THE KEEPER OF GREATNESS: Bao Dai

Bao Dai was the 13th and final emperor of Vietnam. He didn’t inspire devotion or much confidence: the American satirist S.J. Perelman, for example, described him as a ‘slippery-looking customer, rather on the pudgy side, and freshly dipped in Crisco’. But, Stuart Husband writes in Issue 58 of The Rake, a legacy can take time to be realised…

In 2017, Phillips auctioneers announced that it had set a new world record for the highest price achieved at auction for a Rolex wristwatch. Naturally, the timepiece it sold — for $5,060,427, and after an eight-minute bidding war between 10 enthusiasts at the Hotel La Réserve in Geneva — was extraordinary even by the standards of the storied Swiss watchmaker. It was a Reference 6062, a triple calendar with moonphase indication, crafted in 18-carat yellow-gold, and is one of only three black-dial models known to exist. Furthermore, it was the only one featuring diamond markers at the even hours, making it a unique piece. One other fact elevated it to holy grail status for horologists: it was known as the Bao Dai Rolex.

There can be few provenances more prestigious than having once adorned the wrist of a bona-fide emperor — albeit the last of his line — whose honorific, granted to him when he ascended the throne of Vietnam in 1925, aged 12, means ‘Keeper of Greatness’. Bao Dai acquired his statement wristwear in the spring of 1954, in Geneva. Following the Indochina war, the world powers were meeting at the Hotel des Bergues to negotiate with the Viet Minh on the future of Vietnam. During a recess, and presumably in need of distraction, he stepped across the street to Chronometrie Philippe Beguin, a famed Rolex retailer. The emperor’s request to the staff was as stark as it was imperious: he wanted the rarest and most precious Rolex ever made. Many glittering examples were presented to him; all were rejected. Finally, an emissary was dispatched from the company’s workshops on the city’s outskirts, bearing the 6062 in a strongbox. Bao Dai was assuaged.

That the emperor seemed to be more interested in bling while his country’s future hung in the balance — the peace accord between the French and the Communists split the country into North and South, and Bao Dai was deposed a year later — came as no surprise to a large proportion of his countrymen, who viewed him, at best, as a stooge — of the French colonialists, the Japanese occupiers of World War II, Ho Chi Minh’s Communists, and, finally, the French again — and, at worst, a playboy and adventurer. He was certainly no slouch when it came to hunting expeditions in the Vietnamese rainforest, where he was believed to have singlehandedly bagged a large percentage of his country’s tigers (he liked to track them into their dens, with a lamp on his head and his rifle at his side). But he also championed reforms in the judicial and education systems, and dispensed with the more outré trappings of Vietnamese royalty, not least the ancient Mandarin custom that once required aides to touch their foreheads to the ground when having the temerity to address the emperor.

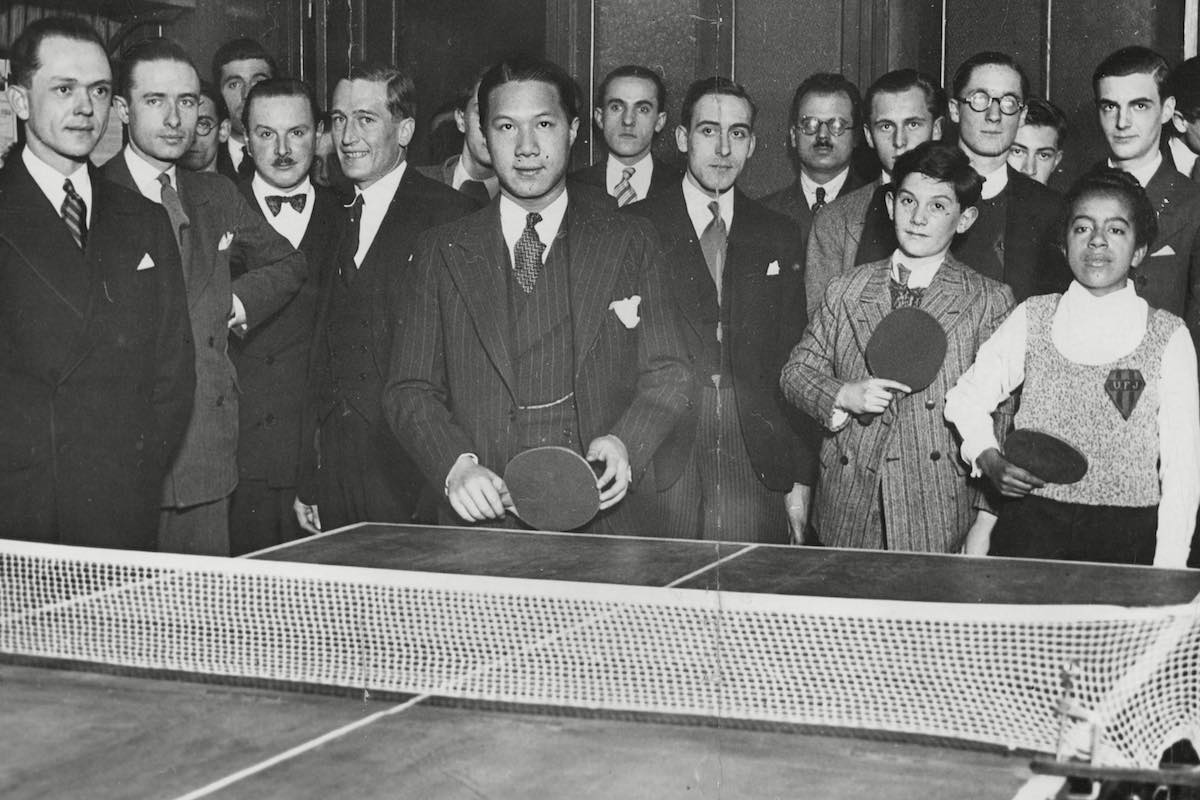

Those customs, and the Vietnamese Nguyen dynasty, had endured for a century and a half by the time Prince Nguyen Vinh Thuy ascended the throne as the 13th (unlucky for some, and particularly for him) Emperor, Bao Dai (pronounced bah-oh dye). But it wasn’t his fate to inspire devotion, or even much confidence. “A slippery-looking customer, rather on the pudgy side, and freshly dipped in Crisco,” was the caustic verdict of the American satirist S.J. Perelman, who ran into the emperor in 1947 in one of the more exclusive nightclubs of Tsim Sha Tsui, where he was habitually entertained by a protective phalanx of hostesses (a drawing by cartoonist Al Hirschfeld, who was travelling with Perelman, shows a toad-like, besuited emperor, with slicked-back hair and sideburns, accepting a light from one of those hostesses while crooking his arm around another, regally haughty in a thigh-slit gown). Even his legitimacy was suspect: his father, Emperor Khai Dinh, was widely assumed to be homosexual, or impotent, or most probably both. One theory posits that Bao Dai was the son of the emperor’s aunt, and that his father was a senior French colonial court official.

Whatever the truth, expediency would be Bao Dai’s default setting, which was nothing short of pragmatic, as his reign coincided with a tumultuous geopolitical age when his country became a testbed for some of the 20th century’s most bellicose -isms. He was born in 1913, within the walls of Hue’s majestic Imperial Palace, on the banks of the Perfume River. He was widely seen as the ‘pet’ of his French overlords (who had made Vietnam a protectorate in 1858) to counter rumblings of nationalism and anti-colonialism in French Indochina. Sovereign in little more than title, he was sent to Paris to complete his education, where he developed a taste for all the finer things the west had to offer: tennis, Savile Row tailoring and bespoke footwear (he favoured natty correspondent shoes for hunting), and fast cars, most notably a famed Ferrari 375 MM Spyder re-bodied by Scaglietti to a blue/silver Tour de France.

When the French hauled him back to Vietnam in the early 1930s, Bao Dai submitted to the parades staged in his honour (the adoring crowds a marked contrast to the peasant uprising the French had just violently quashed), but his youthful political idealism was quickly stifled, and he effectively retreated to his hunting lodge (a.k.a. Palace III) in Da Lat, a striking Art Deco building that resembles nothing as much as a vintage factory on a London ring road. “During his holidays in the palace, there were always a regiment of imperial guards, a train of cars called ‘Cong xa biet dien’, and private airplanes to serve him and his family,” offers a contemporary guide to what is now a stop-off on the tourist trail (Bao Dai had married Marie-Therese Nguyen Huu Thi Lan, dubbed the ‘Imperial Princess’, in a lavish ceremony at the Imperial Palace in 1934; they went on to have five children). Surprisingly for such a voracious hunter, the trophy count within is low — just three tiger skins and an elephant tusk. There’s also little of the gold-tap ostentation beloved of kleptocratic sovereigns, with the building’s most singular flourish being a tower called Vong Nguyet (“waiting for the moon”), where the emperor could observe the peregrinations of that heavenly body.

By 1945, however, earthbound matters were more pressing. When the Japanese swept across south-east Asia during World War II, Bao Dai was allowed to retain his throne in the hope that his presence would demonstrate continuity and quiet the population; with defeat looming at the end of the war, the Japanese staged a coup, interning all French officials and eventually tracking down the emperor (who was on yet another tiger-hunting trip), exhorting him to declare Vietnam an independent state. Bao Dai thought he’d achieved by accident what nationalist and communist groups had been fighting to achieve for decades, and he ordered his prime minister, Tran Trong Kim, to set about tearing down French monuments and preparing for a heroic independent era. However, Ho Chi Minh’s Communists had other ideas, launching the August revolution and proclaiming their own Democratic Republic of Vietnam at the Japanese surrender. Bao Dai agreed to step down at the request of Ho in return for a post as his ‘special adviser’ (a power-sharing deal the Communists had no intention of honouring), abdicating the throne in a formal ceremony at the Imperial Palace, and reportedly declaring, “I would rather be a simple citizen of an independent country than the king of a dominated nation”, before being neither, as he was summarily dispatched to exile in Hong Kong and China.

That should have been that: the last emperor, now plain Mr. Vinh Thuy, living out his twilight years in the standard-issue clubs, casinos and riviera fleshpots. But in 1949 he was coaxed home by the French, who were lining him up as a possible alternative to Uncle Ho, whose guerrillas were locked in combat with the French colonial army. Bao Dai was furnished with the title of Premier and re-established as emperor, and, though his government was recognised by the U.S. and Britain in 1950, it never won widespread popular support, perhaps owing to Bao’s long-entrenched habit of leaving major decisions to his advisers while he holed up with his mistresses in the pipe-tree-shaded precincts of Palace III (his official stipend from the French at this time was more than $4 million a year, leaving plenty of small change for prestige accessories). Following Vietnam’s division after the ‘Rolex summit’ of 1954, Bao Dai tried to assume power in South Vietnam, but was thwarted by the American-backed Premier, Ngo Dinh Diem, who organised a referendum in 1955 that deposed Bao Dai and drew a definitive line under the Vietnamese monarchy.

The Last Emperor had four decades of Parisian exile ahead of him. He died in 1997, and was interred in Paris’s Cimetière de Passy. He remained largely silent as the Americans entered the fray in his homeland, apart from issuing the occasional bromide, such as, “The time has come to put an end to the fratricidal war and to recover at last peace and accord”. Having squandered most of his royal fortune, he spent the final years of his life in a modest Paris apartment. However, he hung on to his Rolex. Despite some observers feeling that Vietnam might not have embraced communism, and avoided war with America, if Bao Dai had played his cards differently, he finally seemed under no illusions about his failures and limitations. According to one historian, the emperor’s inner circle included a “spectacular blonde French courtesan” billed as a member of the ‘Imperial Film Unit’. Once, on hearing her disparaged, Vietnam’s ultimate ‘Keeper of Greatness’ remarked: “She’s only plying her trade — I’m the real whore.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 58 of The Rake.