Andy Warhol: Popping with Contradictory style

With an edge of avant-garde, Andy Warhol's largely achromatic tones were the antithesis of the Pop art movement that he erupted. It was all deliberate, but looking back he did have real style; the fashion cognoscenti of today certainly think so.

“For an artist with a lifelong reputation for sucking up to stars, Warhol also had a lifelong knack for making art that underlined their shortcomings and hollowness”, said Blake Gopnik in Warhol: A Life as Art, the acclaimed 2020 biography of the leader of the Pop art movement.

A life abounded in contradiction and ambiguity, it was these thrusts that not only fuelled his prophecy of America which was brilliantly exposed through his art, but they were present in his fashion style, and nearly every other facet of his life. Born Andrew Warhola Jr. in Pittsburgh, the decision to change his name to Andy Warhol upon his arrival in New York in 1949, unveiled early signs of his mindset of needing a public persona.

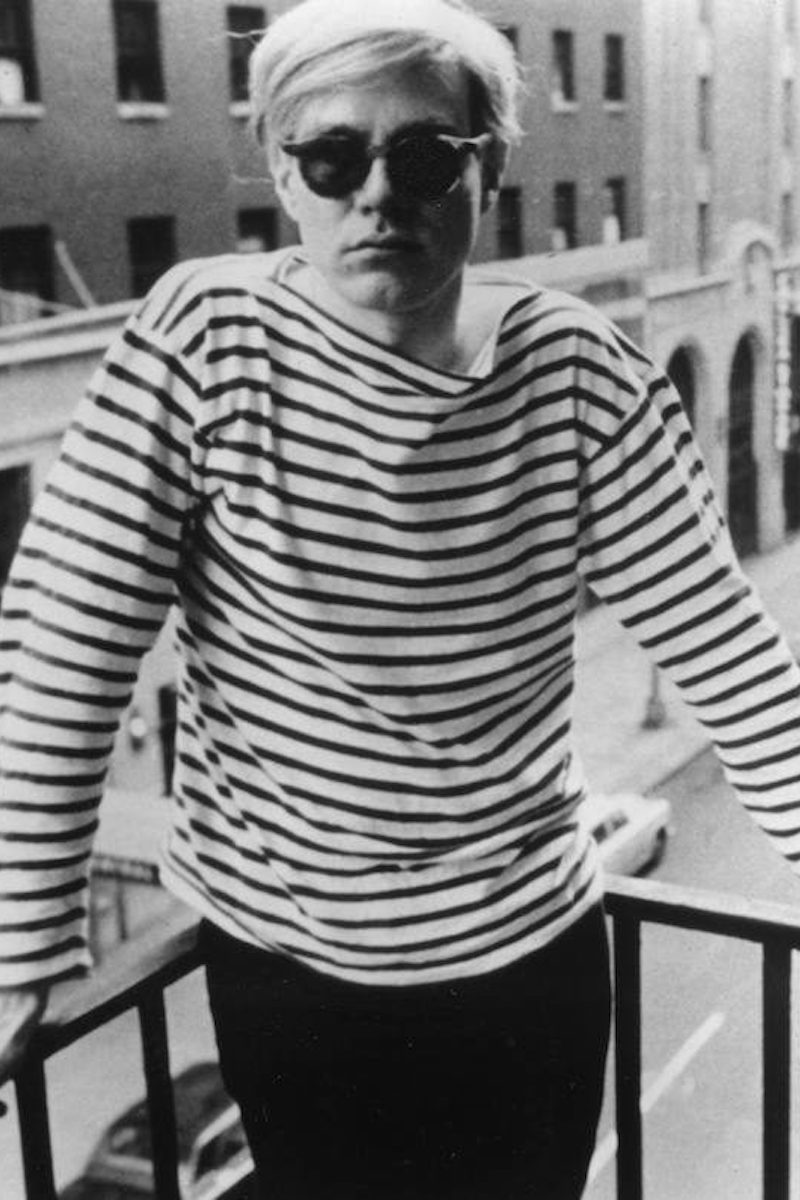

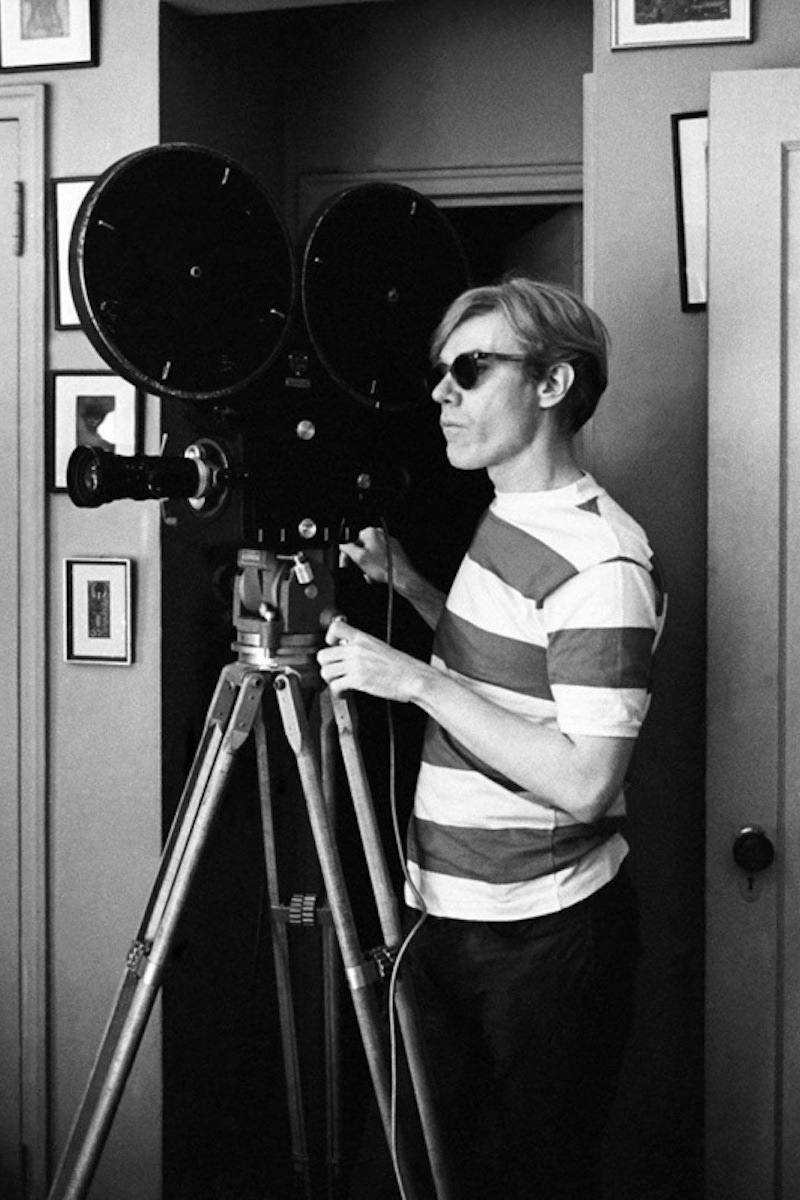

Initially dedicating himself to commercial and advertising art, his first foray into fashion came after a commission to draw shoes for Glamour magazine. Working as a shoe designer for Israel Miller, it was while in the shoe industry that his “blotted line” technique developed. London-born photographer John Coplans recalled that: “Nobody drew shoes the way Andy did. He somehow gave each shoe a temperament of its own, a sort of sly, Toulouse-Lautrec kind of sophistication, but the shape and the style came through accurately.” Like his illustrations, which featured in exhibitions at the Hugo Gallery, the Museum of Modern Art and Bodley Gallery – all in New York, the ‘50s were a time when his personal dress underwent its first real development. By wearing loose-fitting blazers, pleated trousers (probably bought from Brooks Brothers), knit-jumpers and white shirts, accessorized with a bow-tie – it reflected the preppy style of mid-century America. But with the later addition of long-sleeved Breton striped shirts and jeans, you can’t help but think it was harnessed to echo Truman Capote’s style; especially after Warhol’s onslaught of fan letters to the American novelist.

He was obsessed by Truman Capote, but Warhol observed American culture differently to anyone else. “Once you ‘got’ Pop, you could never see a sign again the same way. And once you thought Pop, you could never see America the same way again”, said Warhol. Robert Rauschenberg and Jaspar Johns were among the early artists that shaped the Pop art movement, but when Warhol showed thirty-two canvasses of Campbell’s Soup can portraits at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1962, it not only became a turning point for Warhol’s career, but was the big-bang moment for Pop and everything that came after.

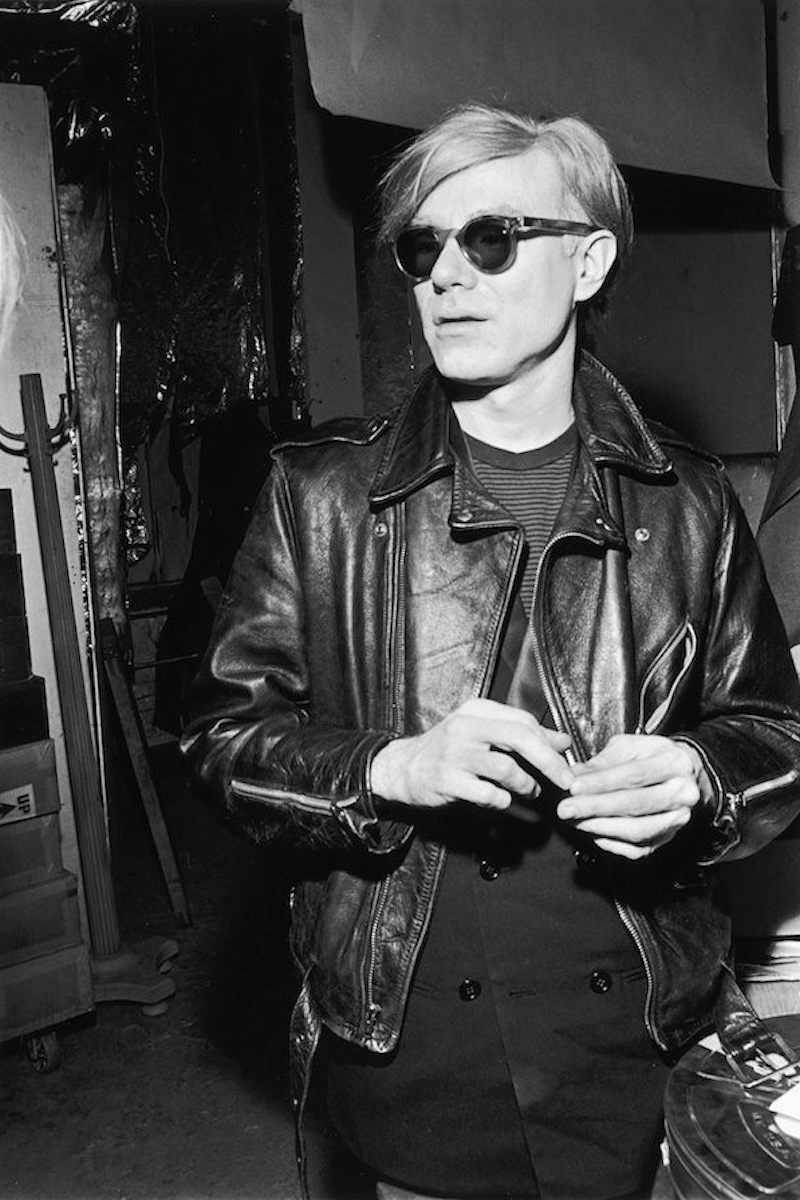

“Artists aren’t supposed to dress up and I’ll never look right anyway,” Andy Warhol utters in Bob Colacello’s biographical Holy Terror book. It epitomises the irony of Warhol – as although he wore black rollneck sweaters, Levi 501 jeans, leather jackets, Cuban-heel boots, thick wraparound sunglasses, and occasionally denim shirts in those early days of The Factory on 47th street, it did become a uniform. And moreover, this look was a deliberate act to help cultivate an air of mystery to his persona.

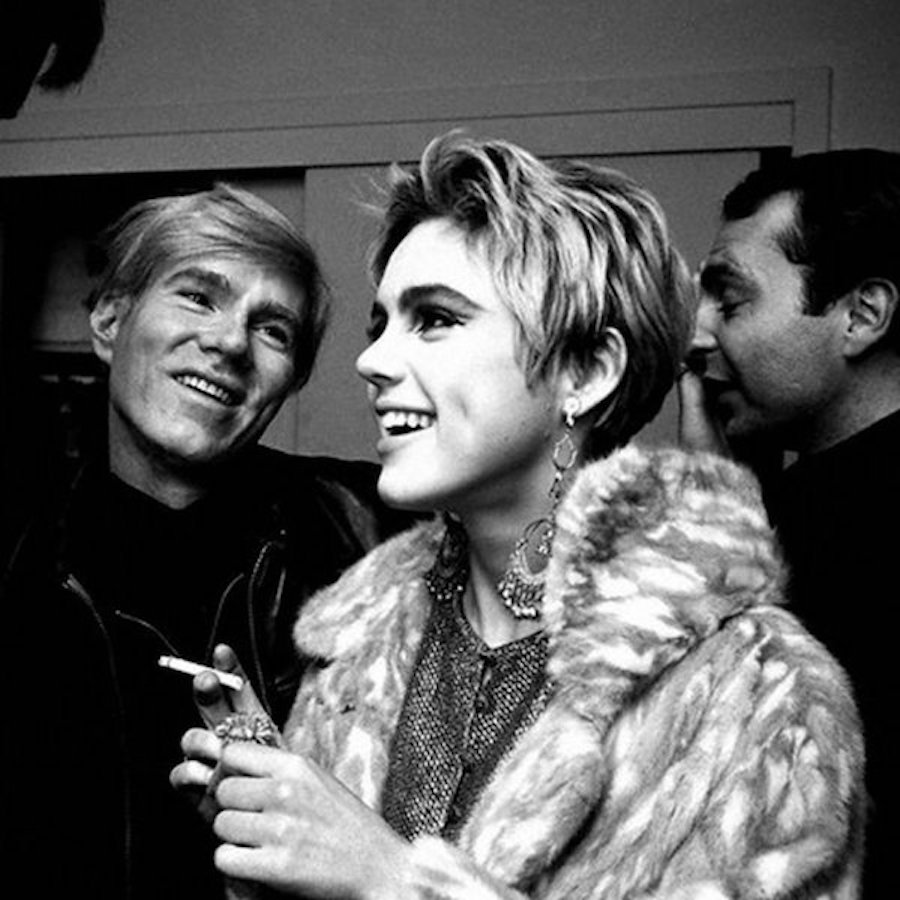

He met Edie Sedgwick in 1965, and held one-man exhibitions in Paris, notably at The Sonnabend Gallery that same year. As fruitful as the exhibitions were, meeting Sedgwick is arguably ‘the’ pivotal moment of Warhol’s career as she became the avatar of his desires. At times his silver wig was the only similarity to her metallic outfits, yet there were occasions when the both of them presented themselves in the style of the latter stages of Beatnik subculture. Wearing their signature Breton-striped T-shirts, it was a calculated move from Warhol to implement some of the sartorial inclinations of the Beat movement into The Factory. And with his tailored jacket and jeans look; it fitted right in with the notion of going from uptown dinner party to a downtown loft debauch. Whilst the aesthetical appearances of the duo played its part in supporting Warhol’s prophecy, Sedgwick was also the perfect buttress for “I have nothing to say – read my books”, Warhol’s standard riposte to most would-be interviewers. For a time on chat shows when Warhol was asked a question, he would only whisper the answer in Sedgwick’s ear to deliver to the host. Despite Warhol and Sedgwick falling out, the latter tragically dying of an overdose aged 28, those years not only helped cement Warhol’s ability to popularize the use of art as a reflection of society (in America’s case consumerism and superficiality), but in fashion terms it left an extraordinary legacy, that high fashion houses consistently try to play on.

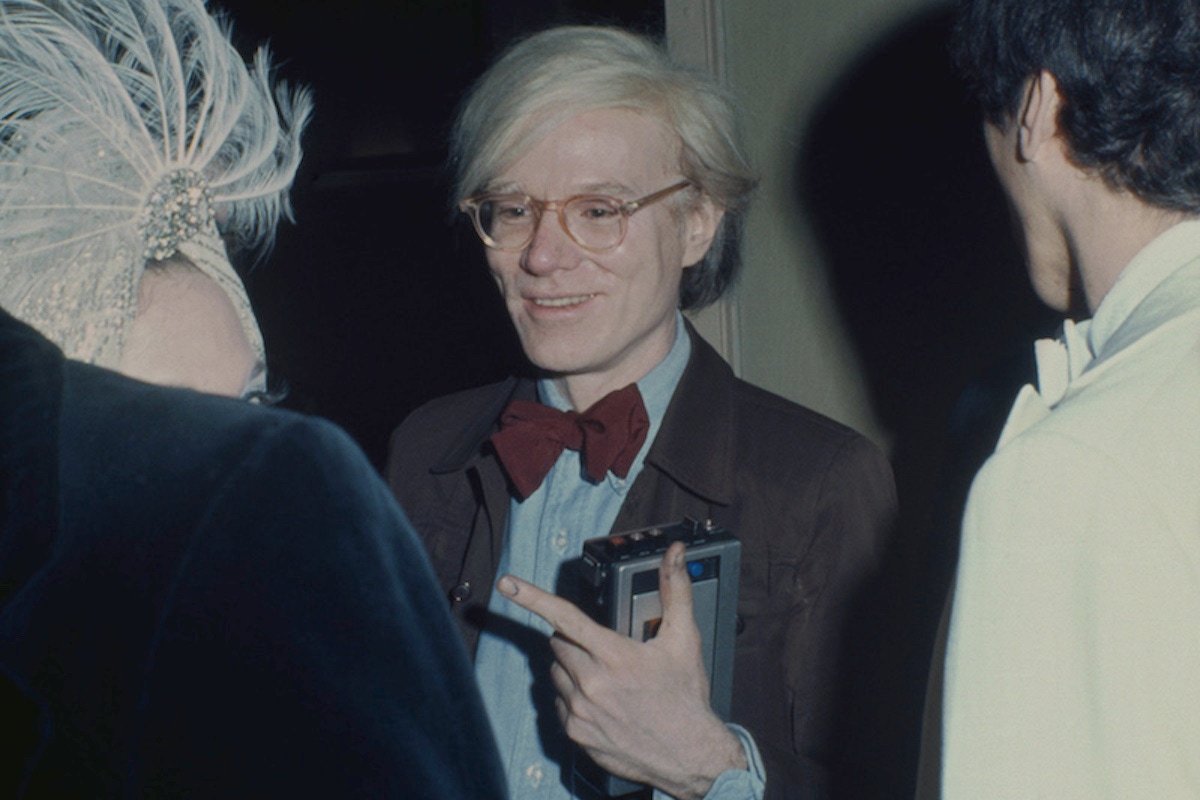

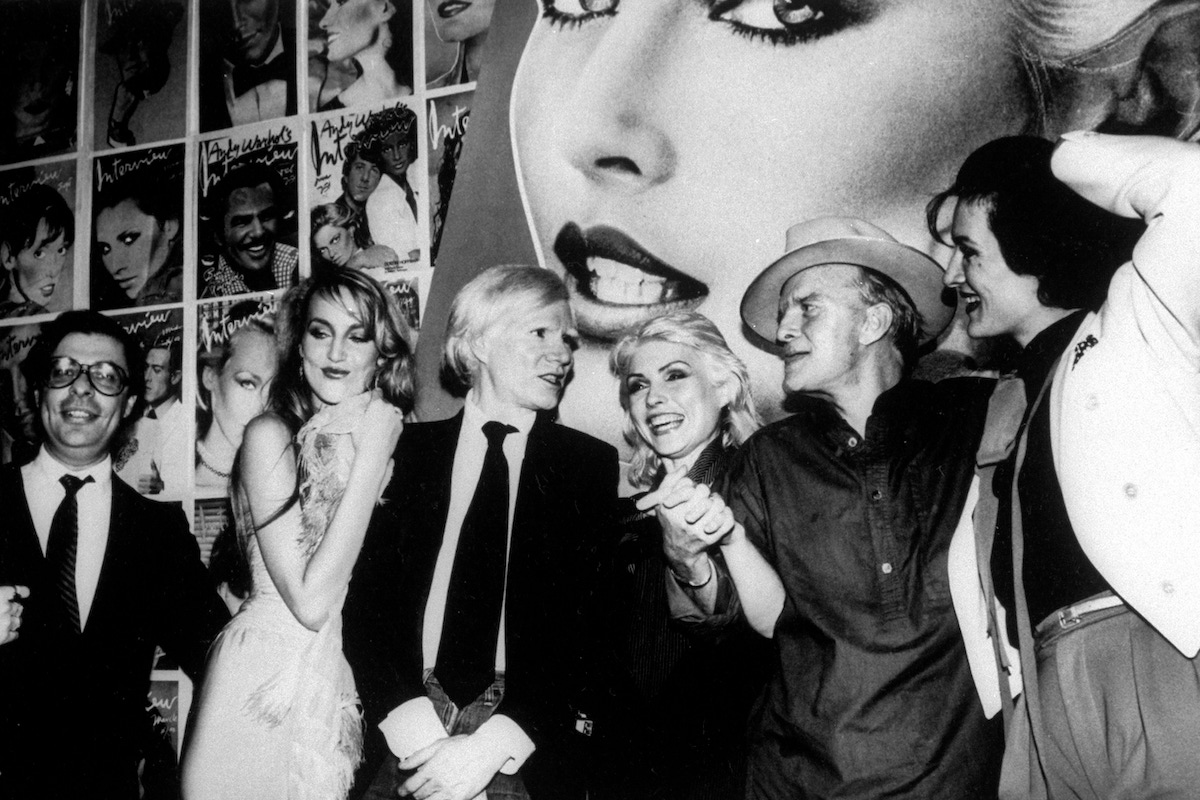

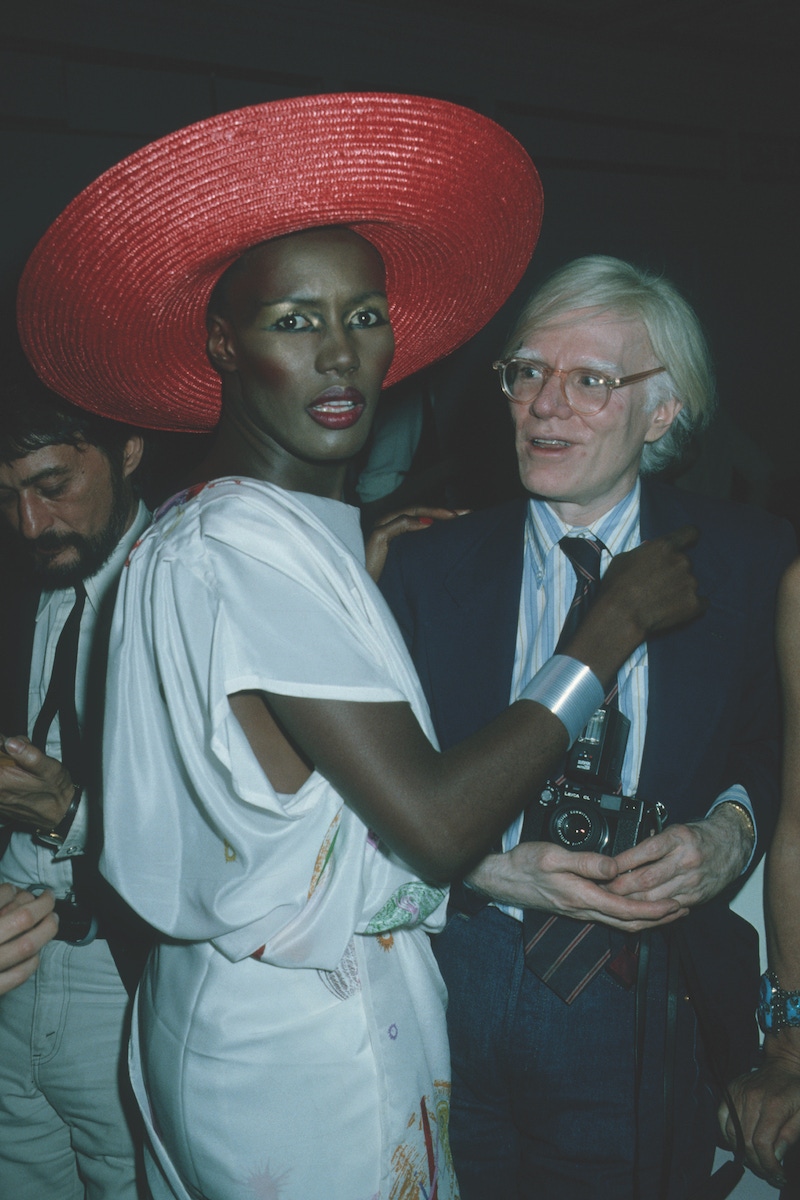

At the turn of the ‘70s only really the jeans and Chelsea boots remained from his signature look. “I want to die with my jeans on”, said Warhol. Perhaps this sentiment was the result of him being nearly fatally shot by radical feminist Valerie Solanas in the Factory in 1968. With the decade of nightclubbing in its height, notably Studio 54 from April 1977 to February 1980, it was jeans, either a white or wide-striped shirt, dark blazer, and tie or bow-tie that defined his look. Co-founder of Studio 54 Ian Schrager once said about his club: "If Mick Jagger came to your club, that was all you needed. Or Andy Warhol. When Andy Warhol went to a club, it was like the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.” Unlike Capote, who Warhol still took to Studio 54, the latter had been able to maintain those golden friendships with the glitterati of the time: Bianca Jagger, Halston, Jack Nicholson, Liza Minnelli to name a few – and it suited Warhol as it was the place for him to round up rich patrons for portrait commissions.

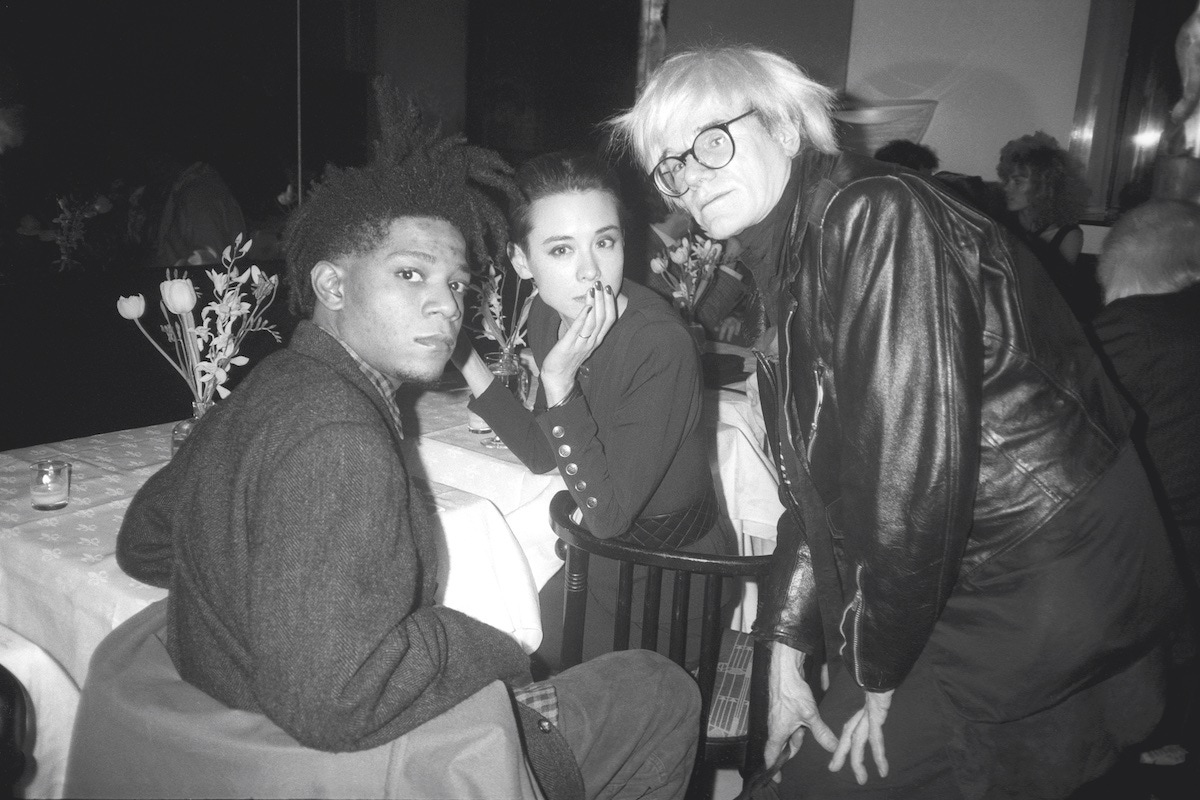

The 1980s was a sort of re-emergence for Warhol in terms of critical and financial success. His affiliation with prolific younger artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat increased his credibility. But even during the decade defined by kitsch and maximalist garments, his largely achromatic uniform remained. He spent chunks of his time at Mr Chow restaurant. Warhol held court at a long table, several times a week, “not eating”, said Michael, “just pushing his food around” He lived in trainers or Chelsea boots with a Cuban-heel, and even donned more subdued safari jackets. Yet according to Bob Colacello in his later days, when in the company of rich ladies’ he liked to unbutton his shirt to halfway to reveal his opulent diamond necklaces.

His work was hallmarked by a virtuoso of colour, but as part of his plan to create his persona, he maintained the use of darker tones. “A good plain look is my favourite look. If I didn’t want to look so ‘bad,’ I would want to look ‘plain’, said Warhol in The philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again), 1975. It summed up his stylistic strategy perfectly, yet with it he was able to never leave fashion.

Gianni Versace’s 1991 Pop art collection featuring a jewel-encrusted version of Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe prints truly made the artist synonymous with high fashion. And then there’s Diane von Furstenberg’s 2014 ‘Pop Wrap’ anniversary collection, or pretty much anything Jeremy Scott designs for Moschino. In May, Warhol’s silkscreen image known as “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn” is expected to sell for around $200m (£151m), according to auction house Christie's. It will make it the most expensive 20th century work of all-time, which is a measure of Warhol’s all-round creative influence and brilliance.