America's Godfather: Robert De Niro

Ed Cripps delves into the moments the Godfather star shone brightest, from speaking out recently about America's presidential candidates to his silver screen success.

In 2016, Robert De Niro said of presidential candidate Donald Trump: “He’s so blatantly stupid. He’s a punk. He’s a dog. He’s a pig. He’s a con, a bullshit artist, a mutt who doesn’t know what he’s talking about, who doesn’t do his homework, doesn’t care, who’s gaming society, doesn’t pay his taxes. He’s an idiot. Colin Powell said it best: he’s a national disaster, an embarrassment to this country. It makes me so angry that this country has got to this point that this fool, this bozo has wound up where he has. He talks about how he wants to punch people in the face… Well, I’d like to punch him in the face.” The video was considered too partisan to form part of the official #VoteYourFuture initiative for which it was recorded, but it was released separately and captures the De Niro ethos perfectly: timely, serious, direct, uncowed, emotionally intelligent, anti-establishment, virile, clear, rhythmic, politically conscious, legitimate fury. His voice-of-the-people soliloquies still beguile and this latest monologue rhymes, somehow, with Travis Bickle’s “You talkin’ to me?”

He may have inherited this counter-culture eloquence from his New York artist parents: his mother wrote erotica for Anais Nin, while his father Robert De Niro Sr painted in the same expressionist circles as the de Koonings. They divorced when his father came out as gay and remained friends: the actor has since made a poignant HBO documentary about his dad, whose art never received the recognition he felt it deserved (during an interview with Out Magazine, the actor cried at the idea he’d become more famous than the person he was named after). Mentored by the august acting coach Stella Adler, who said he was the best student she ever taught, De Niro Jr caught the eye as a dying baseball player in Bang The Drum Slowly (to this day one of Al Pacino’s favourite films) and as swaggering, Rolling Stones-voltaged Johnny in Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets. “This kid doesn’t just act – he takes off into the vapors,’’ wrote Pauline Kael in The New York Times.

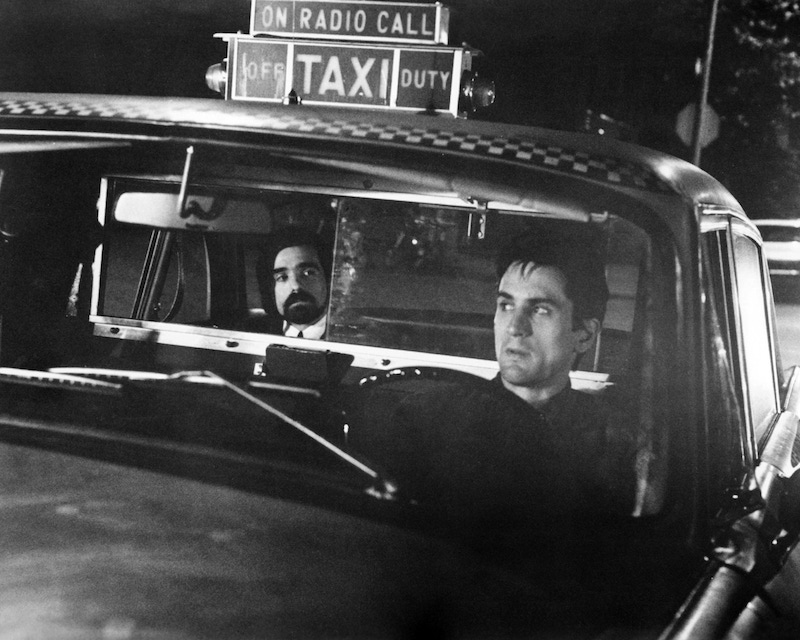

De Niro’s audition for the role of Sonny Corleone (since made public and described by Francis Ford Coppola as “spectacular”, but “too killer”) conjures up a fascinating alternative Godfather universe. Instead, he was cast as the young Vito Corleone, for which he lived in Sicily to pick up the dialect and won his first Oscar. With only eight words of English, it is a riveting performance: grand-canvas, measured and violently humane. Comparisons to Brando were immediate and Marlon himself even said, “I doubt if he knows how good he is”. De Niro's famously exact role-research (he worked as a cabbie for Taxi Driver and could have boxed professionally by the end of his regime for Raging Bull) has created some of the most relatable rebels in the history of cinema, a vanity-free perfectionism that De Niro describes as a "mixture of anarchy and discipline". Only he, as Travis Bickle, could have captured the full fall from nervy romcom-sweetness to the sort of dream-tense nihilism that would inspire a fanatic who'd seen the film 15 times to try to kill Ronald Reagan.

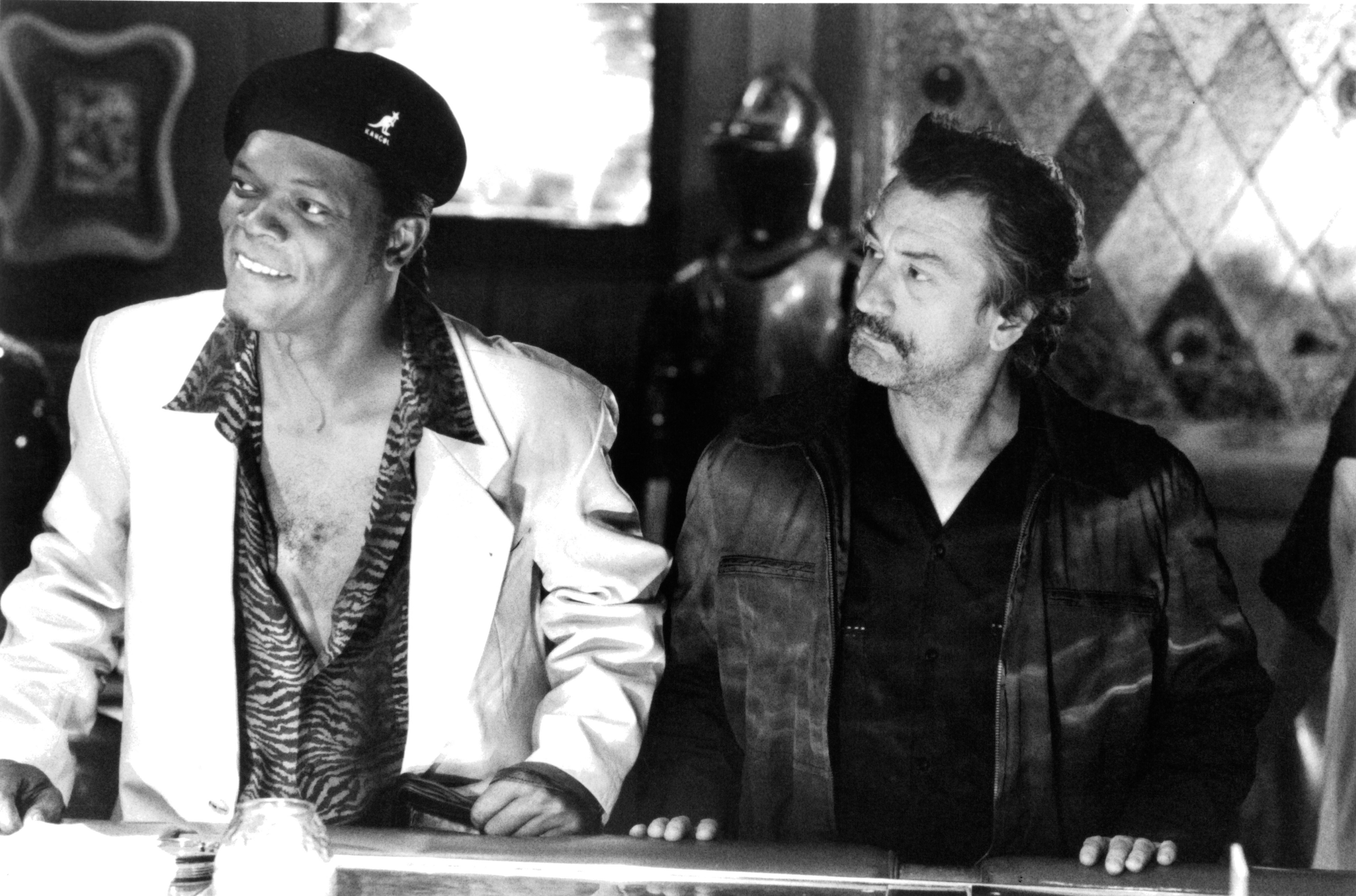

Constellations emerge in the solar system of the De Niro canon, especially violence as a career (The Deer Hunter, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, Once Upon A Time In America and as Al Capone in The Untouchables, whose director Brian De Palma described De Niro as a “goddam chameleon”) and fame-troubled loneliness (Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver and Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy, his most underrated film). He gravitated towards risk-taking auteurs (Bertolucci on 1900, Elia Kazan on The Last Tycoon, Terry Gilliam on Brazil, Quentin Tarantino on Jackie Brown) and, though in 200 he played the wiseguy persona in a more comic key (Analyze This, Meet The Parents), he has done thoughtful work with David O. Russell on Silver Linings Playbook, directed CIA origin-story The Good Shepherd (a fascinating riff, in light of his own life, on secrecy).

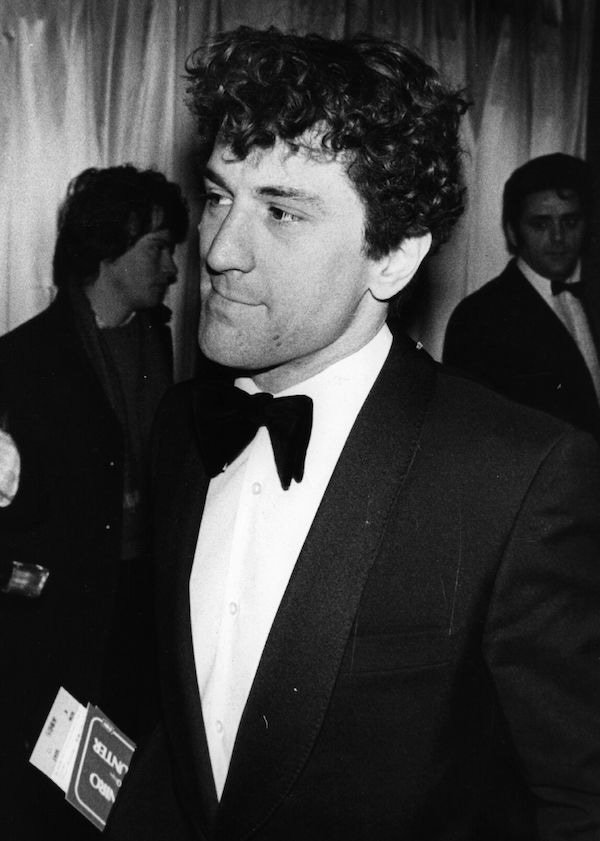

Off-screen, De Niro is an interview-wary enigma. Billy Bob Thornton once said: “With every other actor, I kind of know what they'd be like in real life… But with Bob De Niro I have absolutely no idea.” A 1987 Vanity Fair profile called him “The Shadow King”; a Guardian interview described him as “the Moby Dick of American acting, forceful on screen and gauzy in public; a creature of splashy arrivals and murky descents.” One summer, the young De Niro hitchhiked from Ireland to Italy to find relatives, as though his identity eluded himself as much as anyone else. This unknowability only helped his commitment to roles. A contemporary once described his vast wardrobe of disguises: “Bobby had this walk-in closet. It was like going into a costume room backstage of a theatre. He had every conceivable kind of getup imaginable—and the hats! Derbies, straw hats, caps, homburgs.”

Now and then, hedonistic glimpses flash through. He shared a love of coke with his great friend and fellow Playboy Mansion-frequenter John Belushi (De Niro had even been in Belushi’s room at the Chateau Marmont the night he overdosed). Between his two marriages, he had flings with Uma Thurman, Whitney Houston and Naomi Campbell. Combining business savvy and flawless taste, he co-founded Nobu and the TriBeca Film Festival, and owns the Greenwich Hotel and Locanda Verde. At 79 a father of six, grandfather of four, he is a lifelong Democrat who lobbied against the impeachment of Bill Clinton. De Niro's jeremiad against Trump may be the most powerful of all the celebrity detractions, given his popularity amongst people who might genuinely consider voting for him.

Some suggest De Niro’s publicity-shyness is one big method act in itself and there’s an irony, if not a surprise, that some of his most nuanced roles (Bickle, LaMotta, Pupkin) are hostages to fame, like De Niro's father, or even De Niro himself. All the same, he is a grandmaster of American cinema, equal parts chess to the art of violence, a world-class listener with a tragicomic twinkle, funnier, subtler and more versatile than some presume, refreshingly inscrutable and a quiet icon all the more potent when he raises his voice. Rupert Pupkin claims it's "better to be king for a night than a schmuck for a lifetime". After decades of artful graft and loser-cool alienation, the uniting cloth crown is De Niro’s for as long as he wants it; long may he reign.