LABEL OF LOVE

The genius of Atlantic Records co-founder Ahmet Ertegün lay in his ability to simultaneously shape and respond to the zeitgeist — musically, socially and sartorially.

In 1932, a nine-year-old boy from a devout Muslim family living in London — his father was a diplomat and legal adviser to Kemal Atatürk, founder of the Turkish republic — was taken by his elder brother, Nesuhi, to see the Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway orchestras at the Palladium theatre in London. “I’d never really seen black people except pictures of great artists like Josephine Baker,” the boy in question, Ahmet Ertegün, later said. “And I’d never heard anything as glorious as those beautiful musicians, wearing great white tails playing these incredibly gleaming horns with drums and rhythm sections unlike you ever heard on records.” The childhood epiphany sparked by this cultural ménage à trois would go on to change the course of popular music.

As teenagers, the family having moved to Washington, D.C., the brothers would comb black neighbourhoods for rare old recordings, and amassed a collection of some 25,000 jazz and blues records. Having earned a bachelor’s degree at St. John’s College in Annapolis, Ertegün studied medieval philosophy at Georgetown University, but his soul still danced to a groovier beat. “In between [classes], I spent hours in a rhythm and blues record shop in the black ghetto in Washington,” he said later. “Almost every night I went to the Howard theatre and to various jazz and blues clubs. I had to decide whether I would go into a scholastic life or go back to Turkey in the diplomatic service, or do something else. What I really loved was music, jazz, blues, and hanging out.” The pair had also been organising gigs at the Turkish embassy on Sunday afternoons.

It was not with his brother but his friend Herb Abramson that Ertegün co-founded Atlantic Records in 1947, initially operating out of an office in a derelict ground-floor office space in the Jefferson Hotel in Manhattan. Two record label launches had already failed, but this time Ertegün had financial wind in his sails, thanks to an investment of $10,000, borrowed from the family dentist. “I knew that the major companies were not making enough of the kind of records the black market demanded,” he said, and the likes of Big Joe Turner, Ruth Brown and LaVern Baker were among Atlantic’s early successes.

Harbouring a penchant for haute cuisine and the acquisition of Picasso paintings for his homes in New York City, Southampton, Paris and Bodrum, he dressed elegantly at all times. Esquire scribe George Frazier and Alan Flusser both celebrated his sartorial aptitude, which saw him plump sometimes for Ivy League insouciance — natural shouldered sack suits, button-downs, repp ties — and at other times for starched white shirts with French cuffs and gold links, a wooden cane for his troublesome hip only adding to the nobility of the elder Ertegün’s bearing. And there is plenty to suggest he was as elegant inside as out, not least Atlantic’s reputation for financial fair play with its artists: he reputedly encouraged the Stones to swap labels in the mid 1980s because they could get more money elsewhere, and in his later years strived to recompense some of the black R&B artists who had fallen victim to pitiful royalty payments, including Atlantic’s donation of $1.5 million to the Rhythm & Blues Foundation.

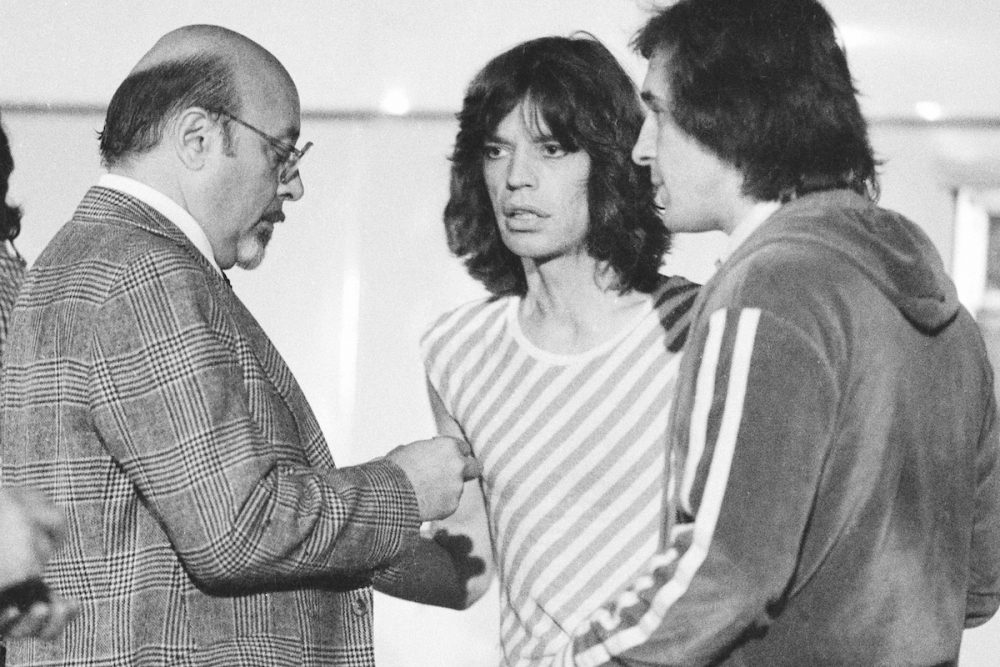

A gregarious social whirlwind, he was as content at a gritty music venue as he was hobnobbing with haute society, often mixing the two. (“I must have met him on Led Zeppelin’s first U.S. tour,” Robert Plant has remarked. “Ahmet was always backstage with an entourage of folk, this melange of people from all walks of life. He’d have Henry Kissinger or a princess from some deposed royal family from Eastern Europe.”) According to Robert Greenfield’s book The Last Sultan: The Life and Times of Ahmet Ertegun, the shindig he threw on the Starlight Roof of the St. Regis hotel in Midtown for Mick Jagger’s 29th birthday and the end of the Stones’ 1972 tour trumped Capote’s famous Black and White Ball as ‘bash of the century’. “For the first time in America, high society came to see the Rolling Stones,” Greenfield wrote.

Ertegün had a mischievous sense of humour — while wooing his then-already-married wife-to-be Mica, he’d hide a small orchestra in the bathroom of her suite at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Montreal, and ask them to play Puttin’ On the Ritz as she entered the room — and, to borrow an obituary euphemism, was ‘sociable and affable, no matter the hour’. “I used to drink a bottle of vodka a day, every day, for about 40 years, and it never occurred to me it’d kill me,” he once said. “My doctor said I should stick to wine.” It’s a quote that won’t surprise former Atlantic artist Tori Amos, who once told Vanity Fair: “Labels and artists are never going to get along, because they think we’re brats and we think they just haven’t smoked enough. But with Ahmet you know he’s smoked more than you ever did. I don’t know what he’s got in his tea, but he can dance your butt off the floor. I can’t keep up with him. He just puts me under the table.”

And yet, so steady a hand was Ertegün’s on the tiller, Atlantic weathered, over the decades, complex ownership permutations worthy of the modern car industry. It was sold to Warner Bros.-Seven Arts in 1968 for $17 million (some of which was used to found the New York Cosmos soccer team), which itself was acquired by Kinney National Services, which became Warner Communications, which became Time Warner. It would later survive another bout of mergers and acquisitions in the 1990s, and Ertegün was still serving as Chairman of Atlantic when, in December 2006, he died in Manhattan aged 83 of a brain injury suffered during a fall at the Beacon theatre as the Rolling Stones prepared to play Bill Clinton’s 60th birthday concert. Such is his legacy that the main exhibition hall at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland — an establishment he helped to found — is these days named after Ertegün

The reason the nine-year-old Ahmet Ertegün had never heard the percussive exuberance of big-band jazz until he saw Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway that night was that, at the time, rhythm sections were recorded softly to protect the delicate grooves of 78rpm records. It’s fair to say that this is a man who did more than anyone to give popular music a more robust groove. The word ‘humility’, meanwhile, is a pretty blunt stylus when it comes to decoding one particular statement of his, made shortly before he died: “I’d be happy if people said I did a little bit to raise the dignity and recognition of the greatness of African-American music.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 57 of The Rake.