Theatre of War

Mention Hollywood’s contribution to the Allied effort in world war II, and many will think of propaganda newsreels, feelgood fiction and titillating mess-tent entertainment. But, writes NICK SCOTT, a surprisingly large number of stars answered the call of duty and threw themselves into the action...

The role of the movies in world war II is the stuff of legend. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to cinemas as “a necessary and beneficial part of the war effort”, prompting picture houses to host ‘bond drivers’ (campaigns to sell U.S. treasury bonds to finance the war effort) and place collection bins for scrap metal and rubber in their lobbies. Once seated, audiences were shown newsreel updates from the frontlines and stirring combat footage as well as movies influenced by the 32nd U.S. president’s other assertion — that with every production, Hollywood should ask itself, Will this picture help win the war?

Roosevelt even established the Office of War Information (O.W.I.) to promote the war effort. The O.W.I. issued guidelines to filmmakers and reviewed scripts and early cuts of films, ensuring that what emanated from projectors would conjure up a romanticised image of an American society united against the enemy. The result was movies such as Casablanca, starring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman.

Tinseltown’s costumes and props were used by the U.S. army’s tactical deception unit the Ghost Army, and even Disney got in on the act, designing military emblems, making propaganda reels, and dressing its biggest star of the moment, Donald Duck, in khakis. But while Hollywood’s considerable contribution to the war effort is well documented, perhaps a more intriguing truth is just how many stars of the silver screen were involved in the thick of the action.

It seems apposite to begin with James Stewart, as he was the first major Hollywood actor to be drafted into the military during the war (having piled on the pounds to pass the medical). Stewart had already completed nine months of training at Moffett Field, California, clocking up 400 logged flight hours and completing his extension courses, when the Japanese military’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor drew the U.S. into the war the following day.

In the autumn of 1943, Stewart was assigned to the 445th Bombardment Group in Britain, and flew more than 20 combat missions, including bombing raids over Germany. By the time of his post-war screen career — notably It’s a Wonderful Life, Rear Window, and The Spirit of St. Louis — he was the recipient of a Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal and Bronze Star. The only actor in history to be bestowed honours by both the Ministry of Defence Medal Office and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, he was ranked colonel by the end of his service.

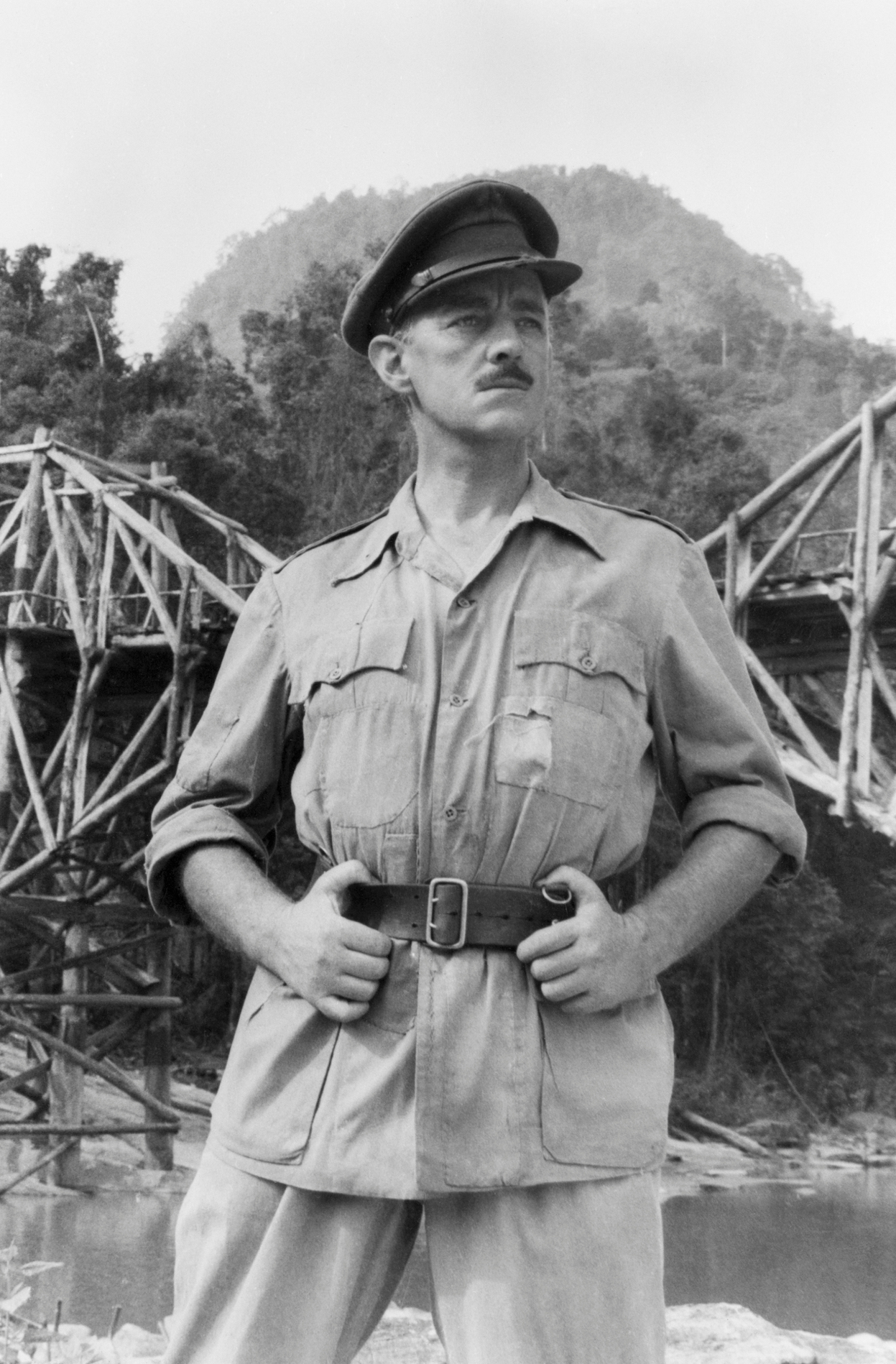

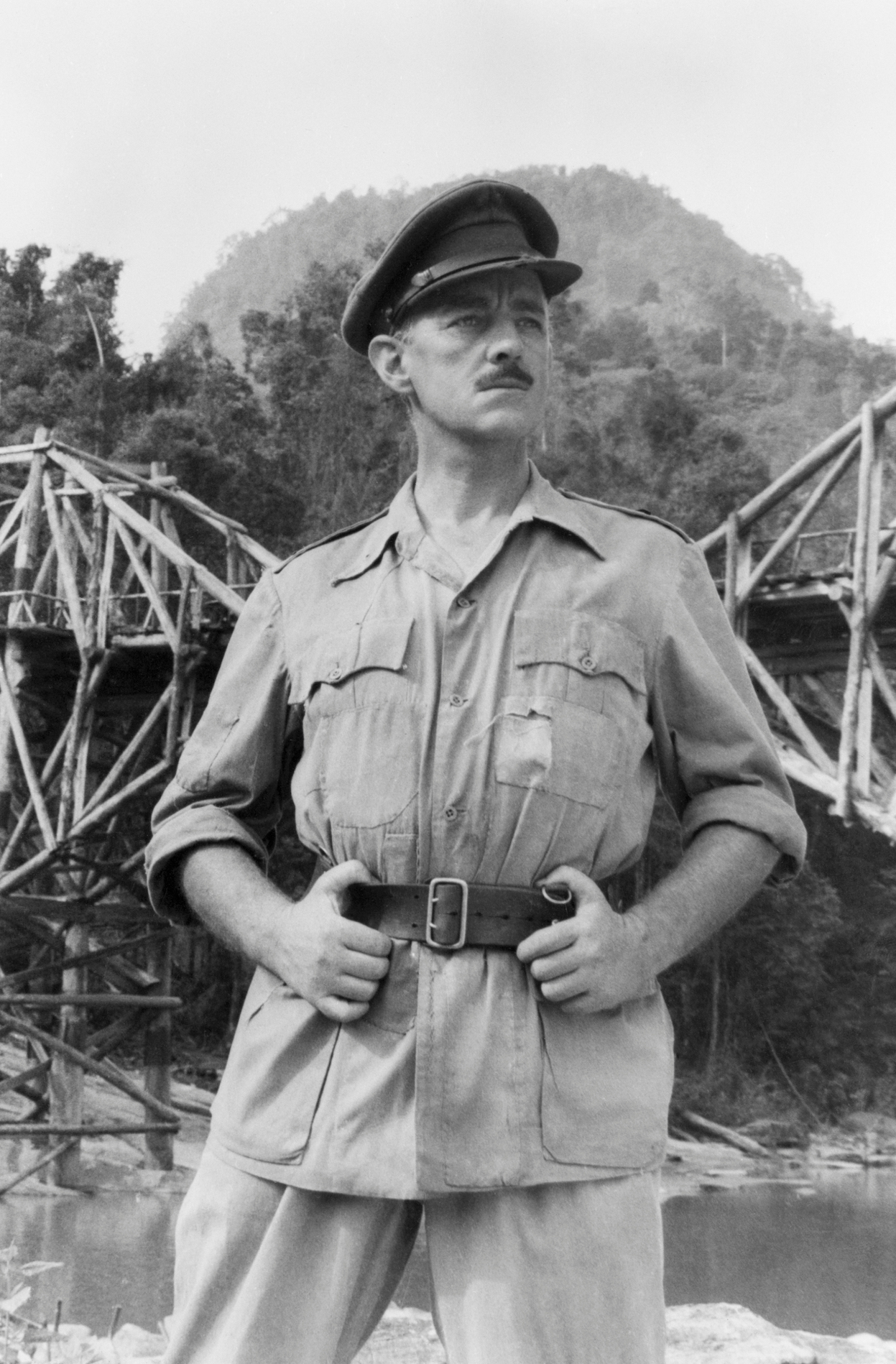

Another screen legend with a movie career either side of his world war II service was David Niven. The silver-tongued raconteur had attended the Royal Military College in Sandhurst, where he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Highland Light Infantry before resigning his commission after two years stationed in Malta and making his way to Hollywood via New York. By then he’d played numerous roles, including Dodsworth (1936), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), The Prisoner of Zenda and the 1939 adaptation of Wuthering Heights, in which he shared top billing with Laurence Olivier.

Then, one morning in September 1939, with three more weeks of filming to go on the crime-comedy caper Raffles, he was in a boat moored at California’s Balboa Yacht Club, sleeping off a major rum session with fellow British actor Robert Coote, when his louche Englishman abroad existence was rudely interrupted. Over to Niven’s autobiography, The Moon’s a Balloon, for the next stage of the story:

“We were woken up at 6 a.m. by a man in a dinghy banging on the side of our boat.

‘You guys English?’

We peered blearily over the side. ‘Yes.’

‘Well, lotsa luck — you’ve just declared war on Germany.’

We never spoke a word... just went below and filled two teacups with warm gin.”

Determined, along with Cooke and Olivier, to return home and enlist, he had to get his brother to send a cable that read, “Report regimental deport immediately Adjutant” in order to convince studio executive Samuel Goldwyn to release him from his Raffles contract. Weeks later he was recommissioned into service as a lieutenant with the Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own).

“I don’t want to look like some semi-hero,” he told The Dick Cavett Show. “I certainly wasn’t. There was nobody more terrified than me.” A pause. “I got the Iron Cross, though.”

I don’t want to look like a hero. There was nobody more terrified than me. I got the Iron Cross, though.

Determined, along with Cooke and Olivier, to return home and enlist, he had to get his brother to send a cable that read, “Report regimental deport immediately Adjutant” in order to convince studio executive Samuel Goldwyn to release him from his Raffles contract. Weeks later he was recommissioned into service as a lieutenant with the Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own).

His acting talent was only a small portion of his contribution, although he wasn’t one to expound on his grittier experiences. “I don’t want to look like some semi-hero,” he told Cavett in that same interview. “I certainly wasn’t. There was nobody more terrified than me.” A pause. “I got the Iron Cross, though.”

It was in far more sombre, as well as sober, circumstances that Clark Gable found himself enlisting in the U.S. Army airforces. His wife, the actress Carole Lombard, was on a successful tour to sell war bonds (having sold $2m worth in a single day) when her plane crashed into Potosi mountain, about 32 miles south-west of Las Vegas, killing all 22 people on board (including Gable’s agent). Her final words to him, allegedly, were, “Pappy, you’d better get in this man’s army”.

An acting contemporary who might relate to that serendipity was Paul Newman, who once said that, “A man with no enemies is a man with no character”, a proclamation that may well have arisen from his experiences as part of the crew aboard aircraft carrier U.S.S. Bunker Hill and its exploits in the Pacific theatre. The man who would become the star of Cool Hand Luke (1967) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) had enlisted in the navy aged 17 in 1943, colour blindness dashing his hopes of being a pilot. He was acting as a turret gunner during the Battle of Okinawa when his squadron suffered heavy losses in a kamikaze attack — but for his pilot having an ear infection, he would have been involved in the battle during which the incident occurred.

Sir Alec Guinness, whose combat exploits in a galaxy not so far from here began when he participated in the Allied invasion of Sicily, also seems to have been hand-held by a guardian angel. Guinness enlisted in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve — not yet a film star but already a titan of the London Shakespearean stage scene — in 1941. During Operation Husky, part of the Allied invasion of Sicily, Guinness, in his capacity as a temporary lieutenant, was in charge of a landing craft that arrived on the Sicilian shore an hour early. When asked disparagingly by a comrade what his peacetime career was, he responded archly: “You will allow me to point out, sir, as an actor, that in the West End of London, if the curtain is advertised as going up at 8pm, it goes up at 8pm and not an hour later, something that the Royal Navy might learn from.”

In the West End, the curtain goes up at 8pm and not an hour later, something the Royal Navy might learn from.

One who wasn’t so lucky was Kirk Douglas. The legend born Issur Danielovitch (who changed his name, having grown up as Izzy Demsky, just before he joined the U.S. Navy in 1941) trained as a communications officer before being assigned to a submarine chaser and sent to the Pacific. He suffered abdominal injuries when a fellow crew member mistakenly launched a live ash can instead of a depth charge marker during a pursuit of a Japanese submarine. Doctors at Balboa hospital in San Diego, where he was sent, also discovered he had chronic amoebic dysentery, and he was discharged having attained the rank of lieutenant junior grade.

If all of the above can testify to the physical horrors of war, the Miami-born, Bahamian-raised actor Sidney Poitier had first-hand experience of the psychological ravages. The star of Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), having lied about his age to participate in the war effort, was assigned to a Veterans’ Administration hospital for shellshocked veterans on Long Island. He eventually feigned mental illness himself to get a discharge. “We would in time become no more than jailers,” he wrote in his memoirs. “The army was not heavily into the mental health business.”

It would be remiss not to mention, as well as the leading men who went straight to the coalface during the most destructive global conflict in history, the leading women who did far more than maintain the troops’ morale between battles (although Bette Davis, Rita Hayworth, Judy Garland and Lauren Bacall were all deployed in such a capacity). One of the most arresting stories in the canon is that of one of the most celebrated leading women of all time.

Born in 1929, Audrey Hepburn — whose estranged British father was a Nazi sympathiser — was living a life of penury in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands when war broke out. Having honed her skills as a ballerina for nearly four years at the Arnhem city theatre, she was enlisted by the Resistance leader Dr. Hendrik Visser ’t Hooft to take part in illicit musical

performances, with theatre windows blacked out, which raised funds to help shelter Jews and other repressed individuals hiding across the country.

Hepburn wasn’t alone as a woman who contributed more than glamour to young men on the frontline. Marilyn Monroe — who went on to do precisely that, famously, in the Korean war — worked in an aircraft factory assembling drones and spraying fire retardant onto planes during world war II (leading to her discovery by an army photographer); Bette Davis carried out promotional work for the Red Cross (as well as carrying out morale-boosting performances); and Marlene Dietrich, the first German actress to conquer Hollywood, recorded anti-Nazi material in her native tongue for the Office of Strategic Services.

It seems appropriate to conclude this chronicle, though, with a nod to another man: the one Tinseltown legend to have seen action in world war II who — following Kirk Douglas’s demise at the remarkable age of 103 in 2020 — is still with us. Drafted in 1944, at the age of 18, Mel Brooks, in his capacity as a combat engineer clearing minefields and building bridges for the 1104th Combat Engineer battalion, was a major protagonist in clearing the path for the Allied advance into Germany in March (how brilliantly ironic that one of Brooks’s funniest contributions to the comedy canon is Springtime for Hitler, his metafictional masterpiece in the 1967 classic The Producers).

There’s something very levelling about Hollywood actors — exalted above us mere mortals since Florence Lawrence, star of 250 silent films, became the first actor to have her name used to publicise her work in about 1910 — entering the bloody fray alongside the anonymous hoi polloi. There’s also something very galvanising, and timely to reflect on, about the spirit of mass international co- operation — the sentiment geared towards the greater good — with which they were motivated. We can only surmise how impressed Roosevelt was.

Photo credits: Getty Images