Who is the Rake: Douglas Bader

He was a double-amputee fighter pilot whose legendary sorties in world war II turned him into a rather old-school national hero. One thing is for sure: we will not see the likes of Douglas Robert Steuart Bader again.

On December 14, 1931, at Woodley airfield near Reading, RAF pilot officer Douglas Bader was, in his own words, “ragging about a bit”, indulging in some low- level aerobatics in a Bristol Bulldog mark IIA single-seat biplane. Bader had already courted expulsion from the service with a high dangerous and/or illegal stunt count, and this turned out to be his reverse-Icarus moment: the tip of his left wing clipped the ground, the plane somersaulted and crashed, and he was rushed to the Royal Berkshire Hospital, where both his ruinously injured legs were amputated, one above and one below the knee. This was how he chose to record the life-changing moment in his logbook:

“Crashed slow-rolling near ground. Bad show.”

The almost pathological breeziness is Bader to a tee — here was someone who never made a show, good or bad, of his emotions — but his extraordinary reserves of grit and determination have to be inferred. By April 1932 he was walking again on prosthetic limbs, eschewing sticks and crutches — “I was told I’d be all right with them, but I said I’d rather be all right without them... one gets tangled up in them” — and by the end of world war II he’d been enshrined as a bonafide flying ace, with 22 aerial victories and a string of other combat citations to his name.

Decorated (with a C.B.E., a D.S.O. & Bar, and a D.F.C. & Bar) and immortalised in a bestselling biography by Paul Brickhill called Reach for the Sky, later made into a film with Kenneth More as Bader (“This is a story of courage... the courage of a man’s refusal to accept defeat... when defeat seemed inevitable,” blared the film’s trailer), he became a sort of paragon of pluck. You can practically smell the pipe smoke emanating from the radio during his Desert Island Discs appearance in 1981, when, his speech littered with “old boys” and “marvellous chaps”, he forswears the likes of Beethoven (“and his 95th sonata, or whatever it is”) in favour of the more prosaic charms of Flanagan and Allen and Val Doonican. For good measure, his luxury item is a sand iron and a set of golf balls.

But for all the clubbability, there was always a rich seam of nonconformism in Douglas Robert Steuart Bader. He was born in 1910 in St John’s Wood, the second son of Major Frederick Roberts Bader, a civil engineer on temporary furlough from his India posting, and Jessie MacKenzie, 20 years the major’s junior, an exiled Aberdonian who’d been brought up in Kotri, in what is now Pakistan. According to Brickhill’s biography, the family G.P. announced Bader’s birth with the words, “The little troublemaker has arrived”, and, noting his persistent squeal, added prophetically that he seemed to have a talent for expressing himself forcibly.

Bader’s childhood was coloured by the early death of his father, after the major was wounded in action during world war I; there were tussles with his mild-mannered stepfather, the Reverend Ernest William Hobbs; an unfortunate penchant for firing air rifles at nonplussed bystanders (including his own brother, Derick, shot in the shoulder at point-blank range); and less-than-stellar academic application. “I got a zero for maths,” Bader would later cheerfully apprise an interviewer, “but I was quite good at games”, downplaying his aptitude (and competitive zeal) for rugby, cricket and, later, golf.

His peers took note of his puckish demeanour, all high forehead, rolling dark curls and jutting chin.

Not for the first time, the armed services offered a haven for a slightly wayward spirit with excessive energy to burn. Bader’s uncle, Cyril Burge, was a flight lieutenant at RAF Cranwell, to which Bader won a coveted prize cadetship in 1928. That same year, he took his first flight with his instructor, the cherishably named Flying Officer W.J. ‘Pissy’ Pearson, in an Avro 504, and was commissioned as a pilot officer into No.23 Squadron RAF based at Kenley in Surrey in 1930. His peers quickly took note of his puckish demeanour (all high forehead, rolling dark curls and jutting chin) and forceful personality — “Woe betide any young cock who thought he might share the roost,” was the verdict of fellow pilot Pete Tunstall, later a P.O.W. alongside Bader in Colditz prison — and, while no one was shocked when he came a cropper in his Bristol Bulldog, they were taken aback by his savoir faire in the face of the most daunting adversity — offered a glass of brandy when being stretchered away from his burning hulk, Bader replied evenly, “No, thanks very much, I don’t drink” — and the gusto with which he rebuilt his life, adapting to prosthetics that were a far cry from today’s lightweight blades, returning to sports, cutting a rug on the dancefloor, and taking country drives in a specially converted MG and, later, a series of Alvis drophead coupés. It was during a tool down the A30 in one of the latter that Bader stopped at a tearoom called the Pantiles; the waitress who served him, Thelma Edwards, would become his devoted wife.

Forcibly invalided out of the RAF, Bader went to work for the aviation section of the Asiatic Petroleum Company, later to become Shell — “we used aeroplanes for exploration,” he recalled; “after all, there were no roads in the likes of Borneo at that time” — but worked his Cranwell connections to rejoin the service at the outbreak of world war II. Lingering scepticism among the top brass at Bader’s suitability for the rigours of fighter-piloting — and the fact that, at 29, he was considerably older than his fellows — was quickly dashed when he demonstrated his facility with a Spitfire (“the aeroplane of one’s dreams,” was his verdict, “and luckily they had handbrakes, not footbrakes”) and by the unexpected advantage for Bader that the high G-force experienced in combat manoeuvres, which caused other pilots to pass out as the blood drained from their brains into their legs, didn’t apply to him. He was posted to Duxford and scored his first victory in 1940, downing a Messerschmitt-109 while patrolling the coast near Dunkirk. He went on to assume effective command of a series of squadrons during the Battle of Britain, and became one of the first ‘wing leaders’ at Tangmere in West Sussex, where he was instrumental in developing the ‘big wing’ tactic — assembling large formations of defensive fighters poised to inflict maximum damage on the massed German bomber formations as they flew over south-east England. He led from the front, cracking hoary jokes, swearing effusively, chuffing doggedly on his pipe, revelling in his callsign, ‘Dogsbody’ (from the D.B. initials that adorned his Spitfire), and dubbing his wing the Green Line Bus (motto: ‘Return tickets only’). He was lauded despite his reflexive irascibility in the face of officialdom — “His tenacity made him a truly national hero in every sense,” said Air Chief Marshal Sir Michael Beetham, of Bomber Command — and his seeming invincibility through endless sorties became legendary.

Bader rode his luck until August 1941, when, rammed by a Messerschmitt-109, he was forced to ‘take to the silk’ over northern France, injuring his ribs and mislaying one of his legs in the process. After treatment at a hospital in Saint-Omer (the same one in which his father had died decades before), he was invited to visit Lieutenant-Colonel Adolf Galland, commander of the nearby Luftwaffe airfield at Wissant. The Germans, aware of his reputation, treated him cordially, allowing him to sit in the cockpit of a Messerschmitt, if not, as he requested, to take it “for a spin”, and arranging for his errant leg to be air-dropped by the RAF. He repaid their courtesies by becoming a serial escapee, shinning down from a third-floor hospital window in a string of knotted bedsheets and breaking through perimeter fences so often that his captors squirrelled his legs away at night.

He rode his luck until he was forced to ‘take to the silk’ over northern France, mislaying one of his prosthetic legs.

Eventually he was shipped off to the austere Colditz Castle in Saxony, which, like a Stalag Trip Advisor, he described as “far and away the best camp in Germany”, principally because of its international cast: “There were Dutch, Poles, Belgians, Czechs, French and British, and we made it our policy to constantly harass the enemy.” The guards may well have heaved a sigh of relief when the camp was liberated by U.S. troops in April 1945.

Bader returned home the Biggles-esque poster boy for RAF derring-do, leading a thunderous victory fly-by over London in his ‘Dogsbody’ Spitfire and revelling in the success of Reach for the Sky, though he was at pains to point out that, “I shouldn’t be mistaken for the nice, dashing man that [Kenneth] More was”. Indeed, tact and diplomacy were never his strong suits — “My God, I had no idea we left so many of you bastards alive,” he cried on walking into a reunion of former Luftwaffe pilots arranged by his old frenemy General Galland — and calls for him to become an M.P. were quickly muted when he disclosed a set of trenchant opinions — on apartheid, capital punishment and immigration — that made the likes of Enoch Powell look moderate.

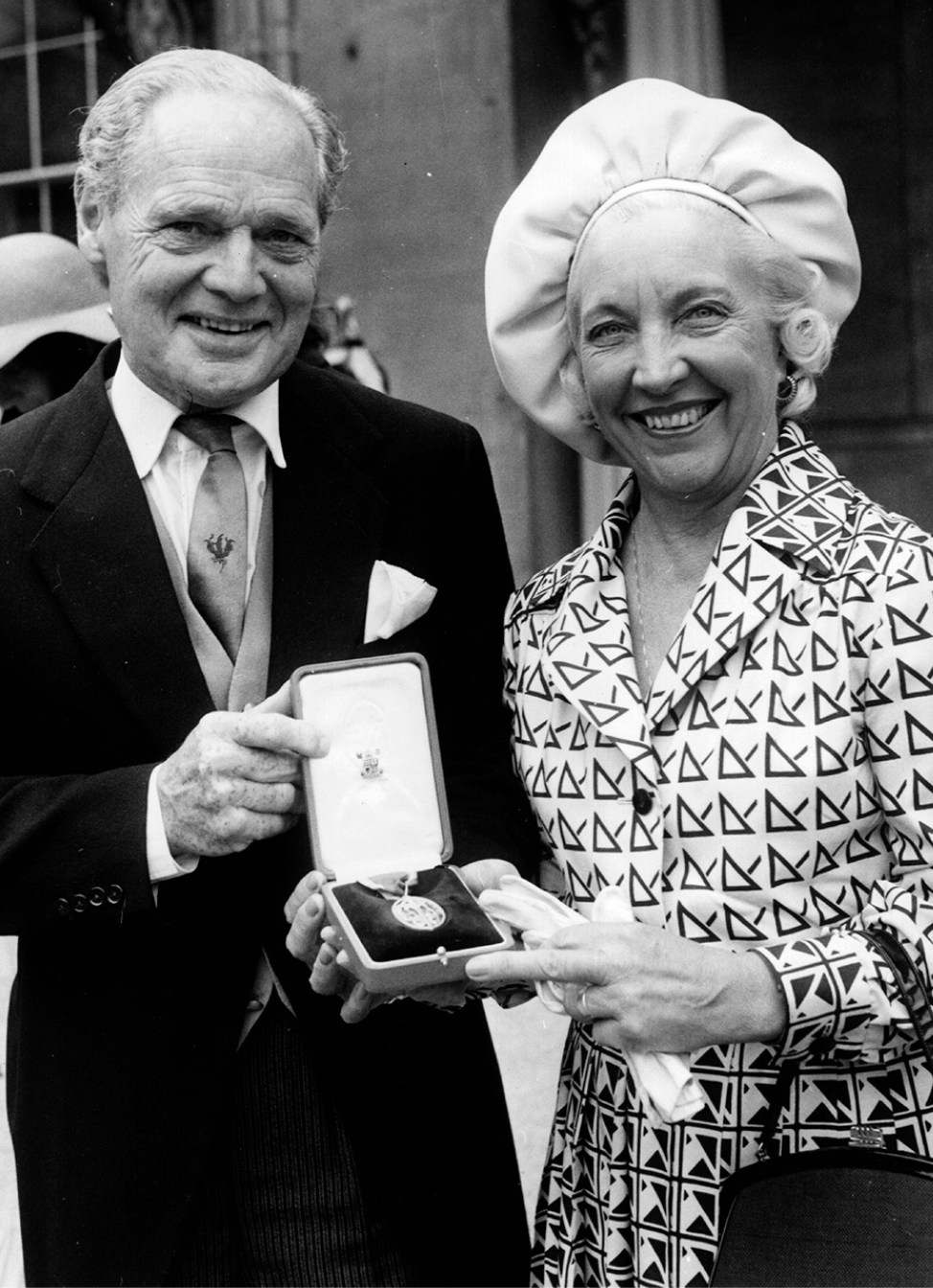

Instead he returned to duty with Shell, continued to pilot, now favouring Percival Proctors and Beechcraft Bonanzas — he would eventually log a total of 5,744 hours of flying time — and advocated for amputees, wounded veterans and disabled children, for which he was knighted in 1976. Bader’s heart finally gave out six years later, after he attended a dinner honouring the 90th birthday of Sir Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, but by then his triumph-over-tragedy story arc was imperishable. Not that Bader would have ever bought into a Hollywood ending for himself. “I just made a balls of it, old boy,” he would say, when people had the temerity, on reviewing his life, to throw words like ‘gumption’, ‘spunk’ and ‘mettle’ in his direction. “That’s all there was to it.”

Bader returned home the Biggles-esque poster boy for derring-do, leading a victory fly-by over London.

Photo credits: Getty Images