A Peerless Peer: Lord Snowdon

What makes a great man? What might ruin a reputation? Lord Snowdon married up, and his private life was often messy, but did Britain’s bourgeois mumblings mean his accomplishments were overlooked?

Posthumous reputations are seldom unequivocally fair. Some take an embarrassment of achievements to the grave and are then recognised for a single contribution to posterity (Nicolaus Copernicus enriched our understanding of the cosmos in uncountable ways, but is remembered solely for the heliocentric model of the solar system); others achieve next to nothing but enjoy eternal recognition for a single act (in some cases a single act they didn’t even carry out: Amerigo Vespucci — the obscure navigator after whom, by many accounts due to a blunder by an early cartographer, the most powerful nation in the world is named — springs to mind).

Still more have manifold achievements overshadowed by a single transgression or foible: during Bill Clinton’s tenure in the White House, 1,700 Soviet nuclear warheads were dismantled while America reached its lowest poverty rate in 20 years and paid off $360bn of the national debt. Yet how many students of history in decades to come will find themselves flicking through the glossary sections of the vast tomes dedicated to the 42nd Potus seeking out the word ‘cigar’?

It is also sad, given his considerable contributions to humanity, that Antony Charles Robert Armstrong-Jones is largely remembered as the plebeian who married a princess, a marriage that, as outlined in an unofficial 2008 biography by Anne de Courcy, eventually involved separate rooms within Kensington Palace and more than a little spicy extracurricular on the part of both parties.

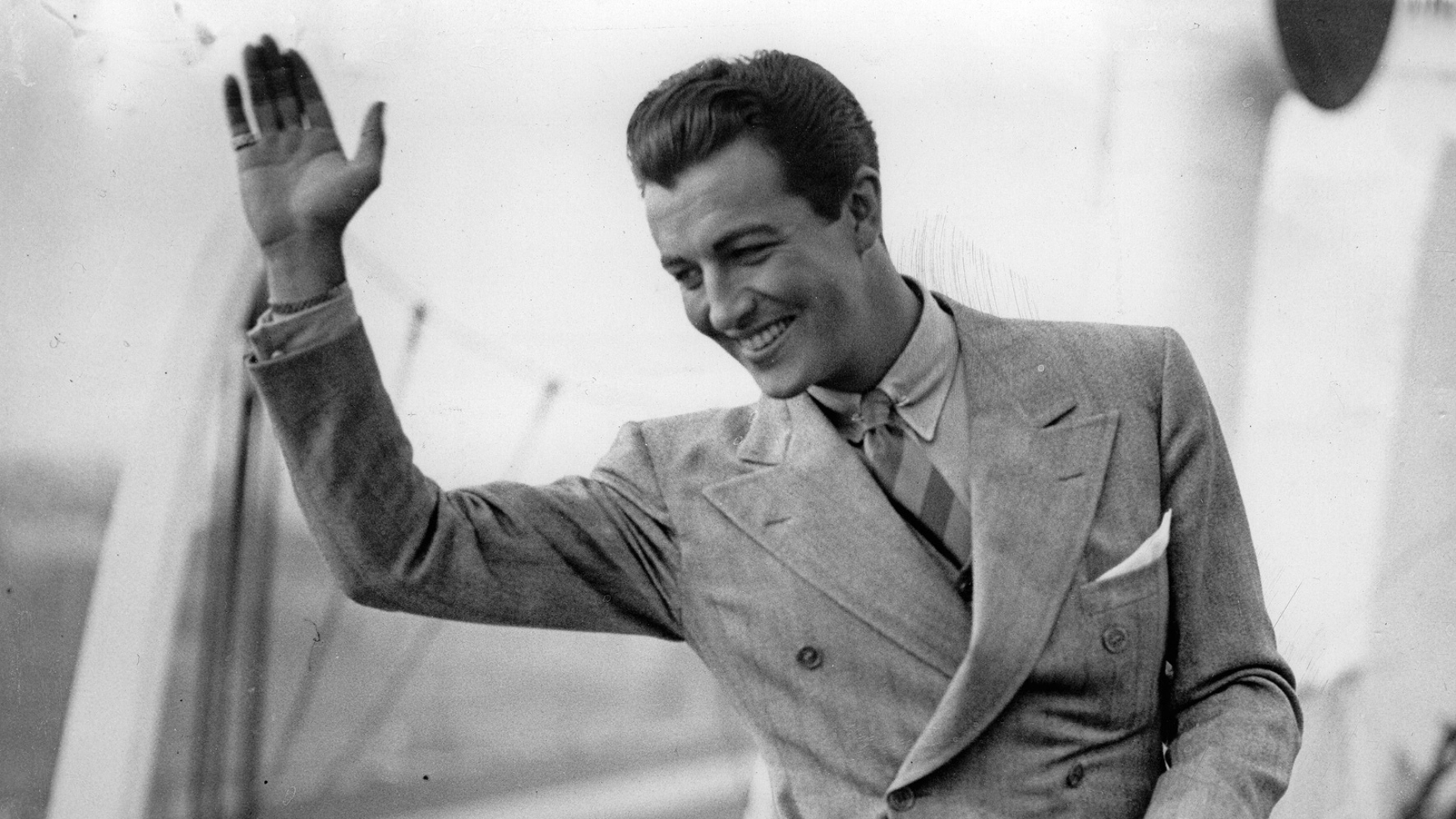

My use of the word ‘plebeian’ is only really valid because it was a marriage to the Queen’s sister we’re talking about. Born in London in 1930 into Welsh gentry — his father a barrister, his mother a society figure — Tony, as he was known to his nearest and dearest, was (literally) born into a house, in Belgravia’s Eaton Terrace, that was a wedding gift from his maternal grandfather. Oliver Messel, the theatre designer, was a maternal uncle, and the Victorian artist and cartoonist Linley Sambourne was an ancestor.

His sister was his only hospital visitor during his struggle with polio, which would leave him with a permanent limp.

The childhood of a man who would become the 1st Earl of Snowdon — when, in 1960 at Westminster Abbey, the nuptials were read for him and Princess Margaret (the youngest daughter of King George VI) — was anything but charmed. He was whisked between feuding parents, who separated when he was three, and he was treated as inferior in the new household created when his mother went to Ireland and married the Earl of Rosse, as was his sister, Susan, who was also his only hospital visitor during his struggle with polio in his teens, which would leave him with a permanent limp and return to trouble him as an older man.

Indeed, the phrase ‘formative years’ is a poignant one in the case of Lord Snowdon. It seems reasonable to speculate that it was his lonely childhood that prompted him to adopt solitary hobbies. One was gadgets: the aforementioned Oliver Messel, something of a mentor to the young Tony, helped him, when he was six, create a functioning toy submarine; his later design feats included an electric toaster (a crucial boarding school accessory at 13); and, following the bout of polio, a radio and a wheeled platform to convert ordinary chairs into wheelchairs (which was exhibited at the London Design Festival in 2003) as well as aids for the deaf and blind.

It was this penchant for gadgetry that led him to cameras, and eventually a creative oeuvre for which he really ought to be more celebrated. Taking up photography having abandoned his studies at Cambridge (where he had already switched from natural history to architecture just 10 days in), his work following an apprentice under the court photographer known as Baron was celebrated for freshening up royal portraiture with an informal, invigorated approach enabled by his partial insider status.

He also worked with subjects from the theatre, dispensing with starchy on-stage poses and instead, in deference to the kitchen- sink genre popular at the time, snapping them on the streets — in situ, as ordinary humans. He was fond of surprises — sometimes with a splash of colour within his frame, other times with his photograph’s entire message (he once shot Germaine Greer and Plácido Domingo on a single motorcycle; notably, the celebrated Spanish opera singer is riding pillion, not the feminist).

View his work in the context of his game-changing approach, and it’s little wonder it was exhibited throughout the world and showcased in about 20 tomes. Unsurprisingly, images of his wife of 18 years and one in particular of Diana, Princess of Wales — in a chiffon blouse by Emanuel, commissioned by Vogue shortly after Diana’s engagement was announced — are among his most popular works.

When it came to pictures of the moving variety, the 1968 documentary he made with his friend Derek Hart, Don’t Count the Candles — an emotive piece about ageing — won two Emmys, the St. George prize at Venice, and gongs at film festivals in Prague and Barcelona. And his creative endeavours didn’t begin and end with capturing life through a lens: a consultant with the Council of Industrial Design, Snowdon also devised Britain’s first walk-through aviary — a 24-metre-tall icon, intended (rather like the Eiffel Tower) to be only a temporary structure but which has just been re-christened Monkey Valley more than 60 years later. He was a provost of the Royal College of Art for eight years from the mid 1990s, and he also threw his weight behind causes including the Welsh National Rowing Club, the Civic Trust for Wales, and Rotary International’s worldwide campaign against polio.

Snowdon’s tireless campaigning for the disabled saw him take the cause to the House of Lords, having kept the title the Queen bestowed on him the year after his marriage. “It’s not that one is making a special case of disabled people,” he once said. “It’s just trying to ensure that they enjoy some of the same rights as the able- bodied.” It’s a sentiment that explains his work; disparate groups including British Rail, Butlin’s holiday camps and the Church of England were all on the receiving end of his righteous ire. In 1980 he set up the Snowdon Award Scheme (now the Snowdon Trust) to help disabled students in further education.

Also noted by those who knew him best was Lord Snowdon’s gracious behaviour in the wake of his divorce from Princess Margaret in 1978. One broadsheet obituary compared his conduct favourably to the “unseemly behaviour of a later generation of royal divorcés”.

His dignity and social standing remained impervious to the salacious efforts of the British press machine.

Indeed, his unassuming, turtleneck-wearing charm having long since won over the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh, he maintained an affable relationship with the royal family, even appearing with his estranged spouse at the Queen’s 50th birthday party and, later, refusing to talk about the monarchy as a former insider when doing so could have drawn lucrative attention to global book tours.

His dignity and social standing seemed to remain impervious to the salacious efforts of a British press machine that purred with ill-disguised glee as it delved into his protracted affair with Lady Jacqueline Rufus Isaacs; another with the journalist Ann Hills, who killed

herself in 1997; and with the mental health campaigner Marjorie Wallace. He had already had a daughter, Polly Fry, born during the third week of his honeymoon with Princess Margaret.

It’s a fact of life that prolific extramarital endeavours will see the word ‘notorious’ added to the legacies of people who have done so much good, conducted themselves with dignity and benevolence, and are — by nature, by nurture, or some combination of both — thoroughly decent. Which is particularly regrettable, as being a bit of a player, so to speak, is so often the sole shortcoming of otherwise unerringly wholesome individuals.

As such, we implore that even he who is without sin to cast no stone, because Lord Snowdon’s was a life that reminds us to put our primness aside when evaluating a person’s worth and contribution to the great tapestry of life.

Photo Credits: Getty Images