Worn To Be Wild

The history of the biker jacket packs plenty of Tarmac-shredding rebellion – but plenty of sartorial nuance, too.

“I don’t have one,” says David Himel, with a hint of regret. “I almost had one. And unless there’s some miracle I’m never likely to own one – getting an affordable one now isn’t going to happen.” Himel’s lament is for the motorcycle jacket by Peters, a long-closed west coast American manufacturer. In a heartbeat, though, he is reminded of a rival for his affections. “A jacket by Leathertogs of Massachusetts was possibly the most spectacularly beautiful motorcycle jacket I’ve ever seen. But you don’t see its like often now. It’s extremely rare.”

Himel is one of the world’s foremost collectors of motorcycle jackets, and his passion for the style led the erstwhile vintage clothing dealer to launch, in 2006, his own line of pre-second world war-inspired jackets. Since then, Himel Brothers has become the go-to name for authentic detailing and construction techniques in what is the most ice-cold mutha of a garment in the male wardrobe.

“The appeal of the motorcycle jacket goes beyond riding a motorcycle,” Himel says, as though the wheels of steel – with their intonations of rebellion and the outlaw lifestyle with which society has imbued them – have little to do with it. “The fact is, people always want to look cool, they want to look tough. But beyond that, the motorcycle jacket is also one they want to live with and through, to put their mark on, to see it change and age as denim does, and then maybe to pass it down.”

That was how Himel was introduced to his – a fellow punk offering him his highly personalised black jacket. It gave him the look he wanted, of course, and it provided a useful layer of protection (less for falling off a bike as for fending off flying bottles during bar brawls). But there was something deeper going on. “Wearing leather is primeval,” he says. “Leather was the first thing humankind wore.”

Perhaps that is what lies at the root of the motorcycle jacket’s appeal: the undertones of the material – hardy, womb-like and ageing gracefully, much like the skin we live in – and the overtones of 20th century pop culture, albeit an unholy blend of Hells Angels, rock ’n’ roll, and the near-pastiche of The Village People and George Michael on the cover of his 1987 album, Faith.

Latterly, the motorcycle jacket, somewhat against the type of its hundred-year history, has been recast as a piece to be worn over formalwear, as though today’s CEO might underline his psychological powerplay by giving the impression he’s arrived at the board meeting by Norton. A few year ago, Tom Ford even created biker jackets for toddlers, which seemed to suggest that the style is so macho it can’t help but have a camp side straight out of the dressing-up box.

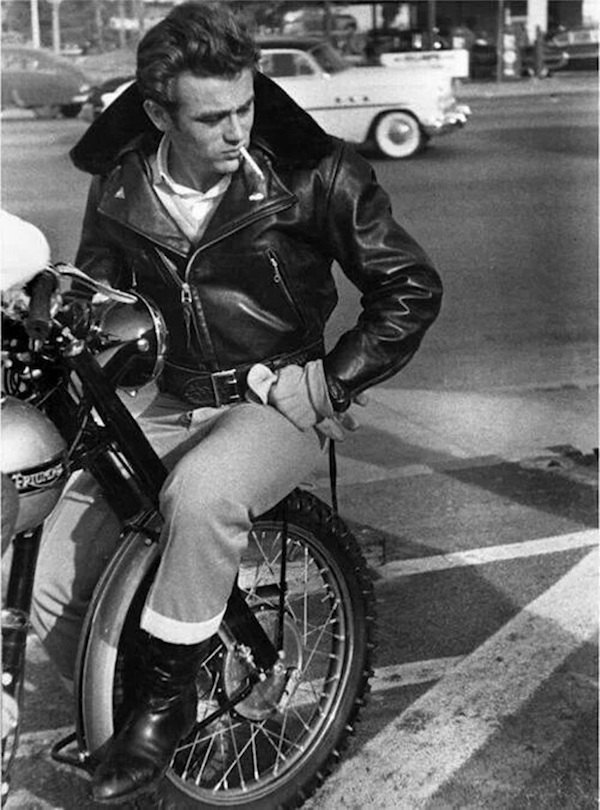

The iconic biker look came along after the second world war, when it incorporated practical rolled jeans, heavy, buckled biker/engineer boots, T-shirts and denim jackets – rugged, working-class clothes that distinguished their wearers from the ‘men in grey suits’ of conservative middle America. The leather biker jacket defined the look, and the connotations of black leather – of fetishism and fascism – only added to the biker’s outsider status.

Many wearers were genuinely tough, or at least were perceived as tough by a hysterical mainstream. Some bikers in the United States played on that perception by wearing a patch on their jackets proclaiming themselves a ‘1%er’. The badge referred to the Fourth of July weekend of 1947, when a 4,000-strong motorcycle rally descended on the small town of Hollister in California. The press sensationalised the ensuing disruption as the ‘Hollister riot’. Approached for comment, the American Motorcycle Association allegedly responded by saying that 99 percent of all motorcyclists were law abiding. The implication? That the remaining one per cent were outlaws.

Almost inevitably, numerous bikers – many of them GIs returning from the war, keen to regain a sense of comradeship, and some perhaps drawn to the adrenalin – allied themselves to the one percenters. And, as they did, the motorcycle jacket came to signal danger to those in mainstream society.

Popular culture perpetuated the idea of bike-jacket wearers as untrustworthy and antisocial, notably with the 1953 movie The Wild One, in which Marlon Brando played the disaffected leader of a biker gang (“What are you rebelling against, Johnny?” he’s asked. “What have you got?” comes the reply) and with a spate of biker movies that followed, including Cycle Savages and Easy Rider (both 1969). In Britain, rockers and then greasers were seen, mistakenly, as the grubby ne’er-do-wells battling scootering Mods who wore their hair neatly parted and army surplus parkas over their foreign suits.

Indeed, the media arguably made the motorcycle jacket. In the days before mass entertainment, it was more a tool than talisman of terror. The origin of the motorcycle jacket dates back to the birth of the motorcycle at the end of the 19th century, when the first riders took their equipment largely from the military equestrian tradition – puttees, cavalry boots and gloves, and a leather tunic from which a more specialised garment would develop, as with pioneering aviators and car drivers.

North America, especially, was awash with jacket makers in the '20s, '30s and '40s – Hercules, Joseph Buegeleisen Co, Indian Motocycles (with its Ranger style), Rangerette (for women), and Harley Davidson (with its Cycle Champ and Cycle Queen) – who supplied local needs and responded to local materials. On the west coast of the US, for example, wool was in greater supply, so played its part in the styles made; on the east coast, rubber manufacturers typically turned their hand to shoemaking, and, since this got them working with leather, ended up making jackets as a sideline. The motorcycle jacket as it is perceived now is the result of many tweaks and evolutionary steps. What gives it such a boldly graphic look is that it was created not in one season, responding to fashion’s momentary fancy, but over generations, for practical necessity.

“The early jackets belonged to an era when people used to hand-draft patterns,” Himel explains. “There was a lot of intuitive adaptation, cutting the pattern on the body. There was no specific, standard way to design a motorcycle jacket – it had to fit, you had to be able to move in it, and it had to last, since then, typically, a jacket might cost several weeks’ wages. Most makers copied each other but made theirs just that little bit better than the one by the guy down the road, while taking into the design ideas that the customer had too. Before mass manufacturing came in, when price and brand became more important than quality or design, the maker could innovate on the spot.”

So the design of the motorcycle jacket improved in increments to form a garment that was, above all, fit for purpose. One Himel Brothers style, the Score, based on a jacket design of the now-defunct Score Sportswear of Toronto, zips up only to one side, leaving a clean, aerodynamic front that won’t catch in engine parts. “But back then, motorcycle jackets weren’t designed to be worn open to look cool in a bar,” Himel says. “Motorcycle riders wanted to look like superheroes, for sure, but first they wanted a jacket that worked.” Testing was no less rudimentary: one company, the British Motorcycle Co, of Montreal, ensured the toughness of its jackets by fitting them to a mannequin and dragging the mannequin behind a truck. That story speaks to the fundamental spirit of the motorcycle jacket – that it is anything but prissy.

As cinema reinforced the press’s overblown portrayal of the one percenters, the notion of bikers as 20th-century cowboys, always on the wrong side of the sheriff, was sealed in a form of American anti-hero myth-making – so much so that some high schools barred their students from wearing bike jackets. Note the joke in the movie Back to the Future II (1989), when Marty travels in time to 1955 and, asked to dress so as to be less conspicuous, buys a Perfecto jacket.It is the Schott Perfecto that arguably came to define motorcycle-jacket style. It is the one that Johnny Ramone insisted his band members wore, and it is the one adopted by 1980s boy band Bros. Irving Schott, the company’s founder, had been a coat maker for 15 years – he is believed to be the first to put a zip on a casual jacket – when Beck Industries, a Harley Davidson distributor, came calling. It wanted Schott to devise a distinctive style of jacket to protect Beck’s customers on their rides. For $5.50 RRP apiece, it got it.

Many of the details would become characteristic of the genre: a belted front, zip-up sleeve-cuffs, hidden collar snaps, several pockets (a D-pocket, change pocket and a side pocket, strategically positioned to make access easier during riding), and epaulettes with studs. The tweaked 618 model came in the 1940s, made slimmer and replacing the D-pocket with two side pockets and an angled breast pocket. This is the one that Brando wears – the one that scares grandma.

“Brando clearly helped the motorcycle jacket’s image, even if punk probably has more resonance for it today,” says Jason Schott, Irving’s great grandson and now Schott’s chief operating officer. “It’s really hard even for me to pin down quite what the nature of the jacket’s appeal is, but it’s such a strong statement and seems to have transformative powers. People who don’t think they can carry off a motorcycle jacket put it on and they become a badass. Even my five-year-old daughter once saw a man standing by the side of the road in one, and announced that he was a ‘bad guy’. The Perfecto was an innovative design when it came out, but it resonates because it’s been picked up by generation after generation of badasses to become the badass uniform.”

Well, badass in the US, perhaps, which, contrary to assumption, is not the only home of the motorcycle jacket. One of the most esteemed makers, D. Lewis, was established 123 years ago in the UK as a tailoring business. By the 1950s, the company had become the essential makers of the motorcycle jacket on the British side of the pond, despite seemingly taking inspiration for its model names – The Highway Patrol, The Plainsman and The Bronx among them – from the other side. Brando and James Dean wore Perfecto, but John Lennon, Mick Jagger and Steve McQueen, not to mention the Sex Pistols, The Clash and Motörhead, wore Lewis, as did the hard men of speedway and TT races. The Atlantic gap is reflected in the designs: the signature red lining aside, Lewis’s jackets have typically come with action pleats and a leather-covered belt buckle, because while motorbikes in the US were traditionally ridden in the ‘sit up and beg’ position, British riders crouched low over their petrol tanks. And they definitely did not want to get those scratched.

“The bottom line is that, although there is more technically advanced clothing to wear for riding a motorcycle today, it doesn’t look as good as the classic style,” says Derek Harris, the managing director of Lewis Leathers, which has a nine-month waiting list of orders. “Whether in Europe or the US, [the motorcycle jacket] belongs to a pioneering age of motorised transport that came with a much greater risk to life. Just to put one on suggests bravery, not menace – the early riders were anything but menacing.

“But then the perception of the motorcycle jacket keeps changing,” Harris adds. “Society has since ingested the notion of the motorcycle jacket as a symbol of the bad boy. Now, younger generations probably don’t even make that association – it’s just the latest thing to wear. But if you look closely at the fashion versions, there’s no weight to them, there’s no substance. And that’s never been what a real motorcycle jacket is about. The real thing has heft, it has presence.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 38 of The Rake.