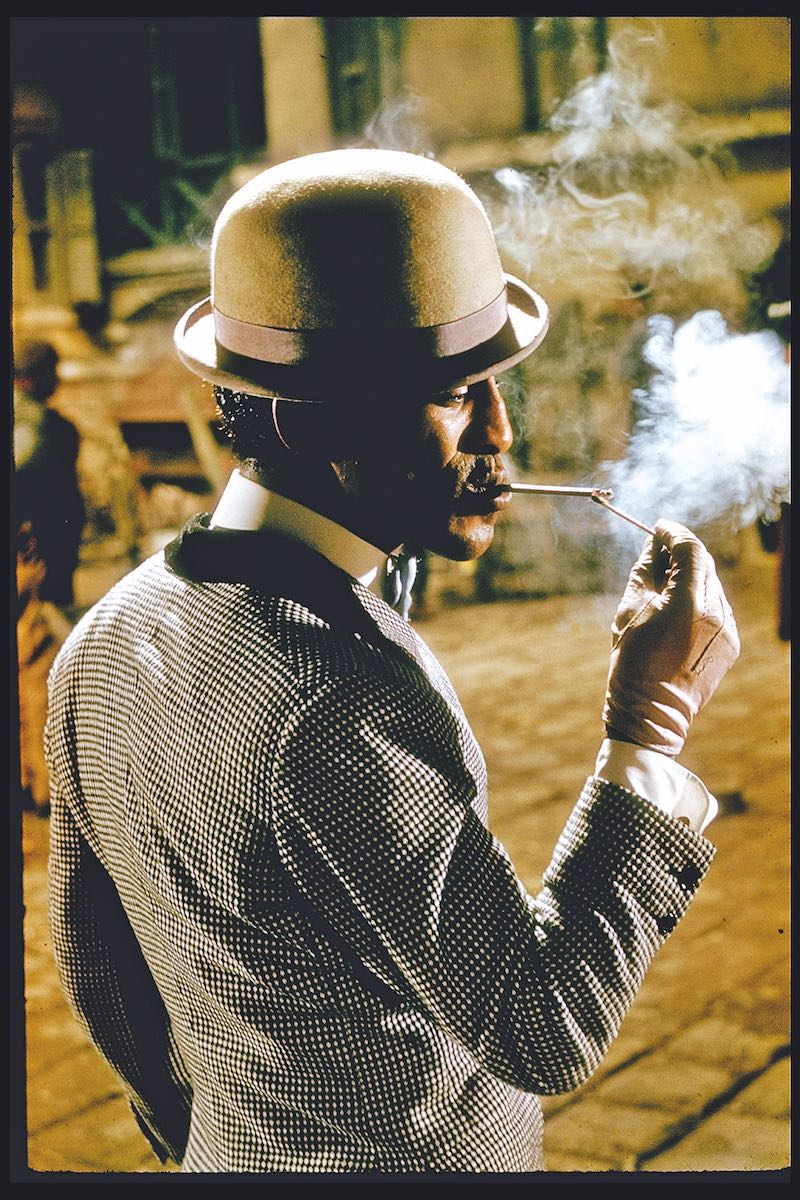

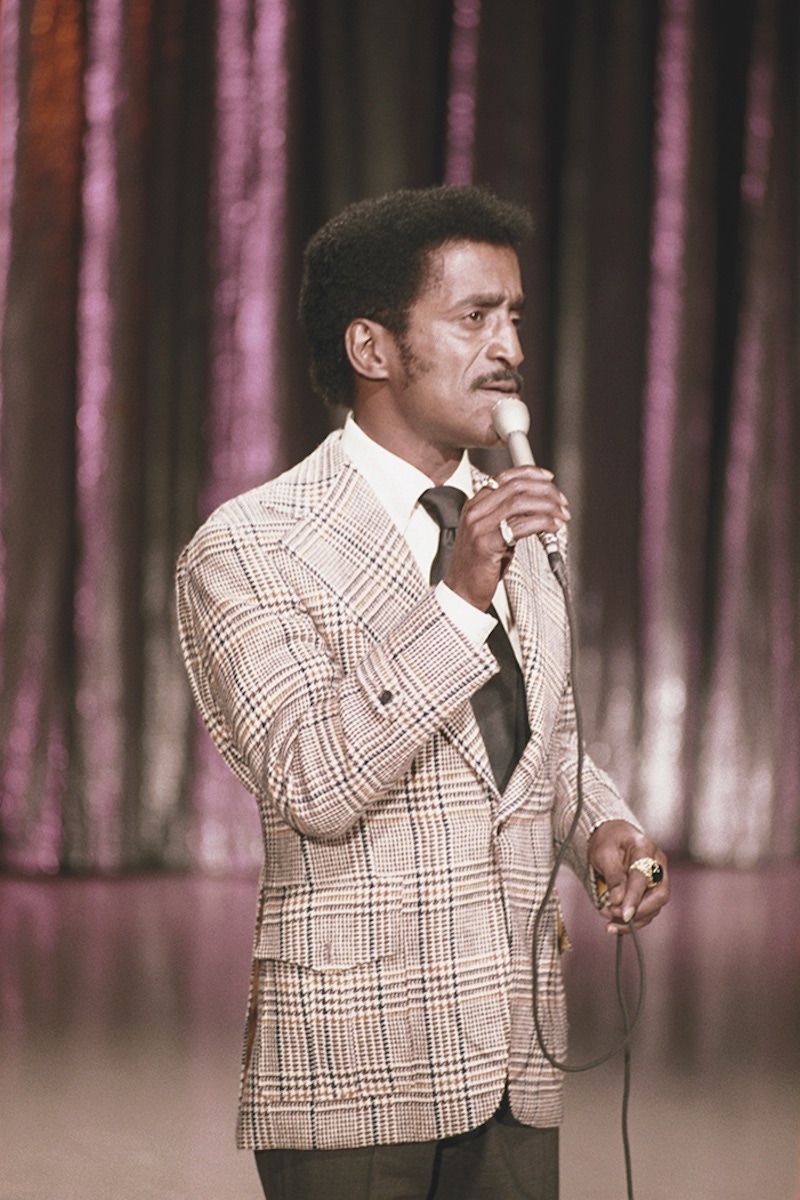

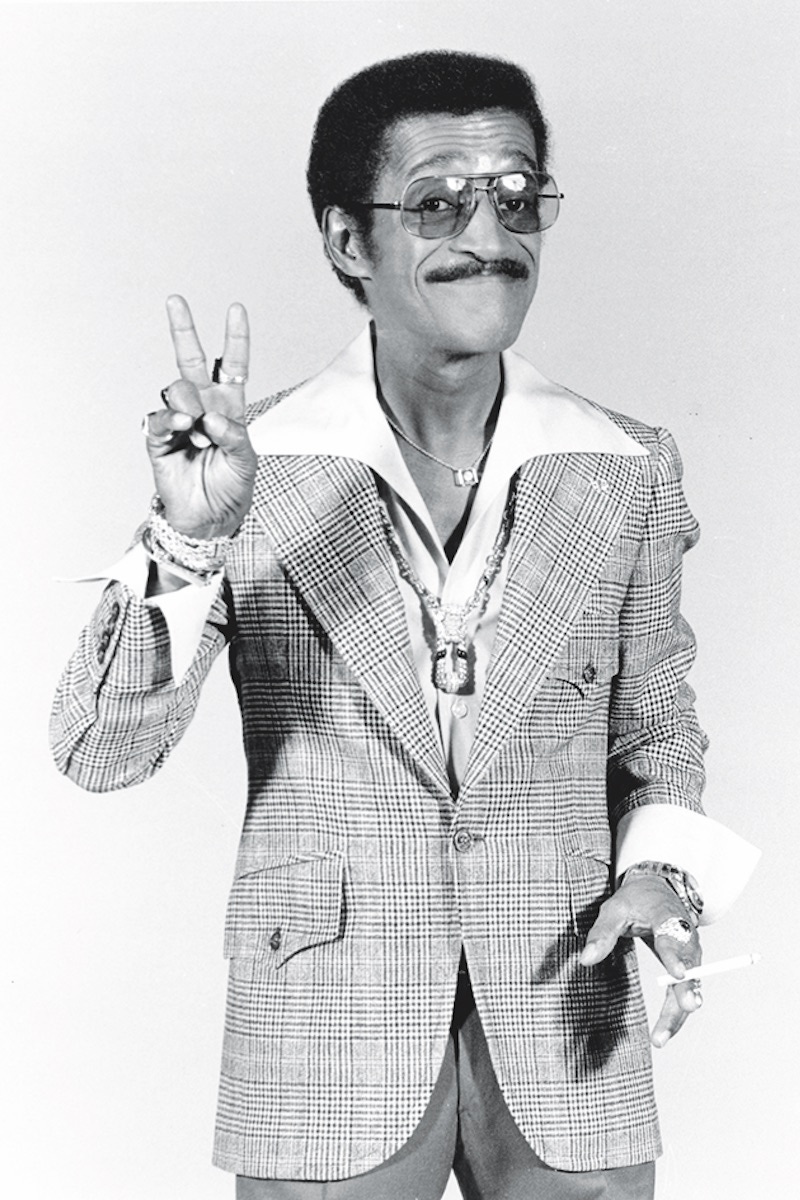

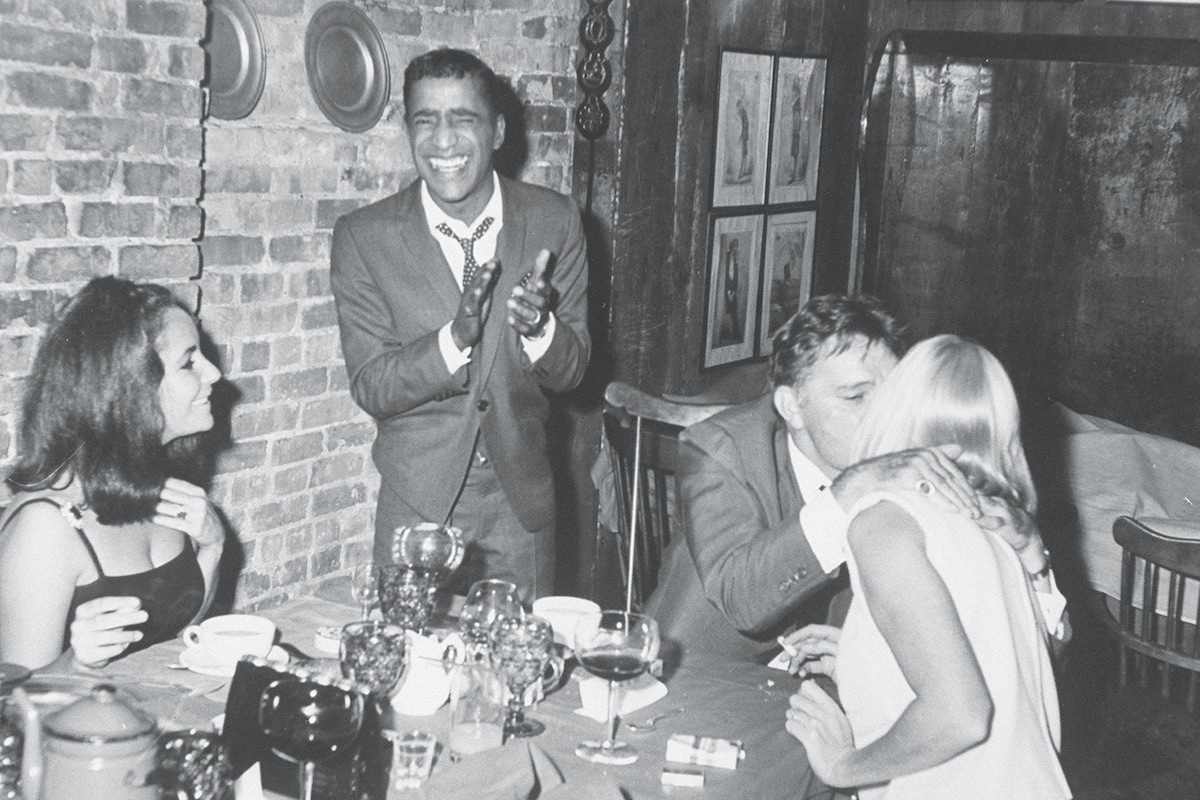

A GIFT FROM A GENEROUS GOD: Sammy Davis Jr.

Some people wanted Sammy Davis Jr. to fight; some wanted him to make peace. Such was the invidious position ‘Mr. Show Business’ found himself in as mid-century America wrestled with its race issues. ‘I didn’t ask to be a trailblazer,’ Davis Jr. said. ‘My passion was to entertain.’

One night in the mid 1960s, Sammy Davis Jr. was nearing the end of a sold-out show at the Chi Chi nightclub in Palm Springs. He wound up a song and embarked on a Jerry Lewis impression while soft-shoe-shuffling his way offstage. In a holster on his right thigh was a .45 calibre pistol, loaded with blanks; Sammy was one of the fastest draws in Hollywood, and a quick pull-and-fire often served as an explosive finale to his act. Due to some oversight, however, the pistol was, on this particular night, already cocked. As he reached to pull it, the powder from the blank shot through the holster and onto his mohair tuxedo pants. Smoke started rising, and a circle of skin on his calf began to burn. Some members of the audience screamed; Sammy continued to dance while muttering to a stagehand, “Go get a doctor”. He was still mugging into the wings, even as the front rows caught the whiff of singed flesh. For Davis Jr., the show — which often ran to a Springsteen-esque three and a half hours, and encompassed tap-dancing and trumpet playing alongside the crooning and comic riffs — had to go on. He once told an interviewer: “This is what I want on my tombstone: ‘Sammy Davis Jr., the date, and underneath, one word — entertainer’. That’s all, because that’s what I am, man.”

His peers would have appended ‘consummate’. “He was the best of us, no question,” said Frank Sinatra, Davis’s Rat Pack confrère and friend of four decades. “It was a generous God who gave him to us.” For decades, the short (he admitted to five-foot-six), slim (28-inch waist) showman with a broken nose, recalcitrant jaw and loopy, winning smile had energised stages from Borscht Belt cabarets to royal variety performances with his rakish charm and feline grace. So why did he feel the need to carry a gun, along with an umbrella that had a knife concealed in its tip?

The answer is bound up with the vexed state of American race relations during Davis’s era: he was often the only person of colour in the room (a room, furthermore, that would have barred him if he hadn’t been the headliner), and who relied on white patronage, principally that of Sinatra, to open doors for him. His conversion to Judaism and marriage to a Swedish actress made him a lightning rod for white anger and black consternation, something he acknowledged with mordant humour in an interview with Playboy magazine, where he noted that his mother was Puerto Rican. “So I’m Puerto Rican, coloured, Jewish, and married to a white woman,” he said. “When I move into a neighbourhood, people start running four ways at the same time.”

In the face of such adversity, Davis liked to say, “talent was my most effective weapon”. He was born in the winter of 1925 in a Harlem tenement; his father was lead dancer and his mother, Elvera, was in the chorus of a vaudeville troupe headed by his adopted uncle, Will Mastin. Davis made his stage debut aged three, and skipped formal education entirely to tour with the Will Mastin Trio after his parents divorced and his father gained custody. At 17 he was drafted into the U.S. Army’s first integrated unit, where he was beaten — including having his nose involuntarily remodelled — and humiliated by white enlistees, until a sergeant named Williams intervened, taking Davis in hand and teaching him to read and write. “He distracted me from all my rage, all my anger,” Davis said in a book by his daughter Tracey, Sammy Davis Jr.: A Personal History with My Father. “With all that I endured, I never turned round and hated right back. There was always some white guy like Sergeant Williams or Frank Sinatra who helped me back up.”

Read the full story in Issue 71 of The Rake - on newsstands now.

Available to buy immediately now on TheRake.com as single issue, 12 month sub or 24 month sub.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine

Subscribe and buy single issues here.