The Ballad of Justin and Twiggy

7 Minute Read

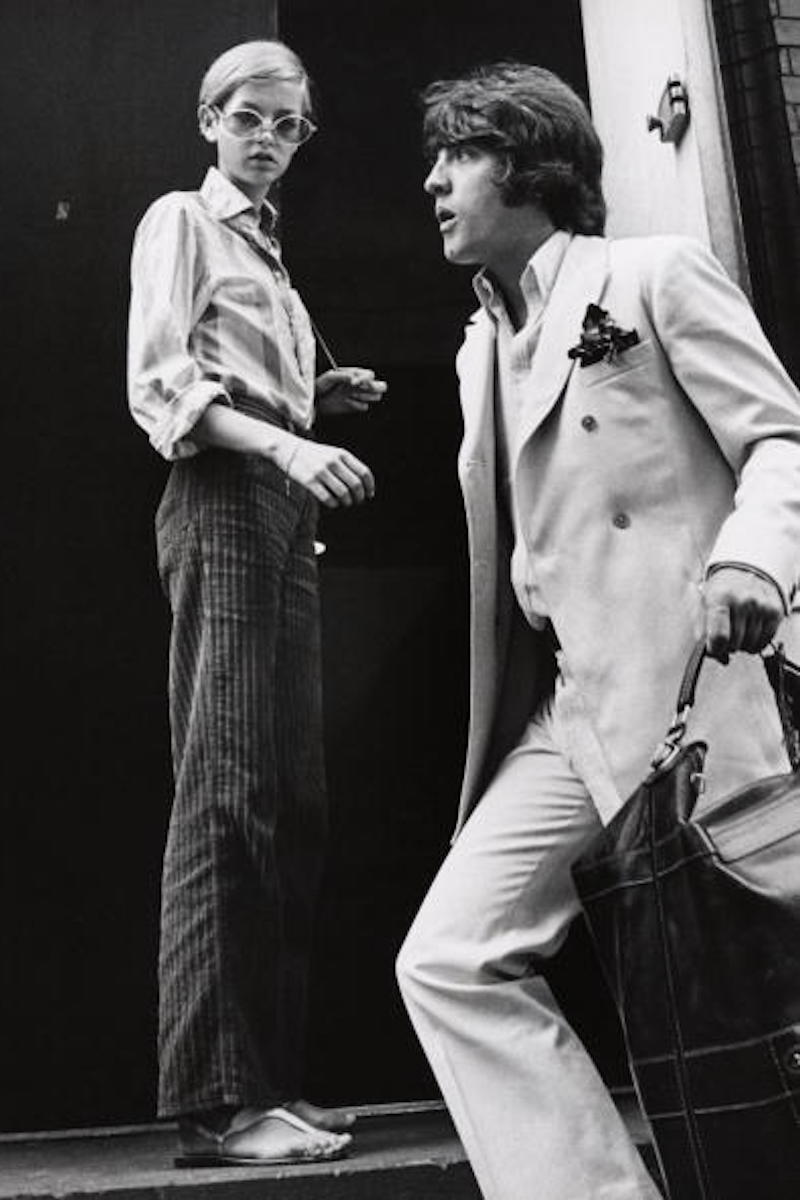

Great rake and sixties face Justin de Villeneuve recounts how he met, invented, loved and lost the world’s first supermodel, Twiggy.

“How would I describe myself?” ponders Justin de Villeneuve. He considers the question for some time, before breaking into a trademark grin that manages to express both delight and temerity. “I think ‘chancer’ just about covers it, doesn’t it?” Well, yes and no. It’s true that, de Villeneuve has done more than his fair share of ducking and diving, not to mention bobbing and weaving. But the word fails to capture the protean essence of a man who’s lived more lives than he’s had names. He’s been a boxer, a bodyguard, a bookmaker, a nudie-film salesman, an antique dealer, a hairdresser, a singer, an interior decorator, and most notably, a photographer.

‘Iconic’ is a wearily overused term today, but no other description seems fitting for the picture that de Villeneuve took for the cover of Pin Ups, David Bowie’s 1973 album. The bare-chested, pan-sticked, vermilion-haired Bowie stares the viewer down from his androgynous pomp, but it’s the mask-like face of the woman reclining on his shoulder that still catches de Villeneuve’s eye. He ‘discovered’ Twiggy in 1965 and spent the ensuing decade at her side, the Svengali-like figure who transformed a gawky Cockney teenager into the world’s first supermodel. “We were Twiggy and Justin,” he grins, “We came as a package. She deferred to me, and I devoted all my time and energy to her.” The percentage of de Villeneuve’s early fashion photography that stars Twiggy is a lasting testament to his devotion. “We were right at the centre of a scene, it’s true,” says de Villeneuve. “And I’d never taken a photo before and I didn’t know anything about or anyone in the fashion business. But, as far as success in any field goes, I’ve always believed that looking the part is just as, if not more important than being able to act the part.”

Born Nigel John Davies in Hackney, East London, to a bricklayer father and housewife mother, the future Justin de Villeneuve left school aged 15 and earned a living as a boxer under the name Tiger Davies (“my first soubriquet”). Having earned his stripes, the young Davies was employed by various East End villains as a bodyguard, auction barker, and all-purpose factotum, eventually ending up under the aegis of the Kray brothers. “Nothing dastardly,” he says, “just a bit of security here, a bit of merchandising there.” The most important lesson de Villeneuve took from Ron, Reg and their ilk was one of presentation. “The villains were the dressers then,” he says. “If you were a working-class Londoner, it was the villains’ look you aspired to.” Spending the lion’s share of his ill-gotten earnings in the mid-1950s on sharp garments from Soho boutiques, de Villeneuve says, “I didn’t have a home as such, but I always had my suits.”

His belief that appearances count for everything was confirmed when de Villeneuve catered Vidal Sassoon’s first wedding “with a load of dodgy wine that I’d knocked off, which tasted like paint stripper,” the posh labels that he’d affixed convincing grimacing guests that it really was charmingly presumptuous stuff. He also found himself hired as Vidal’s assistant. Still a teenager, he served as a dogsbody at Sassoon’s Bond Street premises under the moniker Christian St. Forget — “I thought you needed a poncy French name to work in hairdressing,” he says. It was at his friend Leonard’s salon, however, that de Villeneuve would encounter the woman who’d change his life.

“My brother worked there, and he was telling me about a 15-year-old from Neasden who’d come in as a Saturday girl, who wanted to be a model.” Of his first encounter with Leslie Hornby, de Villeneuve says, “She was wafer-thin, and she had this angelic face and swan-like neck, with this incongruous Cockney twang. I was bowled over.” To accentuate her angularity, de Villeneuve got Leonard to chop Hornby’s hair into a gamine crop. “When he’d finished, it was extraordinary,” he recalls. “Everyone in this big Mayfair salon saw her and went quiet. That’s when I knew we were onto something. Now, I thought, I have to get her photographed.” Leslie’s nickname came about as that task was being taken care of. “My brother called her Twiggy to wind her up, and when we got Barry Lategan to do her first set of pictures, he said, ‘That’s it, that has to be her name,’” de Villeneuve explains. By this time, he’d settled on his final nom de plume, too. “I’d been doing some interior decorating — something else I knew nothing about, but I’d seen inside a lot of nice houses, so I could talk the talk — and I needed a name to match,” he says. “I liked Justin, then someone suggested the name of a French town for a surname. I said, ‘What, like Harlow new town?’ And that was it — Villeneuve.”

The newly minted pair were poised to cut a swathe through pop culture. Seeing Lategan’s shots, The Daily Express declared Twiggy “The Face of ’66”. De Villeneuve immediately became Twiggy’s boyfriend (“I was 25 and she was 15, so it was a bit dodgy, but her parents accepted me, he says), and all-purpose fixer, tightly controlling the dissemination of her image — if only by default. “David Bailey, Terence Donovan and Brian Duffy all supposedly ‘banned’ Twigs from their studios because she had me as her manager instead of an agent,” he says. “My response was, OK, I’ll arrange the sessions, take the pictures and sell them to magazines as a package.” De Villeneuve had no formal training as a photographer, “But I’d seen Richard Avedon and Bert Stern in action — they had millions of assistants do the donkey work and set everything up, and all they had to do was walk down some stairs at the end and push a button. So I thought, how hard can it be?”

Avedon helped de Villeneuve set up a studio, and for the next eight years, he served not only as Twiggy’s ‘house photographer’ but — as her father once put it — “the rock on which she leans.” “It had to be serious money if anyone wanted to shoot Twigs,” says de Villeneuve, who also set up Twiggy Enterprises to market Twiggy dolls, clothes, and cosmetics. With his share of the proceeds, de Villeneuve lived very well indeed, ordering five suits at a time from Tommy Nutter, keeping a household staff (a butler, a valet, a chauffeur and an Italian chef), and getting through as many as 23 new cars in a year — ’60s classics from Rolls-Royce, Aston Martin, Lamborghini, Ferrari, and Maserati. The ride came to an end when Twiggy left de Villeneuve for actor Michael Witney, her co-star in the 1974 film, W. ‘Justin and Twigs’, the pair that once “came as a package,” haven’t spoken in decades. “It’s a real shame, because I don’t bear grudges, though I don’t lose any sleep over it. What does she blame me for? I don’t know. She always said I was a good gatekeeper, that I protected her from things like dope, which I’ve always hated.” He makes a helpless gesture. “Maybe she thinks I was extravagant, a wastrel. But that was the gig — easy come, easy go. The villains I knew were always carrying huge wads of notes around with them, buying everyone drinks, then a week later they’d be skint again.” He shrugs. “That’s how I was brought up.”

Asked whether he’s given any thought to his legacy, de Villeneuve grins. “At the end of the day, nobody cares, do they? I lived my life exactly the way I wanted, and I thoroughly enjoyed myself. Why not just say, he somehow managed to get away with it?”

This is an edited version of an article originally published in Issue 17 of The Rake.