Unbuttoning the History of the Shirt

How a modest undergarment became the most elegant, versatile and fundamental of men’s wardrobe staples – and an ensemble’s focal point in its own right.

“They’re so functional as well as beautiful,” says Jermyn Street shirt-maker Emma Willis of the male shirt – a garment which is not just her passion in life, but also her vocational calling. “Everything about it – the mechanics that give it maximum flexibility without too much volume and so on – appeals enormously. It’s such a wholesome product in terms of purity of materials.” Needless to say, The Rake heartily agrees.

The word ‘shirt’ has become a catch-all one, referring to a variety of upper body garments - from slim-fit pieces in Swiss poplin and organic pique with cutaway collars at the top of the scale, to nylon atrocities worn by Stella-bloated football fans who can only iron them properly with the aid of a wok at the bottom. But a ‘shirt’ in gentleman’s parlance – as in what some Americans separate from the chaff by calling it a “dress shirt” – is the ultimate staple garment for men of all backgrounds and inclinations. (Even dot-com hippies, Trustafarians and student dweebs who brag about not owning a suit almost certainly possess at least one garment with collars, sleeves, cuffs and a vertical fastenable opening.)

While most sartorial historians would trace the history of the shirt back to a linen garment from 3000 BC found in 1913 in a First Dynasty Egyptian tomb at Tarkan, they are unable to come up with a universally accepted, linear narrative from there to here. Plenty of unequivocal facts about the modern shirt’s lineage, however, do exist. Fourth Century night gowns and under garments should be counted as ancestors, as should 12th century finery in linen and silk and 16th century, lavishly embroidered, puffy garments topped with frilly, lace ruffs.

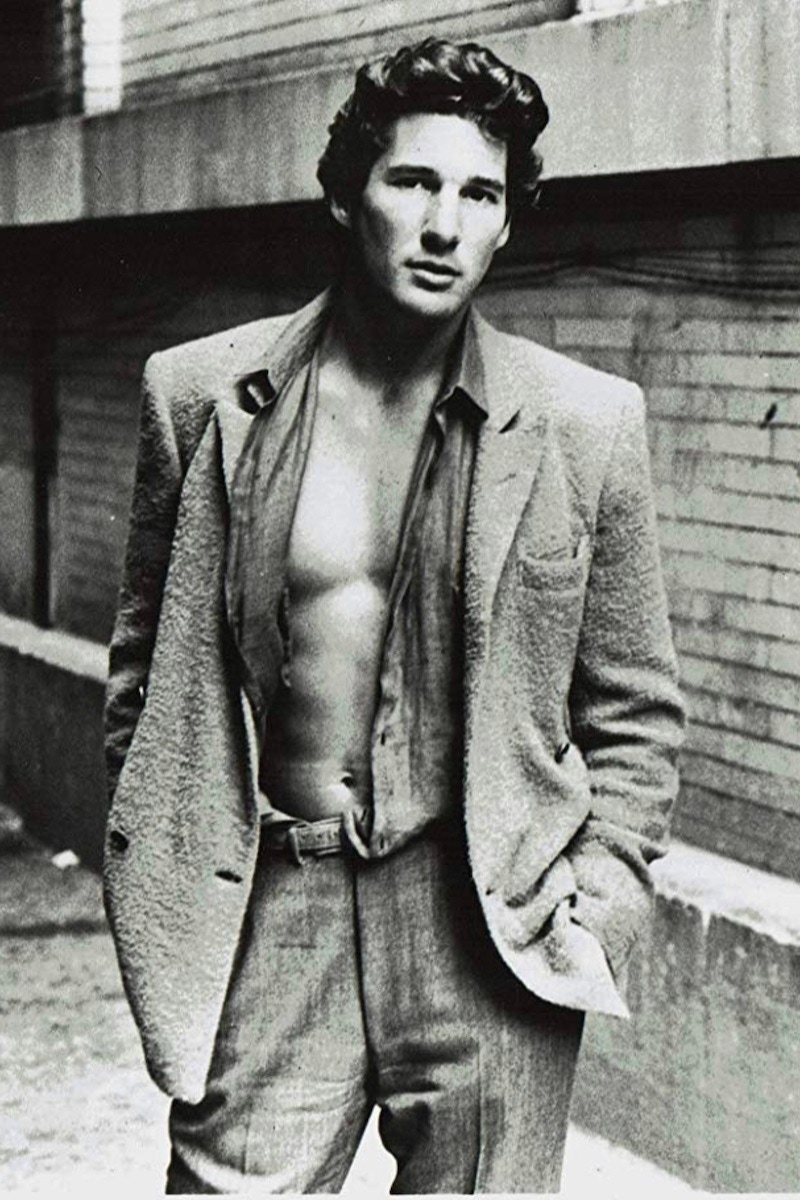

We also know that, for centuries, the bulk of a man’s shirt would nearly always be hidden under his outerwear - exceptions being lowly figures such as shepherds in medieval artworks, or bar-room carousers such as Tom Rakewell in Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress, gloriously drunk and surrounded by a flurry of prostitutes.

For some analysts, the narrative of the shirt as we know it today really begins in the 1700s, when men grew tired of closing wrist-slits with pieces of string and started insisting on boutons de manchette to fasten the cuffs of their blousy torso-wear. These were initially simple coloured glass buttons but inevitably, embellishment - diamonds, worked gold, miniature painted scenes – before long began appearing on men’s wrists.

A year after the first documented use of the word ‘cufflink’, in 1789, came the French Revolution, and Robespierre’s followers deciding to reject the bourgeois finery of Versailles and instead wear courser white linen shirts, often with cravats, prompting the major romantic poets across La Manche – Byron, Keats, Shelley – to enhance their rebel credentials by adopting the guise (which makes students wearing Che Guevara T-shirts in a spirit of faux-revolutionary zeal seem even more woefully undignified than before, does it not?)

About here on the shirt’s narrative arc arrives the lead protagonist, George Bryan “Beau” Brummell, who turned the linen, tunic-shaped undershirt and muslin cravat into staple garments for de rigueur men of the time and, in introducing the then expensive notion of laundering linen rather than dousing it with perfume, gave rise to the idea of detachable collars and cuffs – the promontory sections of the garment wearing quicker and requiring more regular washing than the rest – and thus the shirt was suddenly affordable for a far greater portion of male society.

It was practicality, too, that led to the shirt’s anatomy being tweaked further and further until, at the end of World War I, the modern shirt - with fixed collar and buttons all along the front – was popularised. All of which leads us to the glorious litany of charming choice that is men’s shirting today. Contemporary men are, to put it mildly, spoilt: Savile, albany or button-down collars; squared, rounded, cocktail or mitred cuffs; as many button choices as there are luminous bodies in the cosmos; numerous cotton weights; custom embroidery, contrast stitching or monograms… A modern shirting emporium is, to the informed dandy, an Arcadian fulcrum of abundance: a place where “the agony of choice” is a baffling oxymoron.

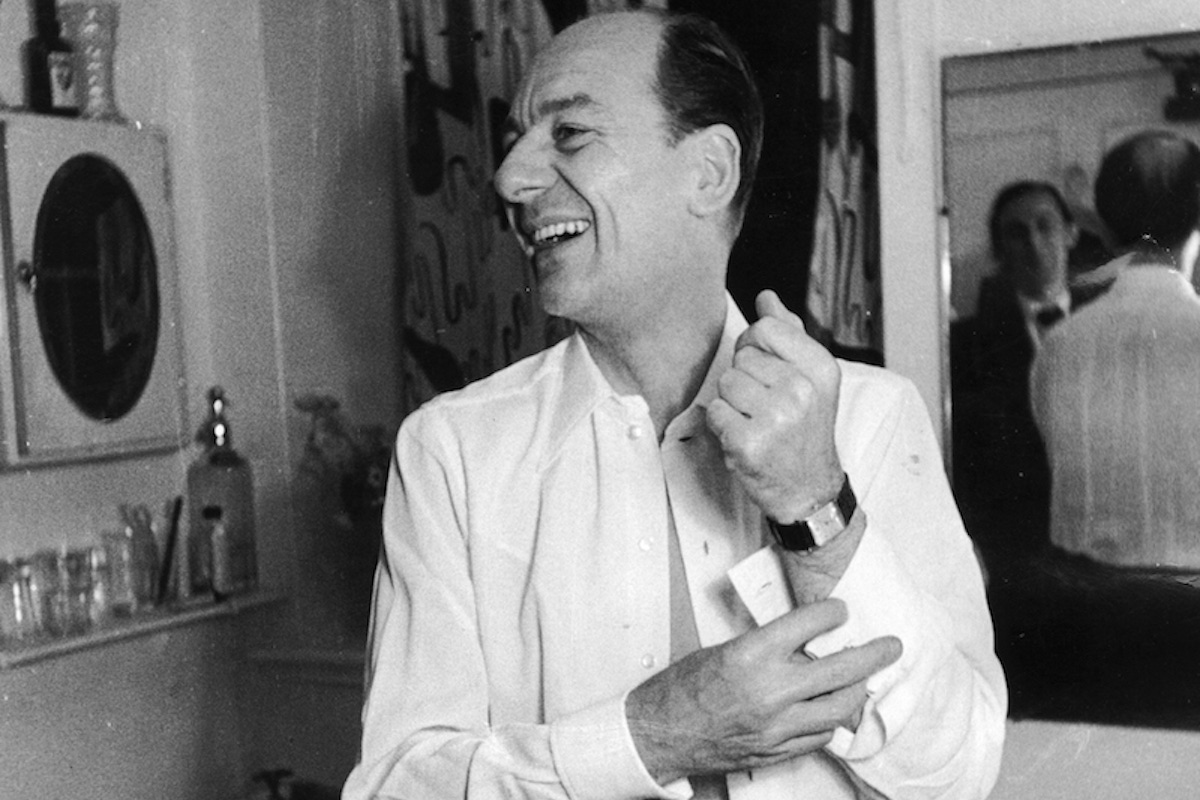

Were one to enter the fabled doors of 71-72 Jermyn Street, a store with such a staggering selection of fine shirts, this ‘oxymoron’ would become a very real issue. Home to Turnbull & Asser, this prestigious heritage brand has welcomed over the years such style luminaries as Sir Winston Churchill, Sean Connery and Prince Charles, all of whom valued the incredible quality and transformative effect of the brand’s shirts. Whilst the shirt has endured popularity throughout the decades, for Turnbull & Asser, this humble garment has never been more relevant. Steven Quin, T&A’s retail director and Royal Warrant holder since 1999, once told The Rake, “the shirt is now such an important part of the modern man’s wardrobe, as the need to wear a jacket becomes less and less. With men looking after their bodies more, it’s important to have a good fitting shirt that’s not too blousy and reflects the work they put in at the gym. Our bespoke service gives the customer the opportunity to make a shirt that’s individually tailored to their body and to fit them exactly as they wish, whilst allowing them to stamp their own personal style on the shirt with an infinite selection of collar and cuff styles on offer. A Turnbull & Asser bespoke shirt is like no other, made at our factory in Gloucester by the most skilled machinist and crafts people using the best quality fabrics available. To slip on a crisp cotton bespoke shirt made specifically for you is the most enjoyable feeling and gets you confident and ready for the day ahead”.

For Emma Willis, a catholic selection is the core of a modern man’s sartorial arsenal – and isn’t short of advice for men starting out. “A collection of beautifully cut shirts in fine, breathable cottons for work, smart casual, linens for holidays and brushed cottons for winter will be pleasurable to wear and well worth investing in,” she says. “Swiss or Italian cottons, woven with the fine, smooth and strong yarn from Egyptian Giza 45 raw cotton will not shrink or fade and will last for many years, becoming softer with every wash but not smaller. Like great quality shoes, jeans or tailoring, you wear your favourite shirts for years – until they fray – and your favourite white shirt should be the most flexible piece of clothing you own.”