ART OR SEDUCTION?

John Derek was 46 years old when he fell for the charms of a 16-year-old Californian actress who would become Bo Derek. Nick Scott asks what made their fire burn until his death 25 years later…

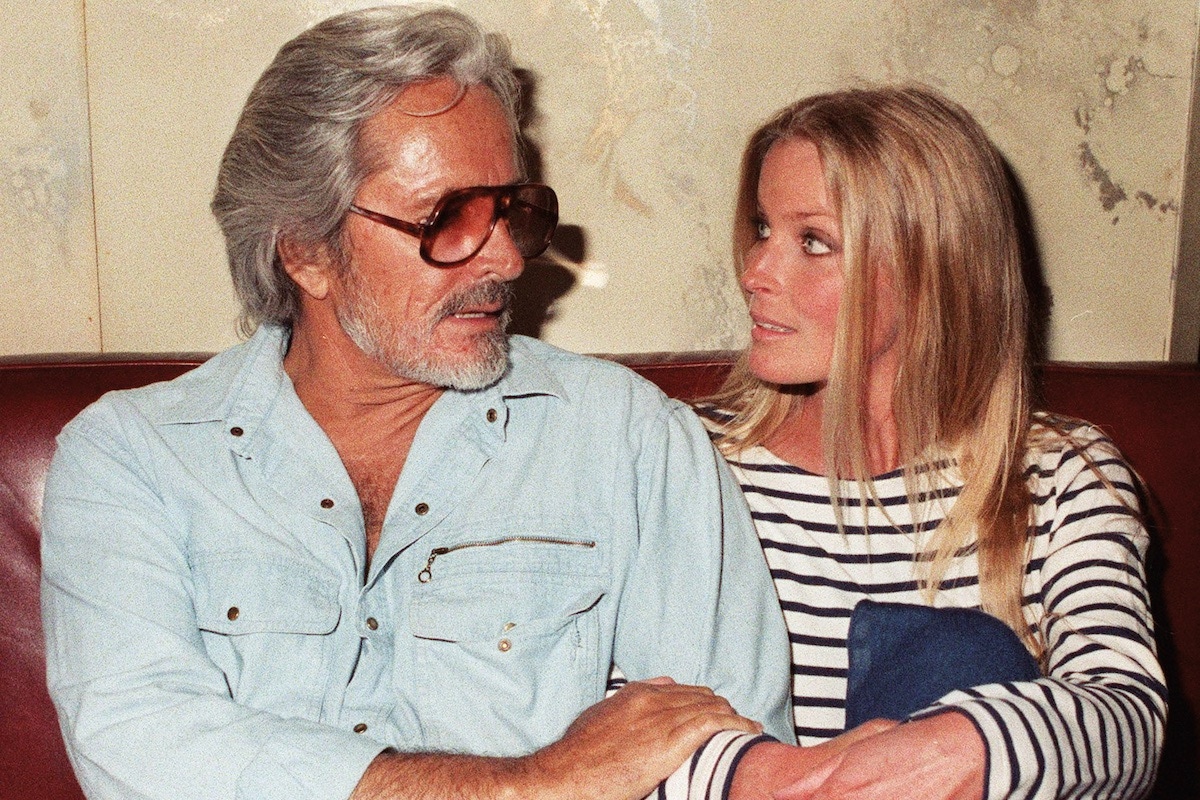

He was known as the quintessential Svengali — a word derived from George du Maurier’s 1895 novel Trilby — in which the title character, a singer, is entranced via hypnosis by the roguish antagonist, making her unable to perform without Svengali there to lead her to a state of reduced peripheral awareness. Aside from his clear-cut, leonine features and movie-star-turned-director/photographer status, what exactly was it that hypnotised Bo Derek about John Derek, a man 30 years her senior who became not just her lover but her mentor and sole creative collaborator?

Born Derek Harris in Hollywood in 1926 to the silent film maker Lawson Harris and the film actress Dolores Johnson, Bo’s beau-to-be had matinee idol looks that saw him, in his youth, singled out for a movie career by David O. Selznick (who cast him in minor roles as a boyfriend of Shirley Temple in Since You Went Away and a sailor in I’ll Be Seeing You) before he was drafted into the second world war. It was Humphrey Bogart who renamed him John Derek, and Bogart who then cast him as Nick Romano in 1949’s Knock on Any Door, a performance that led a New York Times reviewer to describe Derek as “plainly an idol for the girls”. All the King’s Men, released the same year, did nothing to yank him from that pigeonhole.

Then came a watershed moment that wasn’t. At least three people’s lives would have panned out differently had Bogart’s Santana Productions, having brought the film rights to mystery writer Dorothy B. Hughes’s novel In a Lonely Place, stuck to their original plans to utilise Derek’s youthful magnetism in the leading role. Instead, the writers decided to make the character much older, meaning Bogart could take on the part instead. The 1950 adaptation turned out to be a masterpiece, and remains a noir classic, while Derek’s fate fell into the hands of Columbia, who immediately made him a staple in swashbucklers such as Rogues of Sherwood Forest (1950), Mask of the Avenger (1951), Prince of Pirates (1953), and The Adventures of Hajji Baba (1954). A smattering of more impressive turns included 1956’s The Ten Commandments and 1960’s Exodus, but his star was set to fade faster than his looks would.

Columbia had channelled Derek’s career in this direction because he was a massive hit with young people, which proved a prescient observation when it came to how his personal life played out. A graph plotting the age gaps involved in John Derek’s nuptial endeavours would make alarming viewing for any father of a nubile young woman itching to break into the world of post-war Hollywood cinema.

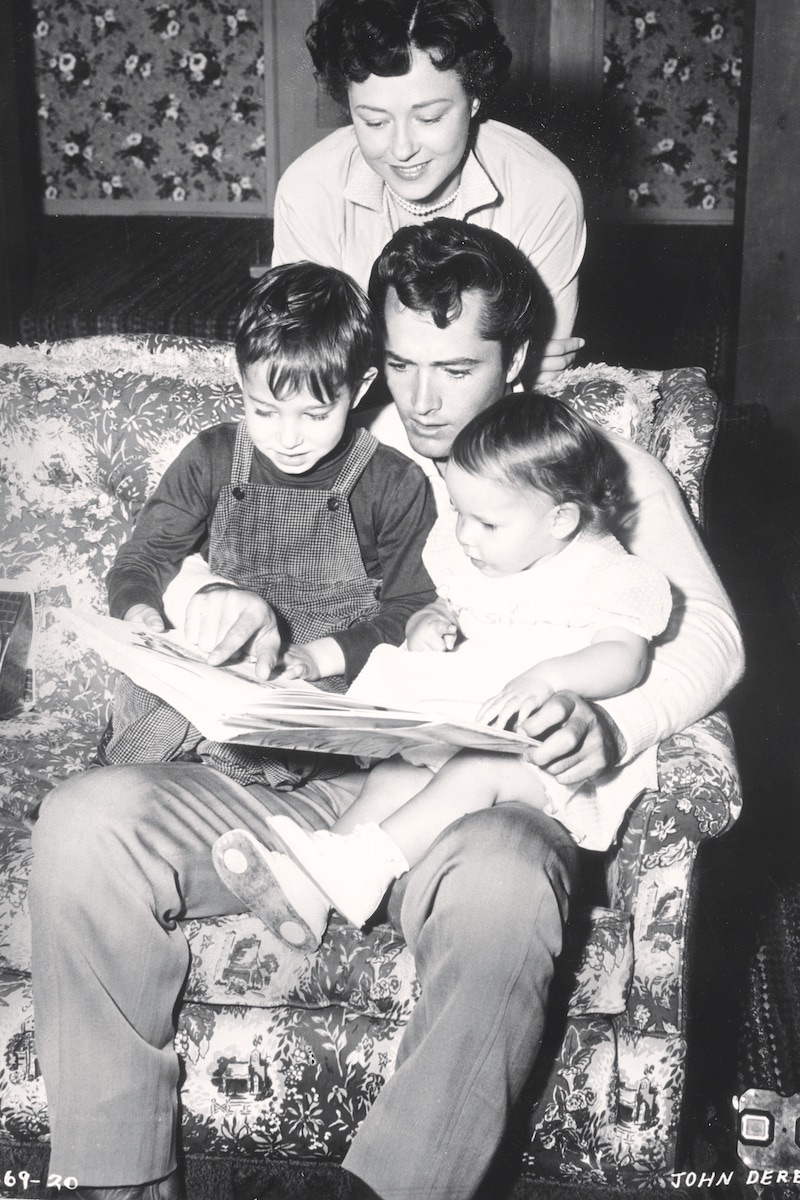

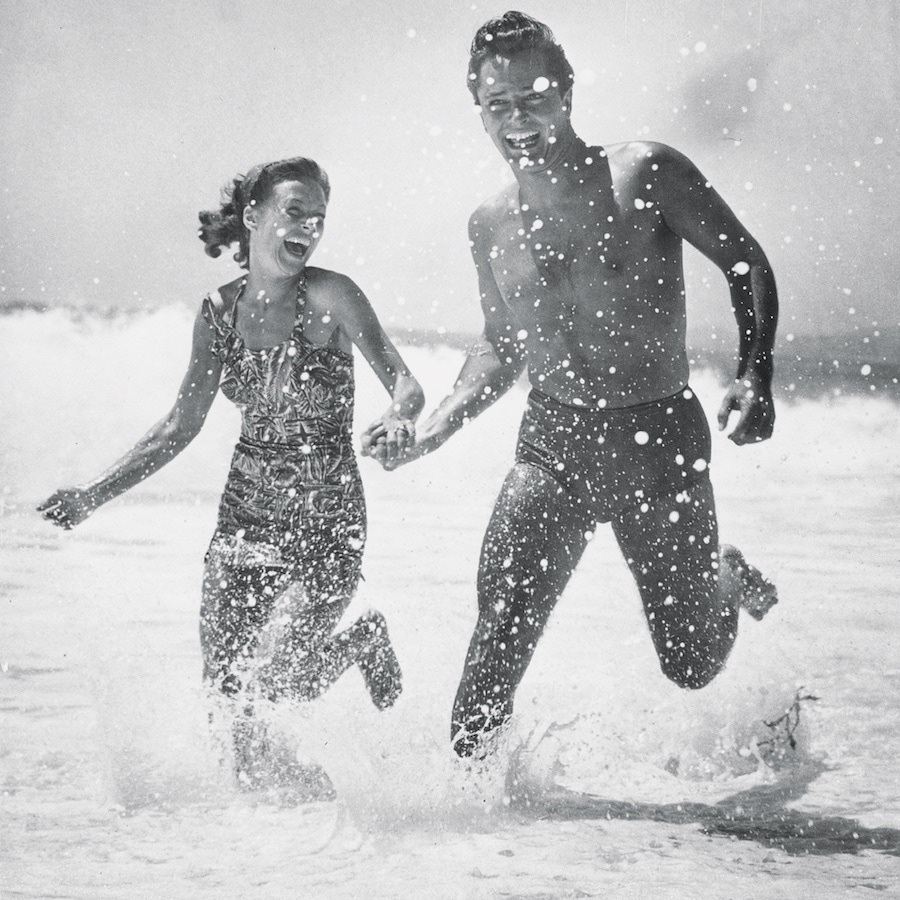

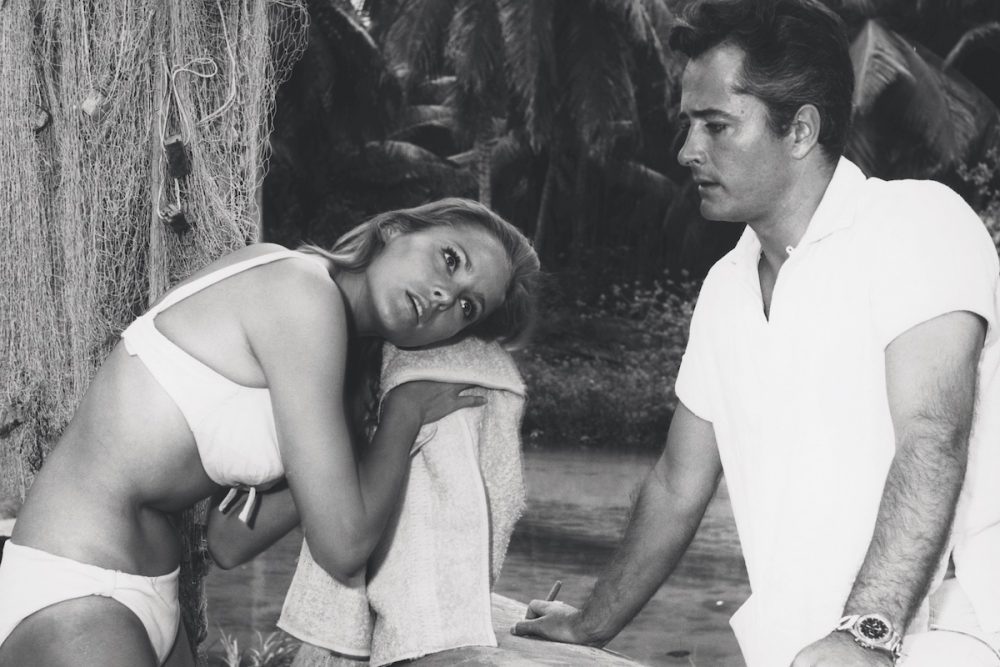

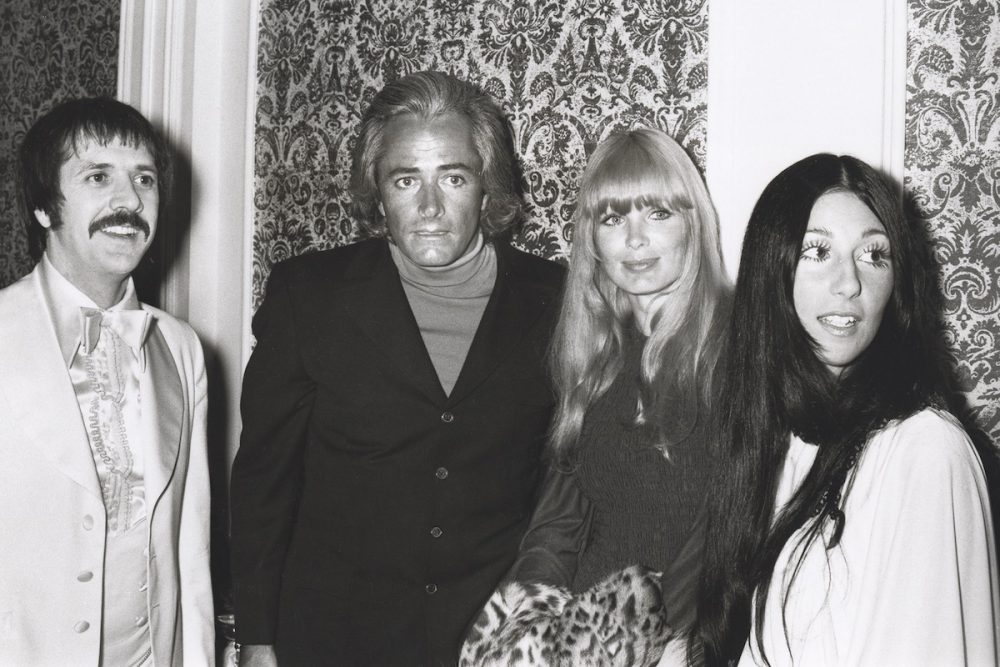

In 1948 he’d wed the French starlet Pati Behrs — four years his junior, so no biggie there — with whom he had two children. He married Ursula Andress, 10 years his junior in 1957, appearing alongside her in Nightmare in the Sun (1965) and Once Before I Die (1966), a film about soldiers and a lone woman striving for survival in the Philippines, where Derek had briefly seen action during World War II. His marriage to Andress ended when she began an affair with the French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo (a taste of what would become Derek’s own medicine), while his third wife (16 years his junior) was Linda Evans, who appeared in 1969’s Childish Things — a barely viewed movie directed and photographed by Derek — but who is better known as Krystle Carrington to American soap opera fans of a certain vintage.

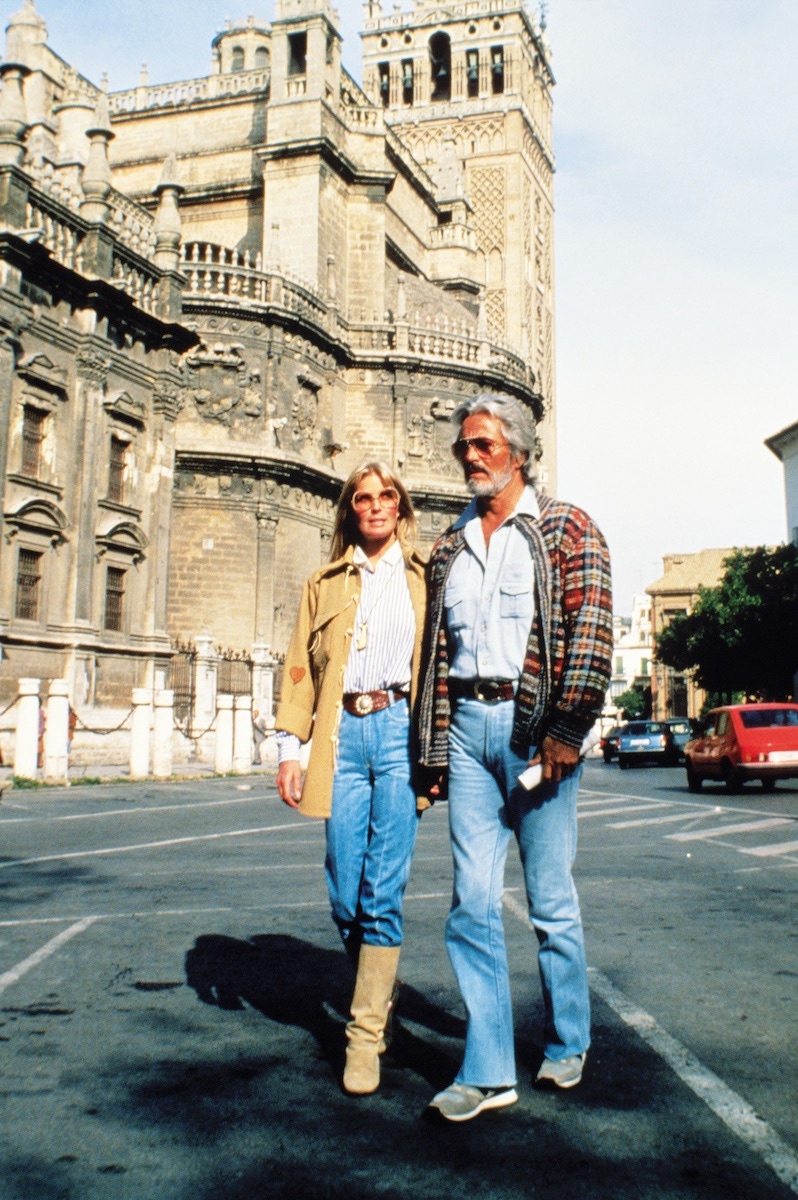

But around this time, the graph line takes a major hike — and it’s the shaft, not the heel, of the hockey stick (to borrow from Al Gore) that soars upwards here. In 1973, while directing a film on the Greek island of Mykonos, Derek was beguiled by the budding charms of Mary Cathleen Collins, a 16-year-old high school dropout from Southern California who was, between lengthy sessions on the beach, working under the stage name Bo Shane. He immediately cast her in the movie, And Once Upon a Time (later released as Fantasies), and embarked upon an affair with her, a motocross bike salesman’s daughter who was younger than his own children.

People assumed that, when the pair left Mykonos, their affair would fizzle out. Instead, Derek took Bo to Germany (arguably — probably — to avoid prosecution under California’s statutory rape laws due to her age) and after divorcing Evans, he and Bo married in June 1976. She was 19; he was 49.

Bo’s star continued to rise. She became something of an overnight sensation when she starred with Julie Andrews and Dudley Moore in Blake Edwards’s 10 in 1979. The movie’s title refers to the ultimate score a woman can achieve in being assessed for attractiveness, and the scene in which Bo steps out of the sea — one that, ironically, has echoes of Derek’s ex Andress in Dr. No — is enough to have most men thinking of a famous numerical quip in Spinal Tap.

Elsewhere in interviews of this time, Bo refers to his “volcanic” temper before interviewer Barbara Walters asks, “Do you have sexual fantasies?”, to which Derek replies, “I don’t have any unfulfilled sexual fantasies — I’ve been very fortunate that my fantasies are not so elaborate that I can’t have them. Mine are making love to the person that you love. Without love it’s gymnastics — and, Christ, I’ve never cared that much about exercise.”

The comments under the clips highlighted above include words like ‘narcissistic’ and ‘controlling’, not to mention a line from Joni Mitchell’s hit You Turn Me On, I'm a Radio: “And you don’t like strong women ’cause they’re hip to your tricks”.

Whatever the reality, when John Derek collapsed at the Santa Ynez ranch at the age of 71, and died of heart failure after undergoing surgery, their marriage had survived the scorn that greeted their films as well as their union for more than 20 years. In 2002, four years after Derek’s death, Bo embarked on a relationship with the actor and country music singer John Corbett, who is five years her junior.

It appears that John Derek was impervious to public disapproval. But in 2018, with gender relations having moved on and Hollywood under scrutiny in the sexual harassment scandal, it’s certain that a film made today about Derek’s life would be no hagiography. It’s also certain that, were the brushstrokes sufficiently intricate, it would make cryptic, and utterly compelling, viewing.

This article was originally published in Issue 56 of The Rake.