THE CLIMBER: Lord Mountbatten

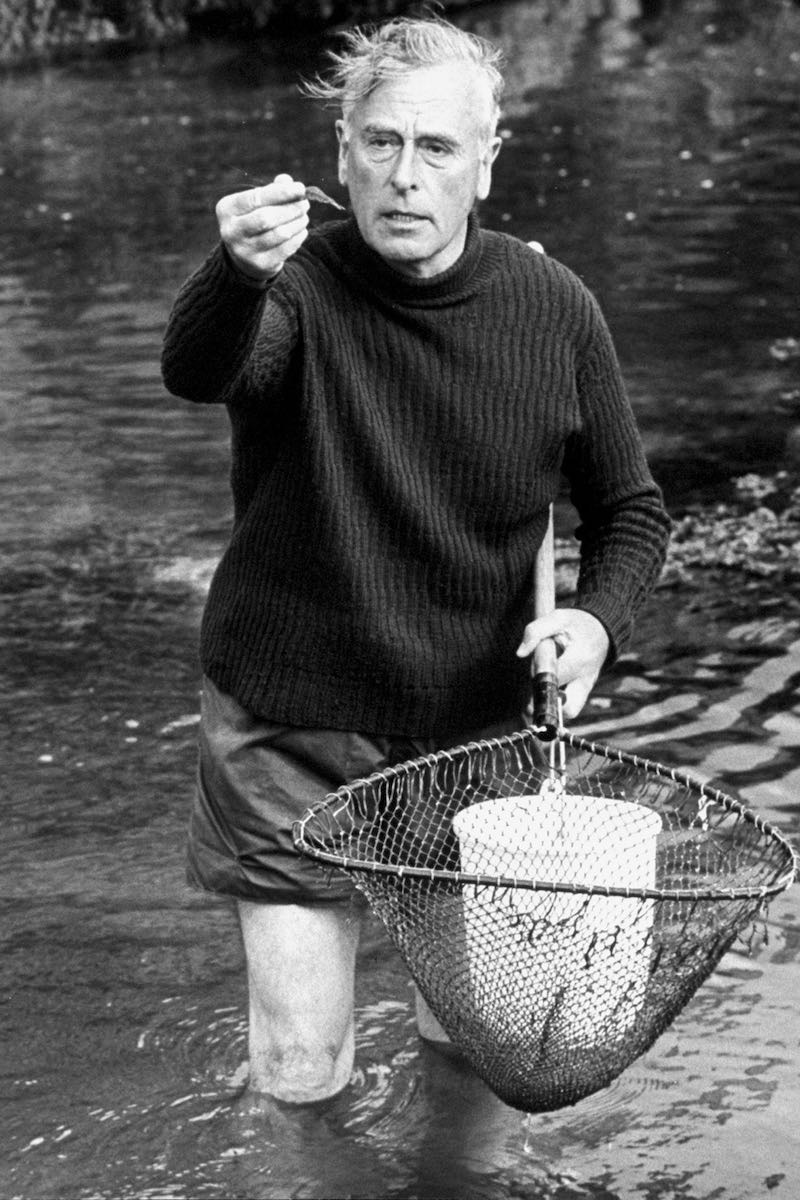

Originally published in Issue 42 of The Rake, James Medd writes that by the time of his death — a fishing boat; the Provisional I.R.A.; shock and outrage — Lord Louis Mountbatten had established himself as an English gentleman, a feted statesman, and, to some, one of the most heroic military men to represent the United Kingdom and its territories. But it wasn’t always so. With vaulting ambition sparked by familial shame, this royal foot soldier went in search of a higher purpose.

Louis Mountbatten has long been regarded as a quintessential English gentleman and hero, so it should come as no surprise to discover that he was, in fact, German. The fourth son of Louis of Battenberg and of Princess Victoria, granddaughter of Queen Victoria (still on the throne at his birth in 1900), he was one of a class of aristocrats who were not quite royal but were passed between the interlinked monarchies of Europe until a use could be found for them.

The same logic applied to the choice of his nickname. He was for some years known as Nicky, after his fifth name, Nicholas, until a visit by Czar Nicholas forced a switch, apparently at random, to Dickie. That this new moniker corresponded to none of the other names with which he was christened did not seem to bother him. The inconvenience of being at least half German, however, was to have a profound effect on his life and, indeed, on his considerable achievements. With the outbreak of the first world war, the British royal family found itself engaged in a battle with its cousins, but was loath to admit it. Consequently, all things Germanic fell quickly out of favour, and once fallen were swiftly swept under the nearest available carpet. For Louis’s father, this was serious: first a change of the family name to the rather less Teutonic Mountbatten, and then a humiliating order to step down from his exalted position as First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy.

No one took this setback worse than his son, the younger Louis, already well into a naval career that had started at 13 at the Royal Naval College, Osborne. To that point he had shown little promise, either as a thinker or leader, but shame was the spur. Determination to return his family to its former position became his driving ambition, and he undertook his purpose with endless reserves of energy and an undeniable ruthlessness.

So was born a cast-iron British hero: handsome, charming and glamorous, dedicated and brave, counsel to prime minister and monarch alike. Selflessness, however, was not one of his qualities; he gave his nation a great deal, both in war and peace, but it was not without counting the cost. He expected much in return, and enjoyed the praise, fame and even the medals in a rather un-British fashion. He was his own greatest admirer, and proudly so — indeed, he once admitted, “I am the most conceited man I have ever known”.

That said, if it was some advanced form of inferiority complex that drove him, perhaps we should all suffer such torment. Regardless of his motives, he achieved more in one lifetime than an entire fleet of other great men. His 79 years took in Machiavellian scheming, world-class philandering, war heroism, the fate of nations, and perhaps, it’s said, Barbara Cartland. Even his death, at the hands of the Provisional I.R.A. on a boating trip with his family in 1979, provoked such outrage that many believe it was a turning point on the path to peace in Northern Ireland. He was boastful, pushy, apt to name-drop, and, particularly in later years, something of a bore, but no matter — that was for the royal family or naval high command to suffer. To the ordinary British citizen and to many more around the world, this Germanic prince was the English hero incarnate, a born leader and a towering figure of the 20th century.

At first, his reputation was more predictably that of a playboy. Described as “quite crashingly handsome”, as a young naval officer he was friends with Winston Churchill and aide-de-camp to his cousin the Prince of Wales, later to become (briefly) Edward VIII. Sartorially he made his mark, too, fronting a vogue for ivory-coloured waistcoats and pioneering the wearing of the zip-fly on trousers. Life became only more glamorous when, in 1922, he married Edwina Ashley, the favourite granddaughter of the prodigiously wealthy banker Sir Ernest Cassell. She had taken the initiative of following young Mountbatten to India, where he had been assisting Edward on a tour that largely involved playing polo, and he put up little resistance to her suit. Their honeymoon was spent at her family home, Broadlands in Hampshire, later to become the family seat, but also in Europe and in the United States, where they visited Charlie Chaplin in Hollywood. Together they became the ‘Fabulous Mountbattens’, the very essence of high living in the interwar years, when the living was high indeed.

In truth, the marriage was a curious affair: Mountbatten himself once confided that, “Edwina and I spent all our married lives getting into other people’s beds”. Official biographies are discreet, but most other sources suggest that they were both bisexual, and Edwina was well known for the number of lovers — or ‘ginks’, as she called them — she managed to keep on the go at any one time. Their two children, Patricia and Pamela, even grew fond of their parents’ longer-term lovers, such as Mountbatten’s French paramour, Yola Letellier, on whom the novelist Colette based her Gigi.

That they made the most of their wealth and privilege can be seen in the fact that, despite the protection it afforded them, they almost fell to a scandal. In 1932, the gossip column of Sunday newspaper The People printed a story suggesting Lady Mountbatten had been caught “in compromising circumstances” with “a coloured man” and that she had been as good as told by the palace to move abroad until the fuss had died down. The Mountbattens were forced to sue, and won on a technicality, the court having identified the wrong “coloured man”, assuming it was the singer Paul Robeson when it was, in fact, the cabaret artiste Leslie ‘Hutch’ Hutchinson. (This famous bon viveur was one of Edwina’s longer-term lovers, her devotion to him such that she had famously bought him a jewelled penis sheath from Cartier.)

It was a lucky escape. Regardless, in between parties, Mountbatten had managed to sustain a naval career that, largely due to his charm, was proceeding satisfactorily. It was with the second world war, however, that he came into his own. At the outbreak of hostilities, he was captain in command of the destroyer H.M.S. Kelly, and quickly distinguished himself by leading a British convoy through fog in the evacuation of Namsos. After the ship was sunk in 1941 during the Crete campaign, it became the model for H.M.S. Torrin in the 1942 film In Which We Serve, a classic wartime drama directed by David Lean and Noël Coward; that the latter, a house-party pal, played the captain only helped embellish the Mountbatten legend at an early stage.

Even before this superior piece of propaganda was in cinemas, however, Mountbatten was back on dry land and taking charge, first as Chief of Combined Operations. His activities were by no means all successful, with commando raids in Norway and France producing high casualties to little effect, but here, as in peace time, his chief weapons of charm, determination and total self-conviction served him well. His desire to make his mark never left him, such that he even invented a new naval camouflage colour, Mountbatten Pink (disappointingly, a shade closer to a purple). By the end of the war he was Supreme Allied Commander for Southeast Asia, the man who accepted the surrender of the Japanese at Singapore and saw the recapturing of Burma.

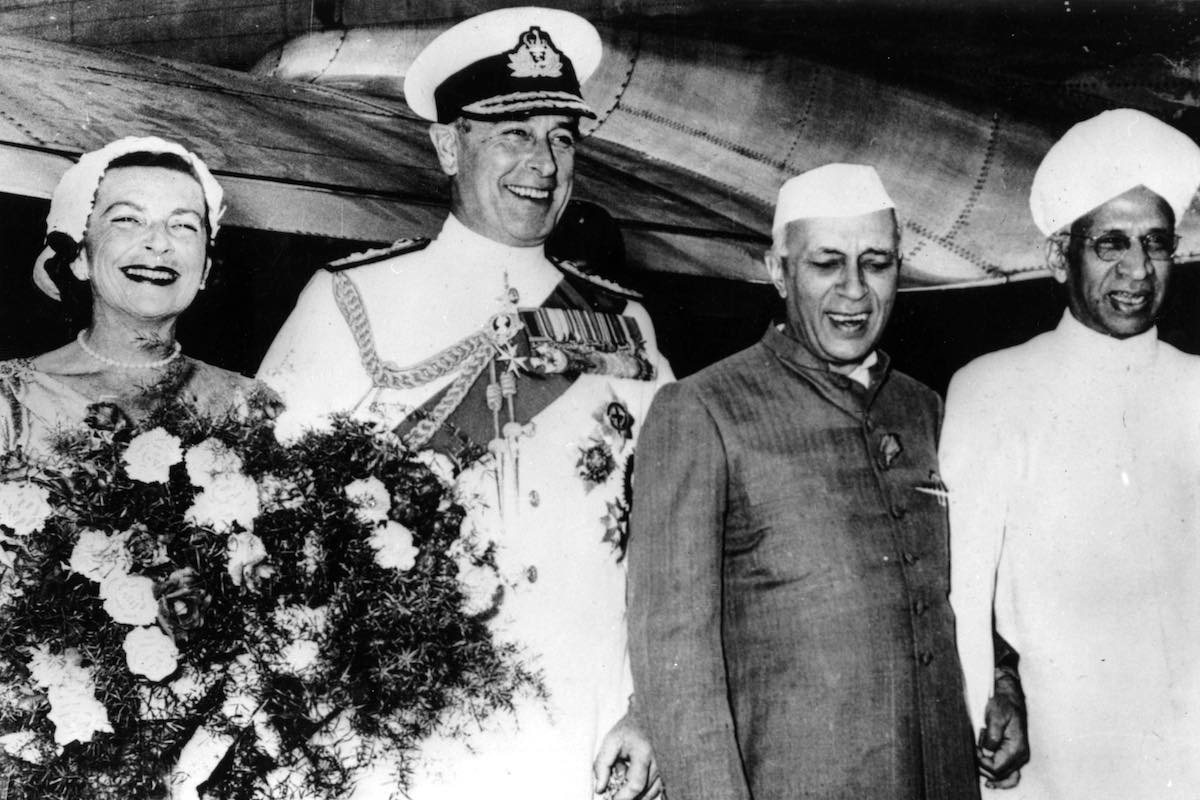

With peace came a still more strenuous role, as the last Viceroy of India. Given the task of easing the colony into independence, he was faced with the partition of one nation into two, with the birth of Pakistan. In this he was helped by Edwina, who was said to have seduced the Indian leader, Jawaharlal Nehru, perhaps under his guidance. He called her role ‘Operation Seduction’ and told one historian, rather slyly, that, “He and Edwina got on marvellously. That was a great help.”

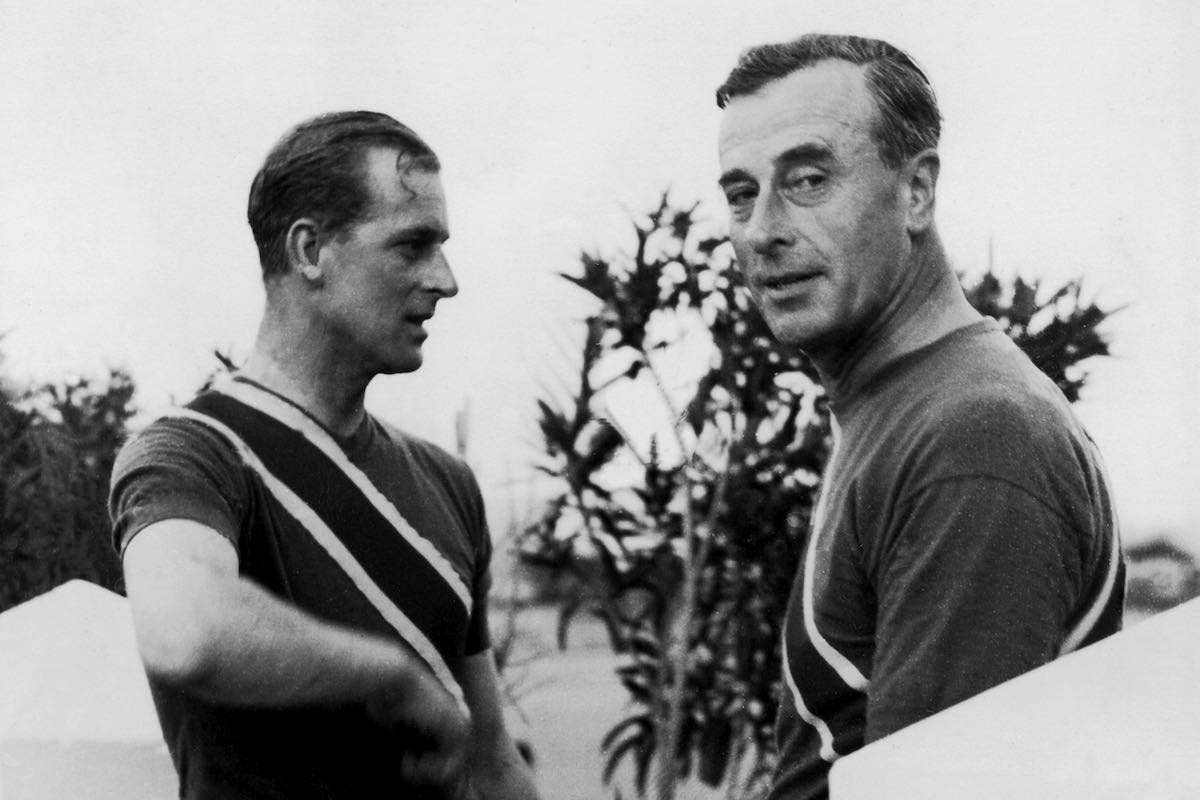

With the horrific bloodshed that ensued, no one could call the episode a success. It was, for Winston Churchill, “a melancholy and disastrous transaction”, and he broke off relations with Mountbatten for good at its conclusion. But that same year, 1947, was in other ways a triumphant one for Mountbatten, as he watched his nephew, Prince Philip of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksberg, married to Princess Elizabeth. This was the conclusion to a long and hard-fought campaign that had involved Philip, at his uncle’s insistence, writing regularly to the future queen when he was 18 and she just 13, and it set Mountbatten himself in an unassailable position at the shoulder of the British monarchy; indeed, it placed the name Mountbatten, which Philip had adopted at his uncle’s suggestion, at the heart of the monarchy. The close paternal relationship Dickie enjoyed with Philip was to carry on to Philip’s son Charles, who regarded Mountbatten very much as the grandfather he never had.

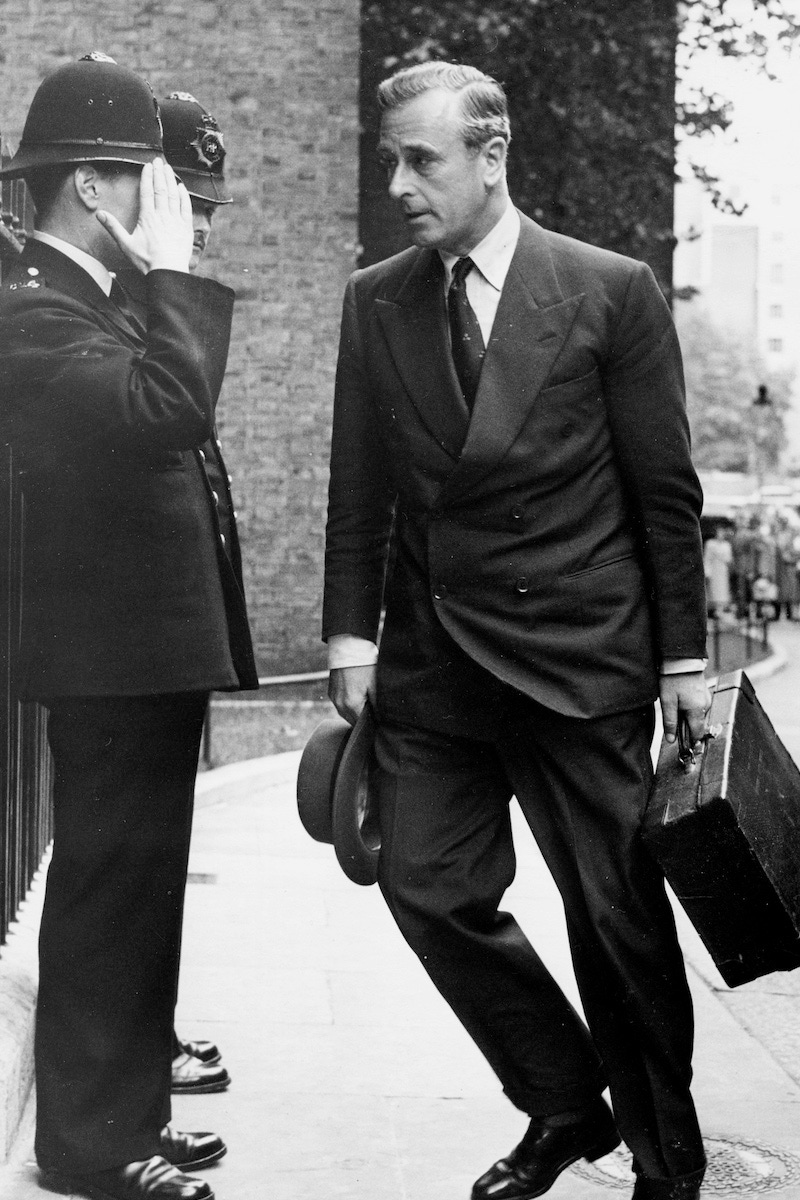

Many opposed the rise of the House of Mountbatten, but none, it seemed, could stop it, such was the force of its prime mover. Most gratifying of all, perhaps, was his elevation in 1954 to the position of First Sea Lord, the post his father had been forced to yield. From there he ascended to Chief of Defence Staff, from 1959 to 1965, helping to create the modern Ministry of Defence. He might, if certain stories are true, have gone further still. More than one source tells of a 1968 meeting between Mountbatten and press baron Cecil King, among others, in which it was mooted that Mountbatten become head of state after a coup against the then prime minister, Harold Wilson. Whatever the truth of it, that would surely have been too much even for the ambition of Mountbatten. No English gentleman, after all, could entertain treason, however German they might be.

This article was originally published in Issue 42 of The Rake.