It Was a Wonderful Life: The Women of the America’s Post-War Splendour

Truman Capote famously called them ‘swans’ — for their combination of looks, sophistication and long-necked hauteur. Babe, C.Z., Slim and girlfriends personified America’s post-war splendour, and they did so with elegance, style and restraint. Compared with today’s Insta influencers, theirs was a radical beauty, writes Stuart Husband.

There’s a photograph taken in Palm Beach in 1955 that seems to encapsulate the breezy allure of post-war America. The Vogue model and socialite Patsy Pulitzer, unscrubbed but poised in pleated shorts and a print blouse, poses nonchalantly on a seaplane. She looks equal parts high society (the granddaughter of Joseph Pulitzer, who instigated the eponymous prizes, she would go on to marry Lewis Thompson Preston, the president of the World Bank) and vigorous outdoorswoman (three years earlier she’d caught a marlin weighing 1,230lbs, then a world record for a woman, off the coast of Cabo Blanco, Peru, leaving the likes of Ernest Hemingway trailing in her wake).

Pulitzer and her peers represented a new ideal of American beauty that coupled an urbane self-possession with the drive and rangy energy of the U.S. itself, a country that, in the 1950s, was “swollen with production and pleasure”, as the critic Robert Hughes put it in his book American Visions, in contrast to “the pinched and traumatised life of a Europe flattened by bombs”. Along with a burgeoning cultural cachet, from the allure of Hollywood to the birth of the cool strains of jazz and bebop and the zipping and dripping of abstract expressionism, American society now spawned a new class — the stylish rich, as opposed to the hidebound blue bloods or the vulgar nouveaux — who, as the author Truman Capote put it, were “heaven’s anointed, the only truly liberated people on Earth”. He went on: “The freedom to pursue an aesthetic quality in life is an extra dimension, like being able to fly” — on a seaplane, perhaps? — “where others walk. It’s marvellous to appreciate paintings, but why not have them? Why not create a whole aesthetic ambiente? Be your own living work of art?”

This sense of prodigious possibility proved a magnetic attraction for the Old World, and various transplanted representatives of the European aristocracy were soon vying with homegrown tycoons and scions to pay court to the kind of women that Capote would christen ‘swans’ for their formidable combination of looks, sophistication and the hauteur of the prodigiously long-necked. And if they didn’t necessarily mate for life, like their cygnine namesakes, they at least ensured that each successive marital arrangement was sufficiently advantageous. The Gilded Age, at the end of the 19th century, had occasioned the phenomenon of the ‘dollar princesses’ — daughters of the early American magnates and robber barons venturing to Europe to enjoin newly minted capital with venerable title; thus, the railroad heiress Consuelo Vanderbilt’s marriage to the Duke of Marlborough, or dry goods heiress Mary Leiter’s union with Lord Curzon. Now, it seemed, the traffic was all the other way. It wasn’t just that Pulitzer and her ilk — Babe Paley, say, or C.Z. Guest, or Slim Keith, Nan Kempner, Gloria Guinness, Lee Radziwill, Alice Topping, or Wendy Vanderbilt, a descendant of Consuelo — were superlative society chatelaines, presiding in Manhattan penthouses stuffed with post-impressionist canvases or Acapulco haciendas where they could pioneer the concept of ‘resort chic’, though they accomplished all that and more. “Style is what you are,” Capote liked to say, and these women’s ‘aesthetic ambiente’ was summed up by the title of one of photographer Slim Aarons’ compendiums: A Wonderful Time: An Intimate Portrait of the Good Life.

It was Aarons, above all others, who brought this American brand of the Belle Époque to life, with his photos of the monied at poolside play; he had taken the picture of Patsy Pulitzer on the seaplane, and other typical captions to Aarons’ studies might include: “A group of friends gather at the Richard Neutra-designed home of Palm Springs socialite and real estate expert Nelda Linsk (in yellow)” or “socialite Alice Topping reclines on a lounger with her lapdog” (though the latter photo caused something of a controversy, as people mistook Topping’s white bikini bottom for her underwear). As Aarons’ former assistant Laura Hawk made clear, in her introduction to the book Slim Aarons: Women, the photographer had his own, stripped-down aesthetic: “Upon arriving at his subject’s home, Slim first established a setting — an exquisite drawing room, a sun-drenched garden, or an allée of hundred-year-old walnut trees. The next decision was the subject’s clothing and appearance. Most often he photographed his subjects in the clothes they appeared in. He frowned upon women enhancing their hair or make-up, even for the dressier shots — he very much wanted his subjects to appear as they would in their everyday lives.” Aarons famously declared that he didn’t ‘do’ fashion: “I take pictures of people in their own clothes, and that becomes fashion.” Above all, Hawk said, “Slim favoured photographing women with great personal style and an abundance of confidence”.

Pulitzer caught a marlin weighing 1,230lbs, a world record for a woman, leaving Hemingway in her wake.

Aarons was once asked to name his favourite subject. “Babe Paley,” he replied. “She was the queen, gracious, utterly charming — what I thought every woman in America wanted to be.” If there was a hierarchy among the ladies who lunched at La Côte Basque or The Colony, and welcomed current or future presidents aboard their private jets, Babe occupied its most rarefied spot. “She was surely the most undishevelled person imaginable,” wrote George Plimpton, Capote’s biographer. “So groomed, everything perfectly in place whether she was sitting in a cabana on the lido or hosting a fancy dinner.”

Boston-born Babe was the daughter of the world-renowned brain surgeon Dr. Harvey Cushing, and her mother, Katharine, brought a similarly painstaking science to bear on finding her a suitably prestigious match. Babe hit pay dirt with her second marriage, to Bill Paley, the head of the CBS network: they became the tastemakers nonpareil of mid-century America, with Bill overseeing the production of everything from Gunsmoke to M*A*S*H, and Babe bringing what the society decorator Billy Baldwin called her “immaculate quality and immense serenity” to bear on punctilious hostessing, whether at the couple’s 820 Fifth Avenue apartment (where Picasso’s Rose Period masterpiece Boy Leading a Horse hung in the entrance hall) or their villa in Round Hill, Jamaica, where she’d be photographed by Aarons on the decking in her favoured china-blue pyjama suits (as well as lounge-luxe, Babe is credited with kickstarting the trend of mixing high-low pieces, and tying a scarf to one’s handbag).

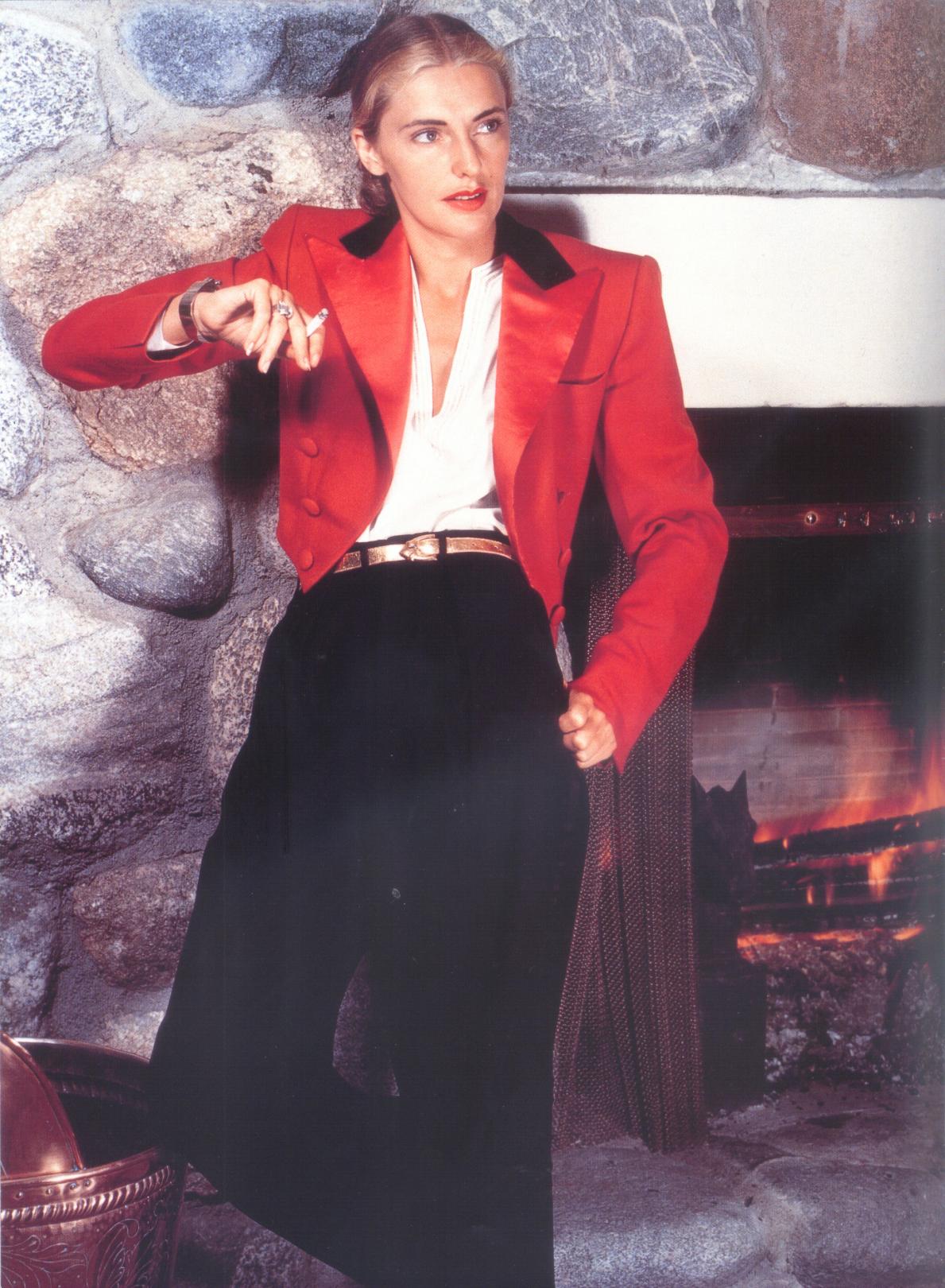

“Babe’s most endearing feature was that she was never full of herself,” reckoned Nan Kempner. “This wonderful sort of incompleteness was devastatingly attractive.” Kempner, along with Slim Keith and C.Z. Guest, brought a touch of salty American vernacular to the party, in contrast to the cut-glass Babe. Kempner had been born in San Francisco, the daughter of a Ford car dealer. An athletic American girlhood (“She looked great water-skiing on one ski, and she looked great on the slopes, too,” recalled a Lake Tahoe neighbour) and a taste for couture (she became a muse to Yves Saint Laurent, who called her “la plus chic du monde”) made her the ultimate clotheshorse, a title she exulted in, describing her style as “artificially relaxed — I’ve always liked being noticed, and I work hard at it”. She even put her own spin on the ‘lady who lunches’ paradigm: stopped at the door of a tony restaurant because she was wearing trousers (actually a Saint Laurent tunic over pants), she took off the bottom half on the spot, gave it to her husband, the investment banker Thomas Kempner, and, “flaunting the top as a minidress over racehorse legs”, as her Guardian obituary had it, “warily sat to dine”. (“I put a lot of napkins in my lap and didn’t dare bend over,” she said.)

The best-dressed woman in the world? That’s about as empty as ‘Miss Butterfat Week’ in Wisconsin.

Slim Keith was, according to Capote, “a lot of woman in every way”. She’d been born Nancy Gross in Salinas, California, but her golden looks and sylph-like frame proved the case against nominative determinism. “Apparently, the actor William Powell, who became a sort of father figure to her when she was a teenager, called her his ‘Slim Princess’, and it stuck,” Plimpton wrote. She was anointed the original ‘California girl’ and installed on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar by the time she was 22. Powell introduced her to Hollywood society, where her distinctly American vampiness and caustic irreverence (“Best-dressed woman in the world?” she opined, on being garlanded with the title in 1946; “that’s about as empty as ‘Miss Butterfat Week’ in Wisconsin. Let’s just say that I have a tall, skinny frame that simple, classic clothes look well on”) inspired Howard Hawks, her first husband, to imbue his leading ladies, notably Lauren Bacall, with similarly smoky, seductive qualities. Almost Hemingway-esque in her capacity to spin a good yarn while cradling a cocktail or two (Papa himself called her ‘Slimsky’), Slim went on to marry the theatrical impresario Leland Heyward, the producer of South Pacific and Gypsy, among others, and, finally, the British banker Kenneth Keith, aka Baron Keith of Castleacre; his family motto was veritas vincit — ‘truth conquers’ — but, now a bona fide Lady, it seemed that it was Slim who’d prevailed.

C.Z. Guest was photographed by Aarons at Villa Artemis in Palm Beach, her white shift dress and sun-bleached hair seemingly confirming her cultivated Hitchcock-blonde persona (Capote called her the ‘Cool Vanilla Lady’). In reality, however, C.Z. was as earthy as any couture-sheathed exemplar from a Boston Brahmin family could be. She was born Lucy Cochrane — her brother called her Sissy, and she adapted it to See Zee — and she came with the requisite appurtenances, from the 40-room family mansion to the equestrian menagerie; she went foxhunting with General Franco, and throughout her life, according to her friend Oscar de la Renta, the designer, “she assumed that everybody had a pony”. She rebelled against her debutante destiny, however, shocking the Mayflower matrons by staging a racy cabaret on the roof of the Boston Ritz, which led to a stint as a Broadway showgirl in the 1944 Ziegfeld Follies. Talent-scouted by Fox chief Darryl Zanuck, she never made it into a movie — though the gossip columns lapped up her trysts with, among others, Errol Flynn — and high-tailed it to Mexico, where she posed nude for Diego Rivera.

Rumour had it that when, in 1947, C.Z. married Winston Frederick Churchill Guest — cousin to the wartime prime minister, heir to a steel fortune, and champion polo player — the family spirited the portrait away from the Mexico City bar where it had proudly hung. The wedding was held in the Havana home of best man Ernest Hemingway — yes, him again — with whom Guest hunted big game. C.Z. now threw herself into running their expansive stables in Virginia, and perfected the jodhpur-clad, crisp-casual, clean-lined style that became the natural off-duty uniform of the private jet set. Even the Parisian houses she patronised — Mainbocher and Adolfo — were determinedly unfussy. “At heart she was this great beauty who had a tomboyish quality,” de la Renta said.

Gloria Guinness was the beneficiary of that most American of privileges — reinvention. She’d been born Gloria Rubio y Alatorre in Mexico in 1912, but her family had been ousted from their estates after the revolution, and Gloria now deployed her striking looks — angular features, huge brown eyes — to hustle her way into society. She kept details of her past deliberately vague — had she started out as a taxi dancer in Veracruz? Had she spied for the Nazis during the war? — but what was on the record was colourful enough. “She had married an Egyptian diplomat dispatched to Germany,” Plimpton wrote, “had danced with Goebbels in Berlin, married a Von Fürstenberg count, and eventually ended up with Loel Guinness, a banking scion and former M.P. and RAF pilot, who had residences in France, Palm Beach and Acapulco, as well as a large yacht named Seraphina.” Gloria, Plimpton went on, always reminded him of a flamenco dancer gone ‘cool’ — “a touch of Spanish in her accent, slim, vivacious, and always beautifully groomed. In New York, she was known as ‘The Ultimate’, and wore a ring so large she couldn’t fit a glove over it.”

It was rumoured at the time of the Guinness marriage that Loel had to purchase both the passport Gloria lacked and her dubious war dossier, but she preferred to address matters of style — “Elegance is in the brain as well as the body and soul,” she once averred, perhaps with one eye on the machinations that had facilitated her elevation — and housekeeping: she argued that it was easier to maintain multiple properties than a single one, as “you simply keep the appropriate clothes at the appropriate house”. At Gemini, the Guinness’s Palm Beach house, so-called because it faced the ocean on one side and Lake Worth on the other, Gloria would let her raven hair down. “She would put on the Chubby Checker records,” Plimpton wrote. “Everyone was doing the Twist then, and after dinner the younger guests would dance on the marble floors.”

It’s anti-Kardashians, a backlash against Photoshop and fillers. These women relied on an innate sense of style.

These exemplars of the new American royalty could even boast a genuine royal among their ranks. Lee Radziwill was dubbed ‘Princess Dear’ by Capote, thanks to her marriage, in 1959, to the Polish aristocrat Prince Stanislaw ‘Stas’ Albrecht Radziwill. The younger sister of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Lee may have failed to bag the equestrian trophies or top grades — or, indeed, a future president — but she was generally regarded by those who knew both siblings as having the edge in beauty and style, with a keener eye for fashion, colour and design; she was trim and dauntingly erect, with an imperious neck and high cheekbones, a three-highball- husky voice, and eyes that, as Capote rhapsodised, were “gold- brown, like a glass of brandy resting on a table in front of firelight”. A firm believer in Diana Vreeland’s remark that “elegance is refusal”, Lee, along with her contemporaries, embodied what were then the cardinal American virtues: a lack of flim-flammery and, alongside the dynamism, an instinctive discretion. As a New York Times appraisal following C.Z.’s death in 2003 affirmed: “It was an enchanting life, and what wasn’t so enchanting about it she had the good manners to keep to herself.”

That kind of constraint looks positively radical in the age of Instagram stories and oversharing influencers, and Aarons’ shots of l’heure bleue cocktails in the shadow of modernist dream homes and Moorish villas have, 50 years on, acquired a patina of almost Edenic innocence. Perhaps that’s why Babe, Nan, C.Z., Gloria, Patsy and the rest, and the idea of beauty they represented, still carry a powerful resonance. “It’s anti-Kardashians,” the art historian Tony Glenville told The Guardian, “a backlash against photoshop and fillers. These women relied on an innate sense of style, not surgery and Botox. And privacy is now a luxury, making them modern poster girls.” Poster girls, that is, for subtlety. For grace. For understated elegance. And for their spirited dedication to the very American art of the wonderful time.

Photo credits: Getty Images