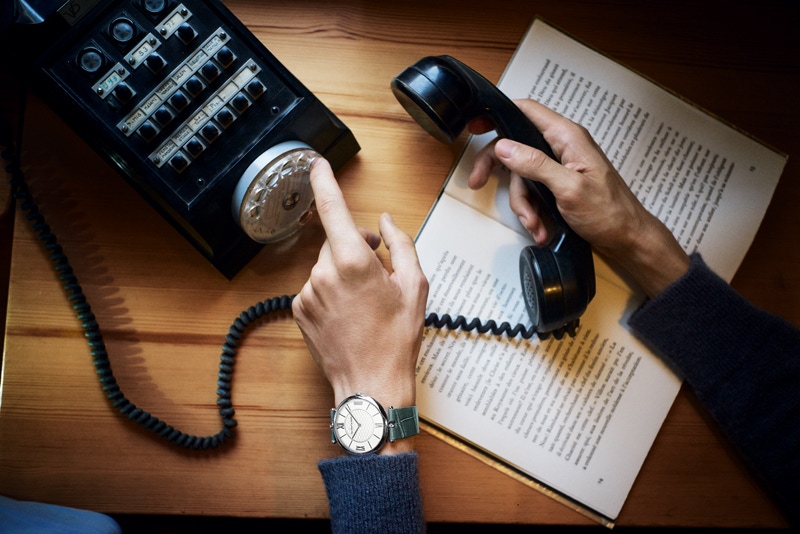

One thing that's certain is that Pierre Arpels was inextricably linked to the fabric of the haut monde of the time. But he achieved this while always remaining understatedly graceful, and even self-effacing. He was very much a man who let his fabled creations speak for themselves, but his achievements amid the haut monde were incomparable. It was he who escorted the maison's legendary diamond diadem to Monaco, for it to be worn by Princess Grace at the Monte-Carlo Centenary Ball in 1966. It was he who travelled to Iran to receive one of the maison's most historically significant commissions - the jewels and crown created for Empress Farah Diba. He created breathtaking pieces for the revival of George Balanchine's ballet, Jewels, while introducing prima ballerina Suzanne Farrell to the world of his jewellery.

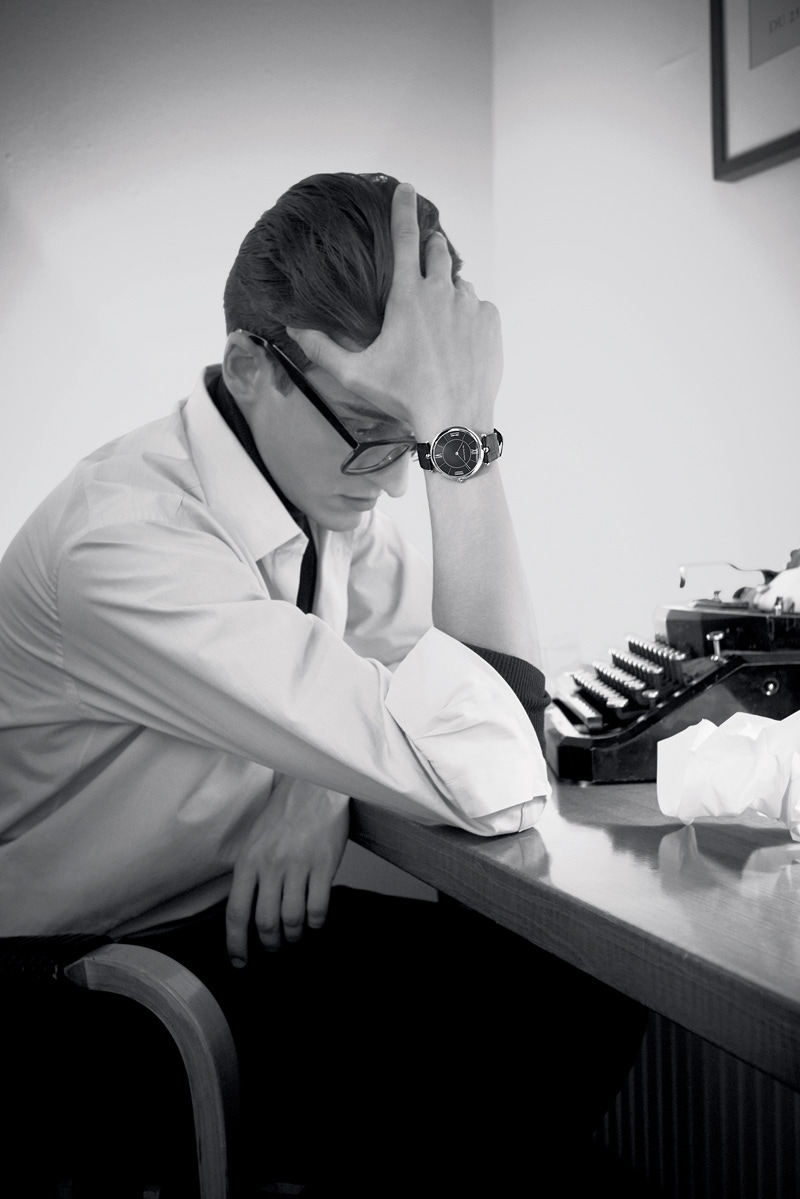

And, all this time, his one trusted companion - helping him subtly chart his progress from day to day as he traversed the globe, and serving him faithfully and unerringly - was his timepiece. It was this watch that could be said to be his most deeply personal creation. He designed it in 1949 as a reflection of all that he felt a timepiece should be: a vivid, salient expression of his internal vision for elegance - what Proust called 'the revelation of a particular universe which each of us sees and which is not seen by others'. But let's look at it in context. At Van Cleef & Arpels, he had come out of the dark years of World War II and he was left with a sense of seriousness, a desire to strip away artifice and explore the pure, essential nature of forms. Indeed, had he not remained a jewellery designer, he would have likely forged a career as an architect. Sitting in repose in the Japanese Zen garden he had constructed on the top of his Paris apartment, he began to imagine the perfect watch. A watch that, as in Plato's analogy of the cave, turned our eyes away from the distracting, ephemeral shadows cast on the cave wall and sought out truth as its own form of divine beauty.

Of course, it started with a perfect circle: the ultimate expression of harmony and infinity, a line without beginning or end. In the Feng Shui philosophy, the circle is the heaven for the spirit; accordingly, Arpels imagined it as the repository for a very special kind of movement that was an expression of the most ambitious technical watchmaking of the day. Specifically, Arpels wanted an ultra-slim movement for his watch. With the advances in watchmaking, movements had become thinner and thinner, allowing designers to create ever-sleeker expressions of elegant timekeeping. But for Arpels, the thin case had another purpose beyond the aesthetic, which had to do with his own sense of morality - that of his impetus for ultimate discretion. It was profoundly important for Arpels that the watch shared an intimacy with its owner, the person imparting life unto it by winding it each day.

But more so in Arpels's perspective on harmony and elegance, a watch could never be a trophy, or an aggressive symbol of status or affluence. Time itself should also not be allowed to dominate life and rob it of its extraordinary capacity for spontaneity and joyfulness. Arpels would consider it the tragic apogee of poor taste to be caught looking at his watch when in the company of friends or clients. It is for this reason, above all, that his watch had to be extra thin, so as to slip in and out effortlessly from underneath his shirt cuff, without ever being impeded by the material. Arpels would not condescend to fidget with his cuff barbarically - the act of checking the time had to always appear nonchalant and effortless; it had to be a physical haiku in its sparse economy.

The dial of his watch would similarly express a startling and thoroughly modern reductionist simplicity, with an array of precisely placed Roman numerals, and, unexpectedly, a precise minute track at the dial's perimeter. And, perhaps, these elements hinted at the dichotomy that existed in Arpels as it does in all men, simultaneously elegant and capable of the most reverent dreams and dazzling creations, yet also rooted in order and precision. The precision that Arpels encoded into this most personal of timepieces also reflected a changing world, one in which modes of transport were rapidly evolving, and with them the way in which soceity would remake itself according to the transcontinental collective consciousness of a new Jet Set age. Modernity beside craft, science beside art - these elements all merged within the Pierre Arpels watch, evisioned by a man saliently tapped into the zeitgest of his era.

But it is perhaps the Pierre Arpels watch's attachments that are the most personal stylistic flourish of its creator. Because, Arpels's search for beauty had led him to arrive at a concept for a watch that had no lugs, and that was fixed to two horizontal elements for retaining the patent alligator strap, using two tiny lateral elements located at the top and bottom of the watch - reminiscent of the central axis that runs through the Earth from one Pole to the other. The result is the illusion of a case that seems to float between the straps affixed there as if by nothing more than the sheer force of its own will.

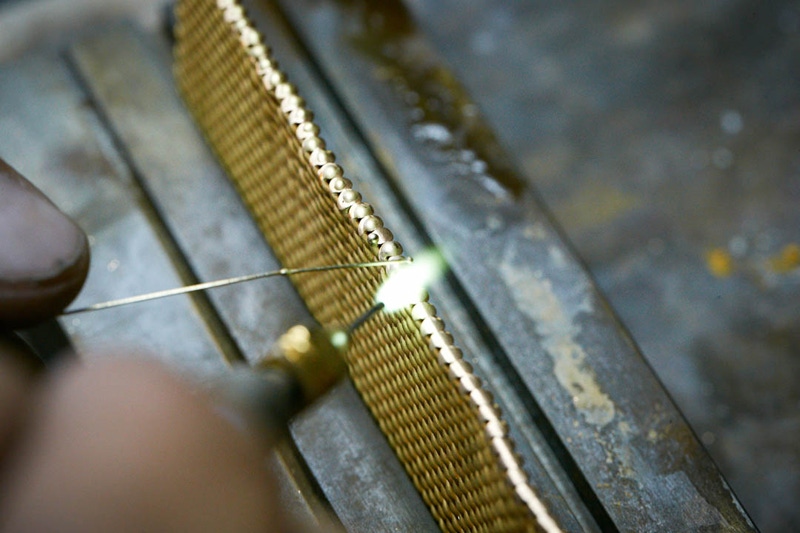

Arpels wore his watch every day from the moment of its creation to 1971, when, due to overwhelming demand, he reluctantly agreed to commercialise it for a few friends. In 2012, Van Cleef & Arpels launched a modern interpretation of this extraordinary, iconic timepiece. Offered in two sizes - 38mm and 42mm - the watches feature a dial in serene white lacquer. The central part of this dial has been adorned with a subtle honeycomb pattern, referencing the piqué bib of an evening shirt. The hours are represented by Roman numerals in accordance with the original watch, and the baton hands are ever present. Importantly, the case itself has received a beveling at the edge to enhance its ability to slide underneath a shirt cuff, as this was one of the key requisites set down by Arpels. One particularly rakish version of the Pierre Arpels timepiece is the 38mm white-gold model with a handmade gold Milanese-style bracelet. The bracelet is fabricated from coils of gold that are woven together, artfully compressed and then soldered together. The result is one of the most seductively stylish timepieces we've ever set our eyes on.

The point is, there are very few truly elegant men. Pierre Arpels was one of them and this watch is his legacy. Because, like Whitman, Pierre Arpels has also written his own poem, his own song of himself. But, with typical elegant understatement, he had encoded the poetry within the spare, economical, restrained, yet totally unforgettable lines of the Pierre Arpels watch.