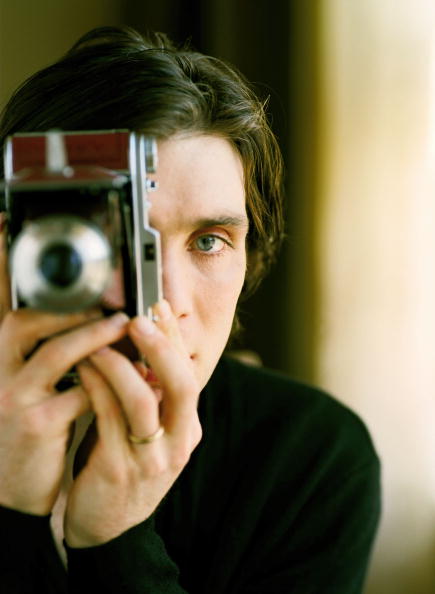

The Beautiful Scarecrow: Cillian Murphy

With features that could cut glass - and frequently a wardrobe to match - Cillian Murphy has become one of cinema's most absorbing presences.

Irish actors, like Irish writers, are particularly difficult to place within their national pantheon. Two main schools compete: the roisterers (Richard Harris, Peter O’Toole) and the quiet-eyed watchmen (Gabriel Byrne, Brendan Gleeson). Of the latest wave and by flitting between the two, Michael Fassbender brings the freshest nuances to the paintbox of male lust (for justice in Hunger; for sex in Shame; for power in Macbeth; for techno-immortality in Steve Jobs). But perhaps the country’s most mysterious screen presence is Cillian Murphy, the Banquo’s ghost to Fassbender’s murderous king.

Just look at that face: high-fashion cheekbones, dolphin pools for eyes, the petals of the mouth, the sculpted neck. The accumulative vibe is faux-infantile alien, soothingly sinister, tough and ethereal with a technical exactitude as sharp as his physique. Like his frequent collaborator Tom Hardy, Murphy has expanded the scope of the action genre by reducing it. Art, wrote GK Chesterton, is limitation: “the essence of every picture is the frame”. Murphy’s gloriously inventive new film Free Fire, released in the UK on Friday 31st March, is one long shootout, just as Hardy’s Mad Max: Fury Road was essentially one long car chase, or Murphy’s 2005 thriller Red Eye one long disastrous flight, or Hardy’s Locke a single motorway journey…

The son of a French teacher and a civil servant, Murphy played guitar in a series of bands with his Beatles-mad brother and was even offered a record deal. He turned it down to pursue acting when he blazed onto the theatre scene in Edna Walsh’s play Disco Pigs having harangued the director for a part (Murphy has admitted to chasing directors with whom he particularly wants to work).

For Danny Boyle (another complex patriot), he led the London zombie horror 28 Days Later. Opposite a priest played by Liam Neeson (an actor Murphy sees as a father figure), he played a trans singer on the hunt for his mother in Neil Jordan’s Breakfast on Pluto, a far cry from his role in Ken Loach’s Palme d’Or-winning IRA drama The Wind That Shakes The Barley. For his Batman trilogy, Christopher Nolan reunited Murphy with Neeson to play The Scarecrow, a villain so disquietingly vivid it seemed to reinvent the rules of fear itself in mainstream film (like Hannibal Lecter, he’s not even on screen that much). Nolan was so impressed that most of Inception takes place within the mind-mountains of Murphy’s sleeping business heir.

Yet Murphy’s most textured work has come not in cinema but on television, in Peaky Blinders, the best-tailored series since Mad Men. Murphy’s Thomas Shelby is a shrewd, persuasive paterfamilias calcified by war who approaches crime, like Idris Elba in The Wire, as an economically rigorous business. In exchange for protection, Shelby strikes a deal with a local tailor to style his family for free, an ingenious writers-room flourish that justifies the show’s infinite wardrobe of three-piece tweed suits, starched detachable collars and razor-lined flat caps. With shaved sides and a soft Birmingham brogue, Shelby is nonchalantly irresistible. Here, for example, is his overture to an aristocratic racehorse owner (played by Tom Hardy’s real-life wife Charlotte Riley) who’s invited him to stay the night at her stately home:

“Do you have a map? Because I'm not going to be able to find my way in the dark. You see, at midnight, I'm going to leave my wing and I'm going to come find you. And I'm going to turn the handle of your bedroom door without making a sound and none of the maids will know.”

The spirit of Valmont’s sex-as-conversation lives on, more erotic for being fully clothed. That same eloquence helps Shelby against heavyweight antagonists Tom Hardy (him again) and Paddy Considine. To a soundtrack speckled with Nick Cave and PJ Harvey, the show’s violence rasps and scorches, splits and thunders, the smeary under-chaos to the sartorial poise, but Murphy handles both elements with haunted aplomb (his assassination of an upper-class officer at Cheltenham Racecourse is as potent and visceral as Al Pacino’s murder of the two policemen in The Godfather).

Murphy, who turned 40 last year, lives in Dublin with his wife and children to be closer to his parents, elegantly detached from fame’s trappings. Later this year, he reunites with Messrs Hardy and Nolan for war epic Dunkirk, the latest in the actor’s canon of nightmarish imagery (scarecrows, zombies, bladed caps, doomed flights, lost mothers, condemned fathers). But he re-enchants these nightmares with the hope and haze of dreams. In Samuel Beckett’s first novel, the aptly titled Murphy, the hero sets fire to himself after losing a game of chess and dies “with fool’s mate in his soul”: he has a “curious hunted walk, like that of a destitute diabetic in a strange city”. That could be Cillian on screen, except he checkmates every opponent he faces. If Peter O’Toole was a gorgeous gargoyle. Murphy is a beautiful scarecrow, a fine-featured horrorshow, a plutonic skeleton with bones of wind. His midnight sun, having no alternative, continues to dazzle.