Pandit Country

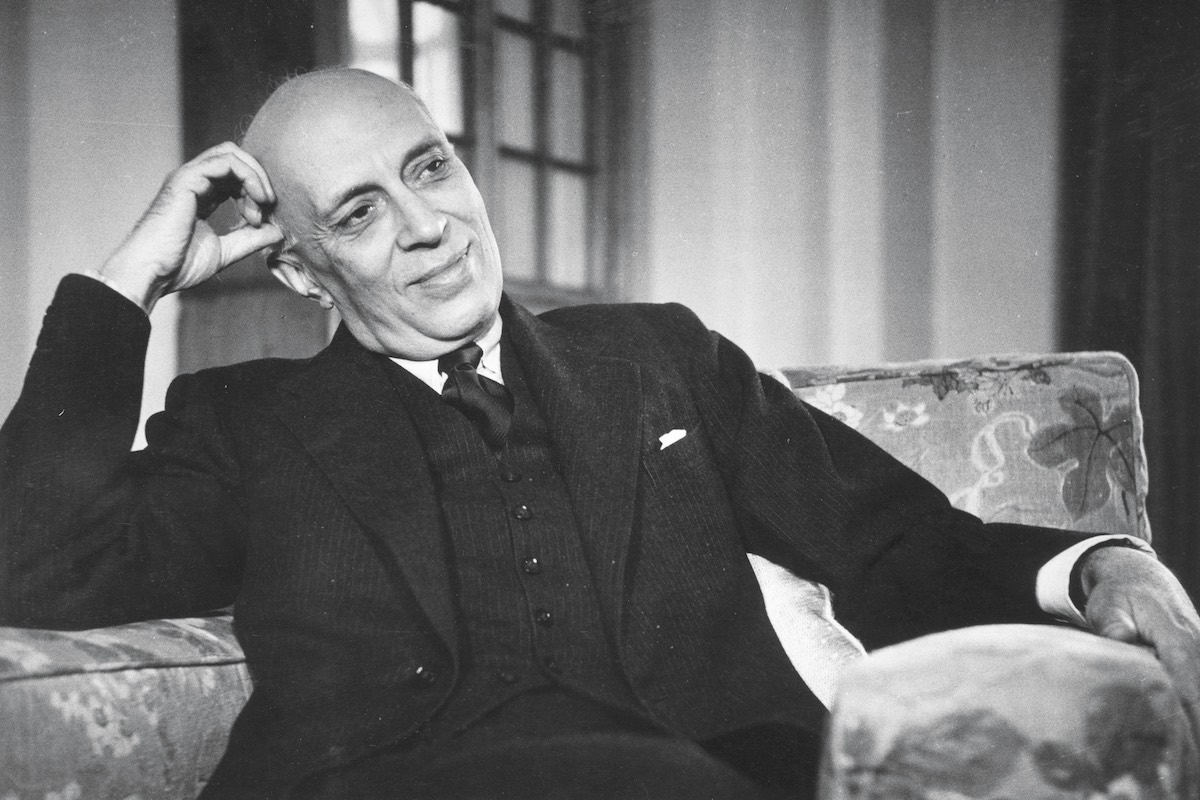

Modern India was forged by one man: Jawaharlal Nehru. The irony, of course, is that Nehru was forged by the very British system he sought to eclipse. Now, 55 years after his death, Pandit’s legacy still looms large over the world’s most populous democracy.

In the summer of 1945, the crème de la crème of Indian politics gathered in the small city of Simla, in the hills of northern India. For almost 100 years, Simla had been the summer capital of British India, where annually the entire machine of government decamped from sweltering Calcutta and later Delhi to the cool and picturesque hill station. In 1945, that period of India’s history was coming to an end as Britain prepared to grant its imperial jewel independence, and Simla was where it would be hammered out.

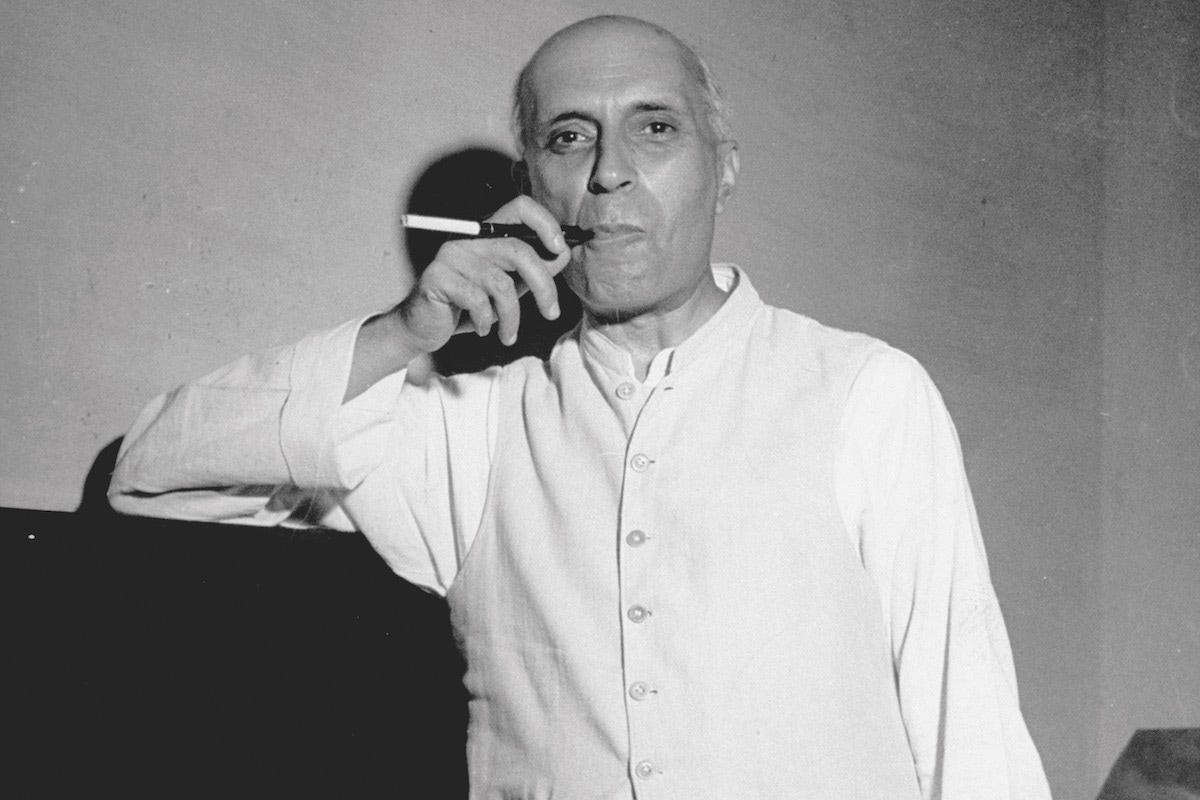

Delegates arrived from across the country, many in carriages or rickshaws pulled by men up the steep drive to the Scottish baronial style Viceregal Lodge, the summer home of the Viceroy of India. But one arrival drew everyone’s attention. Riding a piebald horse and wearing his trademark achkan and cap was Jawaharlal ‘Pandit’ Nehru, president of the Indian National Congress that had fought for decades to secure the colony’s independence. The entrance stopped the press and other attendees in their tracks, and was typical of the man who would become his country’s first prime minister, serving in the role from 1947 to 1964. His Congress Party ran India almost uninterrupted from independence until 2014.

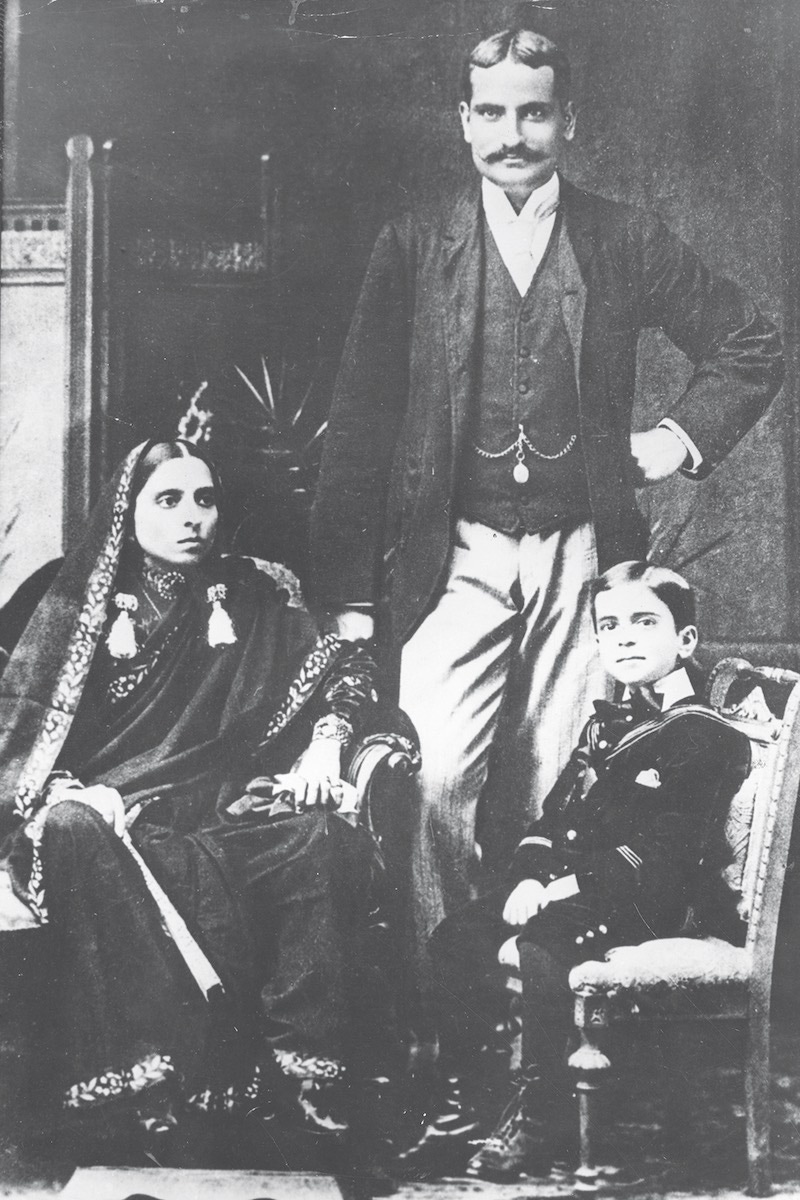

Born in 1889 to a wealthy family in central India, Nehru led a gilded existence in British India. His father sent him to Harrow, which he followed with a natural science degree at Cambridge and law studies at Inner Temple. He was called to the bar in 1912 and returned to India. The Nehru family hoped their son would prosper as a lawyer in their home city of Allahabad, but he had been an Indian nationalist since childhood, and, as an adult, it took up almost all his time. In 1916 he married Kamala Kaul, a fellow freedom fighter, but even she was often overlooked during the struggle for independence. The pair had two children, a son and a daughter, Indira, but their son lived only for a week.

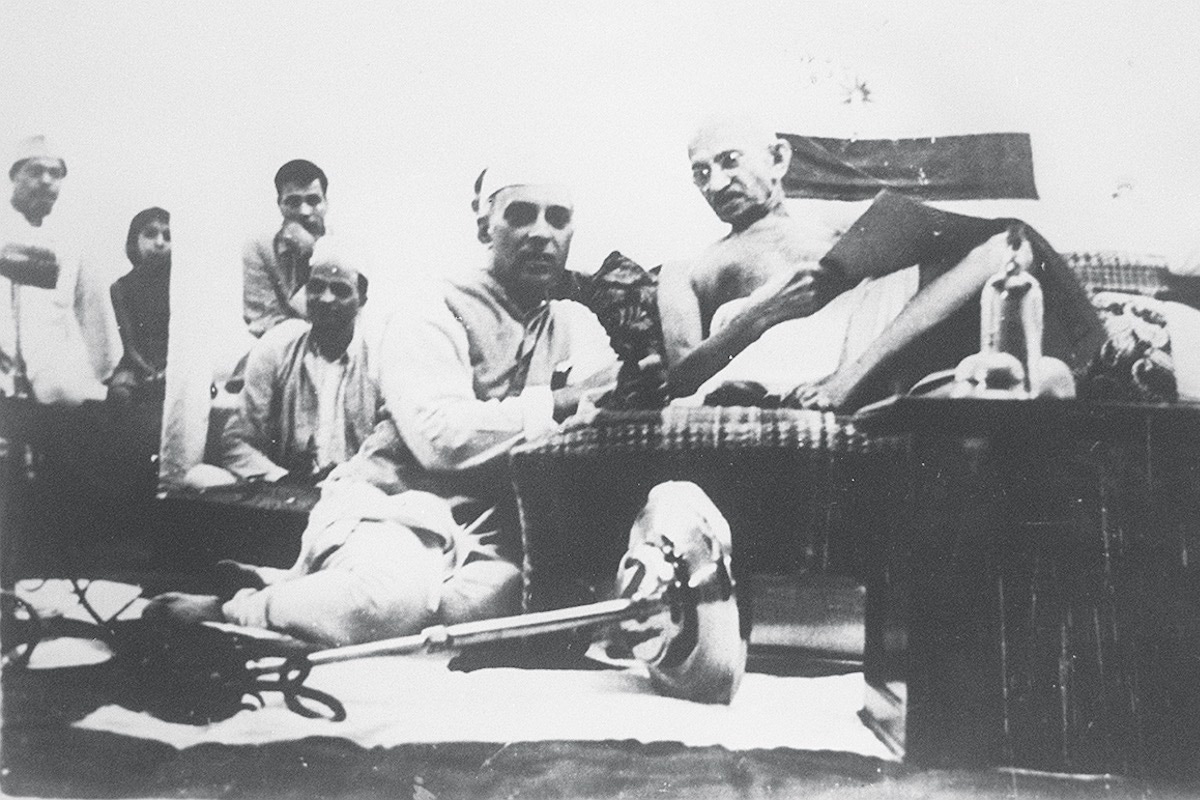

Nehru’s father, Motilal, was another key independence activist, having served twice as president of the Indian National Congress, inspiring a young Jawaharlal. In the following years Jawaharlal echoed and then eclipsed his own father. Rising up the ranks and building friendships with fellow freedom fighters like Mohandas Gandhi, Nehru eventually found himself at the head of his party in 1929 and leading the call for Indian independence. His work in that position culminated in the meeting in Simla and the realisation that Britain really would ‘Quit India.’

For almost 200 years, the British crown had ruled the subcontinent and the hundreds of millions who lived on it. It had previously come under the control of the East India Company, but after the Indian Mutiny in 1857, the British government decided to take direct control of one of the most profitable parts of its empire. While comparably less strict than other colonial powers, Britain exerted total control over India and its subjects. Working with native princes, a force of under 1,000 civil servants were able to administer an area 20 times larger than Britain. At the end of the 19th century, when the empire reached its peak, intellectuals like Nehru’s father, and later his son, realised they could be masters of their own destiny. By exposing them to the academic thought and freedom of Europe, and encouraging assimilation, Britain had created an Indian ruling class numbering many families like the Nehrus who saw no reason why they should help run a foreign country’s colony.

Nehru was, like many other members of the Indian elite, incredibly westernised. They spoke English as their first language, went to Oxbridge and then the Inns of Court, and sent their children to British public schools, even going so far as to put the independence struggle on hold to help Britain fight Hitler and the Japanese during the second world war. Even today, Nehru’s descendants and other high society Indians use English between themselves, often reserving Hindi for interactions with staff.

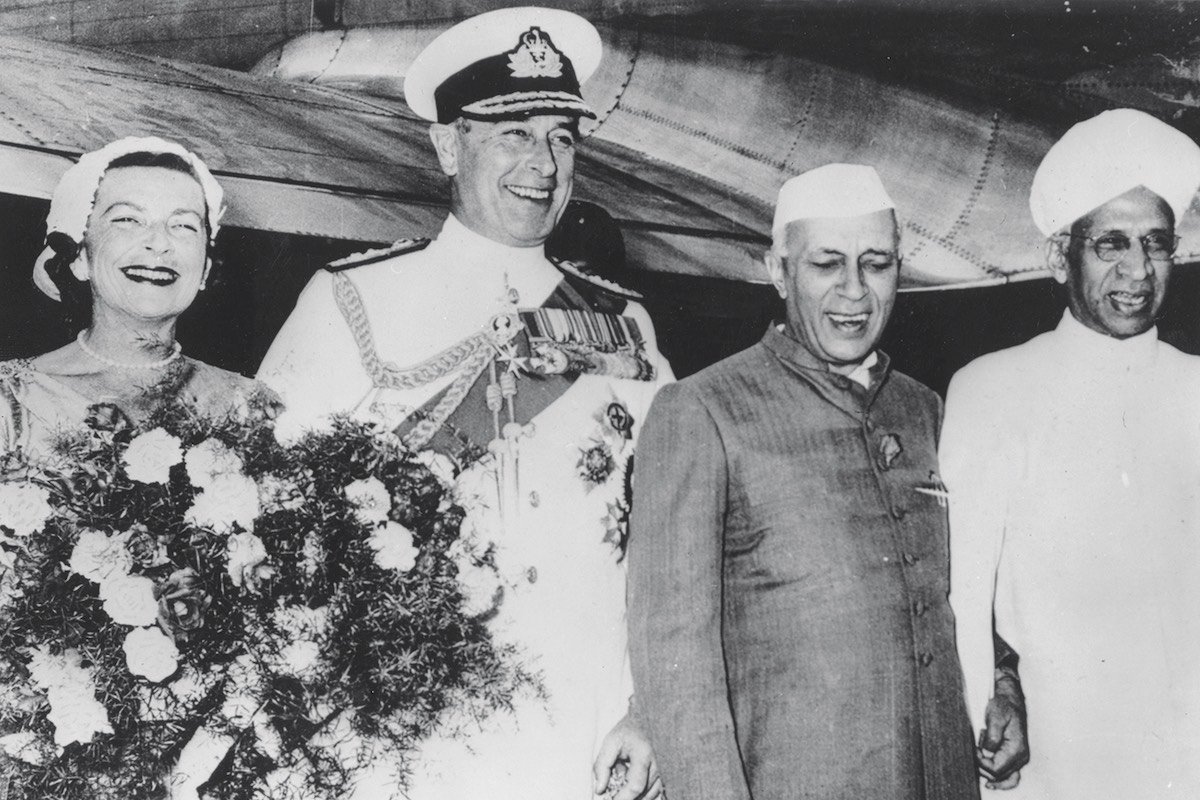

In 1947, less than two years after the meeting in Simla, the final Viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten, ordered the hauling down of the Union flag at Viceroy’s House in Delhi and the handover of administration to two new independent nations: India and Pakistan. Nehru became the prime minister of the former. Despite most of the eyes at the flag ceremony focusing on the long-awaited creation of a new country, some less interested pairs observed one of the most famous open secrets in India: the Mountbatten-Nehru love triangle.

Almost as soon as the Mountbattens had landed in Delhi to take over their ceremonial posts as Viceroy and Vicereine, rumours circulated that Lord (Louis) Mountbatten’s wife, Edwina, had become romantically involved with Nehru. Photos from events often showed them sharing asides and jokes while ignoring the Viceroy. Nehru’s wife, Kamala, had died from illness in 1936, and the idea the Vicereine would conduct an affair, especially with an Indian, scandalised the British in India and back home. While the Mountbattens were known to have, by their own admission, barely shared a bed during their marriage, there is no evidence the relationship between Nehru and Lady Mountbatten was anything more than platonic. The Mountbattens’ daughter Lady Pamela Hicks makes the point that people in their positions would simply not have had the time to lead a romantic affair, let alone the privacy to do so. Instead, Hicks says it was simply a “profound relationship” based on the “equality of spirit and intellect” in which Nehru provided Lady Mountbatten with the companionship “she craved”. When Edwina died, Nehru sent a ship from the Indian Navy to follow as her ashes were scattered at sea and throw a wreath from him where they fell.

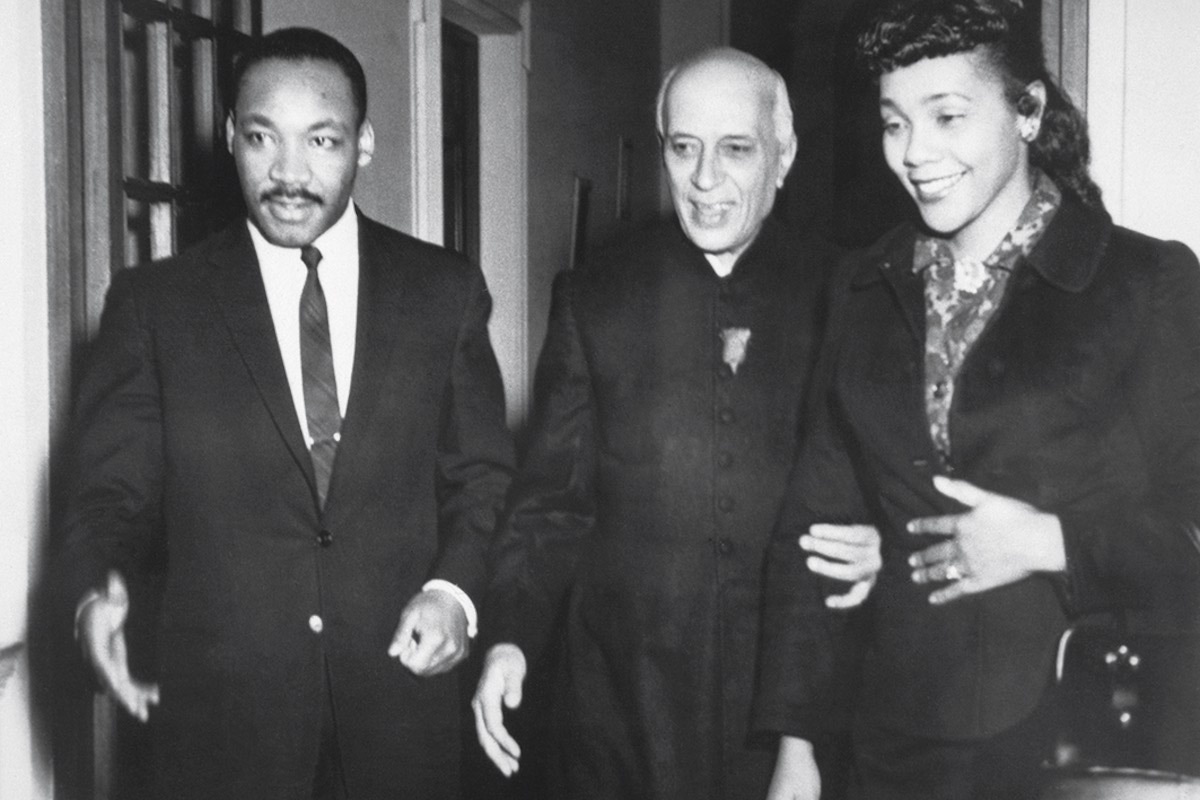

After the Mountbattens and the rest of the British had left, Nehru was left to run India on his own, and to shape it in his image. He took over a country that was incredibly poor, with astonishingly low levels of literacy and severely lacking food. His dream of a free India was a completely secular and socialist nation, having become acquainted with Karl Marx and other left-wing philosophers at Cambridge University. He regarded himself as a Hindu agnostic, who saw dogmatic religion as one of the most dangerous things for a society. Discarding the Indian issue of caste, Nehru believed people should simply “develop along the lines of their own genius”. He focused on the development of young people, giving even the most rural Indian child a primary education. He became known throughout the country by children as ‘Uncle Nehru’. Children abroad would often write to Nehru, and he would sometimes reply by sending an elephant to their local zoo as a gift, boosting knowledge of India through what was then known as ‘Elephant Diplomacy’.

Another elephant of Nehru’s premiership was the issue of partition. Years before, he had refused to stop the split of India along artificial religious lines by the British. On India’s western and eastern borders would be Pakistan, a Muslim homeland with Eastern Pakistan eventually becoming Bangladesh. Millions died in the chaos of partition, as religions fled their respective countries to where the British civil servants in London decided they should live. In the long term, religious divides still haunt India, and the two countries, once brothers, are now mortal enemies. A system of religious accommodation that had been built over more than a millennium had been shattered in months, and it remains one of the ugliest legacies of the British Empire — something many argue Nehru could have stopped or at least mitigated.

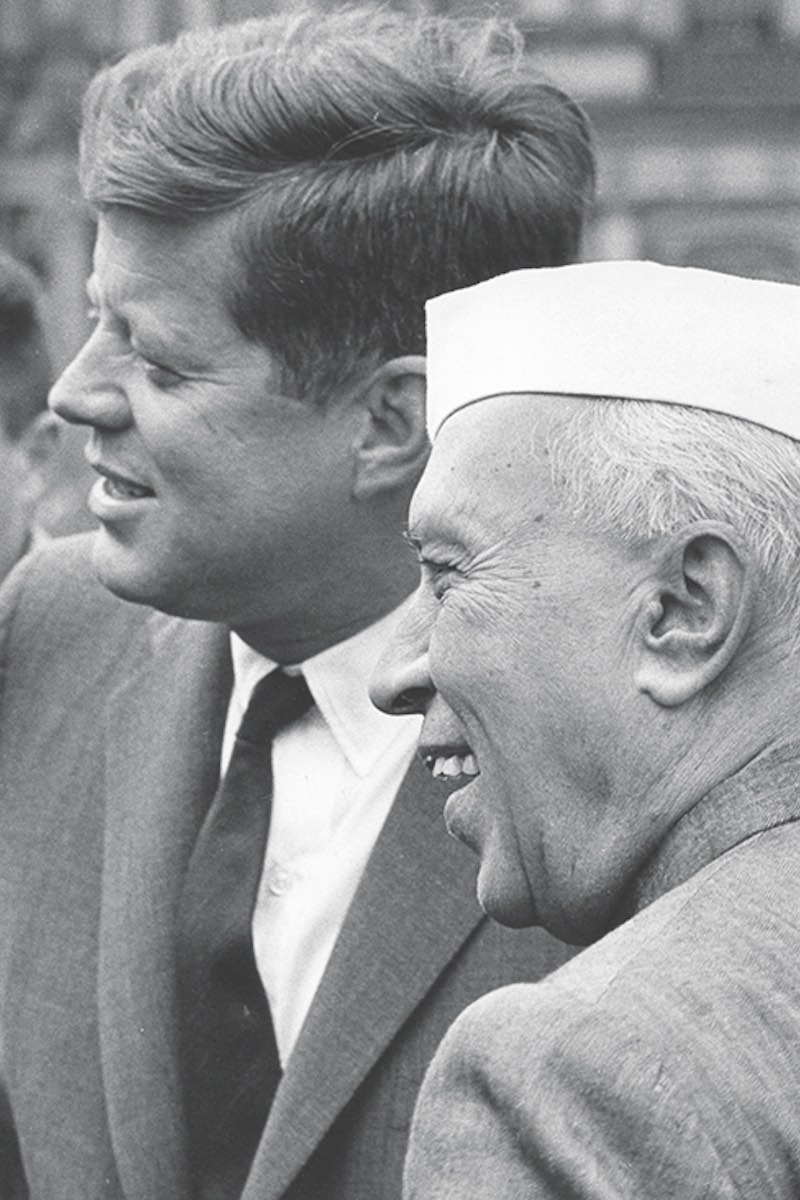

Much of his timidity came from his personal nature, of being quite thin-skinned. A secret file of the British India Office claimed that Nehru “gave the impression he would not stand up well to anything in the nature of serious heckling”. When criticised by his colleagues, they would feel his wrath, and he went out of his way to make foreign leaders happy.

Running the country allowed him to create a vast system of patronage in which his Congress made politicians reliant on the party, ensuring loyalty and control that long outlasted him. A minister once said that the prime minister “was like a great banyan tree. Thousands shelter beneath it but nothing grows.”

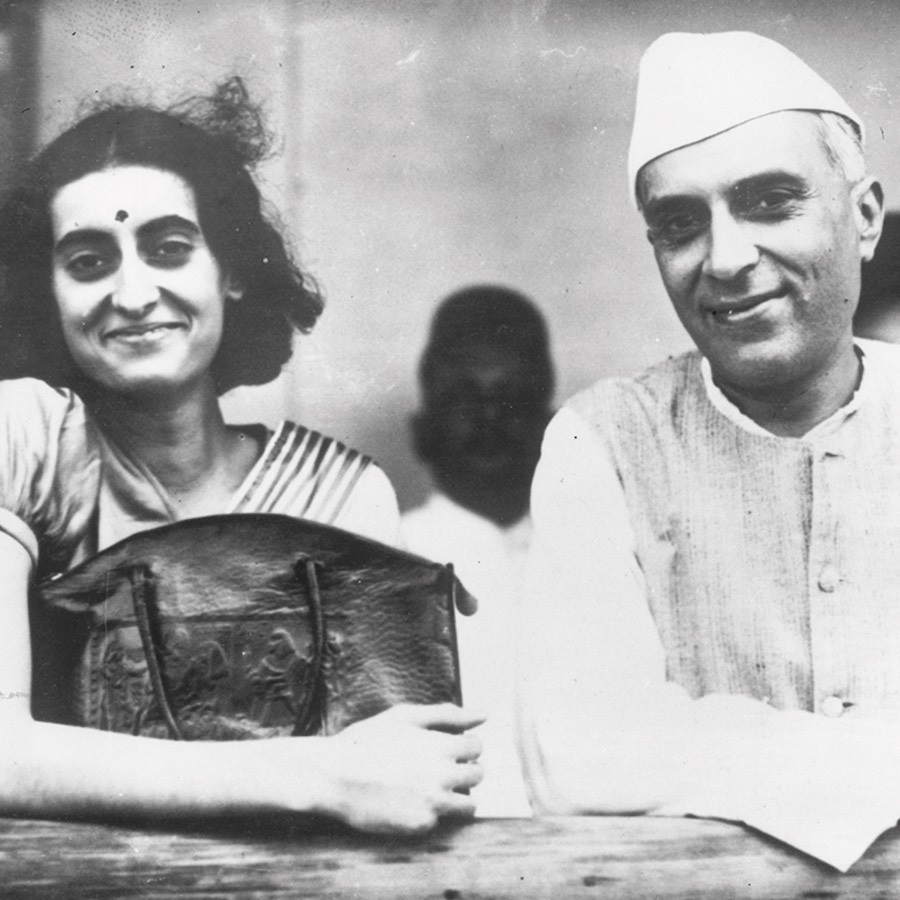

While Nehru had thrown off a hereditary monarchy and integrated the various Maharajas and other Indian potentates into his model republic, he groomed his only surviving child, Indira, to succeed him. Just as striking as her father, Indira had a streak of grey hair that was complemented by her trademark outfit of colourful handwoven sarees. She also married another politician, Feroze Gandhi, and they had two sons. As Indira built up her image and profile, her father suffered from poor health in the early 1960s following a disastrous war with the Chinese over border issues, and he died from a heart attack in 1964. Nehru’s death, at the age of 74, was announced to the country with the words, “The light is out”, echoing the aftermath of his friend Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination in 1948.

Indira had served her father as his de facto private secretary for much of his time in office. Two years after his death she became prime minister herself. There was no other possible heir, as Nehru had ensured no one outshone him on the political stage.

Indira served for 11 years before being forced out of power over a tyrannical state of emergency she instituted between 1975 and 1977. After a brief spell in jail she was re-elected in 1980. She ruled until 1984, when she was assassinated by her own Sikh bodyguards in retaliation for ordering military action in the holy Sikh Golden Temple to resolve a hostage situation. She was succeeded by her son Rajiv, who served as prime minister until 1989. Between independence and 1989, there were only six years in which India was not controlled by Nehru or his descendants. Today, his descendants still occupy prime positions in Indian politics and still run the Congress Party, which has been out of office since 2014 after losing to the current prime minister, Narendra Modi.

While Nehru remains a colossal figure in India, where his legacy looms over society, he is mostly forgotten by the wider world. The most likely way his name is heard in London today is when discussing the ‘Nehru jacket’, a simple hip-length button-down tunic with a mandarin collar. They are most often seen at parties where men try to be different by not wearing ordinary black tie, hoping instead to emulate one of the most elegant politicians in history, though incredibly the eponymous jacket was a garment Nehru never wore. He would instead always be seen in a perfectly tailored achkan, as he wore astride his horse to go to Simla in 1945.