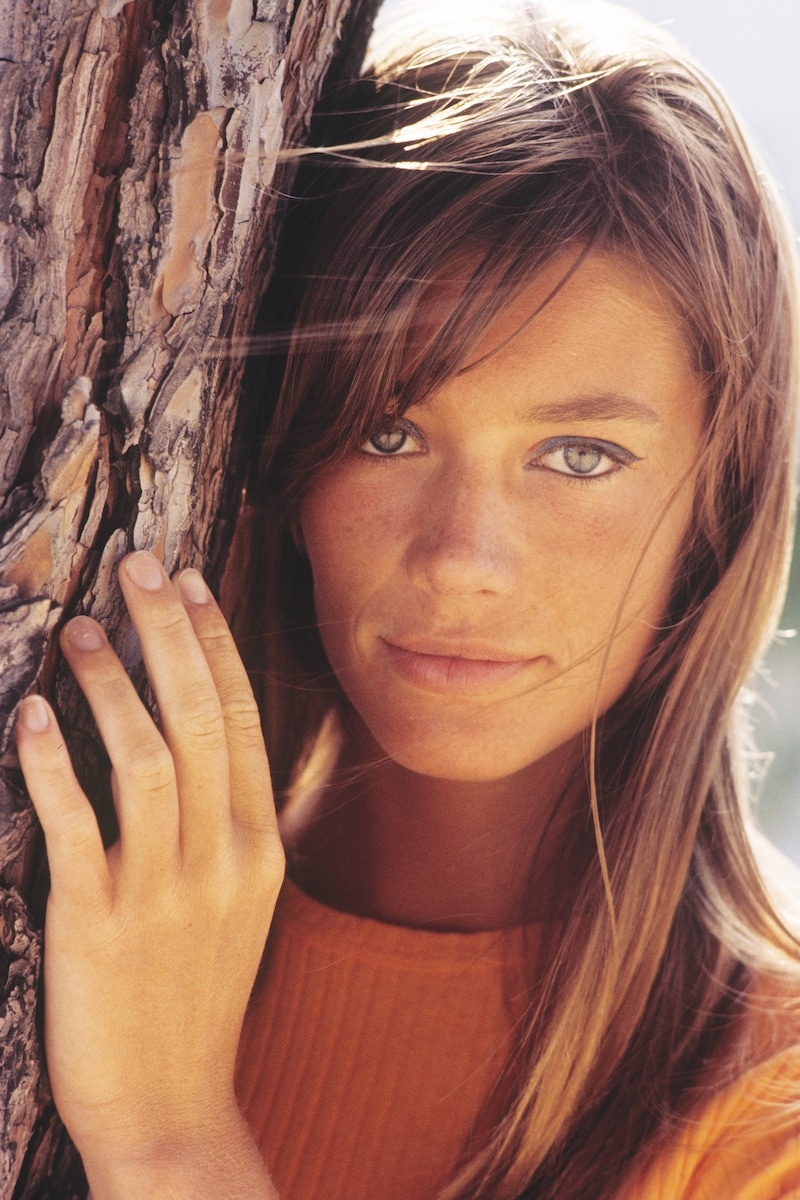

BLUE-EYED GIRL

‘What a person sings,’ Françoise Hardy once said, ‘is an expression of what they are.’ Hardy, the acclaimed chanteuse, used sadness and light to turn the pop ballad into an art form.

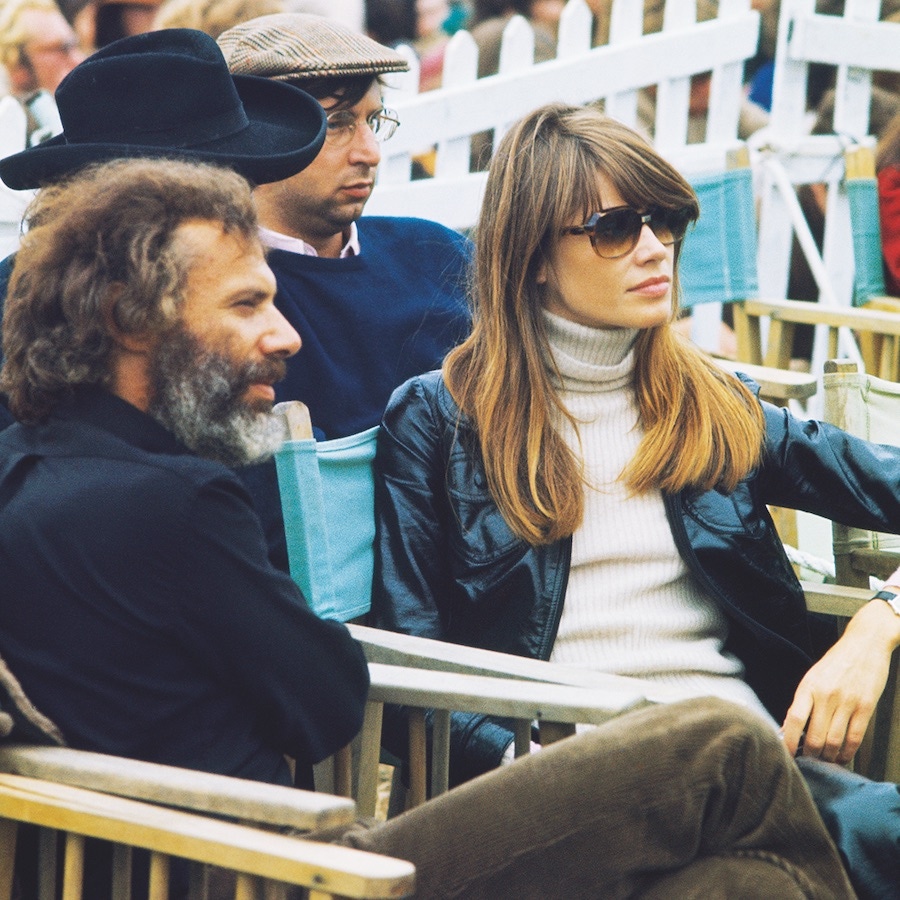

On the evening of May 24, 1966, his 25th birthday, Bob Dylan was due to play his first concert in Paris. But there was a slight hitch: he was refusing to take to the stage of the Olympia theatre unless Françoise Hardy came to see him immediately. Though he’d never met her, he’d already penned a Beat poem tribute to her on the sleeve of his fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan (“for francoise hardy/at the seine’s edge/a giant shadow/of notre-dame/seeks t’ grab my foot/sorbonne students/whirl by on thin bicycles... ”) Hardy obliged, and the gig went ahead. Later, she went with Johnny Hallyday to a gathering at Dylan’s suite at the Hotel Georges-Cinq, where Dylan beckoned her into his bedroom, placed an advance copy of Blonde on Blonde on a turntable, and played her two songs: I Want You and Just Like a Woman. “His meaning could not have been clearer,” she later told The Guardian. “But I was too busy listening intently to the songs, which sounded entirely different to anything I had heard before.”

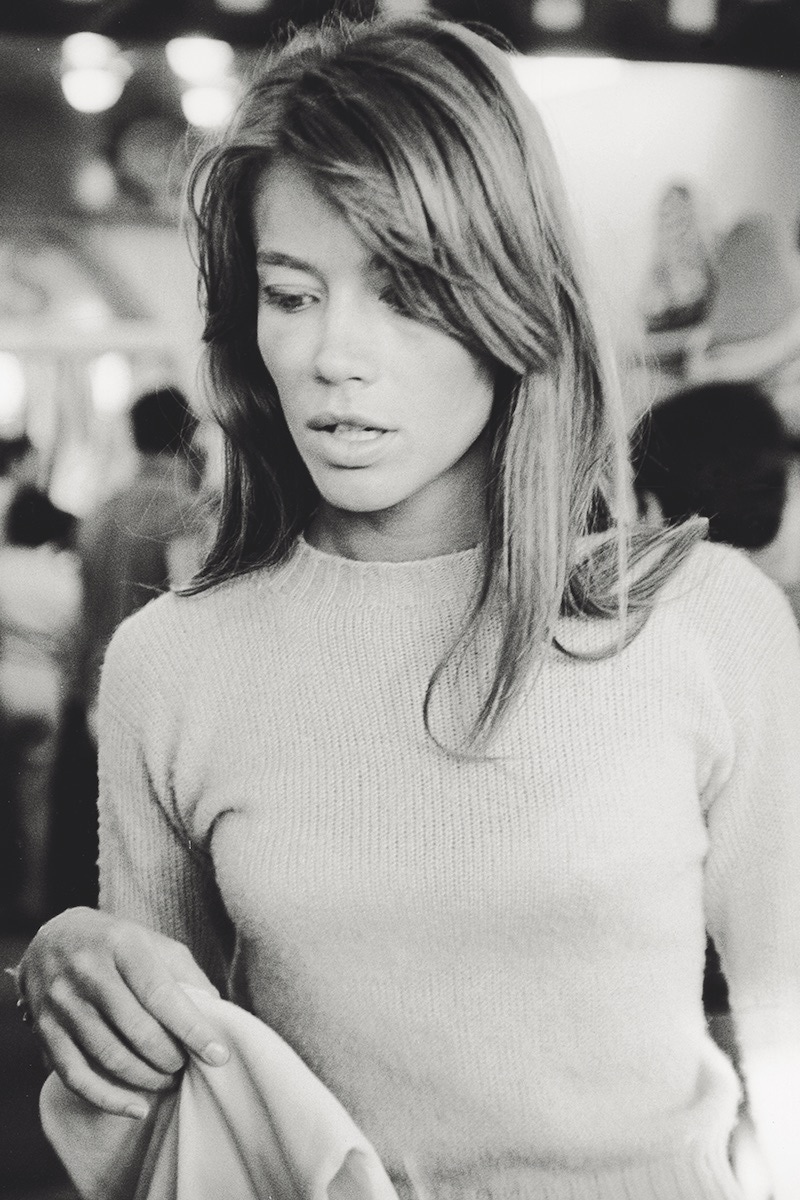

This anecdote — Dylan, helplessly besotted; Hardy, unwitting, preoccupied with chord changes — sums up the enduring allure of one of the most charismatic singers that France, or anywhere else, for that matter, has ever produced. She had shot to fame in 1962 with the self-penned Tous les Garçons et les Filles, which sold more than two million copies in France in 18 months — more records than Edith Piaf had managed to shift in 18 years. Hardy was immediately hailed as one of the leading lights of France’s insurgent yé-yé pop movement, but it was quickly apparent that she had little in common with her anointed peers — the perky brashness of France Gall, say, or the bubblegum of Brigitte Bardot. Hardy’s voice, plangent and elegiac, chimed with her subject matter; in Tous les Garçons... the singer finds herself wandering the streets alone amid a sea of couples (“Oui, mais moi, je vais seule par les rues, l’âme en peine/Oui, mais moi, je vais seule, car personne ne m’aime...”). She professed an affinity with the French chanson tradition, in particular the songs of Charles Trenet, saying: “He teaches me more than the others because his music is sad and light.” It was a description tailor-made for her own oeuvre; in hits like Je Pense à Lui or Rendez-vous d’Automne, the accent is always on the pense or the automne.

Hardy had the gift of sounding artless and untutored; likewise, her stunning beauty — the long, androgynous silhouette, the austere elegance, the preternatural poise — was all the more captivating for the fact that she seemed blissfully unaware of it. “She was the anti-Bardot,” wrote Vogue, “rendering the exaggerated femininity of the sex-kitten old fashioned.”

Hardy’s predilection for the plaintive had been instilled early. She was born in Nazi-occupied Paris in 1944, the daughter of Madeleine, a beautiful young working-class woman, and Étienne, her much older and wealthier married lover, who never lived with his secret family (much later, in her 2008 memoir, The Despair of Monkeys and Other Trifles, Hardy would write of her father’s life as a closeted homosexual — he came out in his later years — and of her younger sister, Michèle, a paranoid schizophrenic who died in 2004). Her mother “lived like a nun”, she told The Guardian, working long hours to pay for her daughter’s convent education. Weekends at her grandparents’ house failed to provide the shy, withdrawn Hardy with much respite: “My grandmother told me repeatedly that I was unattractive and a very bad person, which makes you think as a child that you will never meet anyone.”

Read the full feature in Issue 80 of The Rake - on newsstands now.

Available to buy immediately now on TheRake.com as single issue or 12 month subscription.

Subscribers, please allow up to 3 weeks to receive your magazine.