Toupé or Not Toupé?

We examine whether the concept of hairloss will ever be completely disentangled from that of virility and masculinity, and look back on a few icons with surprising grooming routines.

“It’s only during the working day, which has gone into the night too frequently I’m afraid. [And] I’ve stuck it on for a few other pictures,” Sean Connery once noted with some displeasure. The tuxedo? Combat gear? Connery was, of course, referring to his toupé - that patch of faux hair that formed an essential part of the wardrobe department ever since his first credited movie, 1957’s ‘No Road Back’.

The title was somehow apt, this being before the Roonian Weave became convincing, back when only dubious science promised unlikely scalp action but hairiness was still widely considered a primary indicator of male virility. Connery had no concerns in that department from the neck down, but the top needed attention. Hence the fact that Mr. Bond wore a toupé in every one of his big screen romps.

That association between thatch and masculinity persists: studies have shown, for example, the deep reluctance of the US populace to elect a balding president. They’ve done it once, with Roosevelt, but otherwise hair has mattered - indeed, often the losers, from Nixon to Humphrey to McGovern, have been losers in the hair stakes too. Is this why Donald Trump went so far as to get a woman to give close inspection to his hair at a presidential race convention? Could it really be that his hair stylist is so incompetent as to make his real hair look like a toupé? “Hairpiece (Not a Hairpiece)?” as the David Letterman regular gag had it. It could soon be a state secret.

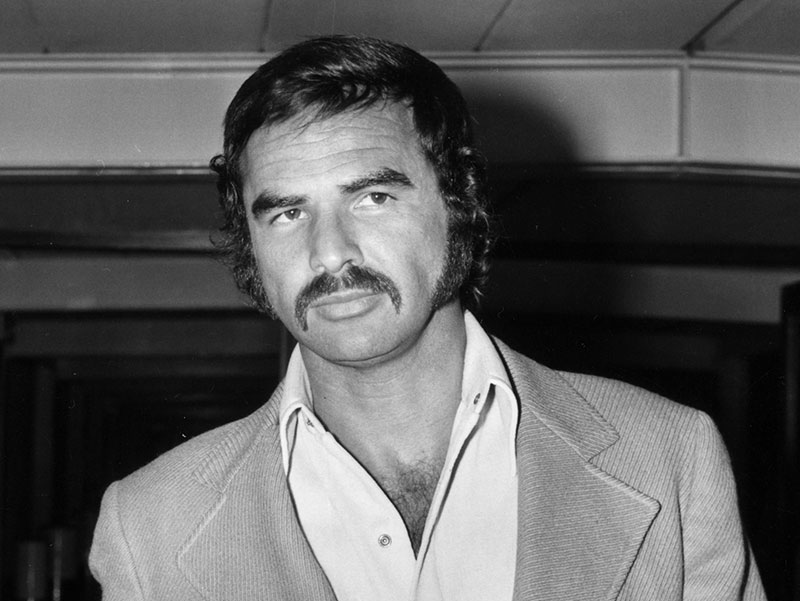

"Donald Trump went so far as to get a woman to give close inspection to his hair at a presidential race convention."Connery, of course, was not alone in gluing on a rug, even if he has been uncommonly open both about wearing one, and his dislike of doing so. Bing Crosby so hated wearing a toupé he started to select film roles on whether or not he could wear a hat throughout. Intriguingly, many other men who in their time were the embodiment of manliness wore a toupé too: Humphrey Bogart kept his secret, as did Errol Flynn, while Burt Reynolds was outed. Bankruptcy papers revealed unsettled accounts of $121,797 to Edward Katz Hair Design, which hints at how follicular fakery doesn’t come cheap. John Wayne wore one too, from the late 1940s onwards, as did Frank Sinatra. Both latter men spoke to the importance of a quality hairpiece, which today can push at four figures. When Wayne was challenged on why he wore a “phony toupé”, “it’s not phony,” he responded. “It’s real hair. Of course, it’s not mine, but it’s real.” Old Blue Eyes’ new brown mop, however, became increasingly unpersuasive as he got older, apparently because of an unwise switch to synthetic - available in any colour, but harder to blend in. Synthetics, of course, were not an option for earlier wearers of the toupé - French for ‘tuft of hair’, a soft, almost effeminate word compared with the gruff bluntness of ‘wig’, despite them being one and the same. Men would paint their heads in a bid to simulate hair. The ancient Egyptians wore palm leaf fibre wigs because, having shaved their heads to keep it free of pests, they found the result aesthetically displeasing. Julius Caesar added that laurel leaf to better disguise his wig’s apparent lack of conviction.

Certainly, men of power could shape heads of imitation hair - while, come the 16th century, the Puritans were railing against wig-wearing, the times also saw a resurgence among those more concerned with fashion. Louis XIV wore one to hide his baldness - he kept a staff of 40 wig makers at hand - and the court followed suit, until revolution saw the wig associated with aristocracy and gave rise to the very close cut of the guillotine. Since then about the only time the wearing of a hairpiece has become fashionable for men was when the Beatles’ mop tops sparked a craze among those young enough, ironically, to have plenty of hair.

As for those without such, is it such a bad thing to cover up with, as the 17th century pamphleteer Cotton Mather called them, these “horrid bushes of vanity”? Many other men - actors especially - have carried the well-covered demands of a role over into their private lives and - after ‘The Simpsons’’ take on Trump’s toupé-style do - donned the dog: John Travolta, Jeremy Piven and Nicolas Cage among them. Certainly, wig-wearing men may have been mocked since the time of Martial and Juvenal, but if today society continues to pressure women to be thin, still it pressures men to be thatched.

Then again, as the actor Billy Zane dismissively put it, is it just an undeniable fact that, at the end of the day, “a wig is a wig is a wig”, and frankly not worth the effort? After all, the tide, and the hairline, is perhaps receding. There is a growing gang of heroes, action and otherwise, who make up in muscle, smarts or sassiness what they lack up top: Bruce Willis, Vin Diesel, Jason Statham, Patrick Stewart and LL Cool J, not to mention the Dalai Lama. These are men who, really, look better without hair than they do with it.

Now that is a thought: in generations to come, when hair has finally lost its potency as a signifier of one’s machismo, and the shine from one’s pate will prove the real beacon of masculinity, perhaps we will be covering our hair up with bald caps, or taking special pills to make it all fall out. But don’t bet on it.