Sid Vicious: The Grubby Demon of Punk

He was an icon of freedom and a helpless addict, rock ’n’ roll inspiration and cautionary tale. Simon John Ritchie — a.k.a Sid Vicious — just couldn’t escape his own contradictions. He was dead at 21.

It’s easy to hate Sid Vicious. He is, after all, to blame for embodying one of the 20th century’s most exciting art movements in the form of a drooling, talentless junkie in a swastika T-shirt.

Beyond the ferret-faced, sneery urchin cartoon, though, there’s another Sid, not much more real but closer to something celebratory, romantic and even meaningful. Like the Marquis de Sade or Francis Bacon or Quentin Tarantino, he took ugliness and nihilism to their extremes, and found beauty in them. He said it best in an interview filmed in December 1978, close to the end of his brutishly short life. “What would you like to happen over the next year or so?” asks the interviewer, to which Vicious replies, “I’d like to have fun… That’s my object in life.” Its glorious simplicity, ludicrously, stops you short: what else is there, after all?

The trouble is that life isn’t that simple, as Sid had already found out. “Are you having fun at the minute?” the interviewer continues. “Are you kidding?” he replies, his voice telling a world of pain and bewilderment. “I’m not having fun at all.” That’s Sid: icon of freedom and helpless addict, rock ’n’ roll inspiration and cautionary tale: he’s both sides of the same argument.

For an icon of anarchy, his start was stock-joke Little England. Born in the conservative heartland of Tunbridge Wells in peak post-war-grey 1957, he was named with near-comic blandness Simon John. Originally his last name was Ritchie, though he often went by his mother Anne’s surname, Beverley. An early adoptee of the bohemian lifestyle and a heroin addict herself, she remained a presence in his life until his death, but rarely a positive one. She threw him out of the house at 17, telling him, as she recalled to the writer Jon Savage, “It’s either you or me, and it’s not going to be me. I have got to preserve myself and you can just fuck off.”

Sid found a place in a squat with John Lydon (not yet Johnny Rotten), whom he knew from further education college. Along with John Wardle, later to become Jah Wobble and a co-founder of Lydon’s post-Sex Pistols band PiL, they sought out the clubs and assembly points of what would become punk, including Sex, the King’s Road boutique run by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren. Sid was unworldly and easily led, looking for somewhere to belong. Viv Albertine, of The Slits, remembered him as “kind of sweet”, and Lydon, sensitive and clever as well as angry, saw this too, giving his man-child friend his nickname not because he was violent but because he wasn’t: Vicious was the name of Lydon’s hamster.

Punk was about wildness, not vulnerability, however, and Sid had this as well. When Lydon became Sex Pistols singer Johnny Rotten, punk’s figurehead, Sid came along, there at every one of the defining early moments, even credited with inventing the pogo, punk’s own dance move. He embraced the movement’s nihilism. He attacked the journalist Nick Kent with a bike chain — Kent was a punk cheerleader and almost a member of the Sex Pistols himself. And at the tiny Punk Rock festival of September 1976, Sid threw a glass at the stage that shattered and half-blinded a 17-year-old girl. For this he spent a week in a remand centre in Kent with just a biography of Charles Manson as company, an experience that seemed to harden his resolve to pursue only his own gratification, or “total personal freedom”, as he put it.

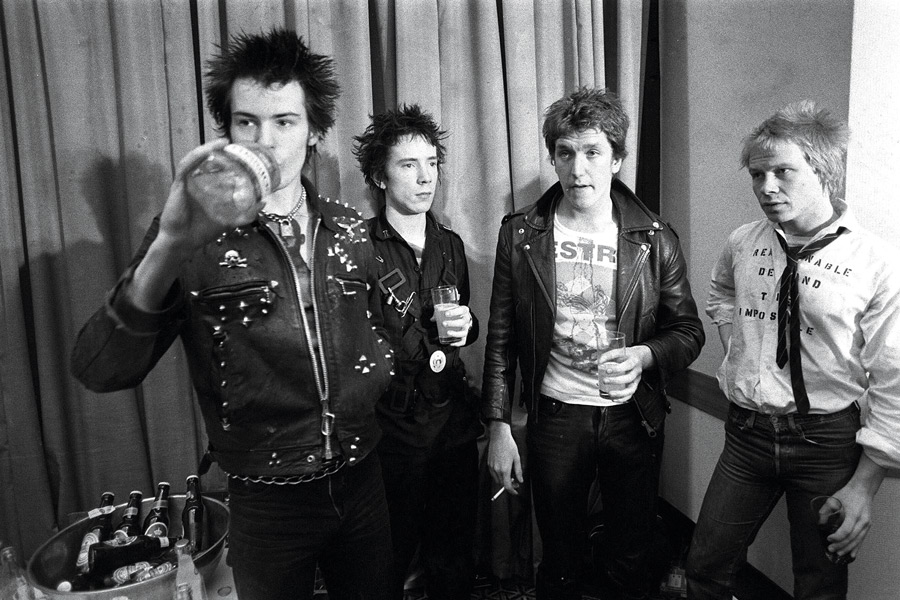

To Britain at large, still a land of pale ale and cub scouts, Sid was just another juvenile delinquent. In the foreign country of youth culture he was a star. Within six months he was installed as bassist with the Sex Pistols, deposing Glen Matlock, who had written the band’s songs but looked unacceptably tame. Whether Sid could actually play is still debated, but it didn’t seem to bother him unduly. “I don’t understand why people think it’s so difficult to learn to play guitar,” he told one journalist. “I found it incredibly easy. You just pick a chord, go twang, and you’ve got music.”

In all other ways, he was perfect. As Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones recalled in 2008: “I saw Sid walking down the King’s Road way before the Pistols, and thought, ‘Wow, that guy looks cool’.” On paper, this look was almost absurdly basic: a T-shirt or bare chest under a leather jacket, a padlock on a chain as a necklace, jeans and biker boots, and a sneer. His hair, which quickly became the prime signifier of punk rock, still copied by Los Angeles teenagers 40 years on, was simply a spike cut unwashed and slept on. Whatever he touched became punk rock. Coupled with his air of childlike vacuousness and vague menace, jelly shoes, a tennis wristband or a plain grey raincoat were fashion, even a statement, like his badge that told the world, ‘I’m a mess’.

There was also his commitment to the punk cause. From the start he proved himself good for a provocative press quote. Whatever it was, he was against it. “I’ve got absolutely no interest in pleasing the general public at all,” he told one reporter. “I don’t want to because I think that largely they’re scum and they make me physically sick.” For a time he was focused on the job, too. Paul Cook, the Sex Pistols’ drummer, remembers the first few months of Sid’s tenure as the band’s best period: “He was really determined to learn the bass and fit in and be part of the band.” This changed with the arrival of Nancy Spungen, onetime stripper, part-time prostitute and full-time hanger-on. They were drawn to each other by shared trauma and need. Everyone else loathed her. “In a few weeks, Sid went to being the worst kind of rock ’n’ roll idiot you could ever have a nightmare about,” Lydon ranted in Julien Temple’s 2000 documentary The Filth & The Fury. “We tried our best to get rid of Nancy. One night, I even dangled her out of a window by her heels. But it was no use.”

Sid, no stranger to hard drugs, became a junkie, encouraged by Nancy and fascinated by the example of his heroes, Iggy Pop and Dee Dee Ramone. Rather than follow his own instincts, he became a cartoon version of their already cartoonish personae, ignoring the creativity that lay behind them. Soon, he was calling out the rest of the Sex Pistols for not being punk enough. “All three of them are real straights, in a way,” he told one journalist. “I can’t stand their lifestyle. Sitting around bars drinking beer, getting fat and screwing the occasional whore. Disgusting, it is.”

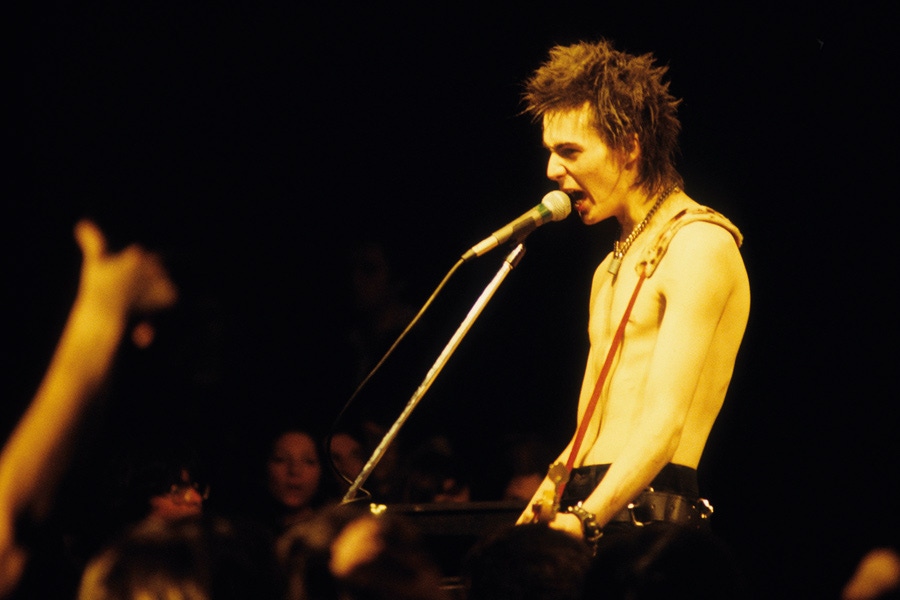

He craved attention but couldn’t handle it, as proved on the band’s dismal U.S. tour of January 1978, when he screamed abuse at the audience and regularly took to the stage with open wounds cut with a broken bottle. It was in this pose that he was immortalised on film at the Sex Pistols’ final show, in San Francisco. Mouth half-open, his legs splayed and his Fender bass held low and wide, he is both ghastly and superb, a grubby demon from a Victorian tale of moral improvement but also the essence of punk’s mission to break taboos and, beyond that, of visionary French poet Arthur Rimbaud’s “derangement of all the senses”.

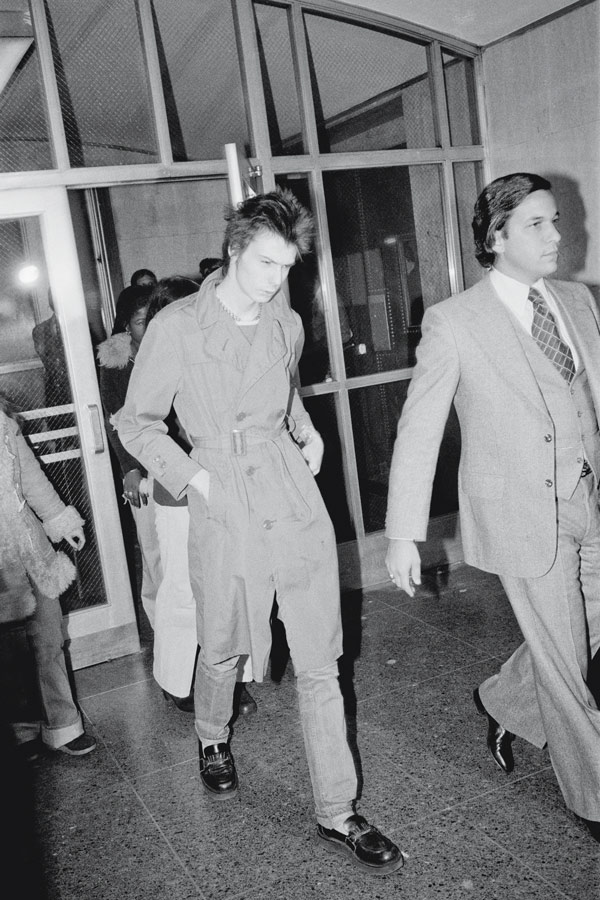

Whatever the significance of the moment, he was out of his depth and fell fast. Long before the implosion of the Sex Pistols, Sid had shown himself capable of violence, both towards hotel rooms and Nancy. Heroin had become his priority, and he began overdosing on a regular basis, starting with the last night of that American tour. He told anyone who asked that addiction was going to kill him, sometimes with bravura but increasingly with helplessness. When he was arrested in October on suspicion of murdering Nancy in New York’s Chelsea Hotel, all hope withered and died. With hindsight, no other end to the story seems possible. He was bailed, rearrested, imprisoned, hospitalised. Released after two months, he overdosed the next day, on 2 February 1979.

It could have been different. “He would have been a great frontman, Sid,” maintained Steve Jones. “He could sing and he had a lot of stage presence.” After the Sex Pistols he had played a few New York shows backed by various punk allstars; he was a state, but a charismatic one. The final Sex Pistols singles with Sid on vocals, versions of old rock ’n’ roll standards, were the band’s biggest sellers. His own cover of My Way was, against all odds, magnificent. Even Leonard Cohen, interviewed in 1998, declared his admiration for it. “The certainty, the self-congratulation, the daily heroism of Sinatra’s version is completely exploded by this desperate, mad, humorous voice,” he said. “It takes in everybody; everybody is messed up like that, everybody is the mad hero of his own drama.” Vicious was a mess. Maybe that’s why, beyond the cartoon with the sneer and the spiky hair, it’s so easy to love Sid.