The Autumn/Winter of The Patriarch: Gianni Agnelli

All hail Gianni Agnelli, 'The Rake of the Rivieria'. We revisit his life, influence and lasting impact on the culture that underpins our magazine.

To celebrate the imminent fiftieth issue of The Rake, we look at three of the magazine’s most potent inspirations, spiritual founding fathers whose influence only emboldens during these turbulent times. Where better to start than the “King of Italy” himself, the richest man in modern Italian history and the "Rake of the Riviera" after whom the magazine was originally named. Patriarch of car manufacturer Fiat and owner of Juventus Football Club, he was made Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic in 1967, Knight of Labour in 1977 and a Senator for life in 1991. Such sway did he hold that, according to The Telegraph, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev once took him aside, amongst a gaggle of Italian cabinet ministers, and said: "I want to talk to you because you will always be in power. That lot will never do more than just come and go." He is, of course, Giovanni "Gianni" Agnelli.

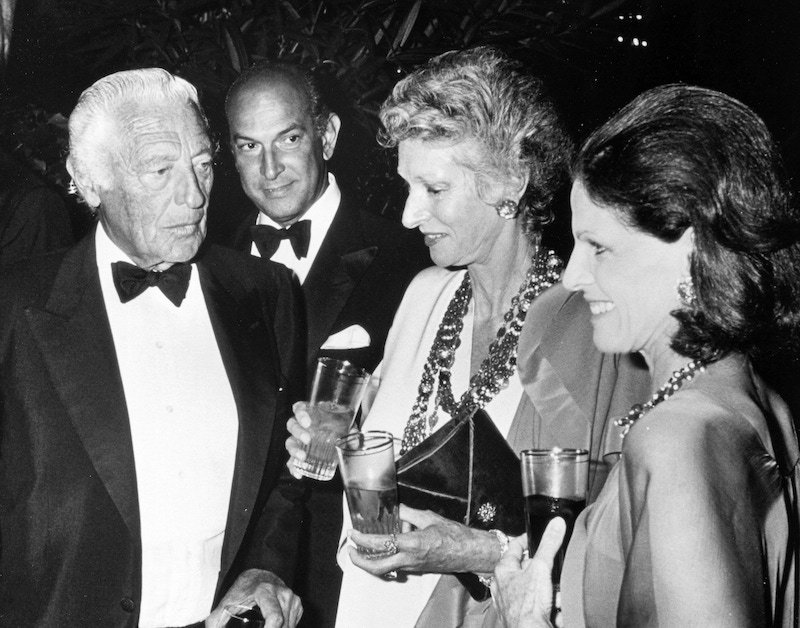

Born and raised in Turin, he studied law at the city’s university (hence another nickname, L’avvocato), but a reputed allowance of $1,000,000 a year allowed him to spread further afield. In addition to properties in New York and St Moritz, he threw mythical parties at the sumptuous 28-room Villa Leopolda on the Côte d'Azur, which in 2008 sold for 500 million euros, then the most expensive house in the world. Prince Rainier, JFK and Errol Flynn were amongst the regulars, and Agnelli's high-profile dalliances included Jackie Kennedy, Rita Hayworth, Anita Ekberg and socialite Pamela Churchill Harriman (after a row with whom he smashed his Ferrari into a meat lorry at 120mph).

Described by Life as having "the sculptured bearing of an exquisitely tailored Julius Caesar", Agnelli soon settled, relatively. In 1953, at the chapel of Osthoffen Castle, he married Donna Marella Caracciolo dei principi di Castagneto, a half-Neapolitan, half-American fabric designer, tastemaker and later Vogue model, she in Balenciaga, he on crutches after another car accident. In an excellent piece for Vanity Fair after his death, Marella described the Agnelli universe as less immoral than “freely amoral”, affairs and haute couture cheek-by-jowl with interminable philosophical disquisitions in crumbling Florentine villas. The seven siblings had a “tribal aura”: everyone looked the same, talked the same and laughed at the same jokes. Truman Capote would do gymnastics on their yachts and visit them in Verbier, before duplicitously mocking their way of life in his novel Answered Prayers.

All families, royal or industrial, are racked by succession problems (as an Observer profile of Agnelli noted) and Fiat was no different. Gianni was the grandson of Fiat founder Giovanni, after whom he was named. When grandfather Giovanni heard that the widow of one of his sons was having an affair with another man, he responded by kidnapping her children until Mussolini personally intervened to stop him. From a young age, Gianni slid through life with a Tolstoyan nonchalance, once teasing his lovelorn sister Susanna: “In love? I thought only servants fell in love!”

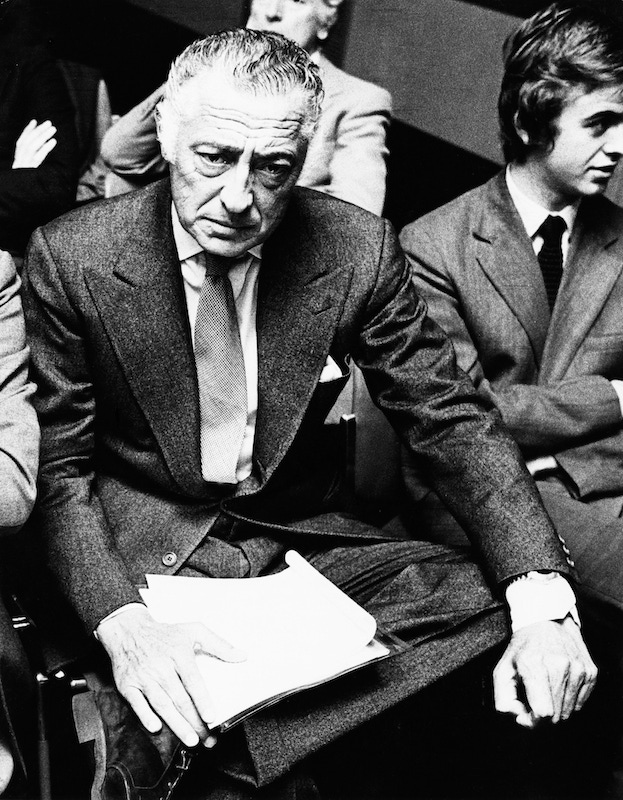

Having fought for the Fascists and later the Allies in the Second World War, wounded twice on the Russian front, Gianni took over the family business in 1966. The Observer reports that his attempts to diversify into banking, textiles, food, insurance and publishing were thwarted by slashed oil prices and labour unrest, especially when Fiat were caught spying on their own workers. Roman politicians also resented Fiat’s Torinese “state-within-a-state” arrogance. A corporate maverick, in 1976 Agnelli controversially sold 10% of Fiat to Colonel Gaddafi’s Libyan government. Through the shadowy Bilderberg Group, he also cultivated contacts like David Rockefeller and Henry Kissinger, who called Agnelli Italy's "permanent establishment". He weathered storm after storm and was eventually responsible for 4.4% of Italy’s GDP, the most vital symbol of Italy's post-war renaissance. Tragically, his only son Eduardo, potential Fiat heir and something of a lost soul more interested in mysticism than cars, killed himself in 2000.

Perhaps the Agnellian element that has most influenced The Rake was his taste. Designer Nino Cerruti named Agnelli one of his greatest fashion inspirations, alongside James Bond and JFK; Esquire hailed him as one of the five best-dressed men in the world. A mirror of his attitude to life, his style mixed the classic with the modern, bespoke Caraceni suits subverted with eccentric accessories, like a wristwatch over the cuff, or a tie askew, or brown hiking boots, or unbuttoned collars on button-down shirts. The subtlest fashion statements were quickly imitated across the world.

A ludic stillness of style complemented a lust for speed. His yacht Azzurra came third in the America’s Cup in 1983. Formula One champion Niki Lauda described being driven by Agnelli as one of the most terrifying experiences of his life. His private range of one-off cars (a Ferrari 360 Speedway, a bespoke Lancia Delta Integrale, a gorgeous open-top Fiat Multipla MPV) was rivalled only by his collection of contemporary art, which included Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and a series of portraits Andy Warhol did of the Agnellis in black polo necks. Of the various family seats, his favourite was the Villar Perosa, a baroque, mulberry-lined, eighteenth-century former hunting lodge in Piedmont. A bon vivant until the end, Gianni Agnelli died in 2003 at the age of 81, in his beloved Turin. His workers' slogan never seemed more apt: "Agnelli is Fiat; Fiat is Turin; and Turin is Italy".

Soberly realist under the pomp, Agnelli once predicted that “if in a few years’ time there are only two car-makers left, Fiat will not be one of them”. For all his wealth and contacts, the capitalist prince had a hardwired connection to his compatriots. When the seventies were plagued by terrorist attacks, his letter to The New York Times praised the inherent decency of the Italian people: “If we have had our Borgias, we have had our St. Francises as well - and millions of hard-working, law-abiding and good-natured people between them.” In Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s great novel The Leopard, Don Fabrizio (an aging nobleman redolent of Agnelli) suggests that “if we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change”. It is that mix of classic and modern, of permanence and change, namesakes building on the work of namesakes, that underpins the virile, cosmopolitan, astute, playful Agnelli and, more than ever, the ethos of The Rake.