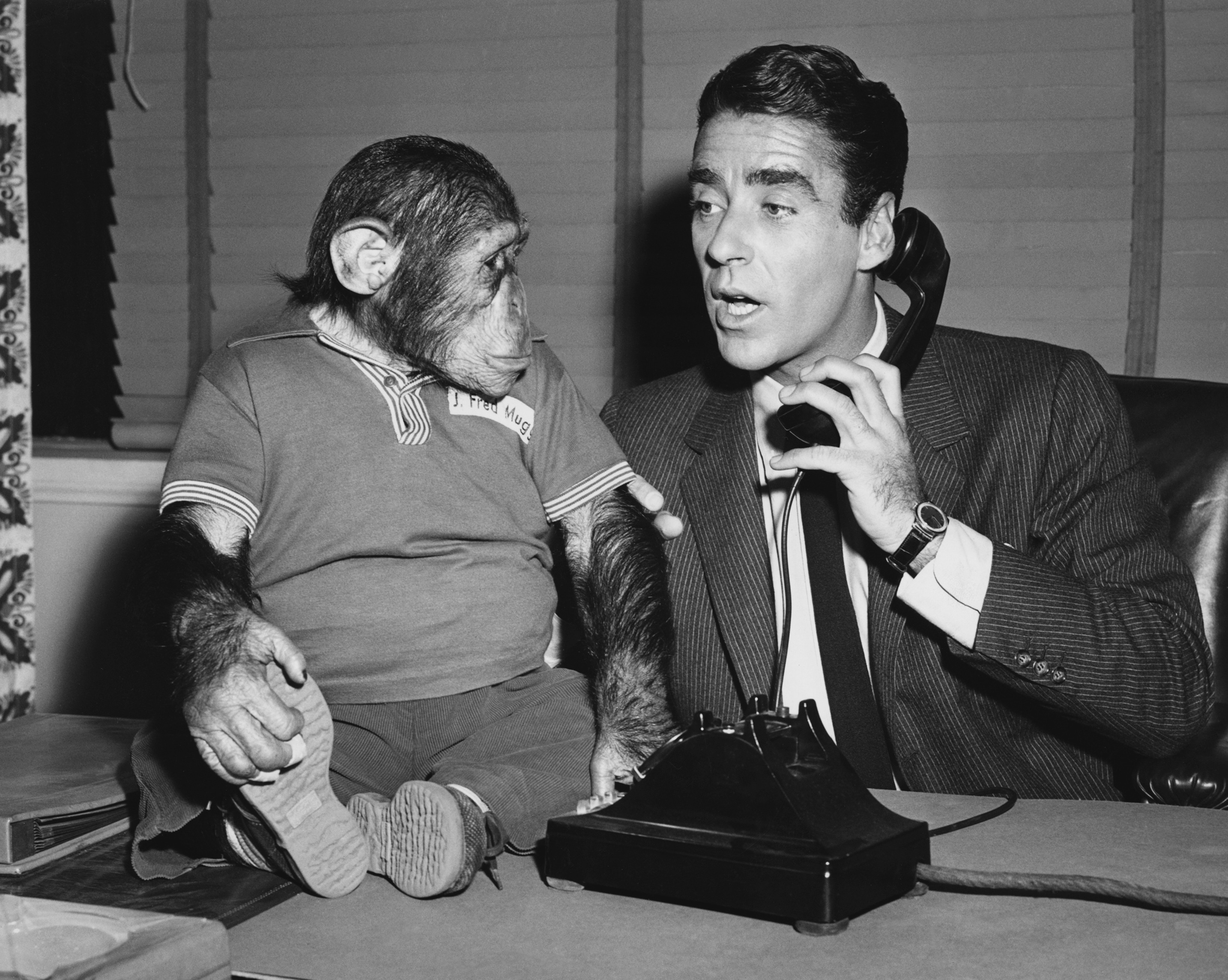

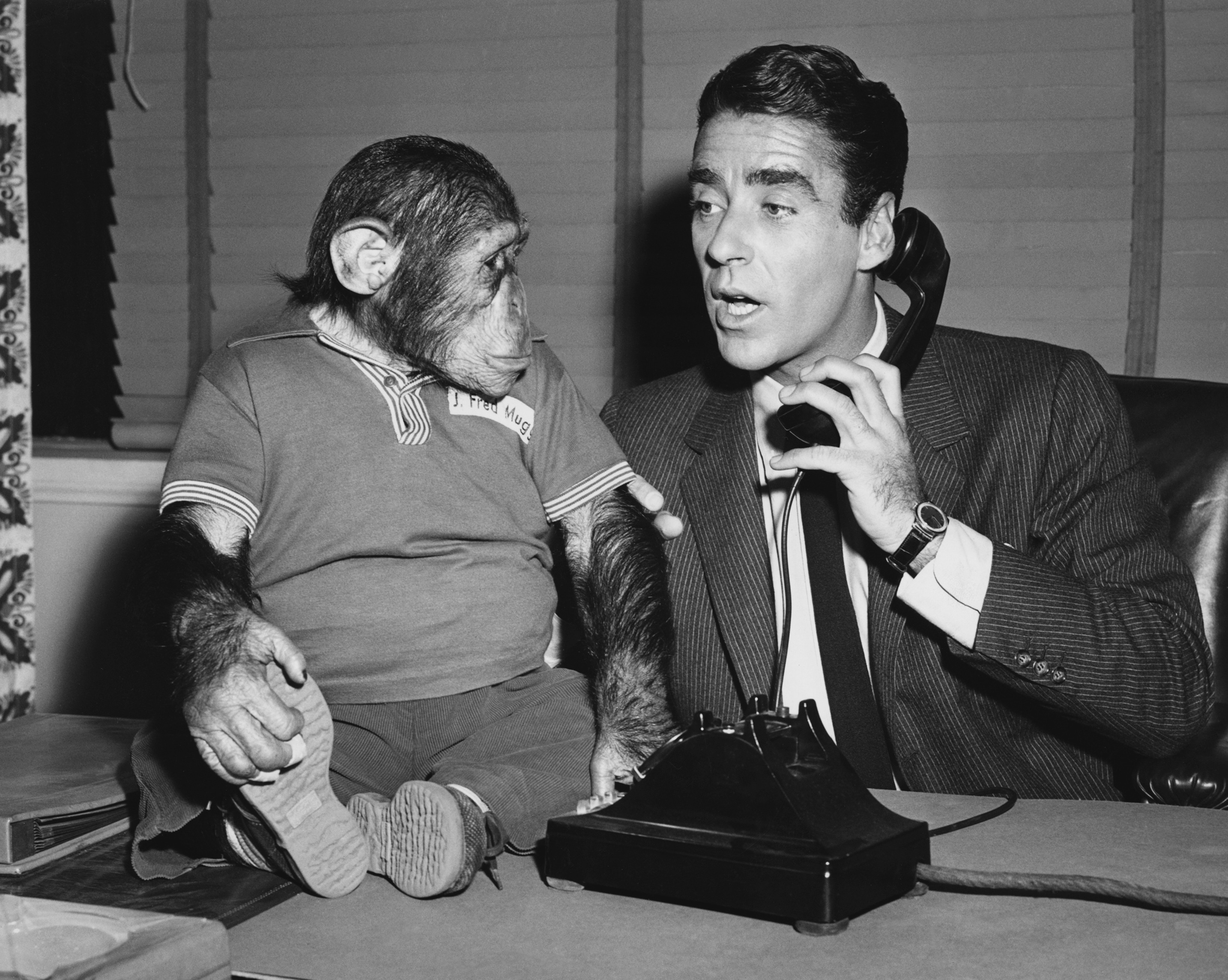

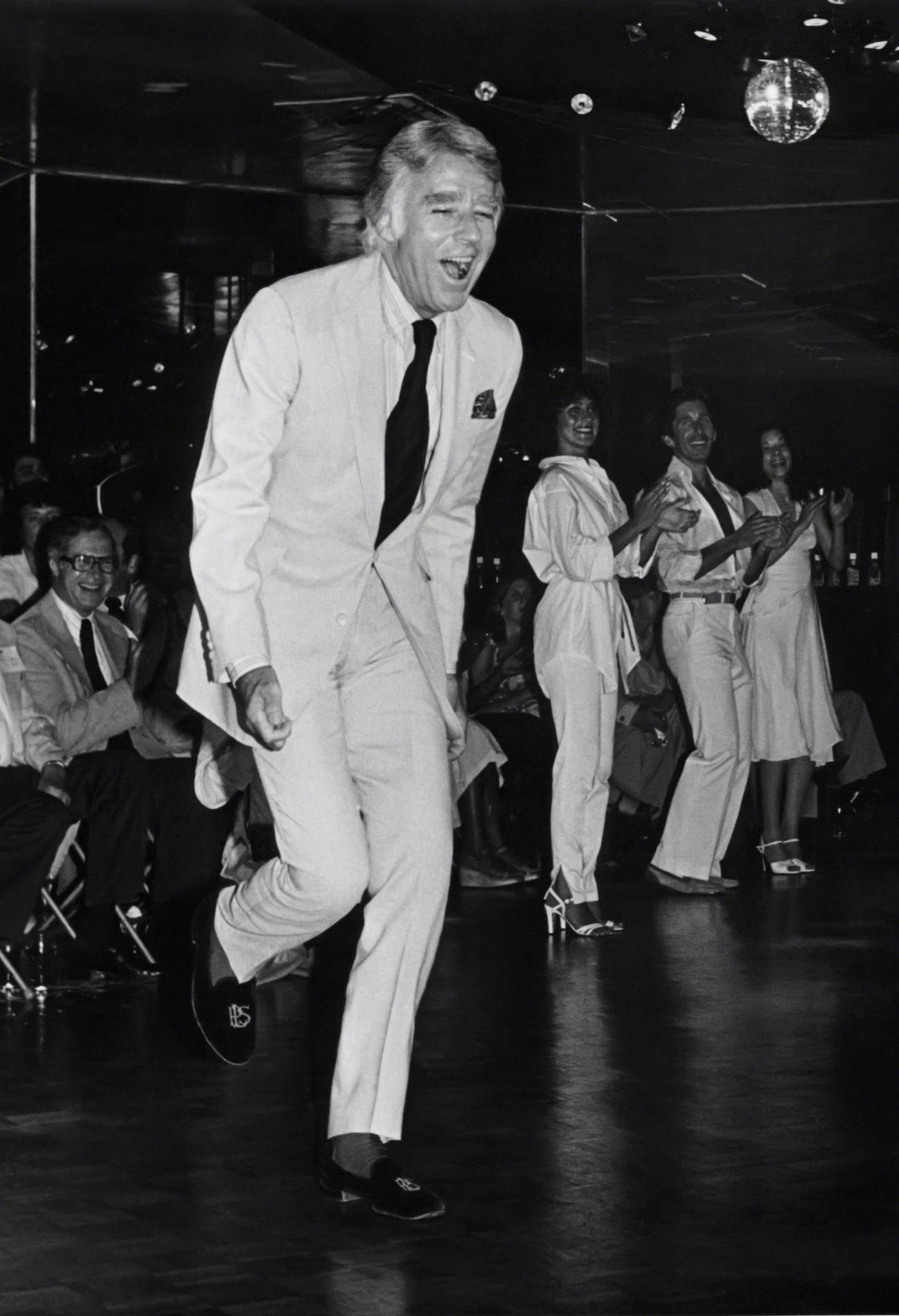

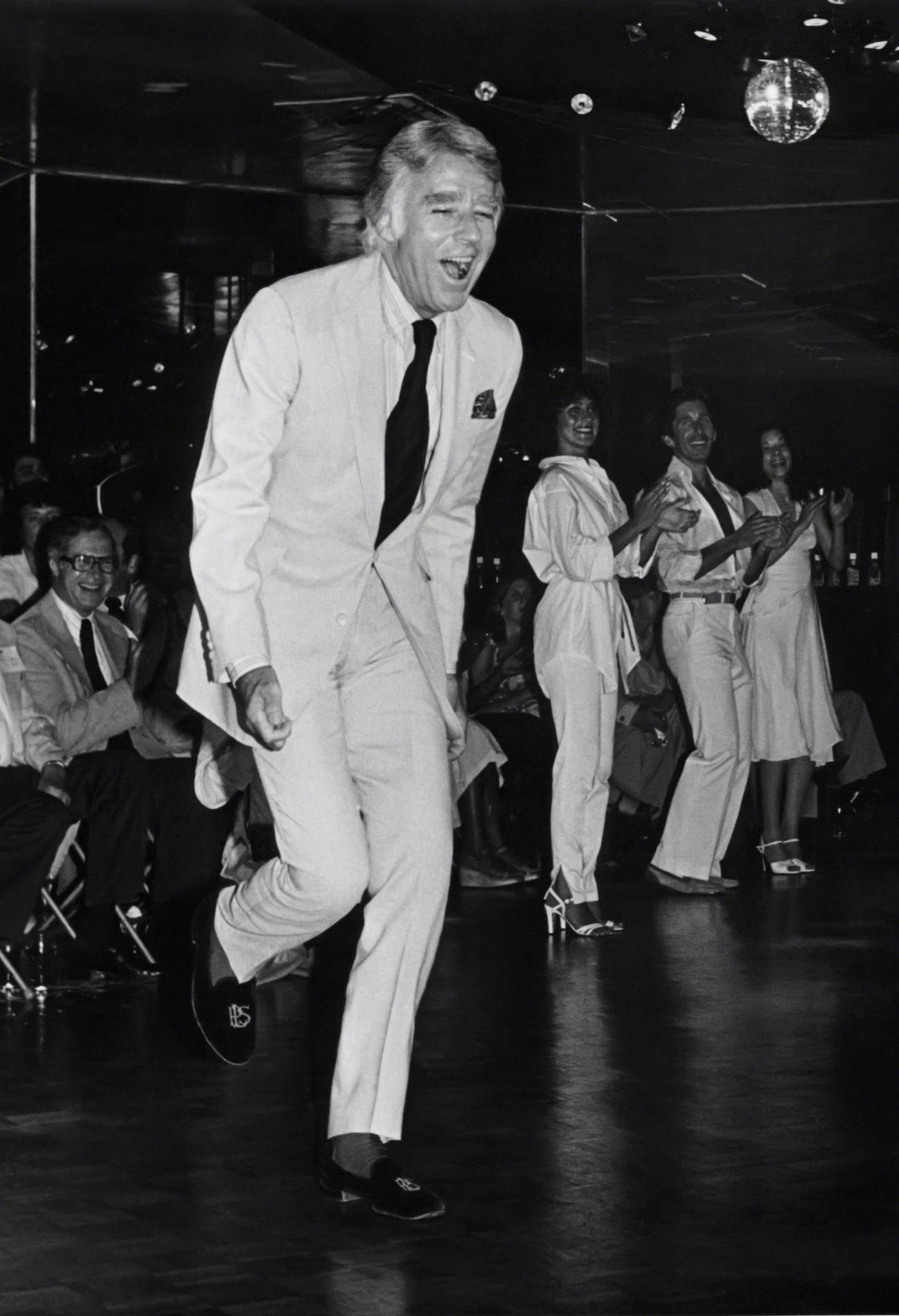

Follow Suit: Peter Lawford

He was born in inauspicious circumstances, and died impoverished at the age of 61. In between, Peter Lawford conquered Hollywood, but the charming, boyish insouciance was surely skin-deep.

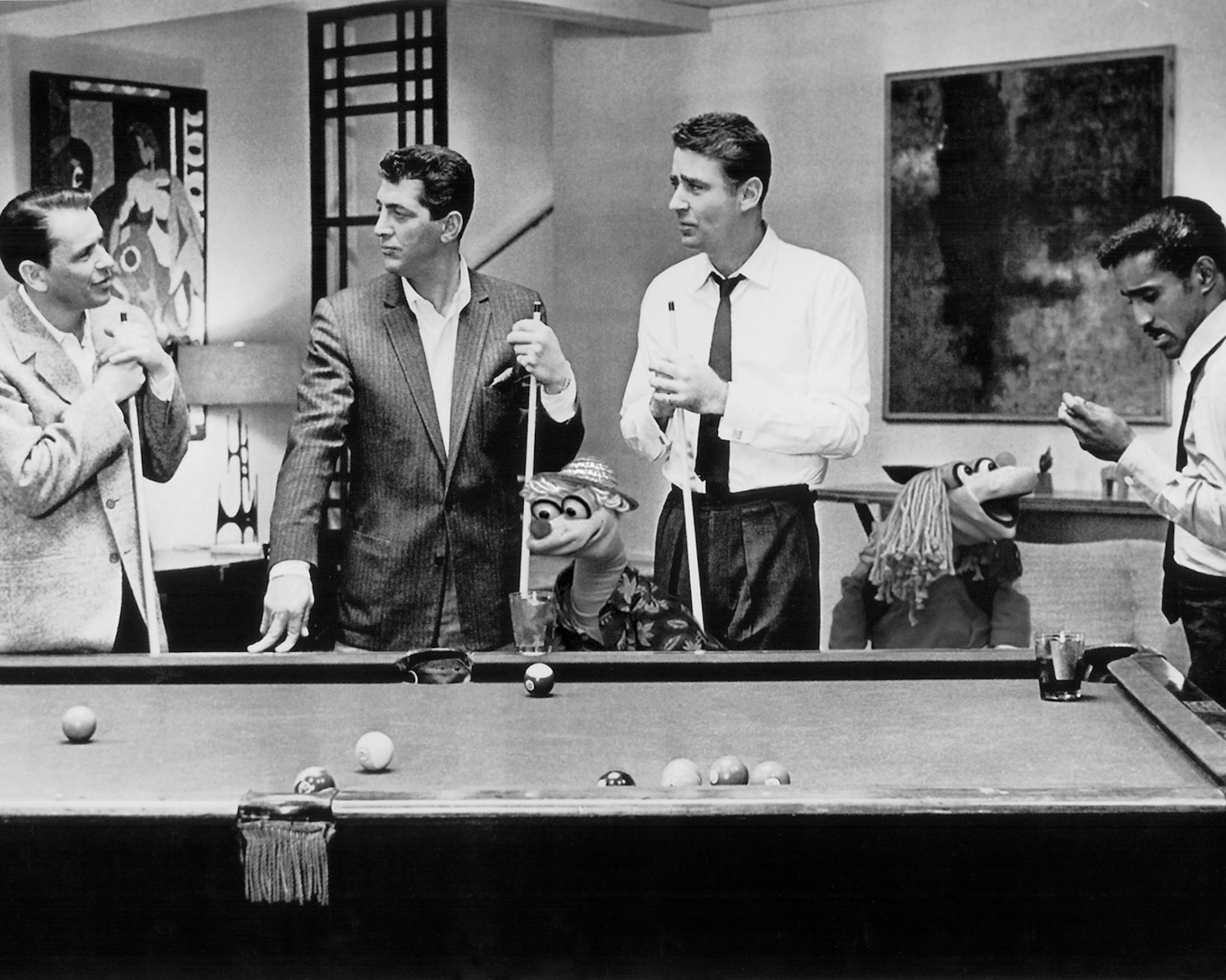

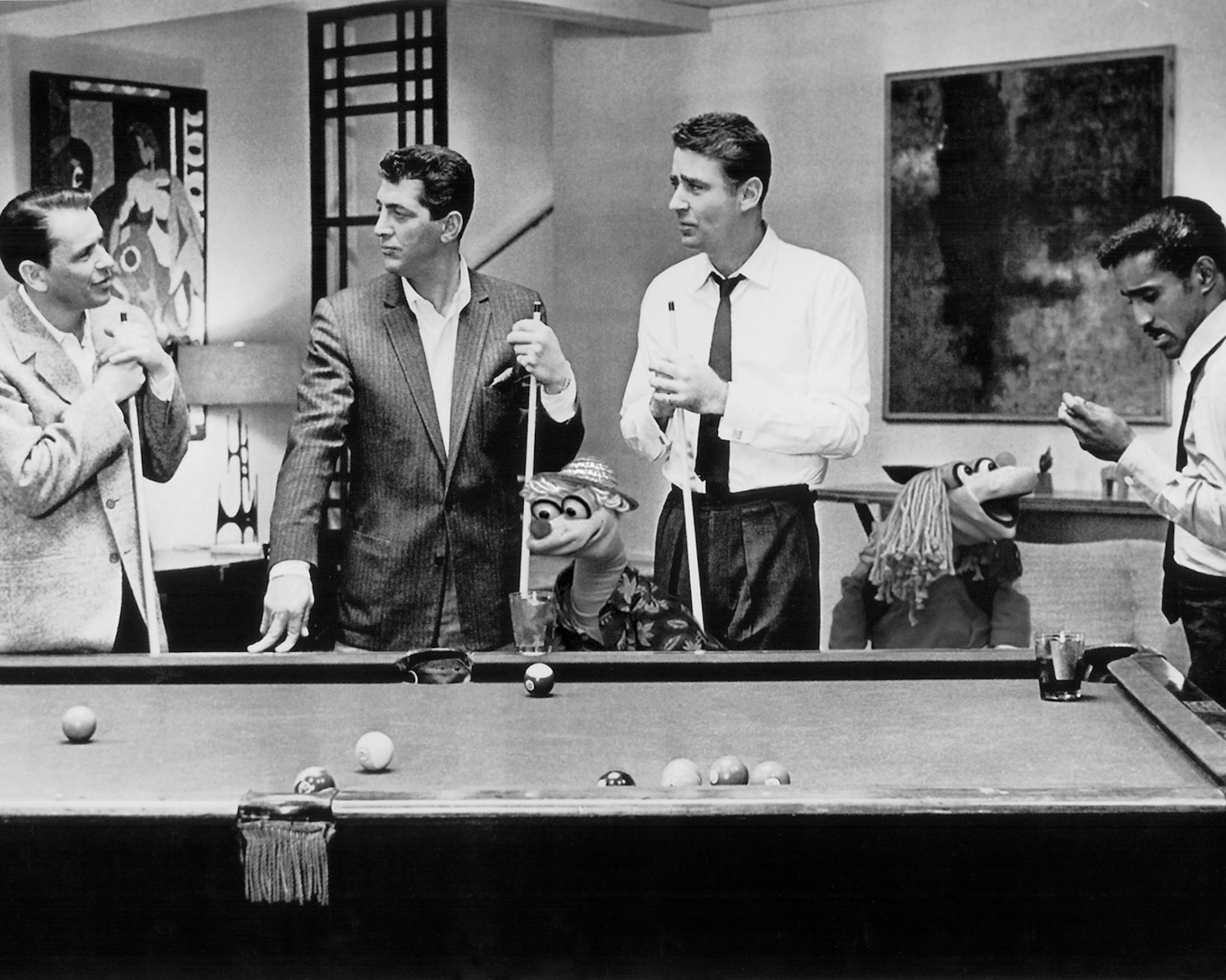

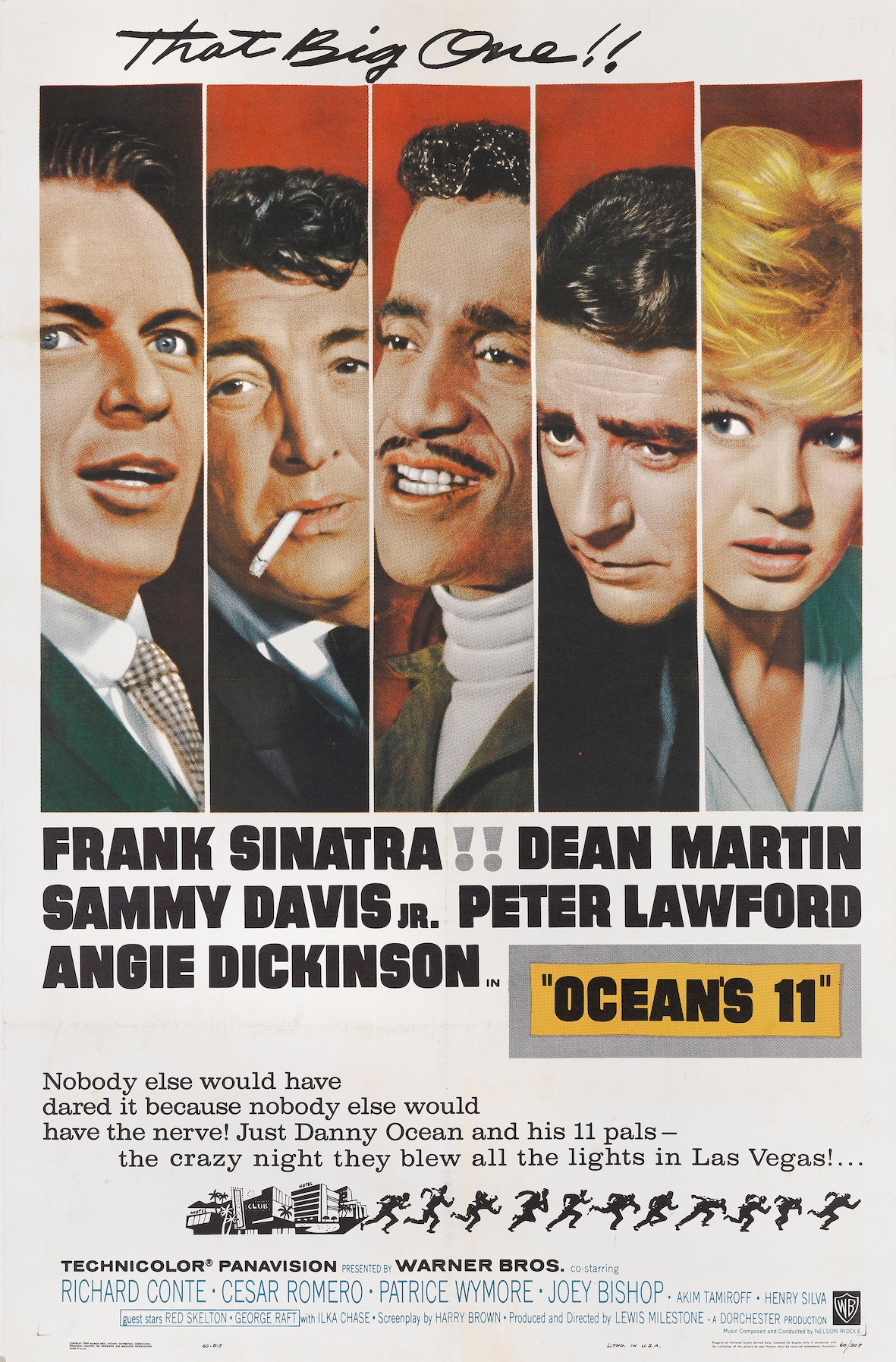

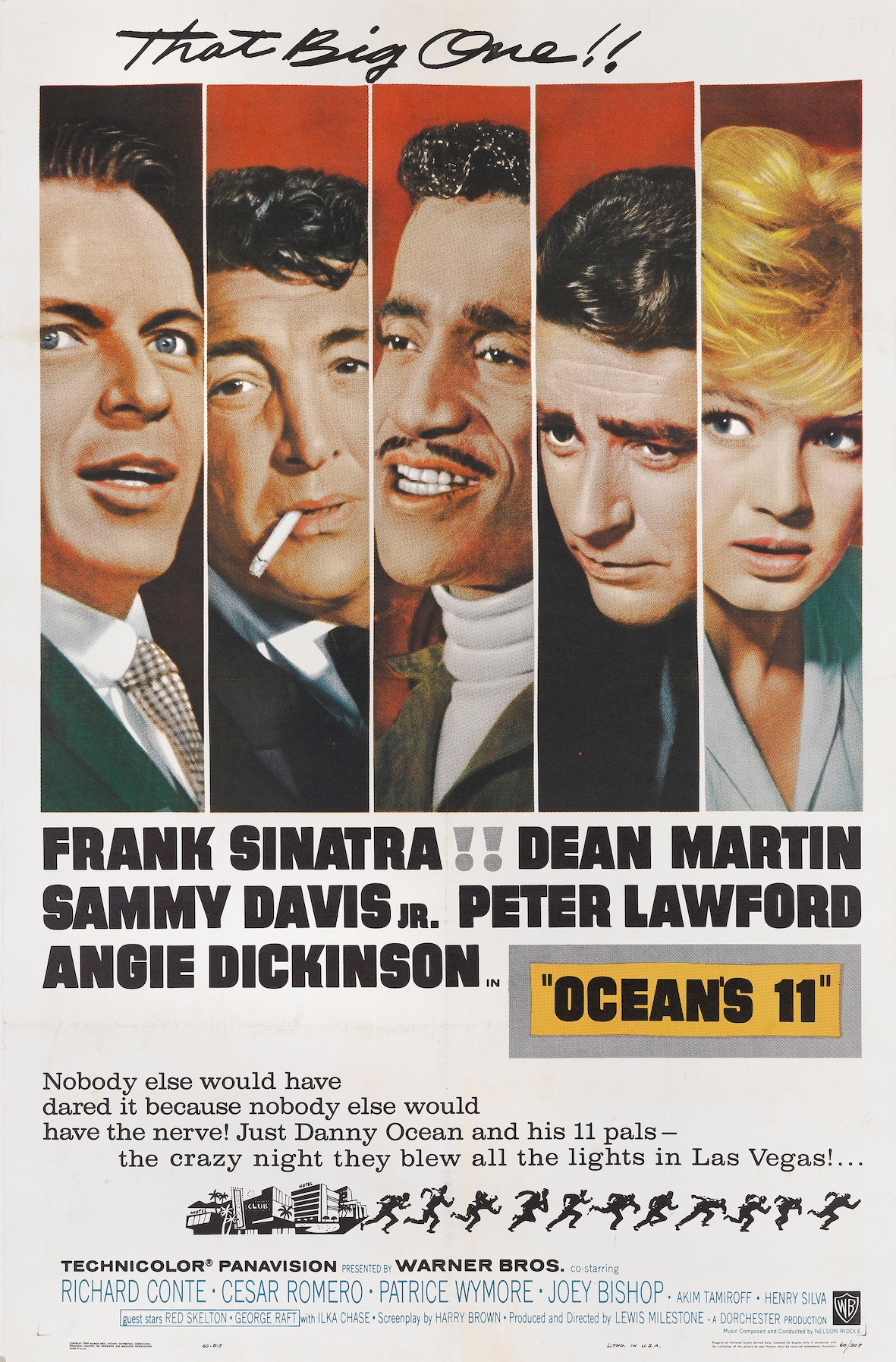

I was a halfway-decent-looking English boy who looked nice in a drawing-room standing by a piano.” So quipped the man born Peter Sydney Ernest Lawford in London in 1923, referring to a Hollywood career arc that reached its apogee in 1960, when he starred with his fellow Rat Packers in the Ocean’s 11.

Not only does Lawford’s demure assessment omit the part his preternaturally good looks and nonchalant baritone played in helping him carve a showbiz niche, it excludes various disadvantages that made his rise to stardom — and marriage into the most high- profile family in American history — borderline miraculous. Factor in other complications in Lawford’s life, and his dashing insouciance seems like denial at its most sophisticated and convincing.

Not only does Lawford’s demure assessment omit the part his preternaturally good looks and nonchalant baritone played in helping him carve a showbiz niche, it excludes various disadvantages that made his rise to stardom — and marriage into the most high- profile family in American history — borderline miraculous. Factor in other complications in Lawford’s life, and his dashing insouciance seems like denial at its most sophisticated and convincing. Lawford’s father was Sydney Turing Barlow Lawford, a major-general in world war I who commanded the 22nd Brigade and the 41st Division, was knighted in the field, and given the nickname ‘Swanky Syd’ for his tendency to sport full dress regalia, including his medal entitlement, after the Great War. So far, so good.

However, Lawford was the result of an illicit tryst his 58-year- old father had with the wife of a colonel 18 years his junior, causing the breakdown of both marriages. His parents’ union occurred only after a long and excruciating breech birth, forcing the newly formed family to flee to the United States via France in the 1930s.

Reports of his mother’s ambivalence towards him, of swings between a smothering and neglectful approach to parenthood, are rife; other rumours have the young Lawford being dressed as a girl and sharing his parents’ bed until he was 12; still more rumours concern allegations of sexual abuse by various governesses and an uncle. Where reports of Lawford’s penchant, later in life, for sadomasochistic sex fit into this is unknown.

It was in the latter stages of his turbulent and itinerant childhood, aged 14, in a spa hotel in France, that Lawford severely damaged his right arm, a jagged shard of glass slicing through its upper reaches when he tried to barge his way through a locked door. The resulting irreversible nerve damage compromised his movement, a disability he would later become adept at concealing on stage and on camera. The disability also protected him from the draft for world war II.

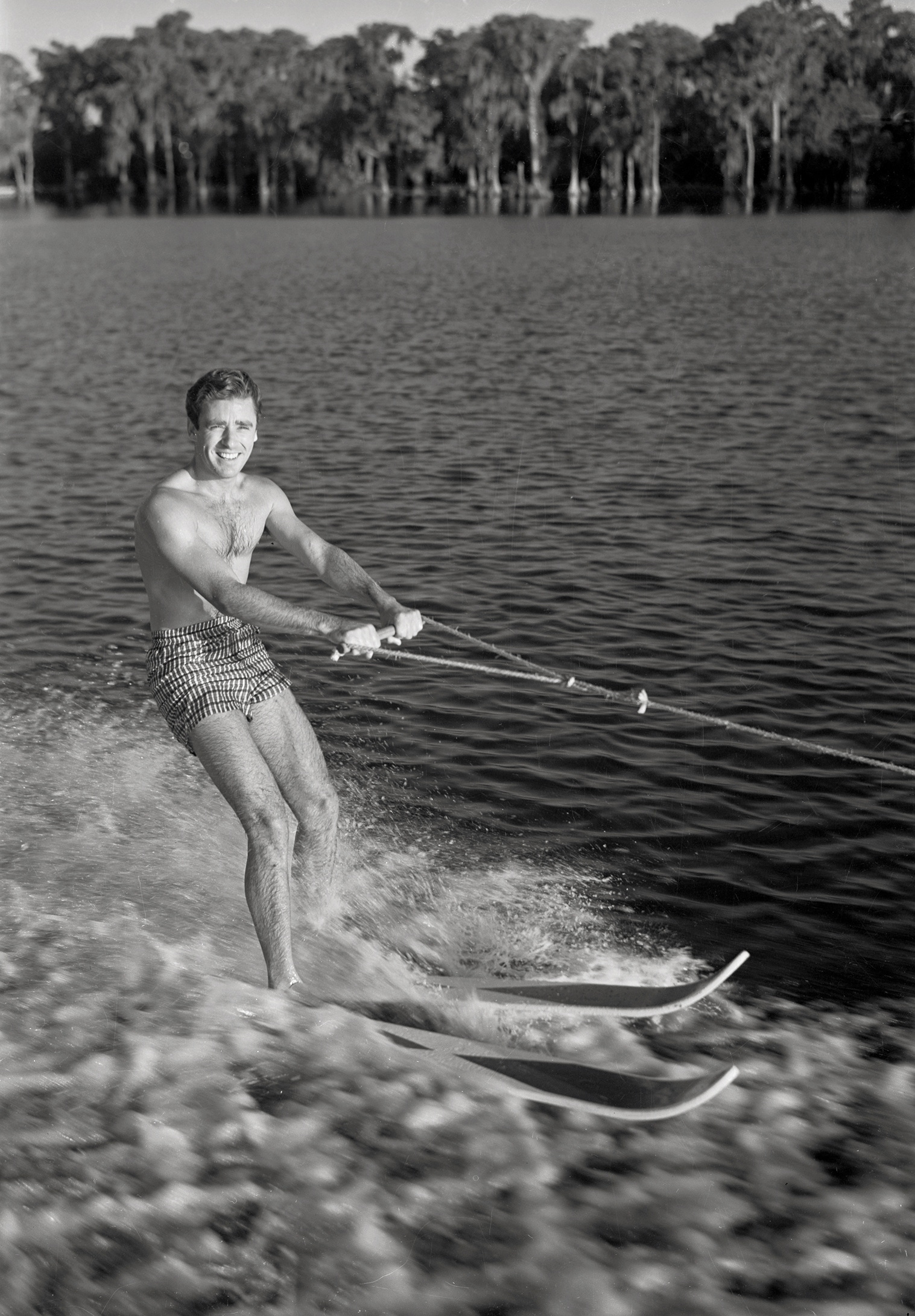

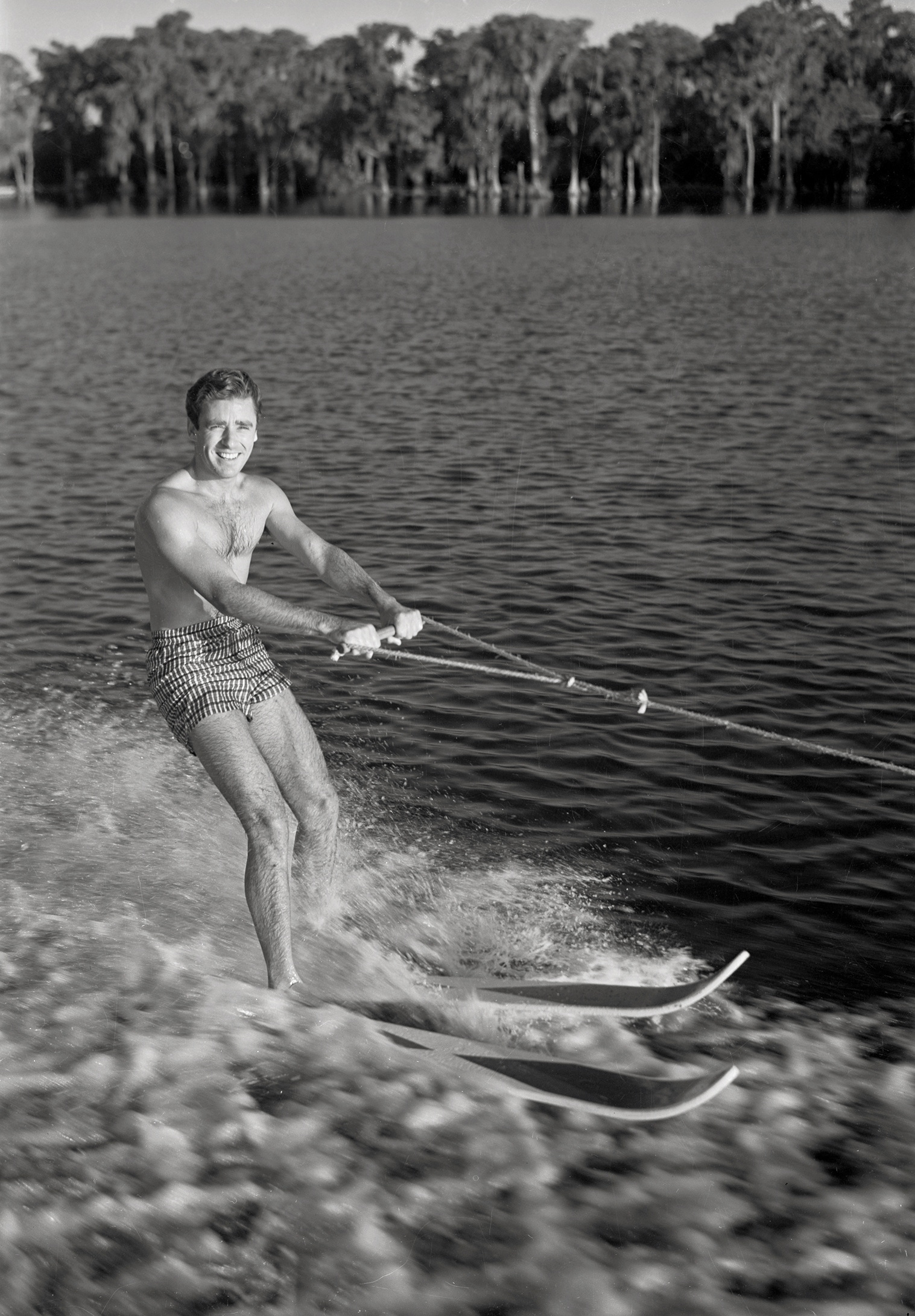

A period in Florida followed, during which he was called upon to support his family, his father having lost his fortune — he worked parking cars at the social club frequented by the family to which he would one day belong: America’s First, the Kennedys (one account has him fired for sharing a Coke and a sandwich with a young black child, shading under a tree, during a break). “I was old enough when [the hard times] came along to learn from them, and young enough to accept them as part of the plan,” Lawford said, relatively late in life, of this period of his youth. Having earned enough to head for the hills — Hollywood’s — he was spotted, and started attending the casting calls. In Tinseltown in that era, he had a distinct advantage — Englishness smacked of heroism precisely because of the war effort against Hitler that Lawford had narrowly avoided — but it was a Peter Lawford fraught with insecurities who charmed cinemagoers as he forged a path to the top of the Hollywood bills, one smoothed by Clark Gable being drafted into the war, with his starring turns in musicals such as A Yank at Eton (1942), The White Cliffs of Dover (1944), and later Good News (1947), Easter Parade (1948), and in the same year Julia Misbehaves (in which he became the first man to kiss Elizabeth Taylor on screen).

His mother remained a mendacious presence in his life, at one point calling in at the offices of Louis Burt Mayer, the co-founder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, to tell him her son was homosexual, a claim supported by his epicene mannerisms but undermined by his already prolific womanising on the showbiz circuit.

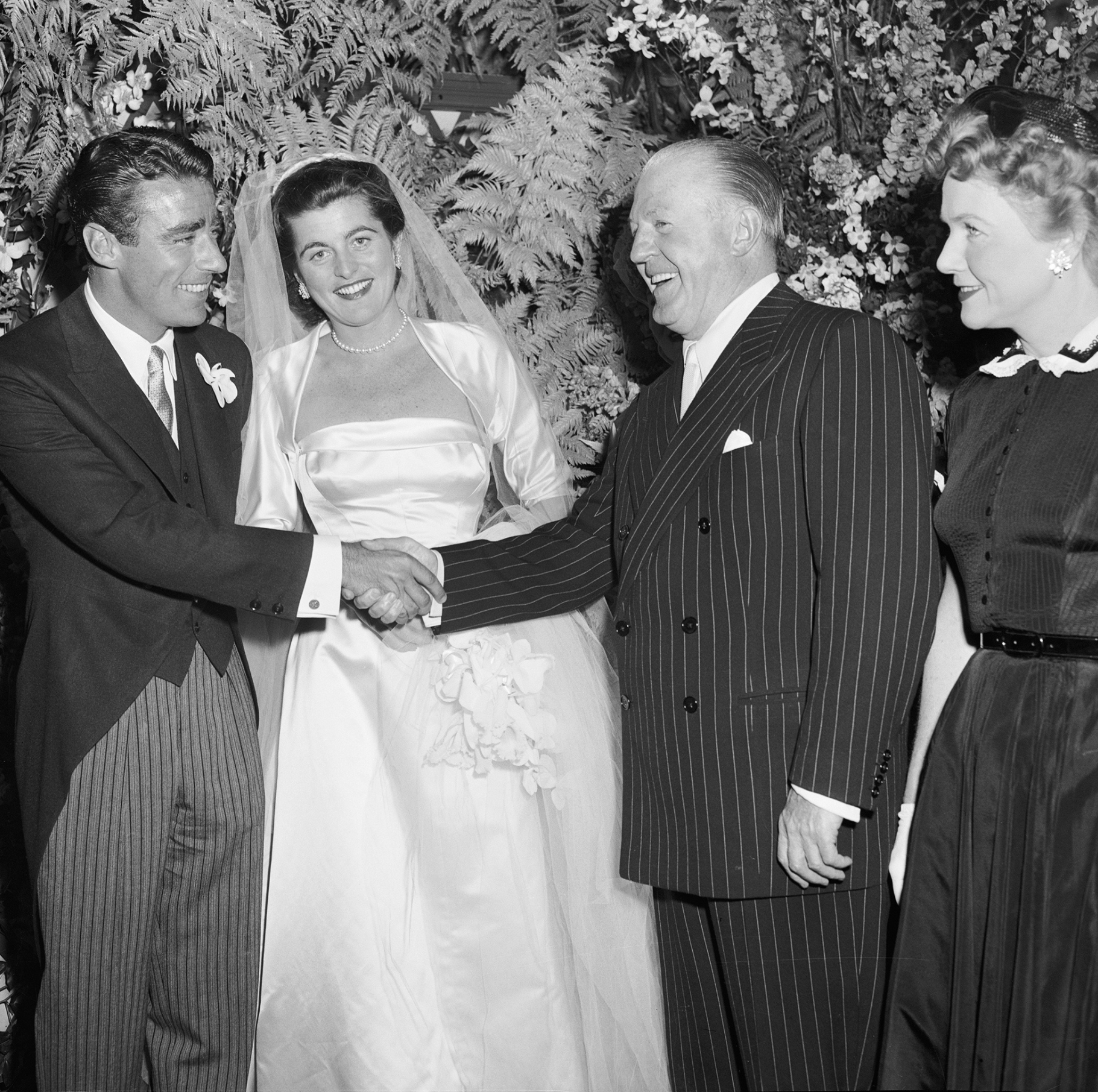

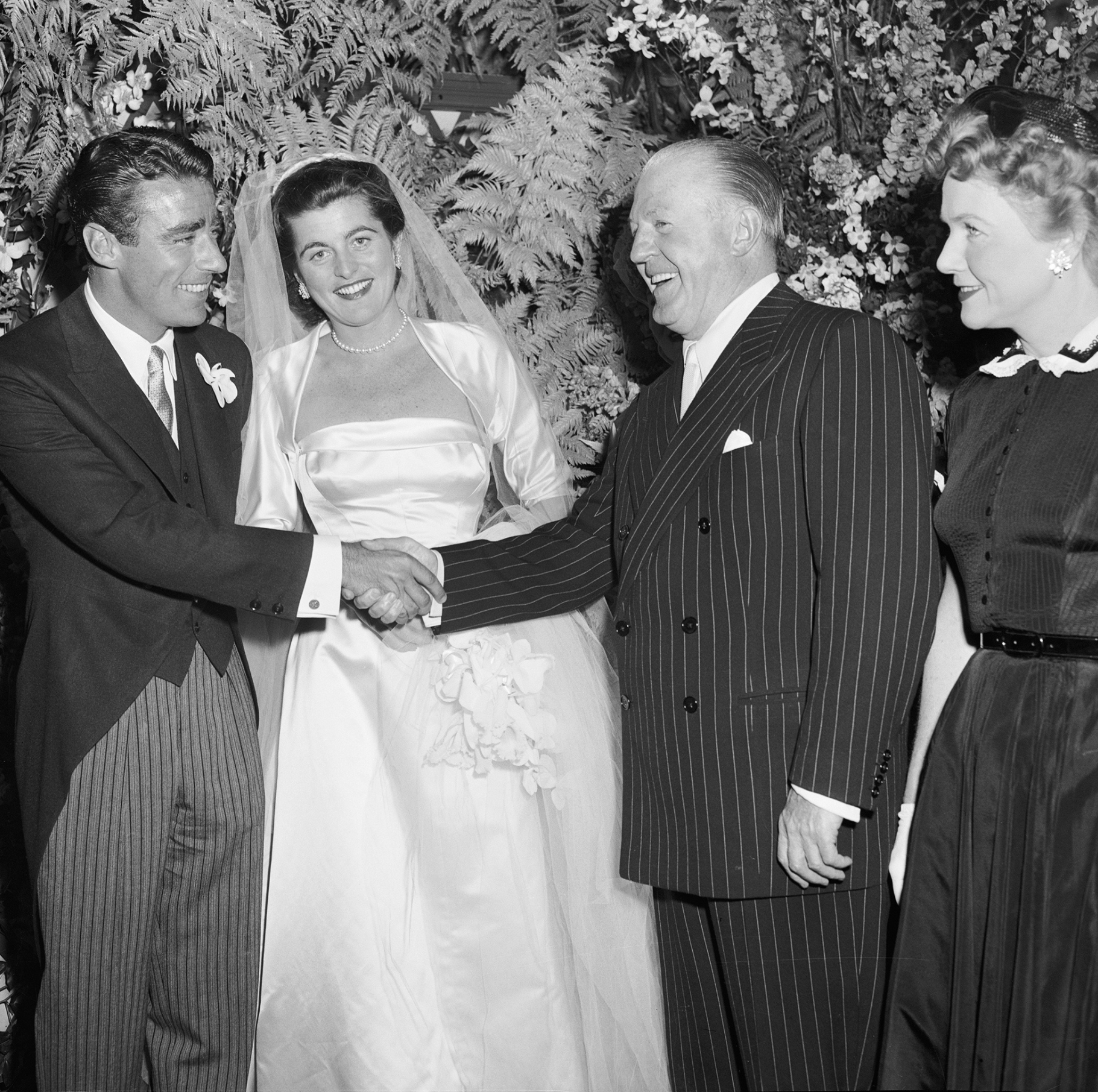

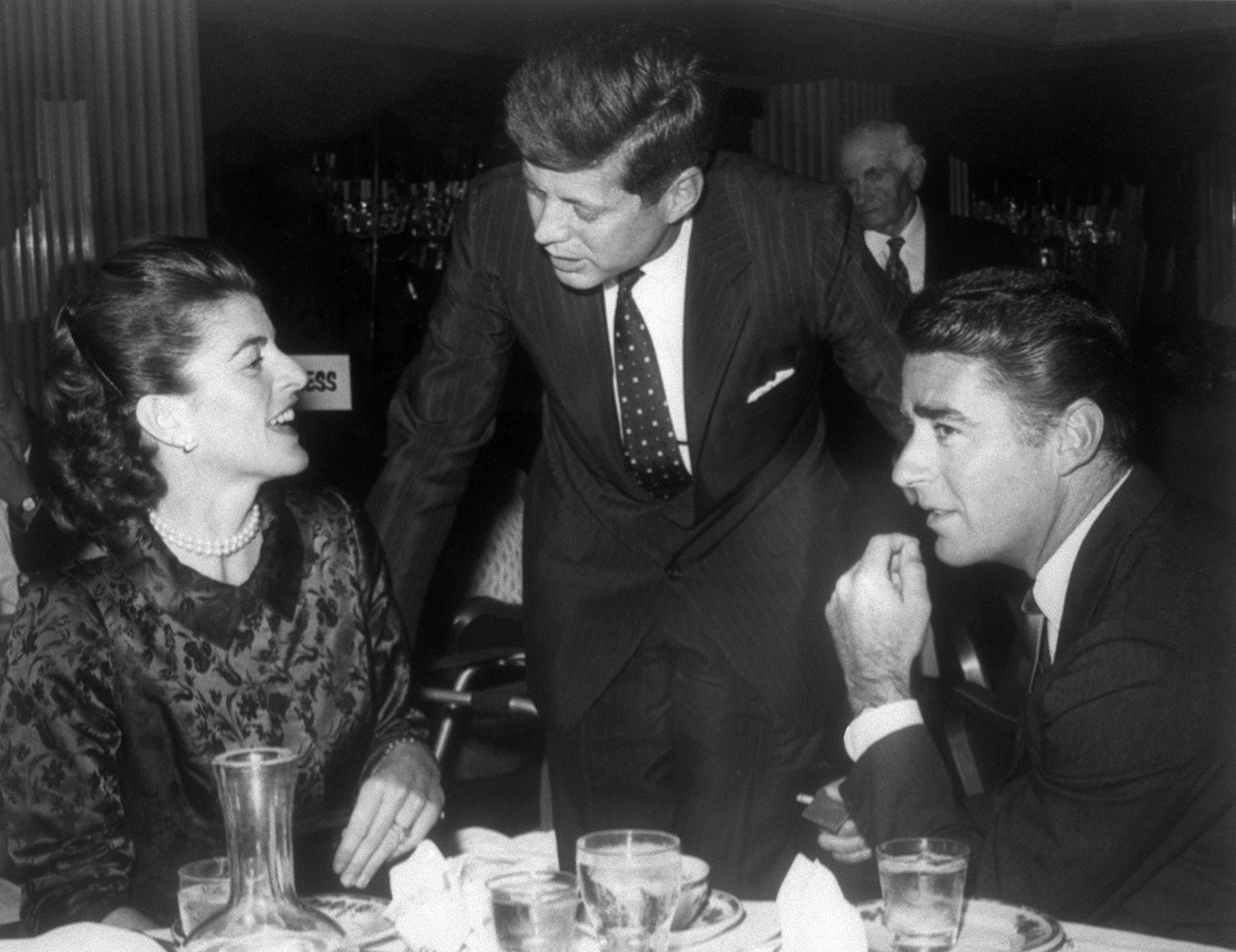

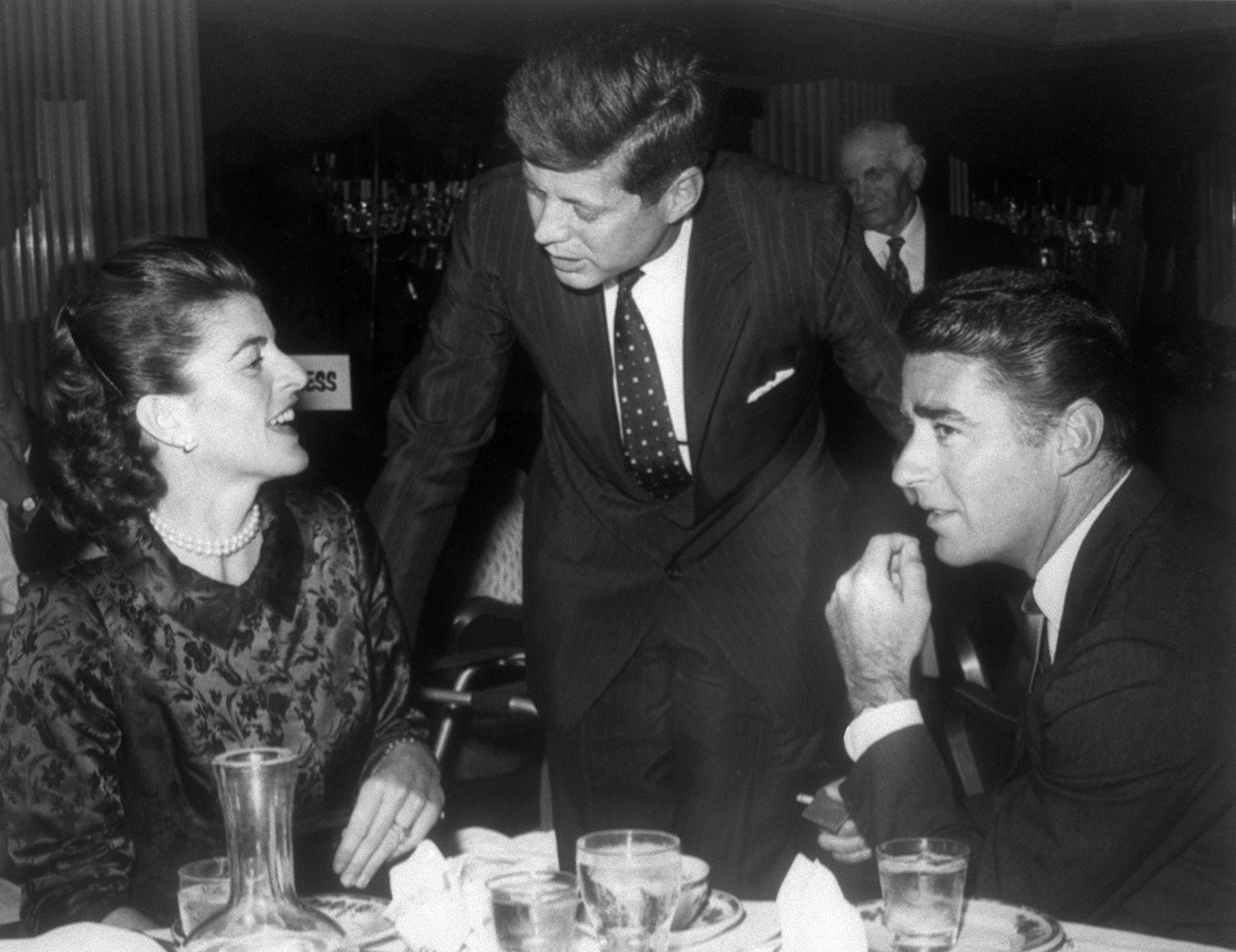

An affair with the African-American actress Dorothy Dandridge caused some scandal but didn’t derail a career on which the limelight shone all the brighter when he married Patricia Kennedy, the sister of the man who would one day become the 35th president of the United States. This marriage — the first of four in his life — also wed Lawford’s showbiz kudos to newfound political influence (he would one day introduce Marilyn Monroe to J.F.K.), an overlapping of his spheres of influence that prompted the rest of the Rat Pack, when he joined that group of wild carousing Las Vegas entertainers five years later, to nickname him Mr. Fix-It.

Frank Sinatra coined a more pejorative moniker — ‘Brother- in-Lawford’ — and there was a jealous tinge to the banter (Dean Martin once quipped, “I bet J.F.K. never calls you at 3am unless it’s to borrow a suit for his inauguration!”). That tinge was arguably always going to turn nasty, and an acrimonious falling out with Sinatra, with whom he’d forged a friendship after working with him on It Happened in Brooklyn in 1947, was always lurking around the corner.

A seven-year hiatus had already blighted their friendship, due to suspicions harboured by Sinatra during his divorce from Ava Gardner (perhaps not unreasonable, considering Lawford would eventually count Rita Hayworth, Lucille Ball, Anne Baxter, Gina Lollobrigida, Judy Garland, Grace Kelly and Kim Novak, as well as Dandridge, on what might crassly be called his C.V.).

As for the final, irreparable bust-up, that arose due to J.F.K. having occasion to stay at Sinatra’s Palm Springs house — Sinatra had excitedly built a helipad in the grounds — until the president decided it was inappropriate, as a mafia boss had stayed there recently, and opted to bunk down at Bing Crosby’s place instead.

So incensed was Sinatra by Lawford’s failure to sway the president to come and stay at his ‘West Coast White House’, as he called it, he reportedly only ever contacted Lawford again when his son was kidnapped in 1963. “There was no hello, no apology, nothing like that,” Lawford later recalled. “He just said for me to call Bobby and get the F.B.I. in on the case and get back to him in Reno.”

There’s little record of how this affected Lawford emotionally, but what we know, pieced together, paints a fairly bleak picture. Lawford’s star never fully recovered from a feud that left him excluded from the Pack and relatively isolated in Hollywood. Alcohol and drug abuse depleted his ability to sing and act, and a period of relative anonymity leads up to a final chapter of his life in which he marries a woman 35 years his junior, souses himself in vodka on the plane to the Betty Ford clinic in California, then beats the clinic’s strictures by having cocaine delivered by helicopter to the desert behind the facility, for consumption between bouts of bridge with fellow patients Liz Taylor and Johnny Cash. He died just before Christmas 1984 at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Perhaps one of the most convincing tearful clowns in showbiz history, Lawford once said of his unruffled demeanour on stage and on camera: “It isn’t that I’m bored, it isn’t that I’m blasé. I just like to hang loose.” Still waters run not only deep, it would seem, but can be tempestuous beneath the surface, too.

Photo credits: Getty Images