George Raft: Hollywood's Forgotten Star

George Raft was better known for making other actors’ careers a success. Yet the fact he had a Hollywood life at all was, in Raft’s eyes, a tale of triumph over circumstance...

George Raft didn’t want to give the name. Interviewed in 1980, his final television appearance, the then 85-year-old actor, dressed stylishly in a charcoal peak-lapel suit over a black polo neck, was asked about his habit of giving money to those struggling to break into his fickle industry. The interviewer pushes him and he declines. He pushes again; again, Raft declines. The interviewer jokingly lets slip that the recipient in question went on to become the biggest name in television. Raft smiles. Still he won’t name her. Raft is, the interviewer says, too much of a gentleman. The interviewer takes another approach. How about all the famous women he’d dated? Would he name them? Raft smiles. “You can name them,” he says.

Other men of his era — James Cagney, Spencer Tracy, Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, Gary Cooper — entered the annals of cool. But the much-less-famous Raft embodied it. They played tough; he was tough. They played gentlemen; Raft was one. “I respect women,” Raft once noted in another interview. “In one movie I was asked to hit Marlene Dietrich. I said I didn’t want to. That’s not something I would ever do in real life. And, of course, they said, ‘Well, you must’. Marlene said, ‘You have to hit me’. And I said no. So [filming was held up] for a couple of days. And I finally did hit her.” Years after the event, Raft was still not happy with it.

He had separated from his first wife a few years into their marriage, but supported her until her death some 50 years later. It was worth noting that he was the only man on the chat show who stood up when a woman came onto the stage. Yet gentlemanliness, apparently, got you only so far. Why, compared to his peers, is Raft so little known? “Well, I was a pretty quick study — but then I didn’t have too many lines,” he said. Raft made self-effacement an art form: he never saw himself on screen and, he claimed, never had any desire to. “I always played the guy with the gun, or something like that. I did 105 pictures and I was killed 85 times. How unlucky can you go, right? I did pretty well with the girls. But in the pictures, always got killed. I worked with so many Academy Award winners. They always won the award, not me. I was nominated once. I ran fourth.”

Raft, it sometimes seemed, made other men’s careers. Poor professional choices — at least in hindsight — were an issue: mistrust of novice directors, a belief in his own agent’s press releases and a reluctance to play un-redeeming anti-heroes all influenced his decisions. He turned down the lead in High Sierra, creating an opening that would help Bogart start his climb out of the doldrums. He turned down the lead in The Maltese Falcon for good reasons, but all the same he passed on what is widely considered the best detective movie of all time. Bogart took that part, too.

Studio head Jack Warner even considered Raft for the lead in Casablanca. The part went to Bogart, making him a legend. Warner soon after annulled Raft’s contract. Raft’s last movie, released in 1980? The Man with Bogart’s Face. Raft, by the by, had once saved Bogart’s life, when he managed to bring to a stop a runaway truck they were both in for a scene.

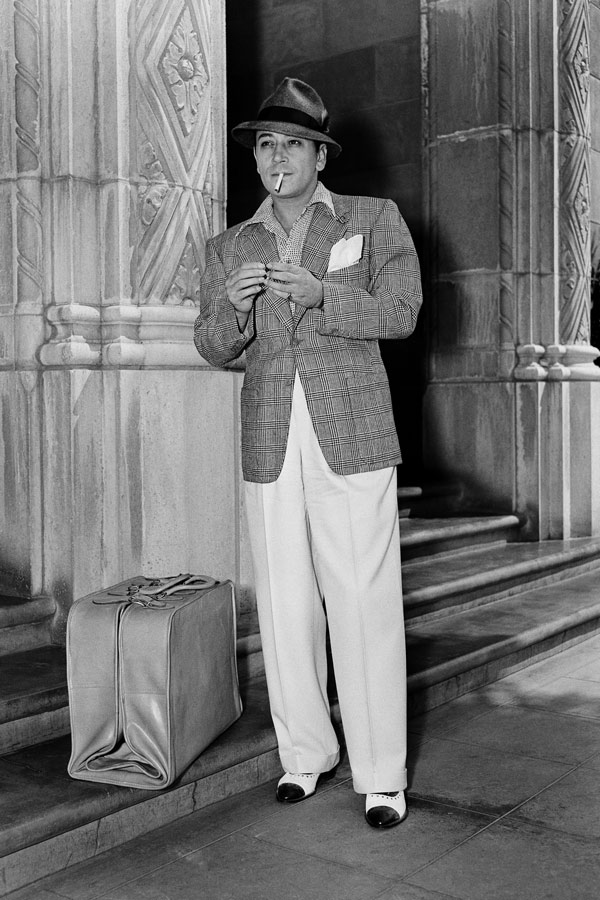

Of course, for all that Raft was the outsider, uneasy about his abilities, he did O.K. He was still appreciated as a dapper man around town: he popularised what became a signature, the wearing of a white tie with a black shirt, as well as several other trends of the era, like black pinstripe suits and long roll-collars. He also made a number of what are considered to be authentic, seminal movies: Scarface (1932); Each Dawn I Die (1939); They Drive By Night (1940); Nocturne (1946); and, as a supporting actor, Some Like It Hot (1959). Most of his movies were box office successes. In 1933 he was reported to be Hollywood’s highest paid star. He got his hands wet in cement outside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre as early as 1940.

But by the post-war years his fledgling super-stardom was all but sidelined, with Raft reduced to working as a goodwill ambassador to a Las Vegas hotel, lending his name to a discount chain that went bust, running a casino in Havana until Castro took power, or riffing on his screen persona by playing a prison inmate in Alka-Seltzer commercials. “I turn up, deliver a line, and it’s a big hit,” he once said. “I think the one-liner [commercials] are great because you’re in and out. I have no idea what the commercial is about.”

Still, Raft often expressed his amazement that he had made any kind of life in Hollywood. His was the rollercoaster experience, enough to warrant a 1961 biopic. Born into poverty in New York in 1895, and said to be nearly illiterate for much of his adult life, making him “for years the loneliest man in Hollywood”, as he put it, Raft did whatever he could to get by. “What can a guy do with no education?” he asked. "How I got into the pictures, I just don’t know. They just picked me up. I was sitting in the Brown Derby on Vine St. [in Los Angeles] and this director walked up to me and said he’d like to put me in a movie."

The work was satisfactory — by Raft’s own assessment, he was never an incredible actor. Indeed, in pursuing the movies he left behind a life as a successful vaudevillian, a self-described “song and dance man”. It’s a fact that makes for an uneasy chapter of his legacy. Ever the menacing tough guy on screen — “the only way the public would accept me”, he claimed — Raft’s believability was underscored by supposed connections to the criminal underworld and his love of low-life lingo (when once accused of winning $18,500 in a crooked dice game, Raft complained that he’d “never played with loaded ivories in my life”).

All the same, he got caught up in tax evasion, was questioned about the gangland hit that killed his childhood friend ‘Bugsy’ Siegel in 1947, testified in 1966 before a federal grand jury investigating Mafia financial transactions — he never commented on his testimony — and the following year was banned from England as an ‘undesirable’ for his supposed unsavoury connections.

Sometimes Raft’s knowledge of the underworld just slipped out. He once told the director Frank Tuttle that he couldn’t shoot a scene in which his character held up a post office. “Why not?” Tuttle asked. Raft went on to explain that that was “a federal rap” and that “no gunman in his right mind fools around with Uncle Sam”. The scene was re-written to take place in a tourist bureau.

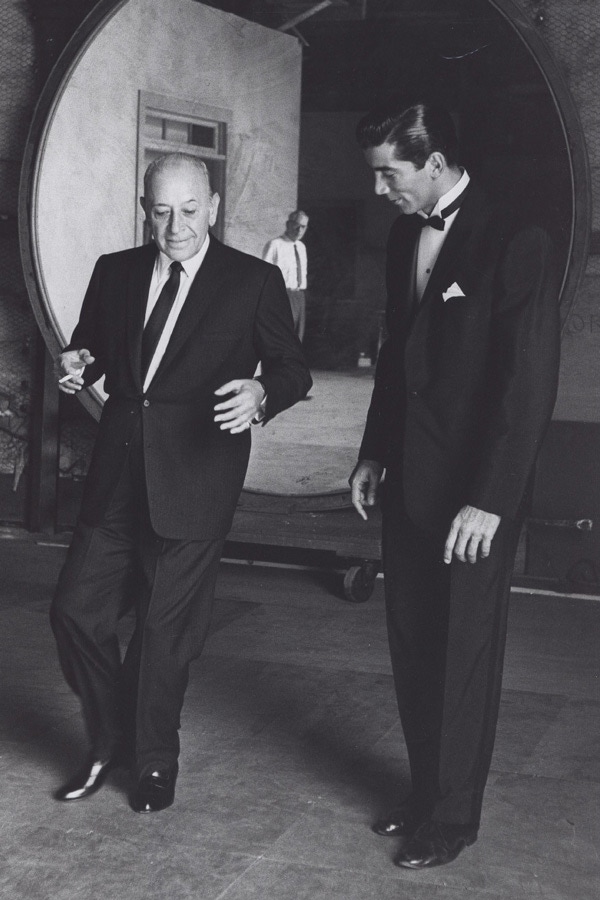

Yet contrary to the machismo, real or imagined, Raft really could dance, a product of one of his more successful employments, as a nightclub dancer (often in Mafia-owned joints). He moved fluidly, effortlessly — Cagney compared him with Fred Astaire on this score — even if, of course, Raft always claimed he was “never a good dancer. I was more of a stylist”. Just check out scenes in Take a Look at Her Now (1929) or Bolero (1934) or Broadway (1942). It’s hard not to conclude that his career took a wrong turn down a figurative and — given his C.V.’s preponderance towards gangster flicks — literal dark alley.

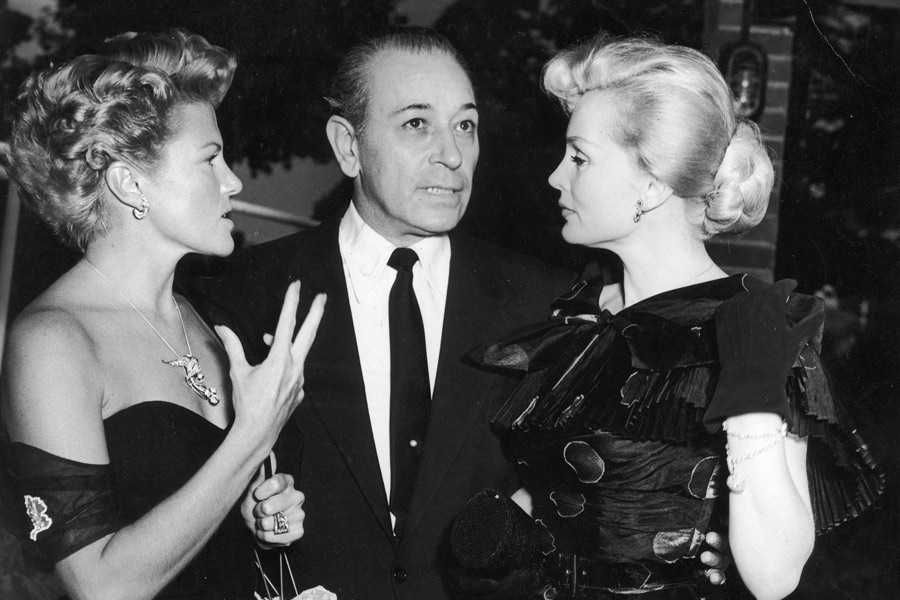

That romantic-hero typecasting never happened, of course; at least not on screen. If Raft’s movie choices were sometimes poor, his taste in women was excellent. Married only once, Raft’s affairs included those with Dietrich, Betty Grable, Virginia Pine, Carole Lombard, Norma Shearer and Mae West. Indeed, it was said that he ended up in Hollywood because he was on the run from a “crazy man who wanted me to marry his wife”. Inevitably, his name would be cited as a correspondent in divorce suits by countless angry husbands.

But this was all part of the performance of Raft’s life story. His work, and a lack of commitments, gave him decades of high living and handouts for strangers, such that when Raft died, of emphysema, there was next to nothing of his $10 million earnings left. “I wish I knew where it went,” he said. Most likely, he knew very well where his money went. Pre-figuring footballer George Best’s famous line, on another occasion Raft made the hedonistic calculation: “Part of the loot went for gambling, part for horses, and part for women,” he said. “The rest I spent foolishly.”